26 Perception Neuroscience

Ernst Heinrich Weber (1795-1878)

Weber’s Compass

Ernst Heinrich Weber designed the“Weber’s compass” to measure tactile discrimination in different regions of the body (Dias, 2006). The use of Weber’s compass appeared in anthropological studies at the end of the 19th century, namely Paul Hyades’ expedition to Cape Horn and William McDougall’s expedition to the Torres Strait. In each of these expeditions, Hyades and McDougall utilized the compass to measure tactile discrimination among the Yahgan people and the Murray Islanders, respectively. By using this instrument, the anthropologists compared the differences in tactile discrimination between sexes and ethnic groups, given that Weber obtained average measurements based on European men as his norm. Both Hyades and McDougall reported that the Yahgan people and the men of Murray Island had greater tactile discrimination than Europeans. It is important to note that Hyades only tested four subjects, did not control for sex differences, measured a different number of body regions across subjects, and did not provide clear explanations of his methodology. In contrast, McDougall tested a larger sample size, focused on two body regions, and tested European subjects for his comparison as opposed to relying on Weber’s averages. While the results of both studies, but particularly Hyades’, should be observed critically, these initial investigations emphasized the importance of considering social, ethnic, and cultural differences when informing conclusions in psychological research.

References

Dias, N. (2006). Eyes shut and hands at work: notes on the use of Weber’s compass in nineteenth century anthropology. History of Anthropology, 33, 3–8.

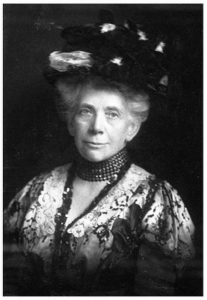

Christine Ladd-Franklin (1847-1930)

Christine Ladd-Franklin was an American mathematician, logician, and psychologist in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, who greatly contributed to the field of colour vision.

Ladd-Franklin grew up in a time when women’s roles in America were restricted to the realms of home and family, and striving for a career in academia would require traversing these societal boundaries (Furumoto, 1992). However, her mother and aunt, who were women rights activists, exposed her to the idea of women’s equality. Ladd-Franklin’s father also supported her education and academic accomplishments. She went on to complete her bachelor’s at Vassar College, where she studied under Maria Mitchell, Professor of Astronomy at Vassar, who made an effort to encourage women to pursue careers in science. These early (and ongoing) influences instilled in Ladd-Franklin the possibility of breaking free from conventional gender roles. After graduating in 1869, Ladd-Franklin taught in high schools until 1878, when she pursued graduate studies at John Hopkins University in mathematics and logic. Ladd-Franklin, who was an exception to the university’s policy of not admitting women as students, was denied the title of fellow even though she met the same criteria for fellowship as her male peers, and was not awarded a Ph.D. at the completion of her work.

Shortly after her time at John Hopkins, she began studying colour vision, the subject matter that awards Ladd-Franklin the designation of a scientific psychologist (Furumoto, 1992). In a paper published in 1893, Ladd-Franklin pointed out the shortcomings of two current theories of colour vision, the Hering and the Young-Helmholtz theories, and presented a new theory that accounted for these faults (Franklin, 1893). Over the next 30 years, Ladd-Franklin continued to develop her theory while publishing her findings. Her “development theory of colour” postulated that throughout evolution, black and white vision evolved first, followed by blue and yellow, and red and green (Ladd-Franklin, 1922; “Review“ , 1929). She goes on to describe how this theory of development explains various phenomena in colour vision, such as the various forms of colour blindness (Tietz, 2020).

Despite the difficulty to be accepted into the inner circles of American psychology, Ladd-Franklin’s research on vision and colour theory was significantly influential in the field of scientific psychology.

References

Furumoto, L. (1992). Joining separate spheres: Christine Ladd-Franklin, woman-scientist (1847–1930). American Psychologist, 47, 175–182. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.47.2.175

Ladd-Franklin, C. (1893). A new theory of light sensation. Science, 18–19. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.ns-22.545.18

Ladd-Franklin, C. (1922). Tetrachromatic vision and the development theory of colour. Science, 55, 555–560. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.55.1430.555

Tietz, T. (2020). Christine Ladd-Franklin and the Theory of Colour Vision. SciHi Blog. http://scihi.org/christine-ladd-franklin/

[Review of Colour And Colour Theories, by C. Ladd-Franklin]. (1929). The British Medical Journal, 2(3595), 1013–1013. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25334448