2 Athletes First: The Promotion of Safe Sport in Canada

Erin Willson

Georgina Truman

Themes

Maltreatment in sport

Athlete-Centred approach

Change implementation

Learning Objectives

When you have completed this chapter, you will be able to:

L01 Identify four types of maltreatment;

L02 Draw connections between athlete advocacy and changes in sport;

L03 Identify 3 key changes;

L04 Explain how the athlete voice has led to key changes; and

L05 Identify key components of the athlete-centred approach. Provide suggestions to implement an athlete-centred sport system.

Overview

Maltreatment has become an increasingly documented concern in sport. For example, a 2019 study on Canadian National Team athletes revealed that 75% of athletes reported experiencing at least one harmful behaviour in their careers, with psychological harm and neglect being most common, followed by sexual and physical harm.[1] In Canada, the athlete’s voice has been an essential component of advancing the safe sport movement, which gained traction in 2018.

First, national team athletes completed a survey on their experiences of maltreatment,[2] which was closely followed by a gathering of athletes at the 2019 AthletesCAN Safe Sport Summit, in which reviewed the findings and established consensus statements on the prominent findings and next steps (e.g., a need for an independent body for disclosure/reporting).[3] These statements were presented at a National Safe Sport Summit, which included athletes, national sport organizations and multisport organizations, and led to the formation of a safe sport advisory board and action planning working group.

Since then, a Universal Code of Conduct to Prevent and Address Maltreatment in Sports (UCCMS) has been established and implemented, and a National Independent Mechanism (NIM) is being established by the Sport Dispute Resolution Centre of Canada (SDRCC). This chapter provides an overview of past actions athlete leaders have had in safe sport, including key learnings from this experience about why we believe the athlete’s voice is an essential component of driving change in sport.

This chapter includes multi-media content (videos/audio) of Canadian athletes sharing their experiences with maltreatment, disclosure/reporting concerns, and using their voices to create change. Additionally, it will provide an athlete’s perspective on what is essential to continue the movement toward a safer sport environment, and some practical examples of what safe sport looks like from the eyes of an athlete.

Key Dates

There has been mounting evidence of all forms of maltreatment occurring in sport around the world, including physical, sexual, and emotional abuse. Over the past decade, several high-profile cases have emerged, including the USA Gymnastics case in 2016, in which the team’s doctor Larry Nassar was sentenced to 175 years in prison after two hundred athletes came forward with experiences of sexual abuse.[4] The investigation also revealed a culture of emotional abuse and neglect that is rampant in the sport of artistic gymnastics. Athletes around the world have disclosed experiences of body shaming, forced extreme dieting and water restriction, training on injuries and concussions, and frequent public humiliation and beratement.[5] The USA Gymnastics case was not an isolated incident, with many sports facing similar cases and public allegations, including swimming, alpine skiing, rugby, and artistic swimming.[6] For instance, the British Athletes Commission called for a full investigation of British Gymnastics after several disturbing allegations of bullying and abuse arose in 2020.[7]

There have also been research studies conducted from several countries which assessed the prevalence of maltreatment occuring in Canada, Belgium, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom. These studies have indicated high rates of athlete maltreatment in areas including psychological abuse, neglect, physical abuse, and sexual maltreatment across sport.[8] For example, in a study of Canadian National Team athletes, seventy-six percent of athletes from sixty-four sports reported at least one experience of maltreatment in their athletic careers.[9]

In response to the growing awareness of maltreatment, several prevention and intervention initiatives have been instated. Some Canadian examples include the educational programs by Respect Group’s “Respect in Sport for Activity Leaders”, the Coaching Association of Canada’s Safe Sport Training, and mandatory requirements and standards for federally funded sport organizations, including third party reporting officers.

Most recently, a Universal Code of Conduct to Prevent and Address Maltreatment in Sport (UCCMS) has been implemented to outline all forms of harm in sport that are not acceptable. Furthermore, a National Independent Mechanism (NIM) has been developed to prevent and address maltreatment, and provide an independent body for athletes to report maltreatment. The latter initiatives were heavily influenced by athletes who had spoken out about personal experiences of maltreatment, highlighting the importance that the athletes’ voices carry in the movement towards a safer sport environment. In this chapter you will:

- Be able to explain the issue of maltreatment in sport within the Canadian context;

- Identify the ways in which athletes have influenced the Canadian sport system;

- Identify the steps required in adopting an athlete-centred approach; and

- Explain the importance of an athlete-centred approach in minimizing maltreatment within sport.

Overview of Maltreatment

Sport participation offers many benefits that lead to physical, social, and mental well-being (Hansen et al., 2003, Neely & Holt, 2014). However, it is important to acknowledge that there are athletes whose sport experiences have been harmful due to various forms of maltreatment.[10] Maltreatment refers to: “all types of physical and/or emotional ill-treatment, sexual abuse, neglect, negligence and commercial or other exploitation, which results in actual or potential harm to health, survival, development or dignity in the context of a relationship of responsibility, trust or power”.[11]

Table 2.1 Maltreatment Types and Examples[12]

| Type of Abuse | Example |

|---|---|

| Sexual Abuse | Touching or non-touching offenses (e.g., contact, exposure) |

| Physical Abuse | Punching, beating, kicking, biting |

| Psychological Abuse | Yelling, belittling, demeaning comments, humiliation |

| Neglect | Refusing recovery time of injury/illness, inadequate supervision, inadequate attention of basic needs |

| Bullying | Teammate exclusion, theft, teasing |

| Hazing | Initiation specific activities – drinking excessively, personal servant, performing criminal activities |

Use of Power

Power is a fundamental component of maltreatment because violence is often used to assert or maintain dominance over another person.[13] One example of a use of power to establish dominance is veteran athletes using their status as a means to force newcomers to partake in harmful hazing activities[14]

Hazing is frequently cited as a way for athletes to “know their place” on a team, which reinforces the player hierarchy with senior athletes holding their position of power over junior or new athletes.[15] As such, hazing is an example of maltreatment that can happen between peers. Although hazing can result between peers when a power differential occurs through age, rank, seniority, or skill level, it is important to note that athletes are typically prescribed equal amounts of power in the sport system making hazing between peers less likely to be addressed at an institutional level.[16]

There are several relationships in sport that have predisposed imbalances of power, which can often leave athletes vulnerable. Examples of these relationships include coach-athlete, team captain-athlete, trainer-athlete, and sport administrator-athlete (e.g., CEO of an NSO, high-performance director). Within each of these relationships, athletes are seen to be in a lower position of power since the other roles are positions of authority. Moreover, there is increased vulnerability because of the culture of control and obedience that is instilled throughout sport.

Athletes are taught to respect these positions of authority, which can lead to an unquestioned compliance to the demands from someone in a higher position (e.g., coach).[17] Moreover, this compliance is often expected from those people who are in positions of power. This power imbalance and unquestioned compliance can significantly reduce an athlete’s power since they are conditioned not to deviate from what is expected of them.

Therefore, our stance at AthletesCAN is to empower athletes by including them in important conversations about their training in order to lessen the power imbalances inherent in sport. It is our hope that steps taken to nurture athlete empowerment will contest traditional methods of coaching and reduce athlete vulnerability .

For more insight about the history of athletes’ involvement in the high-performance sport system, review these resources. In his 2006 thesis and co-authored research article with Dr. Ian Ritchie, Greg Jackson examined the involvement of athletes in Canada’s anti-doping policy process.

Differentiation between Relationships and Forms of Maltreatment

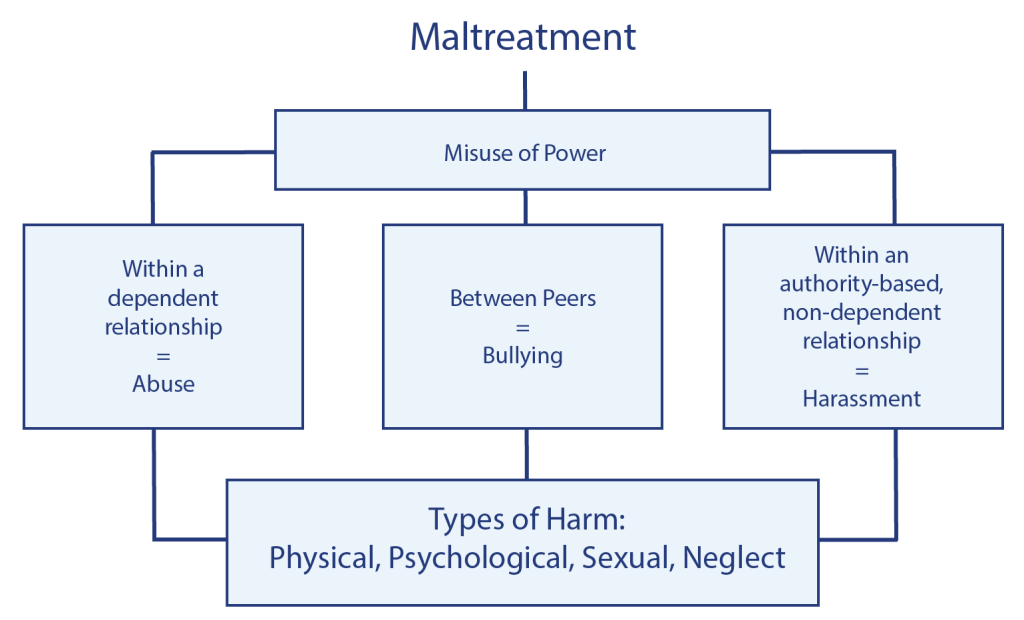

Several terms are frequently interchanged when discussing maltreatment in sport. Therefore, this section provides an overview of the different terminologies that are used. Figure 3.1 outlines these terms in a more concise way and is broken down based on the positions of power. The figure indicates that a misuse of power is the underlying mechanism of harm. Abuse is harm that occurs between two actors, with one person having significant influence over another’s sense of security, trust, and/or fulfillment of needs.[18] This is often known as a “critical relationship,” and in sport this can be relationships between athletes and authority figures that commonly interact (e.g., coaches, parents, etc.). Maltreatment between peers is referred to as bullying since athletes are typically within the same prescribed social rank, and in most instances do not have the power differential of a critical relationship. Harassment is maltreatment that occurs outside of a critical relationship. There is typically a power imbalance that occurs between the two actors; however, the perpetrator does not have a direct influence on the others sense of safety or trust. Examples of this could be a sport administrator that only interacts with the athletes occasionally. At the bottom of the diagram are the types of harm that can occur, which will be discussed in the following section.

Figure 2.1 Differentiation Between Relationships and Terms Including Bullying, Abuse, and Harassment

Four Types of Maltreatment

1. Psychological Harm

Psychological harm in sport is defined as “a pattern of deliberate non-contact behaviours that have the potential to be harmful” (Stirling & Kerr, 2008, p. 178). Psychological abuse has been found to be the most frequently experienced type of harm by athletes.[19] Psychological abuse accounts for many harmful behaviours including being yelled at and publicly humiliated. Given the nature of sport, these types of harmful behaviour occur routinely, resulting in the normalization of abusive behaviour and higher rates of psychological harm. Simply put, these behaviours occur so frequently in public training environments that they have become accepted as “part of the game”.[20]

Stirling and Kerr (2008) have proposed examples of psychological harm, which include:

- Physical behaviours:

- Throwing objects at or around athletes (e.g., flutter boards);

- Physical demonstrations of anger; and

- Physical intimidation.

- Verbal behaviours:

- Demeaning, humiliating, belittling comments;

- Insults;

- Swearing at an athlete;

- Name-calling, criticism of a person;

- Threats; and

- Body shaming and negative comments about the body.

- Denial of attention:

- Ignoring athletes due to poor performance; and

- Expelling athletes from practice.

The most common behaviours reported by Canadian athletes in 2019 were being shouted at, being gossiped about or having lies told about them, and being put down, embarrassed or humiliated.[21]

Video 2.1 Erin Willson: Body Image and Belittling Athletes

2. Physical Harm

Physical harm is understood to be an infliction of physical pain or injury, which can include contact or non-contact behaviors.[22] Contact behaviours include hitting, slapping, and punching, whereas non-contact behaviours can include being forced to hold an uncomfortable position for a prolonged period of time.

Physical harm in sport can be:[23]

- Exercise as punishment;

- Stretching to the point of injury;

- Hitting an athlete with sports equipment;

- Returning to play prematurely after injury; and

- Excessive repetition of skill to the point of injury.

Exercise as punishment (e.g., running laps when late, doing sprints because of poor performance) was the most frequently reported form of physical harm by Canadian athletes in 2019.[24]

3. Sexual Harm

Sexual harm is understood as “Any sexual interaction with person(s) of any age that is perpetrated against the victim’s will, without consent, or in an aggressive, exploitative, coercive, manipulative, or threatening manner”.[25]

Sexual harm in sport can be contact or non-contact including, but not limited to:

- Touching;

- Intercourse;

- Reward for sexual favour;

- Indecent exposure;

- Sexually oriented comments or jokes;

- Intimidating sexual remarks;

- Sexting; and

- Intrusive sexual glances.

The most frequent forms of sexual harm reported amongst Canadian athletes were sexist jokes and remarks and intrusive sexual glances, sexually explicit communication, and sexually inappropriate touching.[26]

4. Neglect

Neglect is characterized by acts of omission or inaction.[27] Examples of this are intentionally ignoring someone or their needs, purposeful exclusion, or purposeful inaction.

- Some of the ways this can be seen in sport include, but are not limited to:[28]

- Failing to provide adequate hydration, nutrition, medical attention, or sleep;

- Ignoring an injury or athlete’s report of pain;

- Knowing about abuse but failing to report; and

- Denial of non-sport, developmentally valuable experiences (e.g., education, job opportunities).

Training when injured or exhausted, sacrificing education and/or career, training in unsafe conditions, and inadequate support of basic needs were the most frequently identified behaviours by Canadian athletes.[29]

Video 2.2 Allison Forsyth: What is Complicity?

Video provided by Dr. Michele Donnelly, Panel Moderator and Dr. Michael Van Bussel, Conference Chair, 2021 Safe Sport Forum; and Dr. Julie Stevens, Director, Centre for Sport Capacity, Brock University, Brock University. Used with permission. [Transcript]

Case Study:

Identifying Types of Harm

In the middle of the season, a high-performance gymnast was complaining of pain in her heel. Their doctor advised her to take it easy at practice for a month since it could lead to a tear in her Achilles’ heel. Her coach put her on a modified training program, so she would do primary upper body, core, and flexibility training on her own.

The athlete was mostly ignored by the coach because the coach would focus on the other athletes who were “there to train”. One example of the modified training was being told to hold a split position for five minutes on each leg and if her coach felt she was not as flat in her splits as she could be, then the coach would come by and press down on her shoulders to make her legs touch the ground.

Often, tears were formed in the athlete’s eyes because of the sharp pain this extra pressure would cause. She was diligent about training plan but if her coach ever saw her “taking it easy” even if it was for a water or bathroom break, the athlete would be yelled at from across the gym and humiliated in front of all the other gymnasts. As a consequence, she would be forced to complete one hundred push ups and one hundred sit ups to make up for the perceived lack of effort.

Two weeks before the upcoming qualification, the coach told her that if she did not start participating in full practices, she would not be allowed to compete in the qualification which meant she would not be eligible for the larger competitions that season. Knowing this, the athlete decided that she would train full-time against their doctor’s orders.

Which of the four types of harm are being seen here?

AthletesCAN, the association of Canada’s national team athletes, is the only fully independent and most inclusive athlete organization in the country and the first organization of its kind in the world. As the collective voice of Canadian national team athletes, AthletesCAN ensures an athlete-centred sport system by developing athlete leaders who influence sport policy and, as role models, inspire a strong sport culture.

AthletesCAN, the association of Canada’s national team athletes, is the only fully independent and most inclusive athlete organization in the country and the first organization of its kind in the world. As the collective voice of Canadian national team athletes, AthletesCAN ensures an athlete-centred sport system by developing athlete leaders who influence sport policy and, as role models, inspire a strong sport culture.AthletesCAN: First in Canada to Hear the Athletes’ Voices

In 2019, AthletesCAN, in partnership with the University of Toronto, and with the support of the Government of Canada, announced that a baseline prevalence study would be carried out to provide a snapshot of Canada’s national team athletes’ experiences with abuse, harassment and discrimination in sport.

About AthletesCAN

AthletesCAN, the association of Canada’s national team athletes, is the only fully independent and most inclusive athlete organization in the country. It is also the first organization of its kind in the world. As the collective voice of Canadian national team athletes, AthletesCAN ensures an athlete-centred sport system by developing athlete leaders who influence sport policy and, as role models, inspire a strong sport culture.

Mission: To unite and amplify the voices of all Canadian National Team athletes.

Vision: We are the collective athlete voice in the unwavering pursuit of an athlete-centred sport system.

Values: AthletesCAN promotes and lives the following athlete focused values in our work and through our actions

- Integrity: We lead with an honest and moral approach to everything we do;

- Courage: We find the strength to stand up for what is right;

- Inclusivity: We represent a diverse membership and support the voices of all athletes; and

- Transparency: We are open and vulnerable in our effort to create a better sport system.

AthletesCAN History

AthletesCAN serves an important and unique purpose in sport. Led by a committed group of current and retired national team athletes – AthletesCAN benefits from a rich history.

Over two decades ago, passionate trailblazers including three-time World Indoor Championship bronze medalist and Pan-Am Champion Ann Peel (Race Walking); two-time Commonwealth Games Champion and two-time Pan-Am Games silver medalist Dan Thompson (Swimming); ‘Crazy Canuck’ and Olympic bronze medalist Steve Podborski (Alpine Skiing); 1988 Olympian, Heather Clarke (Rowing); 2-time Olympic Champion Kay Worthington (Rowing); 1984 Olympian, Sandra Levy (Field Hockey); 1984 and 1988 Olympian, Shelley Steiner (Fencing), Tour de France Women’s Champion, Pan-Am Games bronze medallist and 2012 and 2016 Olympic coach, Denise Kelly (Cycling); and former CEO of Freestyle Canada Bruce Robinson, came together to challenge the Canadian sport system.

They identified the need for and founded an independent body, then known as the Canadian Athletes Association, that would represent all national team athletes as a stronger collective voice on key issues and initiatives in sport. These early days helped to build an increasingly athlete-centred sport system and provided hundreds of athletes with the opportunity to contribute in a number of important ways.

Since then, AthletesCAN has invested in athlete leadership development through effective representation and education. The organization has created resources to build and formalize athlete feedback mechanisms across the sport system. As a result of strengthening strategic partnerships both within and outside of the system, AthletesCAN has continued to pioneer innovative ways to ensure inclusive decision-making by informing, educating, and advocating for an athlete-centred sport system. One of the major contributions in the past few years to the Canadian sport system was ensuring athletes’ voices were heard in the safe sport discussions and policy formations. One of the ways this was done was through a formalized research study in partnership with the University of Toronto, in which athletes were asked about their experiences of maltreatment in sport.

AthletesCAN & Prevalence

The last prevalence study of Canadian athletes’ experiences was conducted over twenty years ago.[30] Since that time, the culture with respect to reporting sexual violence as well as child and youth protection has changed dramatically. Not only does this current prevalence study provide a snapshot of athletes’ experiences but it serves as baseline data against which to assess the impact of future preventive and intervention initiatives. It also signals the importance of addressing the human rights and welfare of athletes in Canada.

The online, anonymous survey was developed by Dr. Gretchen Kerr, Ph.D., Erin Willson, Ph.D. Candidate, and Ashley Stirling, Ph.D., in collaboration with AthletesCAN and the AthletesCAN safe sport working group. The survey was distributed to current national team members as well as retired national team members who had left the sport within the past ten years.

In total, 1,001 athletes participated in the study by completing an online survey. Of this total, seven-hundred-sixty-four were current athletes and two-hundred-thirty-seven were retired athletes who had left their sport within the past ten years.

A discussion of the study’s results is provided in Chapter 17.

Athlete Consensus Statements

In 2019, AthletesCAN, together with their partners, hosted the AthletesCAN Safe Sport Summit in Toronto, Ontario. The event brought together fifty athletes, sport partners, subject matter experts, survivors, and advocates to courageously share their experiences, knowledge, and vision for a safer sport environment from grassroots to high-performance. The results from the prevalence study conducted by Kerr et al., (2019) were shared with the athletes (see Chapter 21 for more information).

After meaningful discussions, the athletes agreed to a number of consensus statements, including, but not limited to the following:

- That all forms of maltreatment be prohibited.

- For athletes above the age of 18 years:

- Any sexual relations between a person in a position of authority and an athlete is prohibited as it creates a perceived bias, perceived conflict of interest, negative implications for other teammates, and an imbalance of power that puts an athlete’s ability to consent in question.

- Upon implementation of this code, any sexual relationship that has been initiated between a person in a position of authority and an athlete must be disclosed and the person in the position of authority must leave the organization. Failure to disclose should result in sanctions.

- Retaliation against an athlete who has not consented to sexual advances or solicitation of sexual conduct or relationships is strictly prohibited and should be sanctioned accordingly.

- That a Safe Sport Canada body be established and responsible for all aspects of Safe Sport including but not limited to policy, education and training, investigation and adjudication, support and compensation.

- That Safe Sport Canada be independent of all other sport governing bodies.

- That there be a universal code of conduct that applies to all stakeholders and addresses all forms of maltreatment and applicable sanctions.

- That there be mandatory education on Safe Sport for all stakeholders driven by minimum and harmonized standards to ensure good standing.

Read the following section to better understand the extent to which each of these six consensus statements has been fulfilled.

Key Learnings

Over the past few years there have been significant shifts towards a safe sport environment in Canada. AthletesCAN believes the driving forces of this shift have risen because of the strength in the athletes’ voices. Athletes came together to ensure that safety in sport was a main priority for sport administrators. They did this through formalized surveys and unified consensus statements to ensure their requests and proposed actions for meaningful change were heard. In addition, the Safe Sport Working Group was formed through AthletesCAN as a group of current and retired athletes to represent the collective athlete voice at national practitioner conferences, and in the committees responsible for creating the UCCMS and NIM. As demonstrated by the timeline presented at the beginning of this chapter, many of the critical steps occurred based on the consensus statements from the athletes in 2019.

Explanations of the Consensus Statements from the 2019 AthletesCAN Safe Sport Summit

Statement #1 reads that all forms of maltreatment should be taken into consideration. Previously, the prevention and intervention initiatives in sport had been primarily focused on sexual harm, with policies such as the “Rule of 2” implemented to protect young athletes from being alone with potential sexual perpetrators[31] (see Chapter 17 for more information on coaching and the “Rule of Two”). The implementation of the UCCMS outlines all forms of unacceptable harm , which includes sexual, physical, physiological and neglectful behaviors.[32]

Statement #2 which pertains to all athletes regardless of age, is also incorporated within the UCCMS. The UCCMS does not specify age because there is the understanding that the behaviors outlined can be harmful at any age.[33]

Statements #3 and #4 were addressed in 2021 when the National Independent Mechanism (NIM) was established. While the body is not completely independent since it is run through an existing organization, it is a 3rd party resource that equally advocates for all parties (athletes, coaches, sport administrators). In addition, the NIM is also responsible for research, education, and training (statement #3).

Statement #5 has been addressed with the creation and implementation of the Universal Code of Conduct to Prevent and Address Maltreatment in Sport.

Statement #6 has also been addressed through mandatory education that is being provided through the Coaching Association of Canada that was created in 2020. At this time, safe sport training is mandatory for all stakeholders, but there is a lack of data to assess whether this is being upheld.

Given these changes aligned with athletes’ requests, AthletesCAN believes that athletes were an essential part of this movement. However, it is also interesting to note that many decisions made about athletes do not incorporate athletes themselves. For example, many athletes do not have representation or voting rights on their sport organizations’ Board of Directors where many decisions are made. We implore sport organizations to continue collecting feedback from their athletes and incorporating athletes in their decision-making processes. This can be done through formalizing athlete representation into government structures and practices.

Video 2.3 Danielle Lappage: Attending the AthletesCAN Safe Sport Summit

Video provided by AthletesCAN. Used with permission. [Transcript]

“Canadian athletes have a proud history of representing this country with honour, class, and overall success. NSOs in Canada work hard to provide the structures which contribute to our athletes’ achievements. In order to best utilize these structures, it is paramount for athletes to both literally and figuratively have a seat at the table. In addition, by including the athlete voice in NSO decision making and governance, Canadian sport institutions will increase their level of effectiveness and transparency, while promoting democratic ideals. Acts of good faith, inclusivity, and a will for success are all virtues needed for promoting the voice of athletes within Canadian sport governance.” – AthletesCAN, 2020

Read the full report “The Future of Athlete Representation within Governance Structures of National Sport Organizations” online.[34]

Athlete-Centred Approach

An athlete-centred approach allows athletes to take a more active role in their sporting career, particularly around the decision-making process. Jowett and Cockerill (2003) propose that this approach minimizes the dependency of an athlete on the coach, by becoming an equal contributor in the process. In the 1994 discussion paper “Athlete-Centred Sport” Clarke, Smith and Thibault discuss properties of an athlete-centred sport system:

- In an athlete-centred sport system, the values, programs, policies, resource allocation and priorities should be based on athletes’ needs and goals;

- “The primary focus of sport should be to contribute to the all-round development of athletes as whole, healthy people through sport;”

- “Athletes are the ‘raison d’etre’ of the sport system. Therefore, in order to maintain the integrity and value of sport, it is critical that the sport experience be positive for athletes;”

- Athletes are the ACTIVE SUBJECTS, not the objects of sport.

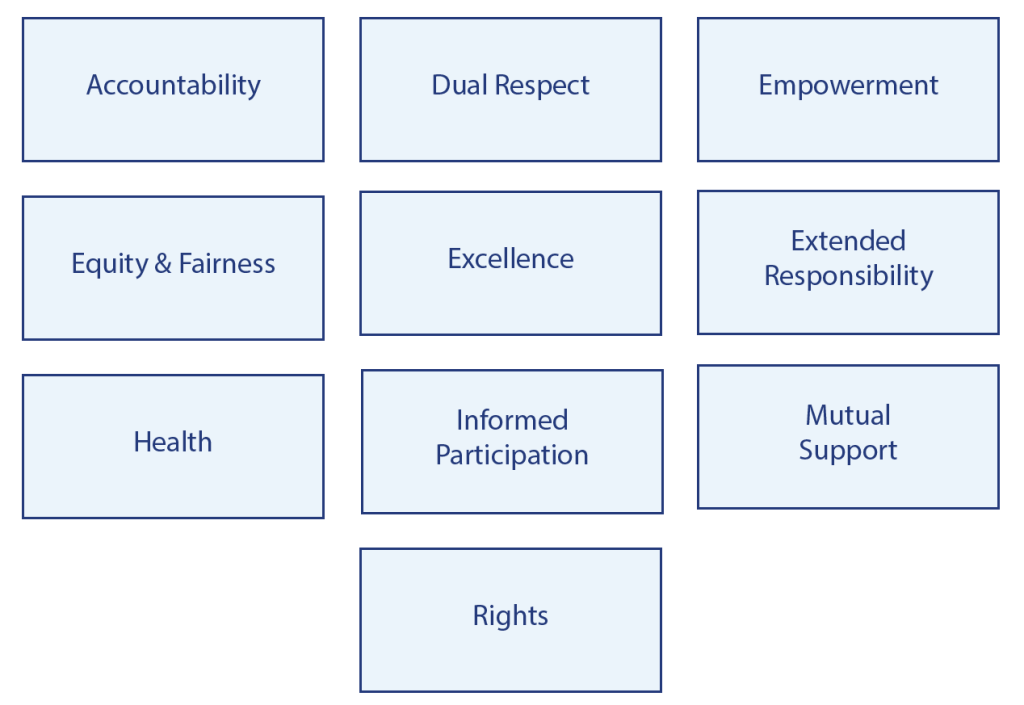

Figure 2.2 Characteristics of an Athlete-Centred System

Canada’s Formal Commitment to an “Athlete-Centred Approach”

Background

After the 1988 Ben Johnson doping incident, a formal inquiry was conducted to assess the sport environment.[35] This investigation was conducted by Ontario Appeal Court Chief Justice Charles Dubin and was known as the “Dubin Inquiry”. Results from this investigation posited that the win-at-all costs approach that was rampant throughout the Canadian sport culture was detrimental to the health and well-being of athletes.[36] Following this commission, Canada began to make changes towards a more athlete-centred approach, which included the creation of AthletesCAN in 1992 and the Canadian Centre for Ethics in Sport (CCES), then known as the Canadian Anti-Doping Organization (CADO).

Canada has made formal commitments to an athlete-centred approach through policy documents including:

- 2003 Canadian Sport Policy

- This policy outlined 4 major goals of Canadian Sport: Enhanced Participation, Enhanced Excellence, Enhanced Capacity, and Enhanced Interaction. The widening of these goals indicated that participation in sport is not only about high-performance but recognizes that participation of all people would be beneficial to the well-being of the Canadian population.[37]

- 2019 High-Performance Sport Strategy “Good Governance”

- Mandates “Canadians are systematically achieving world-class results at the highest levels of international competition through fair and ethical means”.[38]

Case Study:

Ben Johnson’s Doping Scandal

“Dealing with doping: Sports world can learn from Canada and Ben Johnson legacy” by Sarah Bridge, CBC, Feb. 12, 2018.

At the 1988 Summer Olympics in Seoul, South Korea, Canadian Olympic sprinter Ben Johnson won the gold medal in the 100 meter sprint in 9.79 seconds. It was later discovered that he and five other finalists had taken performance-enhancing drugs. What followed was the Dubin inquiry, a historic commission that revealed the ineffective testing policies and procedures of the Canadian government. This inquiry spurred by Johnson’s doping revelations resulted in the establishment of the Canadian Anti-Doping Organization (CADO), an independent body that oversees nationwide drug testing. The CADO is known today as the Canadian Centre for Ethics in Sport (CCES). The Dubin Inquiry focused upon high-performance athletes rather than the sport system as a whole when identifying reasons why performance enhancing drugs were prevalent in Canadian high-performance sport.

What do you think sport leaders have learned from this scandal about implementing an athlete-centred approach? What lessons still need to be implemented?

Video 2.4 Camille Bérubé: An Athlete’s Perspective on Safe Sport

Video provided by AthletesCAN. Used with permission. [Transcript].

Perceived Barriers for Athletes

One of the main challenges identified by athletes is that they do not feel they have a safe place to report maltreatment. Most complaints must be brought to the athletes’ superiors, who have power over the decisions that are made against the athlete. For example, a national team athlete who had an issue with a coach would need to go to the national sport organization to submit a complaint, but this could also have implications for their own careers since the sport organizations makes decisions on team selection. Many athletes feel as though they do not have a safe place to report their experiences.

Video 2.5 Neville Wright: An Athlete’s Perspective on Racial Discrimination in Sport

Video provided by AthletesCAN. Used with permission. [Transcript]

During her presentation at the 2021 Safe Sport Forum hosted by the Centre for Sport Capacity at Brock University, Allison Forsyth, Olympian and AthletesCAN board member, addressed the difficulty an athlete faces when reporting maltreatment. The following six themes related to perceived barriers are highlighted by these direct quotes provided by athlete participants in the maltreatment study.[39]

Theme 1: Lack of safe reporting

“While some could view the outcomes of this study as negative, highlighting the extreme nature of the issues and having a baseline to then work from to effect change is actually positive.”

“Athletes rarely report. Plain and simple. They are not comfortable or feel safe doing so with anyone who has a vested interest in the outcome. I reported and did not experience a positive outcome. It is not easy being the whistle blower. We need to support athletes through this – they need a safe place to report free from conflict of interest.”

“The reporting system is broken or useless as it stands right now. Other coaches knew about abuse and did nothing. Turning a blind eye was the norm. Everyone feared consequences of confronting the issues.”

“When an athlete or team says that the coach is unfit and that her behaviour is considered harassment, listen! It is not ok to “wait and see” what will happen and expect that all problems will resolve themselves. When twelve people give you different instances of unacceptable behaviours, that means there is a problem, don’t tell your athletes that they are “just being dramatic and will have to deal with it.”

“I did not make a formal complaint because the process was lengthy and I was afraid of repercussions and mentally it would be difficult to deal with and continue training.”

“If athletes speak out or questions decisions, they are told to be quiet.”

Theme 2: No whistleblower protection

“My NSO did support me very well during a harassment investigation. The parties accused were found guilty but very minor consequences were given. The harassment put a cloud over my entire career.”

Theme 3: Lack of meaningful consequences

“Over 5 players have left our program due to mental health issues in direct correlation with the head coach. Our team finished 3rd so they kept him on board despite the abuse.”

Theme 4: Not being included in conversations and lack of formal representation

Athletes’ voices are often ignored in the conversation of maltreatment. Reasons athletes have received for not being included are:

- Current athletes have a conflict of interest;

- Current athletes do not have the expertise in this area;

- Athletes do not have a formalized role to provide feedback.

“This included the use of conflict of interest to exclude athlete representative positions from NSO boards, issues with recruiting athlete representatives who lack the preferred board member skills and qualifications, as well as geographical barriers which may prevent athletes from attending board meetings and performing their athlete representative role.”[40]

Theme 5: Lack of education on right vs. wrong

Normalization of behaviours, grooming contributes to a lack of education.

“All athletes, coaches and sports officials should take a mandatory Safe Sport course.”

“Coaches should be required to go through training to help them navigate harassment and abuse issues between team members. My coach always put his head in the sand and used the ‘that’s not my job’ excuse. I know there is a focus on dealing with harassment and abuse perpetrated by coaches, but I think that issues between peers also must be seriously addressed.”

Theme 6: Call for More Education

“More education is needed on ‘It’s not okay to do X’ anymore.”

“Teach male coaches that it isn’t appropriate to talk about sexual things, whether or not they relate to the athlete, ever. Teach coaches to not discuss the negatives of their personal/home life with the athlete, ever.” As one athlete wrote, “Coaches are educators. Most math teachers would be fired for negatively screaming at a person for a wrong answer. Out with the old in with the new.”

Conclusions and A Way Forward

Video 2.6 Erin Willson: The Definition of Safe Sport

Video provided by Dr. Michele Donnelly, Panel Moderator and Dr. Michael Van Bussel, Conference Chair, 2021 Safe Sport Forum; and Dr. Julie Stevens, Director, Centre for Sport Capacity, Brock University. Used with permission. [Transcript]

There continues to be improvements and action toward a safer sport environment for all, however, there is still great deal that must be done. We believe one of the most essential parts of this movement are the athletes, which includes their protection and their voice within this movement. We believe the best way forward is through a collaborative approach with all stakeholders, including sport administrators, sport organizations, coaches, and athletes. This does not necessarily mean that athletes get “all the power” but we do propose that athletes are involved in a meaningful way.

Moreover, this means removing the “us vs. them” mentality that continues to persist between sport stakeholders, specifically between athletes and other stakeholders. There are concerns that if athletes have more power then there will be chaos in sport, and it will no longer be manageable. We are at a moment in time where athletes are demanding protection, and we believe that a system that includes all stakeholders’ voices and puts athletes at the centre of all decisions will lead to a safe, welcoming, and inclusive sport environment.

Key Terms

Suggested Assignments

- The 1990 Dubin Inquiry, titled the “Commission of Inquiry into the Use of Drugs and Banned Practices Intended to Increase Athletic Performance” summarizes the facts and circumstances surrounding the use of drugs and banned substances intended to increase athletic performance. Review the recommendations noted in Chapter 26 of the report. Has the Canadian sport system met the recommendations Dubin proposed? Why or why not?

- A 2017 study by Laurie de Grace at the University of Alberta found that sport culture can push athletes towards drug and alcohol addiction to cope with pressure. Review the CBC’s report “Part of the Culture: Study suggests links between sports and addiction.” How might an athlete-centred approach reduce the risk of alcohol and drug dependency for athletes?

- Read “Next Steps in the Safe Sport Journey: From Prevention of Harm to Optimizing Experiences” by Gretchen Kerr and consider the following questions:

- In your perspective, what elements would create a safe, welcoming, and inclusive sport environment?

- What social influences on sport increased the focus on human rights?

- Why might a coach, or sport administrator resist change with respect to safe sport? List one example for each of the stages of change.

- Review “The Future of Athlete Representation within Governance Structures of National Sport Organizations” from AthletesCAN and consider the following questions:

- How did the 2011 Canada non-for-profit act impact athlete representation on NSO Boards?

- What are prominent concerns and areas of concensus in the sport system around athlete-centred approach to governance?

- In your opinion, where would you place Canadian NSOs on the athlete representation continuum and how does this impact Canada’s athlete-centred approach? How does this impact the athlete-centred approach regarding safe sport? How would a shift to the democratic end of the continuum?

Figure Descriptions

Figure 2.1 This figure demonstrates the differentiation between relationships and terms including bullying, abuse, and harassment. Maltreatment is committed through the misuse of power. Within a dependent relationship this is called abuse. Between peers this is called bullying. Within an authority-based, non-dependent relationship this is called harassment. These three types of harm are manifested in physical, psychological and sexual harm, as well as neglect. [return to text]

Figure 2.2 This figure demonstrates the nine characteristics of an athlete-centred system which include accountability, dual respect, empowerment, equity & fairness, excellence, extended responsibility, health, informed participation, mutual support, and rights. [return to text]

Sources

Alexander, K., Stafford, A., & Lewis, R. (2011). The experiences of children participating in organized sport in the UK. The University of Edinburgh: Child Protection Research Centre.

Allan, E. J., Kerschner, D., & Payne, J. M. (2019). College student hazing experiences, attitudes, and perceptions: Implications for prevention. Journal of Student Affairs Research and Practice, 56 (1), 32-48. https://doi.org/10.1080/19496591.2018.1490303

AthletesCAN. (2019, May 2). Athlete leaders unite to influence safe sport policy in Canada. Retrieved December 30, 2021, from https://athletescan.com/en/athlete-leaders-unite-influence-safe-sport-policy-canada

AthletesCAN. (2020). The future of athlete representation within governance structures of national sport organizations. https://athletescan.com/sites/default/files/images/the_future_of_athlete_representation_in_canadavf-en3.pdf

AthletesCAN. (n.d.a). Retrieved December 30, 2021, from https://athletescan.com/en

AthletesCAN. (n.d.b). Our story. Retrieved December 30, 2021, from https://athletescan.com/en/about/our-story

BBC News. (2018, January 25). Larry Nassar case: The 156 women who confronted a predator. Retrieved December 30, 2021, from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-42725339

Brackenridge, C. H. (1994). Fair play or fair game? Child sexual abuse in sport organisations. International review for the Sociology of Sport, 29(3), 287-298.

Brittain, C. R. (2006). Defining child abuse and neglect. Understanding the medical diagnosis of child maltreatment: A guide for nonmedical professionals, 149-189.

Burke, M. (2001). Obeying until it hurts: Coach-athlete relationships. Journal of the Philosophy of Sport, 28(2), 227-240.

Canadian Centre for Ethics in Sport. (n.d.). History of anti-doping in Canada. Retrieved December 28, 2021, from https://cces.ca/history-anti-doping-canada

Canadian Heritage. (2021, July 6). Minister Guilbeault announces new independent safe sport mechanism. Government of Canada. Retrieved October 27, 2021, from https://www.canada.ca/en/canadian-heritage/news/2021/07/minister-guilbeault-announces-new-independent-safe-sport-mechanism.html

Canadian Safe Sport Program. (n.d.). Sport Information Resource Centre: Universal Code of Conduct to Prevent and Address Maltreatment in Sport (UCCMS), 5(1), 1-16. https://sirc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/UCCMS-v5.1-FINAL-Eng.pdf

Clarke, H., Smith, D., & Thibault, G. (1994). Athlete-centred sport: A discussion paper. https://athletescan.com/sites/default/files/images/athlete-centred-sport-discussion-paper.pdf

Coaching Association of Canada. (n.d.). Three steps to responsible coaching. Retrieved December 28, 2021, from https://coach.ca/three-steps-responsible-coaching

Comeau, G. S. (2013). The evolution of Canadian sport policy. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 5(1), 73–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/19406940.2012.694368

Crooks, C. V., & Wolfe, D. A. (2007). Child abuse and neglect. In E. J. Mash & R.A. Barkley, (Eds). Assessment of Childhood Disorders (4th ed.). New York: Guilford Press, 1–17.

Davidson, N. (2021, April 28). Ruby 7s women say they were let down by Rugby Canada’s bullying/harassment policy. The Canadian Press. Retrieved December 28, 2021, from https://www.cbc.ca/sports/rugby/rugby-sevens-women-let-down-rugby-canada-bullying-harrassment-policy-1.6005901

Dichter, M. (2021, October 8). NWSL’s abuse scandal reveals normalization of toxic culture in sports. CBC Sports. Retrieved December 30, 2021, from https://www.cbc.ca/sports/soccer/nwsl-soccer-abuse-symptom-culture-1.6204197

Dubin, C. L. (1990). Commission of inquiry into the use of drugs and banned practices intended to increased athletic performance. The Honourable Charles L. Dubin Commissioner.

Durrant, J. (2006) Distinguishing physical punishment from physical abuse: Implications for professionals. Canada’s Children, 9, 17–2.

Ehekircher, S. (2020, April 25). My swim coach raped me when I was 17. USA swimming made it disappear. The Guardian. Retrieved December 28, 2021, from https://www.theguardian.com/sport/2020/aug/25/my-swim-coach-raped-me-when-i-was-17-usa-swimming-made-it-disappear

Government of Canada. (2017). Sport in Canada. Retrieved December 30, 2021, from https://www.canada.ca/en/canadian-heritage/services/sport-canada.html

Gymnast Alliance. (n.d.). #GymnastAlliance – Changing the gymnastics worlds. https://www.google.com/search?q=gymnast+alliance&oq=gymnast+alliance&aqs=chrome.0.69i59j0i512l2j0i22i30l2j69i60l2j69i61.3492j0j4&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8

Hansen, D. M., Larson, R. W., & Dworkin, J. B. (2003). What adolescents learn in organized youth activities: A survey of self-reported developmental experiences. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 13(1), 25–55. https://doi.org/10.1111/1532-7795.1301006

Hu, L., & Liu, Y. (2017). Abuse for status: A social dominance perspective of abusive supervision. Human Resource Management Review, 27(2), 328-337.

Ingle, S. (2021, March 9). Interim report reveals 400 submissions over UK gymnastics abuse. The Guardian. Retrieved December 30, 2021, from https://www.theguardian.com/sport/2021/mar/09/british-gymnastics-abuse-review-interim-report-400-submissions-uk

Jackson, G. (2006). A critical examination of the involvement of Canadian high-performance athletes in the development of anti-doping policy. Brock University. https://dr.library.brocku.ca/bitstream/handle/10464/1215/Brock_Jackson_Gregory_2006.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Jenkins, S. (2018, March 14). Aly Raisman: Conditions at Karolyi Ranch made athletes vulnerable to Nassar. The Washington Post. Retrieved December 30, 2021, from https://www.washingtonpost.com/sports/olympics/aly-raisman-conditions-at-karolyi-ranch-made-athletes-vulnerable-to-nassar/2018/03/14/6d2dae56-26eb-11e8-874b-d517e912f125_story.html

Jowett, S., & Cockerill, I. M. (2003). Olympic medallists’ perspectives of the athlete-coach relationship. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 4(4), 313–331. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1469-0292(02)00011-0

Kerr, G., Jewett, R., Macpherson, E., & Stirling, A. (2016). Student-athletes’ experiences of bullying on intercollegiate teams. Journal for the Study of Sports and Athletes in Education, 10(2), 132-149. DOI: 10.1080/19357397.2016.1218648

Kerr, G., Willson, E., & Stirling, A. (2019). Prevalence of maltreatment among current and former national team athletes. University of Toronto. 1–51. https://athletescan.com/sites/default/files/images/prevalence_of_maltreatment_reporteng.pdf

Kirby, S., & Greaves, L. (1996, July). Foul play: Sexual harassment and abuse in sport. Paper presented at the Pre-Olympic Scientific Congress, Dallas, TX.

Levenson, E. (2018, January 24). Larry Nassar sentenced to up to 175 years in prison for decades of sexual abuse. CNN. Retrieved December 28, 2021, from https://www.cnn.com/2018/01/24/us/larry-nassar-sentencing/index.html

Longman, J., & Brassil, G. R. (2021, March 9). Complaints of emotional abuse roil synchronized swimming. The New York Times. Retrieved December 28, 2021, from https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/09/sports/olympics/synchronized-swimmers-abuse.html

Madger, J. (2017, March 14). McGill basketball teams in spotlight for brutal hazing allegation. Montreal Gazette. Retrieved December 30, 2021, from https://montrealgazette.com/news/local-news/mcgill-basketball-teams-in-spotlight-for-brutal-hazing-allegation

Muchnick, I. (2021, April 25). Dead in the water: The tragic human cost of swimming’s abuse scandals. Salon. Retrieved December 28, 2021, from https://www.salon.com/2021/04/25/dead-in-the-water-the-tragic-human-cost-of-swimmings-abuse-scandals/

Neely, K. C., & Holt, N. L. (2014). Parents’ perspectives on the benefits of sport participation for young children. The Sport Psychologist, 28(3), 255-268.

Parent, S., & Vaillancourt-Morel, M. P. (2020). Magnitude and risk factors for interpersonal violence experienced by Canadian teenagers in the sport context. Journal of Sport and Social Issues. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193723520973571

Pence, E., & Paymar, M. (1986). Power and control: Tactics of men who batter. Duluth, MN: Minnesota Program Development.

Perry, B., Mann, D., Corel, A., & Ludy-Dobson, C. (2002). Child physical abuse. In D. Levinson (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Crime and Punishment (pp. 197–202). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Respect in Sport. (n.d.). Retrieved December 30, 2021, from https://www.respectgroupinc.com/respect-in-sport/

(2014). Politics and ‘shock’: reactionary anti-doping policy objectives in Canadian and international sport. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 6(2), 195-212. DOI: 10.1080/19406940.2013.773358

Russo, N. F., & Pirlott, A. (2006). Gender-based violence: concepts, methods, and findings. In F. L. Denmark, H. H. Krauss, E. Halpern, & J. A. Sechzer (Eds.), Annals of the New York academy of sciences: Vol. 1087. Violence and exploitation against women and girls (p. 178–205). Blackwell Publishing.

Ryan, G. D., & Lane, S. L. (1997). Integrating theory and method. In G. D. Ryan & S. L. Lane (Eds.), Juvenile sexual offending: Causes, consequences, and correction (pp. 267–321). Jossey-Bass/Wiley.

Safe Sport eReader. (2021, December 14). Erin Willson: The definition of safe sport [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4MWwmMdEEhU

Safe Sport eReader. (2021, December 21). Allison Forsyth: What is complicity? [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0B3qBqVV3aU

Safe Sport eReader. (2021, December 23). Erin Willson: Body image and belittling athletes [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lEX_CXVOxWs

Safe Sport eReader. (2021a, December 6). Camille Berube: An athlete’s perspective on safe sport [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OOr2n6ShqBI

Safe Sport eReader. (2021b, December 6). Danielle Lappage: Attending the AthletesCAN safe sport summit [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HOiB7OUHtuQ

Safe Sport eReader. (2021c, December 6). Neville Wright: An athlete’s perspective on racial discrimination in sport [ Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jUOjLxwPgc8

Safe Sport Training. (n.d.). Retrieved December 30, 2021, from https://safesport.coach.ca/

SIRC. (n.d.). Policies & procedures. Retrieved December 30, 2021, from https://sirc.ca/safesport/policies-practices/

Stirling, A. (2009). Definition and constituents of maltreatment in sport: Establishing a conceptual framework for research practitioners. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 43(14), 1091–1099. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsm.2008.051433

Stirling, A. E., & Kerr, G. A. (2008). Defining and categorizing emotional abuse in sport. European Journal of Sport Science, 8(4), 173–181. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461390802086281

Vertommen, T., Schipper-van Veldhoven, N., Wouters, K., Kampen, J. K., Brackenridge, C. H., Rhind, D. J. ., Neels, K., & Van Den Eede, F. (2016). Interpersonal violence against children in sport in the Netherlands and Belgium. Child Abuse & Neglect, 51, 223–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.10.006

Waldron, J. J., Lynn, Q., & Krane, V. (2011). Duct tape, icy hot & paddles: Narratives of initiation onto US male sport teams. Sport, Education and Society, 16(1), 111-125.

Willson, E., Kerr, G., Stirling, A., & Buono, S. (2021). Prevalence of maltreatment among Canadian National Team athletes. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/08862605211045096

World Health Organization. (2020, June 8). Child maltreatment. Retrieved December 28, 2021, from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/child-maltreatment

- Willson et al., 2021 ↵

- Kerr et al., 2009 ↵

- AthletesCAN, 2019 ↵

- Levenson, 2018 ↵

- Gymnastic Alliance, n.d.; Levenson, 2018 ↵

- Davison, 2021; Ehekircher, 2020; Longman & Brassil, 2021; Muchnick, 2021 ↵

- Ingle, 2021 ↵

- Alexander et al., 2011; Kerr et al., 2019, Parent & Vaillancourt-Morel, 2020; Vertommen et al., 2016 ↵

- Kerr et al., 2019 ↵

- Willson et al., 2021; Vertommen et al., 2016 ↵

- World Health Organization, 2020 ↵

- Adapted from Stirling, 2008 ↵

- Hu & Liu, 2017; Pense & Paymer, 1986; Russo & Pirlott, 2006 ↵

- Allan et al., 2019; Waldron et al., 2011 ↵

- Waldron et al., 2011 ↵

- Kerr et al., 2016 ↵

- Brackenridge, 1994; Burke, 2001 ↵

- Crooks & Wolfe, 2007 ↵

- Alexander et al., 2011; Vertommen et al., 2016; Willson et al., 2021 ↵

- Stirling & Kerr, 2008 ↵

- Kerr et al., 2019 ↵

- Durrant, 2006; Perry et al., 2002 ↵

- Stirling, 2009 ↵

- Kerr et al., 2019 ↵

- Ryan & Lane, 1997 ↵

- Kerr et al., 2019 ↵

- Brittain, 2006 ↵

- Stirling, 2009 ↵

- Kerr et al., 2019 ↵

- Kirby & Greaves, 1996 ↵

- Coaching Association of Canada, n.d. ↵

- Canadian Safe Sport Program, n.d. ↵

- Canadian Safe Sport Program, n.d. ↵

- AthletesCAN, 2020 ↵

- CCES, n.d. ↵

- Dubin, 1990 ↵

- Comeau, 2013 ↵

- Government of Canada, 2017 ↵

- Kerr, et al., 2019 ↵

- AthletesCAN, 2020, p. 19 ↵

Universal Code of Conduct to Address Maltreatment in Sport, promulgated in 2020.

Independent body charged with overseeing operational aspects of the Universal Code of Conduct to Prevent and Address Maltreatment in Sport (UCCMS). In Canada, the SDRCC has been named as the NIM to oversee the UCCMS. A regulatory body with the authority to implement safe sport policies.

Volitional acts that result in or have the potential to result in physical or psychological harm. All types of "physical and/or emotional ill-treatment, sexual abuse, neglect, negligence and commercial or other exploitation, which results in actual or potential harm to health, survival, development or dignity in the context of a relationship of responsibility, trust or power” (World Health Organization, 2010).

Harm that occurs between two actors, with one person having significant influence over another’s sense of security, trust, and/or fulfillment of needs (Crooks & Wolfe, 2007).

Harm that occurs between two actors, with one person having significant influence over another’s sense of security, trust, and/or fulfillment of needs.

Maltreatment between peers.

Maltreatment that occurs outside of a critical relationship. There is typically a power imbalance that occurs between the two actors; however, the perpetrator does not have a direct influence on the others sense of safety or trust.

A pattern of deliberate non-contact behaviours that have the potential to be harmful, including physical and verbal behaviours and denial of attention.

Infliction of physical pain or injury, which can be contact or non-contact behaviors.

Any sexual interaction with person(s) of any age that is perpetrated against the victim’s will, without consent, or in an aggressive, exploitative, coercive, manipulative, or threatening manner (Ryan and Lane, 1997).

The omission of care; failing to enact a duty of care; failing to provide the necessities of life.

In the News:

In the News:

In Practice:

In Practice: