8 Psychoanalysis (SC)

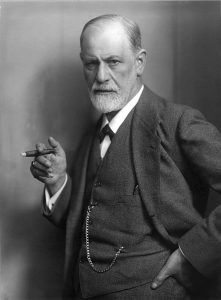

Sigmund Freud (1856-1939) (**SC)

Written by: Mark Pillai

Sigmund Schlomo Freud was a Jewish-Austrian physician most noted for his contributions as the father of psychoanalysis. Freud was born in 1856 in Freiberg in the Austro-Hungarian Empire (today Příbor, Czech Republic). As a medical student at the University of Vienna, Freud specialized in “nervous disorders”, and was initially interested in studying the unconscious mind to understand and resolve mental disorders.

It was the observations of his colleague, Dr. Josef Breuer, which inspired Freud to explore the unconscious mind. Breuer’s patient, Bertha Pappenheim, known famously as Anna O, suffered from episodes of hysteria, hallucinations and personality shifts, which began when she was taking care of her dying father. Anna O coined the term, “talking cure”, for one of Breuer’s chosen therapy techniques, in which he encouraged Anna O to talk about her previous traumas and explored their relation to her current symptoms (Macmillan,1977). By sharing his observations of Anna O and the techniques he employed to help her, with his younger colleague Freud, Breuer triggered the birth of psychoanalysis.

The first psychoanalytic theories postulated by Freud emerged in the late 1880s and early 1890s, while he was working in Vienna. Freud developed his theories through a form of talk therapy called “free association”, in which he allowed his patients to talk about whatever came to mind (Funder, 2019). During the free association task, patients bring their unconscious thoughts and fears into the conscious, where they can reason about them logically (Funder, 2019). Freud also believed that the order in which the patient jumped from one thought to another was non-random, and provided insight into the patient’s unconscious (Funder, 2019). These ideas spur from his theory of the topographic model of the mind.

Freud’s topographic model of the mind theory describes the human mind as having three systems: the conscious, preconscious and unconscious (Boag, 2020). Often this model is compared to an iceberg, where the small, easily accessible conscious is the tip above the water, the preconscious is just under the surface, and the large, hard-to-access unconscious is hidden deep underwater (Funder, 2019). Although the unconscious is hidden and difficult to bring to conscious awareness, it still affects the individual’s thoughts, feelings and behaviours. Therefore, Freud considered it important to analyze his patients’ unconscious minds through free association in order to determine what experiences hidden underneath the surface gave rise to distressing symptoms.

Freud rooted his theory of personality in the conscious and subconscious mind. He believed that every individual had an id, ego and superego, which interact to form the individual’s personality. The id is the part of humans that is primal and selfish, seeking out immediate gratification no matter the circumstance (Psychotherapedia, 2011). The ego fulfills the id’s wishes, but in accordance with society’s rules, while the superego is the moral voice that makes sure that the ego takes into consideration moral rules along with societal ones when fulfilling the id’s wishes (Psychotherapedia, 2011). Further, Freud believed that the individual is only born with the id, while the ego and the superego develop in early life stages, and that psychological disorders were caused by emotional turmoil between the id and superego.

Many of Freud’s developmental theories centred around psycho-sexuality. One of the most infamous theories is the Oedipus complex, invoking the Greek myth of Oedipus, who inadvertently sleeps with his mother and kills his father (Freud, 1961). Freud proposed that sons develop a primary attachment to mothers, thus competing for their mothers’ affection with their fathers. Daughters, on the other hand, were said to suffer from castration anxiety, in which a lack of male genitals is internalized as gendered punishment early on, particularly in patriarchal societies. Given his strong focus on sex, Freud hypothesized that human psychology consists of two primal instincts: libido (sexual energy) and thanatos (death instinct, fight-or-flight).

Presented above are only a few of Freud’s psychoanalytic theories, and he had more that both intrigued and outraged many. Although Freud’s work established him as the “father of psychoanalysis”, the validity of his work is questionable. Freud developed his theories based on case studies, not experimental research. His work is not replicable, meaning none of his theories can be proved nor disproved, and therefore it is not scientific (Funder, 2019). As modern research strives towards scientific significance, Freud can be easily criticized for his methods, however, his work fit the zeitgeist of the times, making him a giant in the psychology field. His adoption of talk therapy acted as a pertinent starting point in shifting psychology from a mechanistic to a holistic understanding.

The Austrian physician became a tenured professor at the University of Vienna in 1902 and gained a large following. His ideas were popularized particularly in the aftermath of WWI, during which a large shell-shocked German-speaking population was hungry for acknowledgement and efficient therapeutic methods. Freud subsequently founded the International Psychoanalytic Association, mentoring other analysts such as his protégé Carl Jung. Having barely escaped the Nazi occupation of Austria, Freud died in London in 1939.

References

Personality psychology – Psychotherapedia. (2011). Psychotherapedia. http://www.unifiedpsychotherapyproject.org/psychotherapedia/index.php/Personality_psychology#cite_note-Carver-8

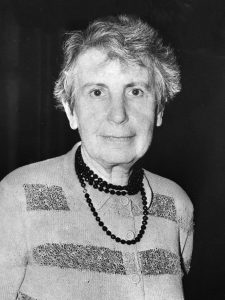

Anna Freud (1895-1982) (**SC)

Written by: Supriya Bains

Anna Freud, termed the “mother of psychoanalysis”, was the youngest child of psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud. Born in Vienna in 1895, Freud grew up greatly admiring her father and his work, but feeling neglected by her mother, Martha (Young-Bruehl, 2008). It was the collection of experiences with her mother, her notice of deficiencies in her schooling and her interest in psychoanalysis that lead Freud to found the field of “child psychoanalysis” (Young-Bruehl, 2008).

Although Freud became a renowned child psychoanalyzer, Young- Bruehl (2008) describes that she did not begin her career as one. Anna’s first job was as a school teacher. Despite her mother’s treatment of Freud being unaffectionate, this did not prevent her from becoming a warm and enthusiastic teacher to her students. However, after getting sick with tuberculosis, she could no longer teach and focused on pursuing psychoanalysis instead. Her father allowed her to join his Secret Committee, filled with his closest collaborators and fellow psychoanalysts, and she even helped found and taught child psychoanalysis at the Vienna Psychoanalytic Institute. Freud believed that child and adult analysis should differ, as the child’s superego (morality) relies on parental influence. Freud also believed in the importance of the psychoanalyst keeping in close touch with the child’s parents, and teaching the child how to apply what was learned in therapy to daily life (Young-Bruehl, 2008).

By applying her father’s idea of using direct observation to complement the psychoanalysis of children, Freud opened a nursery for young children in Vienna in 1937 (Young-Bruehl, 2008). She and the researchers working there took careful notes on the behaviours of the children, such as how they ate and how they played (Young-Bruehl, 2008). Unfortunately, under the threat of a Nazi invasion of Austria, Freud had to flee to London with her family (Young-Bruehl, 2008). As WWII broke out, Anna opened the “Hampstead War Nurseries” in 1941 to help children affected by the war. This was another one of Freud’s “natural experiments”, where while observing and researching the children, she also aimed to prevent further mental harm to the children caused by the war and repair any damage that already occurred (Midgley, 2007). The findings of Freud and her staff revealed the harmful effects of war on children. Freud discovered the dangers of broken parental attachments, the importance of strong relationships with new caretakers, and the idea that paternal relationships are just as important as maternal ones (Midgley, 2007).

Freud’s pioneering work in the nurseries allowed for the development of effective treatments for children and set the foundations for the field of child psychology. Anna Freud’s work contributed to the fields of psychology, education, social work, sociology, and human ecology. By working in a time when women in academia faced great adversity, Freud proved that women are able to pave their own path in psychology.

References

Aldridge, J., Kilgo, J.L., & Jepkemboi, G. (2014). Four hidden matriarchs of psychoanalysis: the relationship of Lou von Salome, Karen Horney, Sabina Spielrein and Anna Freud to Sigmund Freud. International Journal of Psychology and Counselling, 6(4), 32-39. https://doi.org/10.5897/IJPC2014.0250

Midgley, N. (2007). Anna Freud: The Hampstead War Nurseries and the role of the direct observation of children for psychoanalysis. The International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 88(4), 939-959.

Young-Bruehl, E. (2008). Anna freud : A biography, second edition. Yale University Press.

Girindrasekhar Bose (1887–1953) and Indian Psychotherapy

Girindrasekhar Bose was an Indian physician and psychiatrist who pioneered psychoanalysis in India in the early 20th century.

According to Ramana (1964), Bose was born in Darbhanga, India, and grew up the youngest son of a large family. He earned his medical degree at the University of Calcutta in 1910. While working as a physician, Bose’s interest in the psychological problems of his patients incentivized him to earn his Master’s in experimental psychology. However, Bose remained curious about human behaviour and began using different methods with his patients to study it, such as “hypnotism, free associations, and introspection” (Ramana, 1964, p. 112). Due to the little exposure Indian society had to Freud, it is likely Bose constructed his psychoanalytic ideas almost entirely separate from the influence of Freud (Harding, 2009).

Ramana (1964) states that Bose conveyed his theories in the thesis, The Concept of Repression, for which he earned the first Doctorate of Science in Psychology in India in 1921, and became a lecturer at the University of Calcutta. He published the book Concept of Repression that same year and sent it to Sigmund Freud, thus initiating their ongoing correspondence. Bose also began communicating with Ernest Jones, and deliberated with Jones and Freud before establishing the Indian Psychoanalytical Society in 1922, making it the first psychoanalytical society in a non-Western country. Soon after, the Society was accepted as a branch of the International Psychoanalytical Association, and Bose remained its president until his death (Ramana, 1964).

Bose’s psychoanalytical theory was heavily influenced by the principles of Hinduism. As Ramana (1964) presents Bose’s correspondence with Freud, it is clear that Bose’s views differed from his European contemporaries. Instead of holding a dualistic view, whereby individuals stand in conflict with external objects and internal impulses, Bose believed that individuals were capable of uniting with the outer world. Thus, he contended that psychopathology results not from a conflict between “self” and “other”, but from a conflict between repressing and repressed wishes. He believed that Indian and European patients possessed different psychological traits, and as such, Indian philosophy could provide potentially universally relevant insights into the mind. Thus, he formulated the theory of opposite wishes, which states that every wish/desire must have a counterpart in the unconscious. The conflict between the two opposing wishes results in tension, which can be resolved by identifying with the repressed wish. Bose provided an example of this theory in action when he described a male patient suffering from impotence, who he believed had an unconscious wish to be female. He conceptualized that this wish existed as a result of early identification with their mother. He proposed that imagining the fulfilment of the wish was an unconscious strategy to reduce the anxiety caused by its repression. Through repetitively alternating between imagining one as a female with female sexual desires and as a male with male sexual desires, the clients’ impotence was resolved. This concept reflects the ideas of projection and intersubjectivity, which had yet to be fully developed in Western psychoanalytic theory.

Bose spearheaded the psychoanalytic movement in India and demonstrated highly sophisticated theorizing based almost entirely on his own clinical experiences as well as his religious and spiritual background.

The Development of Psychoanalysis in India

According to Hartnack (1990), psychoanalysis in India started with the work of Girindrasekhar Bose in the early 1920s. Following the formation of the Indian Psychoanalytical Society in 1922, discussions of psychoanalysis became increasingly popular among the Western-educated physicians and psychologists working in Calcutta. As a result, the Indian Psychoanalytical Institute was formed in 1930 with the objective of practicing psychoanalytic psychotherapy (carried out by medical doctors) and lay analysis (carried out by psychologists). In addition, the Indian Psychoanalytical Society headed an outpatient psychiatric clinic at the Carmichael Medical College and Hospital in 1933. By 1940, the Institute had established the country’s first inpatient psychiatric facility, and the Society began producing its official journal, Samiksa Analysis, in English (Hartnack, 1990). Over the next two decades, Chitta, a Bengali psychoanalytical journal, and Bodhayana, a residential nursery school for children with emotional and behavioural problems, were also established (Ramana, 1964). Two psychiatrists who were among those trained by Bose were Tarun Sinha and C. V. Ramana, who both served as presidents of the Indian Psychoanalytical Society after Bose’s death (Ramana, 1964).

Hartnack (1990) emphasizes the importance of considering the imprint of Indian culture and British colonization in Indian psychoanalysis. Unfortunately, Owen Berkeley-Hill and Claude Dangar Daly, officers of the British army and two of the original 15 members of the Indian Psychoanalytical Society, used psychoanalysis to degrade and further oppress the Hindu identity. Their “studies” reflected the ideology of the British agenda in colonial India, and served as a means to maintain their “cultural superiority”. Indeed, Bose’s correspondence with Freud revealed his concerns about the psychoanalytic value of Berkeley-Hill’s writings. Furthermore, only these British members of the Society were able to publish several articles in the International Journal of Psychoanalysis and attend some of the International Psychoanalytical Association’s conferences. Thus, they helped exchange ideas between Europe and India, but as the sole representatives of Indian psychoanalysts. Furthermore, after India’s independence from Britain in 1947, psychoanalysis diminished significantly as a result of extreme poverty. The surge of mental illness as a result of this poverty was immense, and the resources to treat them were limited. Moreover, physiological and safety needs became the priority for resource distribution, and thus the rapid development of psychoanalysis in India was impeded. However, there did remain some interest in psychoanalysis in various regions of the country. These incidences demonstrate some of the cultural and socio-political influences on the potential development of academic and clinical fields in non-Western countries (Hartnack, 1990).

References

Akhtar, S. (2008). Psychoanalysis in India. Freud along the Ganges (pp. 3–25). Stanza.

Harding, C. (2009). Sigmund’s Asian fan club?: The Freud franchise and independence of mind in India and Japan. Newcastle-upon-Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Press.

Hartnack, C. (1990). Vishnu on Freud’s desk: Psychoanalysis in colonial India. Social Research, 57, 921–949. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40970621

Ramana, C. (1964). On the early history and development of psychoanalysis in India. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 12, 110–134. https://doi.org/10.1177/000306516401200107

Contributors

- Harshdeep Dhaliwal

- Shanur Syed

- Parham Seyedmazhari

Heisaku Kosawa (1897-1968) and Japanese Psychotherapy

The Beginnings of Japanese Psychotherapy

Blowers and Yang Hsueh Chi (1997) date the beginnings of psychoanalysis in Japan to 1912, with the publications of “The Psychology of Forgetting” by Ohtsuki Kaison (considered the first Japanese article on psychoanalysis) and “How to Detect the Secrets of the Mind and to Discover Repression” by Kyuichi Kimura. The first Japanese psychoanalytic book, Study of Sexuality and Psychoanalysis, was published in 1919, written by Sakaki Yasusaburo.

Okonogi (2004) credits Marui Kiyoyasu, a Japanese psychiatrist, with playing a large role in introducing psychoanalysis as a treatment for psychiatric disorders to the field of Japanese psychiatry*. After completing his studies in neurology at John Hopkins University and being exposed to American psychoanalysis, Kiyoyasu returned to teach psychoanalysis to the medical students of Tohoku University. The students who studied under Marui became the first generation of Japanese psychoanalysts and are commonly known as the Tohoku School (Okinohi, 2004). Marui also taught psychoanalytic theory to practicing Japanese psychiatrists starting in 1925 published several psychoanalytically-oriented psychiatric textbooks, and established a Sendai (northern Japan) branch of the International Psychoanalytical Association (Harding, 2014).

Heisaku Kosawa

Blowers and Yang Hsueh Chi (1997) describe how one of Marui’s students, Heisaku Kosawa, was dissatisfied with the lack of a psychoanalytically-derived therapeutic practice in Japan. In 1932, he travelled to Austria, where he received psychoanalytic training at the Vienna Psychoanalytic Institute. There, he received a training analysis and individual psychotherapy supervision, and shared his paper, “Two Kinds of Guilt” with Freud upon meeting him. In this paper, Kosawa describes a Japanese variant of the Oedipus complex called the “Ajase” complex.** Unfortunately, Kosawa’s paper was not well-received by Sigmund Freud, which was evidenced by his curt language in their correspondence. Nevertheless, Kosawa returned to Japan and opened his own psychoanalytic clinic in 1933 (Blowers & Yang Hsueh Chi, 1997).

After WWII, the influence of American dynamic psychiatry encouraged many psychologists to study under Kosawa. These students became the second generation of Japanese psychoanalysts known as the Kosawa school (Okonogi, 2004). In 1949, Kosawa formed the Society for Psychoanalytical Studies. This later developed into the Japanese Psychoanalytical Society, comprising of medically trained psychiatrists. Moreover, Kosawa took over the Sendai branch of the International Psychoanalytical Association in 1953, changing its name to the Japan branch and relocating it to Tokyo (Okonogi, 2004). Psychoanalysis continued to gain popularity in Japan throughout the 1960s and 1970s, with a surge of interest in the clinical practice of psychoanalytic psychotherapy.

*Marui Kiyoyasu went to John Hopkins around 1918–1919; the exact date of his return is debated.

**For more information about the Ajase Complex, refer to Blowers & Yang Hsueh Chi, 1997.

The Role of Buddhism in Kosawa Psychoanalysis

Christopher Harding’s “Japanese psychoanalysis and Buddhism: the making of a relationship” analyses the connections to Buddhist philosophy in the 20th-century Japanese psychoanalysis of Kosawa Heisaku (1897–1968). Having travelled to Vienna to study psychoanalytic practice with Freud and his colleagues in 1932, Kosawa recognized the psychological differences between Japanese and Western society. For instance, Western societies are more typically focused on independence, whereas Japanese culture places emphasis on collectivism. Thus, he believed that in order for Japanese people to undergo proper psychoanalysis, they would require a Japanese analyst. With this in mind, Kosawa opened a private practice in Tokyo after returning from Vienna in 1933, and saw as many as 400 patients in its first three years of operation. Although Kosawa’s published works rarely contained a discussion of the relationship between his psychoanalysis and its religious influences, the effect of Buddhist philosophy, particularly the Jōdo Shinshū tradition, on his life and work has been cited by Kosawa’s colleagues, friends, and clients. The subtlety of Kosawa’s connections between psychoanalysis and Buddhism stemmed from his belief that they are merely two different conceptualizations of the pursuit of well-being, rather than completely separate approaches to life (Harding, 2014).

Harding (2014) further describes how the Jōdo Shinshū tradition was founded by Shinran (1173–1263), originally a Tendai Buddhist, who adopted the Pure Land tradition of Mahayana Buddhism. Shinran subsequently distinguished between jiriki and tariki, which referred to the methods of how one pursued salvation. Jiriki means one’s own ability to bring about salvation, while tariki means the power of the ‘Other’, represented by the celestial Buddha Amida, to affect one’s salvation. In the Jōdo Shinshū tradition, there was an emphasis placed on tariki, while an overindulgence in jiriki was generally frowned upon. With regard to the incorporation of these practices into Kosawa’s psychoanalytic theory, his main focus was on sange, which referred to the experience of understanding oneself completely after sensing the power of the ‘Other’. This sensation was thought to be brought about by the act of showing remorse and being met with unconditional acceptance from a familiar person (Harding, 2014).

The integration of religion into psychoanalytic theory and practice was a point of differentiation between the psychoanalysis of Kosawa and Freud (Harding, 2014). For example, the concept of sange was evident in Kosawa’s Ajase complex, whereas it was ignored in Freud’s Oedipus complex. Kosawa also believed that in order to achieve a new sense of self, which he attributed as the primary goal of psychoanalysis, one must undergo a religious experience analogous to that of shinjin, or ‘true entrusting’ (‘enlightenment’ in Zen Buddhism), while Freud rejected religion outright in his discipline (Harding, 2014). Although Kosawa’s school of psychoanalysts has moved away from the inclusion of Buddhist philosophy in the practice of psychoanalysis, investigations of his discipline yield important considerations for the development of religious-psychological practices, which have been gaining prominence in modern-day Japan (Harding, 2014).

References

Blowers, G. H. & Yang Hsueh Chi, S. (1997). Freud’s deshi: The coming of psychoanalysis to Japan. Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences, 33, 115–126. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1520-6696(199721)33:2<115::aid-jhbs1>3.0.co;2-s.

Harding, C. (2014). Japanese psychoanalysis and Buddhism: The making of a relationship. History of Psychiatry, 25, 154–170. doi:10.1177/0957154×14524307

Huntington, R. M. (1968). Comparison of Western and Japanese Cultures. Monumenta Nipponica, 23(3/4), 475–484. https://doi.org/10.2307/2383501

Okonogi, K. (2004). A history of psychoanalysis in Japan. In Kitayama, O. (Ed.) Japanese contributions to psychoanalysis. Japan Psychoanalytic Society.

Contributors

- Christian Kleiser

- M. Grant Leger

- Emilia Flores Anaya

Yaekicki Yabe (1875–1945)

Yaekicki Yabe helped introduce “lay analysis”, or psychoanalysis administered by a non-physician, to Japan.

Blowers and Yang Hsueh Chi (1997) describe how Yabe studied psychology both in the United States and Europe. While in Germany, he received his psychoanalytic training and obtained his analyst certificate in 1930. When he returned to Japan, he began practicing psychoanalytic psychotherapy. Yabe and Ohtsuki Kenji, a literature graduate, established the Tokyo Psychoanalytical Association, which was made up of lay analysts (psychology and literature graduates). In addition, Ohtsuki formed the Tokyo Institute of Psychoanalysis with the objective of translating all of Freud’s works from English into Japanese.

References

Blowers, G. H. & Yang Hsueh Chi, S. (1997). Freud’s deshi: The coming of psychoanalysis to Japan. Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences, 33, 115–126. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1520-6696(199721)33:2<115::aid-jhbs1>3.0.co;2-s.

Doi, T. & Schwaber, E. A. (2016) Chapter 1: Psychoanalysis and the Japanese personality, Chapter 2: Psychoanalysis and Western Man, Chapter 3: Amae and Transference-Love, Chapter 4: Heeding the Vocabulary of Another Culture: Psychoanalysis in Japan. Psychoanalytic Inquiry, 36, 171–186, https://doi.org/10.1080/07351690.2015.1124001

Okonogi, K. (2004). A history of psychoanalysis in Japan. In Kitayama, O. (Ed.) Japanese contributions to psychoanalysis. Japan Psychoanalytic Society.

Contributors

- Christian Kleiser

Takeo Doi (1920–2009)

Takeo Doi, a Japanese psychiatrist, was a member of the Kosawa school and served as the president of the Japanese Psychoanalytical Society. Doi is most renowned for his contribution of the concept of “amae”, which was the first, and most influential, culturally derived psychoanalytical theory in Japan. He first introduced this concept in 1956 in the paper “Japanese Language as an Expression of Japanese Psychology”. According to Doi (1992), the concept of “amae” combines the feeling of dependence and the observable behaviour of attachment. The most common example of amae is when an infant begins to recognize and seek closeness with the mother. However, amae is also present in intimate adult relationships. Moreover, amae is always conveyed non-verbally, and thus, it can occur with or without the awareness that it is occurring. Psychological dependence is intrinsic to amae because individuals who wish to express amae require another person who is sensitive and responsive to their needs. When reciprocated, amae is a fulfilling and joyful experience. Therefore, a desire for amae that is not met can result in frustration, and in extreme cases, psychopathology.

Doi contended that although the concept of amae has its origins in the Japanese language, the experience of dependency and attachment is not unique to the Japanese. However, given the importance of dependence and interrelatedness in Japanese culture, amae is much more culturally relevant in Japan than in Western societies. Doi (2016) explained how this might be one reason for the relative unpopularity of psychoanalysis in Japan compared to some Western countries, such as the United States (Doi & Schwaber, 2016). One ideal of Western psychoanalytic psychotherapy is that the analyst must remain somewhat detached from the patient. However, for both Japanese psychoanalysts as well as Japanese patients, this poses a challenge to the typical psychoanalytical approach, as close connections between psychotherapist and client are important to the Japanese method. He also established that the types of neuroses commonly observed in Japanese patients are not the same as those viewed in Western patients. For example, aggressive impulses only cause dysfunction when there is a rigid ego boundary between the self and the other. Since dependency is frowned upon in Western cultures, ego defensive mechanisms are commonly the first target of psychoanalytic psychotherapy in the West. In Japan, the boundaries between the self and other are less rigidly established. In summary, the concept of amae elegantly reflects collectivism, a key aspect of the Japanese psyche, and poses important considerations for how psychoanalytical theory should be applied to this population (Doi & Schwaber, 2016).

References

Doi, T. (1992). On the concept of amae. Infant Mental Health Journal, 13, 7–11. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0355(199221)13:1<7::AID-IMHJ2280130103>3.0.CO;2-E

Doi, T. & Schwaber, E. A. (2016) Chapter 1: Psychoanalysis and the Japanese personality, Chapter 2: Psychoanalysis and Western Man, Chapter 3: Amae and Transference-Love, Chapter 4: Heeding the Vocabulary of Another Culture: Psychoanalysis in Japan. Psychoanalytic Inquiry, 36, 171–186, https://doi.org/10.1080/07351690.2015.1124001

Contributors

- Christian Kleiser

The Development of Psychoanalysis in China (SC**)

Written by: Sorina Andrei

In their 2020 paper, “The history of psychoanalysis in China”, Huang and Kirsner provide a rich description of the history and development of psychoanalysis in China.

Psychoanalysis appeared in China following the introduction of Western medicine, with literature on psychoanalysis being translated into Chinese during the early 1900s. The translated works covered the popular topics of the times, such as free association and Freud’s dream analysis. Although the sexual aspects of dream analysis were altered or removed from translations, Freud’s ideas were of great interest during this time of political and cultural change in China. The study and education of psychoanalysis continued to grow in China during the 1930s through the contributions of Bingham Dai, China’s first psychoanalyst. After studying under American psychoanalysts, Dai taught psychotherapy at the Peking Union Medical College where he integrated Neo-Freudian and Confucianism schools of thought to develop psychoanalysis beyond the original Freudian theory. Before 1949, psychoanalysis had a small but respectable start in China, until the progression of the field came to a halt over the next thirty years.

The initial interest in psychoanalysis in China faded as the political climate changed, and war broke through the country. With the establishment of communism in China and the founding of the People’s Republic, anti-Western sentiment became the cultural norm and Western ideologies were rejected. Psychoanalysis was belittled, “due to its Western origins and “idealist” dispositions”. Instead, the focus shifted to neuropsychiatric models from the Soviet Union, such as Pavlovian conditioning. Only a small amount of professionals were permitted to administer and experiment with psychotherapy. This was a method to battle neurasthenia, or “nervous breakdowns”, the most prevalent mental disorder in the country at the time. However, all progress in the psychological field came to a halt during the rise of the Cultural Revolution and the ruling of Chairman Mao (1966–1976). Psychology was seen as a pseudoscience, and the dismantling of the discipline by the government resulted in the closure of psychology programs in universities and hospitals.

Following the death of Chairman Mao and the progression of new political reform in the 1980s, Western ideas were once again being slowly explored. Psychology was reintroduced and again continued developing in the country. Although mental health was still not considered to be a priority in the health system at this time, psychology became a topic of interest in cultural and social debates. A “Freud fever” broke out as an influx of Western literature became translated and previously translated Freudian works were republished. Tseng Wen-Shing, a Taiwanese psychiatrist, advocated for the use of psychoanalysis in psychopathology and highlighted the need to adapt the practice to better support the culture-specific needs in China. Despite the interest in psychoanalysis as a theory, psychoanalysis was not employed in clinical practice, as clinicians were oriented toward behavioural modification.

As China’s economy recovered and the country established itself as a global leader, the population became even more interested in Western products and ideas. During the 2000s, a phenomenon known as the “psycho-boom” occurred, and psychotherapy once again gained popular interest. As mental health became a more recognized issue, government funding and legislation helped develop psychology training, treatment and research in the country. During this time, a new certification was established for psychological counsellors. This certification allowed psychotherapy to become its own profession, rather than remain a small sub-practice of psychologists and psychiatrists.

Currently, psychotherapists in China have their own private practices, and more of the Chinese population seeks out their services than ever before. Psychotherapists are also moving to digital platforms to help their clients, and apps are created to help match individuals to a therapist. Psychoanalysis is now an exciting, growing field in China, which prevailed despite the country’s ever-changing climate over the past century.

References

Huang, H.-Y., & Kirsner, D. (2020). The history of psychoanalysis in China. Psychoanalytic Inquiry, 40(1), 3–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/07351690.2020.1690876

Comparative Psychoanalysis: Cultural Differences Between Eastern and Western Society

In the paper “Psychoanalysis in India and Japan: Toward a Comparative Psychoanalysis”, Alan Roland identifies some key differences between the theory and practice of psychoanalysis in Eastern and Western societies. Roland asserts that the components of psychoanalytic theory are universal, however, the manifestation of these components in different societies varies based on societal and cultural norms. As psychoanalytic theories apply to individuals from various cultures differently, psychotherapy across different cultures and societies differs, often with a number of culturally-informed nuances. One of the broadest divides in cultural psychoanalysis between Western and Eastern societies.

First, the concept of ego is different between Eastern and Western cultures. Individuals from Western societies tend to have more rigid outer ego boundaries between the “self” and the “other”, compared to individuals from Eastern societies. However, within these two groupings, further differences exist, such as between the two Eastern Indian and Japanese cultures. Roland suggests that Indian and Japanese individuals have a unique kind of ego boundary which allows them to contain private thoughts and feelings while sharing psychological space with others. Roland suggests that Indians are more in tune with their inner feelings and thoughts than Western cultures, whereas Japanese individuals are less in tune with their inner self compared to Western cultures.*

Next, though psychosocial development universally consists of distinct stages, these stages vary between cultures. In Western psychoanalytic theories, the stages of psychosocial development are typically as follows: separation-individual, autonomy, independence, and initiative in early childhood, and identity conflicts and resolutions in adolescence. In India and Japan, however, there is an emphasis on the development of dependence and interdependence early in childhood, which promotes the adaptive functioning of the child in groups and large family units. Moreover, there appears to be a lack of identity conflicts among Indian and Japanese adolescents.

Perhaps most relevant to the practice of psychoanalytic psychotherapy, the social structures and expectations of Eastern and Western cultures significantly impact the needs and functions of the relationship between patient and psychoanalyst. In Western cultures, the psychoanalytic relationship assumes equality between analyst and patient, respect of each other’s autonomy, and predetermined responsibilities. On the other hand, Indian and Japanese cultures emphasize reciprocal obligations between individuals situated in a structural hierarchy and emotional interconnectedness. Thus, the expectations of the psychoanalytic relationship are that they follow proper social etiquette and that they are formed on the basis of dependency and empathy.**

Finally, with regard to how psychoanalysts theorize in various countries, Western psychoanalysts often universalize the components of psychoanalysis, whereas Eastern psychoanalysts contextualize these same components. Moreover, Western psychoanalytic theories are heavily focused on dualistic relationships (e.g., between the self and the other), while Indian psychoanalytic theories view everything on a continuum.

These observations demonstrate the universality of psychoanalysis and the extent to which it can be applied to various cultures, so long as due consideration is given to the implications of those cultures.

*Based on the author’s clinical experiences.

**For a more in-depth description of the cultural nuances of psychoanalytic psychotherapy, see Roland, 1991.

References

Roland, A. (1991). Psychoanalysis in India and Japan: Toward a comparative psychoanalysis. The American Journal of Psychoanalysis, 51, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf01250266

Contributors

- Anmol Thind