8.9 Community and Crisis at Red River

The HBC continued to trade in all the lands around the bay but increasingly it pushed into the Prairies in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. In 1811 it established a fort and settlement at Red River in response to NWC incursions into what the Royal Charter made clear was territory covered by the HBC monopoly.

The Selkirk Colony

This was done under the leadership of the HBC’s Thomas Douglas, Lord Selkirk (1771-1820), a Scot who had engaged in several other settlement schemes in British North America (all with mixed results). Selkirk was moved by the situation of the Highland and Lowland Scots who were forced off their lands by the clearances — the consolidation of feudal lands to enable the building of greater sheep flocks and thus feed the ravenous woollen industry in industrializing Britain. While touring the Canadas he was feted by the largely Scottish Montreal merchant establishment, which included representatives of the NWC. Knowing something of the strengths and weaknesses of their operations, he returned to Britain where he secured an influential number of shares in the HBC and then convinced the old monopoly to move into the Red River Valley. The Red River or Selkirk Colony (also called Assiniboia) was intended to absorb Highlanders, retired HBC employees, and (eventually) demobilized Swiss mercenaries. The fact that it straddled the NWC’s main access routes and trading territories provoked a decade of hostilities between two already deeply competitive firms.

The Selkirk Colony was enormous, four times the size of New Brunswick and 20% larger than Upper Canada. It contained both NWC and HBC posts. It was, as well, home to large numbers of Métis, some of whom were farmers but most of whom earned at least part of their living from the pemmican trade with the NWC. A high-protein mash of dried bison and berry jerky, pemmican was the staff of life for Western fur traders and was literally the fuel that drove the fast-moving, long-distance NWC canoe brigades. One estimate claims that “several million kilograms of pemmican were consumed in the fur country each year.”[1] The enormous scale of the bison hunts in the 18th and 19th centuries were, in this respect, mobile food-processing operations in which Aboriginal women were a central part. Far from being just a matter of diet, the production, sale, and storage of pemmican was a huge business that operated symbiotically with the fur trade. Neither economy could survive without the other.

The Red River Colony imposed on that economic order and, when famine threatened the settlement in mid-winter 1814, Governor Miles Macdonnell (1767-1828) issued what became known as the Pemmican Proclamation. This law was meant to stop the export of pemmican to NWC forts in the West and retain it for the HBC settlers. If it had been successful it might have ruined the NWC and it certainly would have impoverished the Métis, at least temporarily. Tension between the Métis and the NWC on the one hand and Macdonnell, the HBC, and the Selkirk settlers on the other had been simmering; the Pemmican Proclamation pushed the colony to boiling point. A fearful two-thirds of the settlers prudently left the colony that spring, assisted by an NWC that was only too happy to see them off. The remainder were more or less chased away and the settlement was razed. Selkirk, not to be outdone, found another group of settlers to send to Red River in 1816, along with a new governor, Robert Semple (1777-1816).[2]

Seven Oaks

Matters came to a head on June 19, 1816, at the Battle of Seven Oaks (in present-day West Kildonan in Winnipeg). A party of Métis, having recovered pemmican from HBC posts farther west, were on their way to a rendezvous at an NWC post when they confronted a party from the Red River Settlement, one that included Semple himself. The result was a bloodbath. Semple and 19 others of the HBC people were killed in the shootout; only one of the Métis party died.

Seven Oaks is important in the history of the West and of Canada for at least four reasons. First, it aggravated already very poor relations between the two companies. The fur trade wars were then at full tilt, with HBC and NWC personnel murdering one another across the whole of the West. Second, this chaos was destabilizing and expensive: it stretched both companies to their limit, leading to amalgamation in 1821 under the Hudson’s Bay Company name. Third, it marked the emergence of the Métis as a self-aware nation. The Selkirk Colony gave the Métis an issue on which they could start to imagine a political destiny and it framed an issue of rights to which the Métis would aspire.

Much of the legwork in this process has been ascribed to their leader at Seven Oaks, Cuthbert Grant. The son of a Scottish trader and a woman of Cree or Assiniboine background, Grant was well educated, intelligent, and articulate. According to his biographer, he mobilized Métis feeling in the years leading to Seven Oaks, creating a viable force out of what had been a largely disparate population. The fact that he did so to enable the success of the NWC — with which he and his father had long been associated — takes nothing away from this accomplishment.[3] At Seven Oaks Grant led them to their first “wartime” victory and, as is often said, got “blood on the flag.” The Métis, consequently, would grow as a force on the Plains in the 19th century.

Fourth and finally, Seven Oaks was an important military, commercial, and cultural event. It also resonates as an environmental turning point, as the next two sections argue.

Key Points

- In the early 19th century the HBC moved inland from its seaboard forts and confronted its principal competition.

- The Red River Colony was located at an intersection of conflicting interests in the fur trade.

- The Métis at Red River had a distinctive economic and political role to play.

Attributions

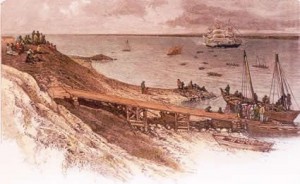

Figure 8.18

Historic dock, engraving by Schell & Hogan from Picteresque Canada, vol.1, pg. 317 (Toronto, 1882). This reproduction is a copy of the version available at parkscanada.gc.ca and cannot be used for commercial purposes.

Figure 8.19

Cuthbert Grant by Jonasz is in the public domain.

- Daniel Francis, "Traders and Indians," in The Prairie West: Historical Readings, eds. R. Douglas Francis and Howard Palmer (Edmonton: University of Alberta Press, 1992), 71. ↵

- Gerald Friesen, The Canadian Prairies: A History, (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1987), 22-90. ↵

- George Woodcock, “GRANT, CUTHBERT (d. 1854),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 8 (University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003). Accessed August 29, 2014, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/grant_cuthbert_1854_8E.html . ↵