8 Indigenous Clothing

Indigenous clothing and hair can hold a great amount of meaning for the people who wear it and the people who see it. It can be used to reflect social order, gender, age, marital status, family affiliation, and much more (McCord Museum, 2013). For many students going to Residential School, their clothing and hairstyle would have been an important connection to their home communities and families, and a marker of their individuality. Therefore it was a prime target for assimilationist tactics. Ben Barry, an associate professor of equity, diversity, and inclusion at the Ryerson Fashion School, states that “fashion is obviously a field that perpetuates colonialism against Canadian Indigenous people” (McKay, 2016). When children came to Residential Schools, their handmade clothing was often discarded, and survivors speak of it being ridiculed and burned (Truth and Reconciliation Commission, 2015). They were made to wear westernized clothing which was often an identical uniform and could be poor in quality and not proper for weather conditions. Childrens’ hair was often cut into identical styles, further stripping them of a connection to their culture and individuality.

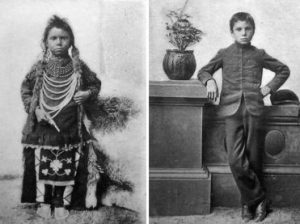

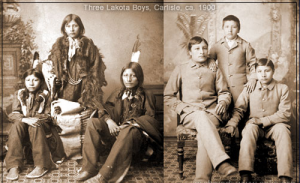

Clothing was often used as a way to show the progress of the student and the benefits of the school in “civilizing” Indigenous people. Before and after photos are common throughout Residential School history and sometimes show a mish-mash of clothing from multiple different cultures, rather than an accurate representation. Indigenous clothing was widely mocked by the settler community and seen as a sign of savagery. Later, it was greatly misappropriated and treated as a costume devoid of meaning.

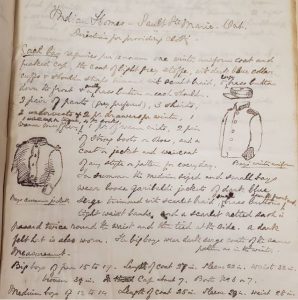

At Shingwauk, students were expected to wear European clothing. Most of this clothing was donated by patrons of the school, or paid for by their monetary donations. When supporting a student, a Sunday School or individual could either pay $75 a year and have Principal Rev. E. F. Wilson purchase the clothing, or they could pay $50 and send 1 coat, 2 suits of clothes, 3 shirts, 4 pairs of socks, 2 caps (1 winter 1 summer), 1 pair of boots, 1 muffler, 1 pair of mitts, 2 pairs of winter drawers, 2 undervests, and 4 pocket handkerchiefs. These could be gently used or handmade by donors such as the various different Ladies Sewing Societies. These expected clothing donations, as well as the monetary donations, often fell far short of the needs of the school and students. The quality of these clothing items is unknown, but in the later years of the system, survivors have spoken about feeling embarrassed due to the low quality of their clothing (Truth and Reconciliation Commission, 2015).

At various times Shingwauk was in desperate need of clothing, especially warm winter clothing like mits, caps, and coats, and many boys would have to continue on without these necessary items. Rev. Wilson commented in 1880 to a donor that they had 53 boys at the school but only 3 coats, and that the rest would have to be bought. However, the school was chronically underfunded and it’s hard to know if sufficient clothing was actually purchased. While there’s no evidence of students in the early years of Shingwauk dying of exposure, in the later years of the system students who ran away from other schools with clothing not suited to the winter climate sometimes did not make it home due to the poor clothing they received from the school. Lack of proper winter clothing also likely contributed to student illnesses such as tuberculosis, pneumonia, and fever.

In 1877, 4 years after the school first opened, Rev. Wilson decided to design a uniform for the students. The “uniform” part of the outfit consisted of a coat and cap, with the rest of the clothing still donated by patrons. Originally the winter coat and cap were black or grey tweed with scarlet piping and had brass buttons with the Shingwauk logo, and the summer outfit consisted of a dark blue overshirt with a band at the waist, a dark Garibaldi hat with a peacock feather, and grey trousers. For a while, the winter coats were made by the Hudson’s Bay Company, but later were made by local tailors and donors due to the expense. Girls uniforms were dresses in dark blue serge with red trim for winter, and were the same in summer but made out of cotton instead.

Rev. Wilson wanted the students to look very westernized, and often sent Shingwauk students home for the holidays in their uniforms because he felt they would be safer on the steamboats wearing that as opposed to any clothing which might come from their home. The uniforms were reserved for occasions like that when the boys would be out in public, such as trips to the church on Sundays, funding tours, or public events like the arrival of the Marquis of Lorne to Sault Ste Marie in 1881. The rest of the time the uniforms would be in storage.

Before the 1920s, attendance at Residential Schools was not compulsory, and principals had little power to retain students and stop them from running away, or stop parents from pulling them out of the school at any time. To combat this, many principals tried to fine parents for breaking attendance agreements, or in the case of Shingwauk, for taking school clothing. Rev. Wilson would fine parents anywhere from $5-$15 if their children failed to return when they had gone home with their uniforms. Being so far from his students’ home communities, Rev. Wilson often had a very difficult time trying to collect these fines, and tried to enlist the local Indian Agents to get the money. There are numerous letters to government officials such as the Superintendent General of Indian Affairs (at the time it was John A. Macdonald) asking for help and authority to collect the money. If the students did eventually return to the school, the charges would be dropped; most students did come back, and few clothing fines were actually collected.

In 1887, William Solomon actually travelled to Shingwauk after hearing a rumour that his son Wesley was going around without a shirt. Rev. Wilson looked into the situation and found that Wesley had ripped his shirt and thrown it away during free play time outside. He continued to play for a while before the teacher, Mr Mitchell, noticed this and brought him a new shirt. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission found multiple other examples of parents complaining about the quality of their children’s clothing, showing that they were not indifferent towards their children, and often took great pains to make sure that they were well cared for. This often included sending their children to school with beautiful handmade clothing, not knowing it would be discarded for clothing of poorer quality.

Today, many Indigenous people are using clothing as a way to retain their culture and proudly display their heritage. Riley Kucheran is a PhD student in the Fashion program at Ryerson University who is studying Indigenous fashion and received the 2019 Pierre Elliott Trudeau Foundation Scholarship for his work (Ryerson, 2019; CBC, 2019). Indigenous fashion designers are integrating traditional designs and techniques into their clothing, and supporting them is a great way to bring respect back to Indigenous style. Indigenous Fashion Week is an important event which highlights these designers; the event takes place in Toronto, Vancouver, and Ottawa (where it was held just this past week). More information about Toronto Indigenous Fashion Week can be found here, and a list of designers highlighted at Vancouver Indigenous Fashion Week can be found here.