16 Evolutionary Psychology

Sociobiology

Sociobiology is the study of the evolution of social behaviour.

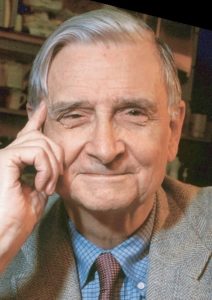

E. O. Wilson (1929- 2021)

E.O. Wilson was an American biologist who popularized the theory of sociobiology.

Edward Osborne Wilson was born in Birmingham, Alabama, and spent most of his childhood outdoors (E.O. Wilson, 2015). He was highly interested in insects, particularly ants. This interest did not die out, and after receiving his Ph.D. from Harvard University in 1955, Wilson began his fieldwork studying ants around the world. Throughout his career, he published several important works for the fields of ecology and biology, such as The Theory of Island Biogeography (1967)* and Biophilia (1984). However, one of his most important works is Sociobiology: The New Synthesis (1975)**, which caused a major stir in the scientific community.

In this work, Wilson argued that there are biological foundations to human social behaviour, and provides an evolutionary perspective on this topic (Driscoll, 2013). Wilson states that rather than social behaviour being solely the result of psychological, individual differences, evolution drives the differences in animal populations through genes. This work has been criticized by many in the scientific community, as they believed he provided an argument for poor social behaviour.

References

Driscoll, C. (2013). Sociobiology (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy). Stanford.edu. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/sociobiology/

E.O. Wilson Biodiversity Foundation» E.O. Wilson. (2015). Eowilsonfoundation.org. https://eowilsonfoundation.org/e-o-wilson/

Further Reading

*Macarthur, R. H., & Edward Osborne Wilson. (1967). The theory of island biogeography. Princeton University Press, Tr.

**Wilson, E. O. (1975). Sociobiology : the new synthesis. Belknap Press Of Harvard University Press.

***Wilson, E. O. (1984). Biophilia. Harvard University Press.

Richard Dawkins and the “Selfish Gene”

Richard Dawkins is an Oxford alumnus and a British evolutionary biologist. His book, The Selfish Gene (1976), expanded upon George C. Williams’ Adaptation and Natural Selection (1966). This book became a best-seller, as it changed perspectives in science and reached the general public as well.

In The Selfish Gene, Dawkins states that genes are the unit for evolution and that genes are “selfish”. Building on Darwin’s argument that organisms are the ones that are being selected for in natural selection, Dawkins instead claimed that it is not just the organisms being selected for, it is the organism’s genes (Ridley, 2016). Organisms, he states, are simply vehicles for genes to propagate themselves into the next generation. Therefore, certain genes have survived over the course of millions of years because they have been evolutionarily advantageous for the organism, leading to its survival and reproduction. Although the organism will die out over generations, the gene will survive and evolve.

Dawkins used this theory to explain altruistic behaviour, or selflessness (Ridley, 2016; The Selfish Gene Summary, n.d.). Earlier evolutionary biologists believed that selfless behaviour in nature was due to the organism wanting to protect itself or its species. For example, a bee will sting an intruder in the hive at the cost of death. Earlier biologists might have believed that the bee wanted to protect its hive mates, however, Dawkins would argue that the bee is protecting its genes, found in its relatives. Since closely related organisms share more genes, they are likelier to behave altruistically.

Dawkins applies this theory to humans. Similar to the gene, a unit of evolution, the “meme” is the unit of cultural transmission (Dawkins & Davis, 2017). The meme is formed in an individual’s mind, and further propagated by the exchange of ideas by humans. The meme is transmitted through generations and affects human fitness.

References

Dawkins, R., & Davis, N. (2017). The selfish gene. Macat Library.

Ridley, M. (2016). In retrospect: The Selfish Gene. Nature, 529(7587), 462–463. https://doi.org/10.1038/529462a

The Selfish Gene Summary and Study Guide (n.d.). SuperSummary. Retrieved from https://www.supersummary.com/the-selfish-gene/summary/

Further Reading

Dawkins, R.C. (1976). The selfish gene. Oxford University Press.

Francis Galton’s Eugenics

In the 20th century, eugenics had a widespread and enduring impact on individuals and societies. Eugenics was highly influential in the development of psychological theories, research practices, and beliefs about mental illness in British and American psychology (Yakushko, 2019). The term eugenics was created by Francis Galton, who drew inspiration from social Darwinism, theories related to the evolution of human societies; and Malthusianism, the idea that social problems result from the disproportionate growth of the lower-class population compared to that of the upper class. The eugenics movement impacted both the scientific as well as the broader social contexts. With regard to scientific disciplines, eugenics was the foundation from which scientific racism and sexism were cultivated, which led to marginalized groups being treated as genetically inferior in the context of scientific research. Outside of the scientific realm, eugenics provided purportedly empirical evidence to sustain the belief that marginalized groups were inferior. Moreover, eugenic research influenced government decisions in the West, including those involved in segregated schooling, the expansion of large-scale asylums, immigration regulations, etc. Therefore, it is clear that eugenics was not simply an isolated field of psychology, but that it had wide-ranging impacts on how people were perceived and treated within society (Yakushko, 2019).

In addition to pursuing the scientific investigation of varied groups within society, eugenicists also sought to promote the social evolution of humans through “positive” and “negative” eugenic methods (Yakushko, 2019). Positive eugenics refers to the arrangement of marriages between eminent men and women, while negative eugenics refers to the restriction of unfit individuals from procreation, carried out with methods such as involuntary sterilization. Women and adolescent girls made up the majority of involuntary sterilizations in the 20th century, particularly women of colour and women whose “sexual purity had been compromised”. Moreover, eugenicists asserted that physical and mental disorders, particularly those present in marginalized and lower-class populations, should not be treated in order to prevent evolutionarily unfit individuals from passing on maladaptive genes. They contended that by following these methods, rates of physical and mental illness, as well as poverty, would decline in the human population. Numerous studies were conducted throughout the first half of the 20th century to promote negative eugenics. One such study conducted by Henry H. Goddard, in which he determined that the procreation of a fit man with an unfit woman resulted in a mental deficiency several generations later, was used as a foundation for the development of Nazi campaigns (Goddard, 1912; Yakushko, 2019).

Eugenics in Europe

One of the most devastating effects of eugenics happened in Europe during the Second World War, the Holocaust (Grodin, Miller & Kelly, 2018). Taking inspiration from the eugenics programs in the US, Fascist leader of the Nazi party, Adolf Hitler, and Nazi physicians set out to exterminate “undesirable” members of society. Those who belonged to this group included Jews, homosexuals, Romani and the disabled. This extermination was justified as a method to “improve public health” and prevent the “contamination” of the German population. The beginnings of this extermination occurred in the early 1930s when a law was passed calling for the sterilization of mentally and physically disabled individuals. This progressed into euthanasia (“mercy killing”) of disabled adults and children, in the interest of lessening the burden they have on society and purifying the Aryan race. Eventually, killing centres were created for disabled individuals, where they were murdered in gas chambers. Soon after, the mass killings of “enemies of the German state” began in concentration camps around Europe.

Eugenics in America

Despite the extent of injustice caused by this movement, eugenics was extremely pervasive in American psychology, with the production of many articles, books, and journals devoted to eugenic research, and the establishment of several eugenic organizations (Yakushko, 2019). Between 1892 and 1947, 31 APA presidents were members and/or leaders of eugenic organizations, including G. Stanley Hall, Edward L. Thorndike, Robert S. Woodworth, John B. Watson, Robert Yerkes, and Lewis Terman. In addition to those publicly listed as members of these institutions, a number of other prominent psychologists promoted eugenics in their publications, including Karl Pearson, William McDougall, Hans Eysenck, James McKeen Cattell, James Mark Baldwin, Hugo Munsterberg, Joseph Jastrow, James Rowland Angell, and Margaret Floy Washburn. Given the range of psychological perspectives adopted by these psychologists throughout the 20th century, it is essential to recognize the extensive impact of eugenics on the development of psychology during this time (Yakushko, 2019).

References

Grodin, M. A., Miller, E. L., & Kelly, J. I. (2018). The Nazi Physicians as Leaders in Eugenics and “Euthanasia”: Lessons for Today. American Journal of Public Health, 108(1), 53–57. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2017.304120

Yakushko, O. (2019). Eugenics and its evolution in the history of western psychology: A critical archival review. Psychotherapy and Politics International, 17. https://doi.org/10/gg3hsf

Further Reading

Crump, M. (2020). Psychology and Eugenics connections. Crumplab.github.io. https://crumplab.github.io/blogposts/7_13_20_PsychEugenics/7_13_20_PsychEugenics.html#1929_karl_lashley

Goddard, H. H. (1912). The Kallikak Family. Macmillan Company.

Kevles, D. J. (1999). Eugenics and human rights. BMJ, 319(7207), 435–438. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.319.7207.435

Mukherjee, S. (2017). The Gene: An intimate history. Scribner.

Contributors

- Emilia Flores Anaya

- M. Grant Leger

- Anmol Thind

Criticisms and Controversies

This section is currently under construction.