9 The Industrial Shingwauk Home (1874-1935)

Engacia De Jesus Matias Archives and Special Collections, Diocesan Heritage Centre photograph collection, 2013-077/008(011).

Life at the Shingwauk Home: an Indian Residential School

What began as a scattering of modest buildings on 90.5 acres of land acquired in 1874 for ‘Indian Education’ became an ever-expanding industrial school complex and home to hundreds of Indigenous children. Toward the 1930s, the various trades and infrastructure that had supported industrial education were dismantled in favour of a new program of austere and rudimentary formal education – the Residential School System. This gallery is dedicated to lives lived at Shingwauk and offers a glimpse of the day-to-day existence of children over the 100 years of the schools’ operation.

Before the Indian Residential School

Indigenous children didn’t arrive at the Residential School as blank slates. Rather, they brought with them a wealth of early childhood, familial, and cultural experiences, which varied depending on the era and their personal circumstances. Upon arrival, the children found their sense of self and community immediately under assault. While Christian names, school uniforms, and haircuts robbed them of their individuality, the more insidious work of eroding and replacing their cultural values and identities – ‘killing the Indian in the child’ – began as they became inmates of the institution.

The Industrial School Era – Shingwauk Home 1875-1934

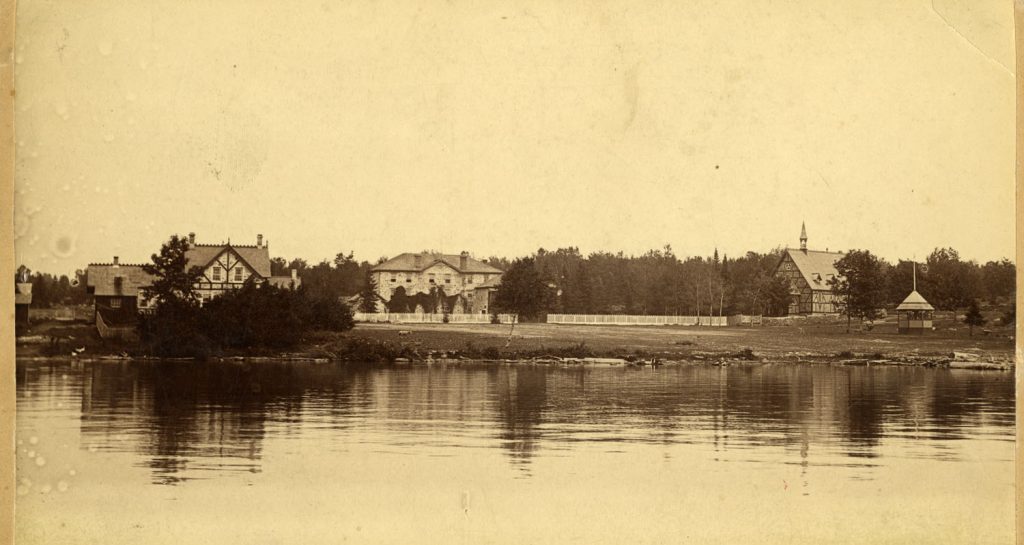

Following an unsuccessful attempt to establish a more modest Shingwauk Home on the Garden River First Nation, founding principal Reverend Edward F. Wilson acquired the current site, transforming it into an industrial campus. Over the 59 years that correspond with the Industrial School Era, these grounds witnessed many enterprises, industries, and programs. The main building, Shingwauk Home, was successively expanded and contained student and staff quarters for sleeping and eating, as well as kitchens, offices, and classrooms. A working farm complete with livestock, dairy, storehouse, barn, and stable, a hospital, the principal’s family residence, and a chapel with cemetery occupied the grounds, along with the many outbuildings where vocational skills such as carpentry, printing, tailoring, shoemaking, and weaving were taught. Across the site were places of punishment, but also secret places of refuge created by the children. Although originally intended to house both girls and boys, religious and social mores of the late 19th century compelled their segregation.

Following the departure of the Reverend Edward F. Wilson, the Shingwauk School struggled to maintain adequate funding. Community connections were severed and the school gradually became absorbed into the Canada-wide Indian Residential School System. By the 1930s, the Shingwauk Home had become dilapidated and a new modern building was considered necessary.

The Reverend Charles F. Hives, who became the principal in 1926, found the Shingwauk Home “ill planned, unsanitary, in very dilapidated condition,” further declaring:

“I’ll never forget the multitude of rats that appeared to inhabit the old building. Surely Hamlin town had no greater need of a Pied Piper than did old Shingwauk in those days.”[1]

[1] Charles. F. Hives, “The Period of Transition: A Short Sketch by C. Hives, Principal 1929-41,” Algoma Missionary News: Shingwauk Indian Residential School Special Supplement, 1944, p. 321.