7.5 Interwar Years: The Atlantic Colonies

Greater Nova Scotia

The population of Nova Scotia changed radically at the end of the Revolution. In 1764 there were about 13,000 people in the whole colony, which included what would become New Brunswick and Cape Breton. Halifax was easily the largest town but with only 3,000 people. Up to 30,000 Loyalists arrived from the old British colonies and the pattern of settlement changed overnight.[1]

The Saint John River Valley became a particular focus of growth, as did port communities like Shelburne and the Afro-Nova Scotian community of Birchtown — the largest free Black community in North America. Saint John emerged as a modest-sized town and was the first incorporated city in what is now Canada. It was also a highly exclusive centre, with civic laws prohibiting the settling of African-New Brunswickers and barring from the trades and other occupations Whites who were neither Loyalists nor descended from Loyalists. Indeed, Loyalism was more of a fetish in Saint John than in many other settlements. The town attracted many of the most socially distinguished refugees, including the family of General Benedict Arnold (1741-1801), the Continental Army commander who switched to the British side in the course of the war.

The Saint John settlers petitioned London for a separate colony of their own, partly because they felt distant from and ignored by Halifax, but also because they regarded Haligonians as suspiciously democratic in their politics. Thus, in 1784, Nova Scotia was partitioned into two colonies along the Fundy-Chignecto axis. A new capital for New Brunswick was established at Fredericton, nearly 100 kilometres up the Saint John River. This position was more easily defended than Saint John, should the Americans choose to attack some day, but it divided New Brunswick society into an administrative capital and a commercial capital. Acadians returned in growing numbers but they gave the Saint John region a wide berth, preferring to settle instead on the northeast coast of the renamed colony.

The years after 1783 proved particularly disappointing for the part of the Wabanaki Confederacy living in New Brunswick. During the Revolution they had shelved their hostility toward the British and provided support against the American rebels and expansionists from Maine. After the war and the Treaty of Paris, the Mi’kmaq and Malicite were neglected by authorities in both Saint John and Halifax. The Proclamation Act of 1763, which obliged Parliament to address Aboriginal land title, was held to apply only to the Ohio Valley and not to the Wabanaki homeland. The new regimes in Fredericton and Halifax were no less anti-Catholic than was the case before 1775, perhaps more so. This didn’t help the Mi’kmaq, whose people had been converting to Catholicism since 1610. Marginalized in the post-Revolutionary War years, the Mi’kmaq made common cause with other groups who found themselves out of the mainstream: African Loyalists, Irish immigrants, and Acadian returnees. Intermarriage between the groups was common, especially on the south shore of Nova Scotia.

Similar practices occurred in Cape Breton, also carved off from Nova Scotia in 1784. Returning Acadians were generally pushed along through Nova Scotia and on to the island where they settled in communities alongside Irish immigrants. Scots began arriving about the same time. Cape Breton’s future as a community of Gaelic-speaking, coal-mining fiddle players was, however, still some decades away.

The economy of Cape Breton — and that of the rest of the Maritimes — enjoyed a brief surge in the post-revolutionary years. The British Navigation Acts prohibited the transport of British goods on ships that were not British-made. This meant that products of British colonies as well as in the home country could only be carried in ships built either in Britain or her colonies. When the British made it clear that the Acts were going to be applied to post-revolutionary New England (the source of much of Britain’s colonial shipping capacity, lumber, and surplus fish sales), the Maritimes stepped — or fell — into the breach. Shipbuilding, mast-making, and the fisheries expanded to take advantage of the exclusive markets in the West Indies. Sadly, the region simply could not achieve the level of surpluses needed to serve and control the market. Food production in the colonies was limited and little was left over for export. Although shipping surged forward, it could not hope to fill the gap left by New England.

Exercise: Documents

Loyalist Women in Exile

In 1787 Polly Dibblee wrote to her brother, William Jarvis, complaining of the plight of Loyalist exiles in New Brunswick.

Kingston, New Brunswick

[17 November 1787]Dear BillyI have received your two Letters and the Trunk, and I feel the good Effects of the Clothes you sent me and my Children, and I value them to be worth more than I should have valued a thousand Pounds sterling in the year 1774. Alas, my Brother, that Providence should permit so many Evils to fall on me and my Fatherless Children — I know the sensibility of your Heart — therefore will not exaggerate in my story, lest I should contribute towards your Infelicity on my account— Since I wrote you, I have been twice burnt out, and left destitute of Food and Raiment; and in this dreary Country I know not where to find Relief — for Poverty has expelled Friendship and charity from the human Heart, and planted in its stead the Law of self-preservation – which scarcely can preserve alive the rustic Hero in this frozen Climate and barren Wilderness—

You say “that you have received accounts of the great sufferings of the Loyalists for want of Provisions, and I hope that you and your Children have not had the fate to live on Potatoes alone”— I assure you, my dear Billy, that many have been the Days since my arrival in this inhospitable Country, that I should have thought myself and Family truly happy could we have “had Potatoes alone” –but this mighty Boon was denied us!– I could have borne these Burdens of Loyalty with Fortitude had not my poor Children in doleful accents cried, Mama, why don’t you help me and give me Bread?

O gracious God, that I should live to see such times under the Protection of a British Government for whose sake we have Done and suffered every thing but that of Dying—

May you never Experience such heart piercing troubles as I have and still labour under — You may Depend on it that the Sufferings of the poor Loyalists are beyond all possible Description— The old Egyptians who required Brick without giving straw were more Merciful than to turn the Israelites into a thick Wood to gain Subsistence from an uncultivated Wilderness— Nay, the British Government allowed to the first Inhabitants of Halifax, Provisions for seven years, and have denied them to the Loyalists after two years– which proves to me that the British Rulers value Loyal Subjects less than the Refuse of the Gaols of England and America in former Days— Inhumane Treatment I suffered under the Power of American Mobs and Rebels for that Loyalty, which is now thought handsomely compensated for, by neglect and starvation— I dare not let my Friends at Stamford know of my Calamitous Situation lest it should bring down the grey Hairs of my Mother to the Grave; and besides they could not relieve me without distressing themselves should I apply– as they have been ruined by the Rebels during the War— therefore I have no other Ground to hope, but , on your Goodness and Bounty—

I wish every possible happiness may attend you, and your amiable Wife, and Child–and my Children have sense enough to know they have an Uncle Billy, and beg he will always remember them as they deserve.

I have only to add– that by your Brother Dibblee’s Death– my Miseries were rendered Compleat in this World but as God is just and Merciful my prospects in a future World are substantial and pleasing— I will therefore endeavour to live on hopes till I hear again from you— I remain in possession of a graceful Heart,

Dear Billy,

Your affectionate Sister,

Polly Dibblee[2]

Correspondences are a way of showing what one, as the author, thinks but they are also a means of changing the mind of the reader to whom the letter is sent.

What does Polly Dibblee want from her brother? How does she hope that he will understand her situation and that of the Loyalists generally? What message does she wish to convey?

Note that some words are capitalized mid-sentence — is there a pattern?

Prince Edward Island

Prince Edward Island’s situation was unusual in the region. Acadians from all over Nova Scotia fled to the island beginning on 1755, one step ahead of the Expulsion and war. They brought the size of the Acadian population to more than 5,000. Their conditions were difficult: housing was inadequate, food was in short supply following three bad seasons in a row, and everyone was nervous at the prospect of further deportations. They didn’t have long to wait. In 1758 — in the midst of the Seven Years’ War — a local expulsion began. Nearly 1,000 deportees died in shipwrecks on the way to France in late 1758.

In 1767 the whole of St. John’s Island, as it was then known, was divided into 67 lots of roughly 20,000 acres apiece. These were distributed in a lottery in London to aristocratic and other well-to-do investors whose responsibility it was to settle the land with farmers. Rather than wait on a natural flow of immigrants, this experiment proposed to draft settlers into a quasi-feudal tenant-farmer agricultural colony. The project failed badly. Settlers were slow in coming and the absentee landlords (or proprietors) sometimes abandoned entirely their obligations to the colony. From late in the 18th century until the 1870s, the Islanders would petition and demand of Britain that the unsettled and unserviced land be put up for freehold sale. Islanders were convinced that this system was a drag on their economic growth and a constraint on investment in the colony.

Efforts to seize defaulting proprietors’ lands led to the recall of Governor Walter Patterson in 1786. It was out of this failed attempt to repossess the land — a process called escheat — that Islanders initiated an indigenous political movement and the Escheat Party, which was clearly in opposition to the interests of the larger landowners and their British sponsors. In 1798, in order to avoid confusion with St. John’s, Newfoundland, and Saint John, New Brunswick, the British government changed the colony’s name to Prince Edward Island. The colony developed strong links with British markets and was an early tourist resort for wealthy travellers from late 18th century England and for ships sailing out of New England.

Newfoundland

The War of Independence was a pivotal time for Newfoundland. The fisheries economy of the colony was always exposed during wartime because of the demand created for naval sailors, many of whom were plucked from Newfoundland’s cod industry. As well, Newfoundland shipping was increasingly vulnerable to American privateers who could, by seizing Newfoundland craft, hurt the British economy, reduce the size of the Newfoundland fleet, deny the Royal Navy some sailors, and head for home with a valuable supply of cod. The loss of food supplies from New England in the early years of the war was an even more significant trauma for the island colony, one that provoked famine conditions for two years.[3]

The population of Newfoundland was made up mostly of transient fishermen, people who worked with the fleets from Europe without sinking roots into the outport communities and the resident community. The transients left in large numbers as wartime conditions worsened. For the first time, Newfoundlanders were mostly residents.

Increasingly, the residents became merchants. The business model of the transient or migratory fishery had been irrevocably damaged by the war and Britain could no longer run the colony as a fishery station. Now there was room for residents to engage more fully with the fisheries and with import/export economies, as was made clear with two developments.

First, St. John’s emerged as a hub of commercial and administrative activity. At the end of the Revolution there were barely a thousand people in St. John’s; less than 30 years later there were more than 10,000. Second, the population of the colony as a whole expanded dramatically, rising to 20,000 in 1800. Fed mostly by Irish immigration (both Catholic and Protestant), the population continued to grow into the mid-19th century.

Tension existed within this community because Newfoundland lacked a formal, elective type of government; in its place it had a small elite of St. John’s merchants (mostly Protestant) and an officers’ corps, both of which advised the governor. This arrangement alienated some of the Irish and others in the community, and led to a failed coup in 1800, which ended with the execution of eight members of the conspiracy.

More subtly, the demographics of Newfoundland did much to shape the community that evolved. At the start of the century one legacy of the transient fisheries was still evident: the distorted ratio of men to women. Because Britain did not (officially) want to stimulate settlement and colonial population growth, it had discouraged female immigration. As residency grew, this constraint was lifted and the number of women in Newfoundland increased, resulting in an intensification of permanent settlement in individual outports.

Regular traffic between Newfoundland and Ireland enabled men to find brides at home and bring them to the colony. It also produced generations of children, something that had not been witnessed in the Euro-Newfoundlander population in any significant numbers before 1800. For the first time, education became the focus of attention. As Willeen Keough has shown, the arrival of Irish women on the southern Avalon created a cadre of females who were part- or full-owners of fishing businesses (called “plantations”), employers of fisheries “servants,” active in the shore crews, owner/operators of small businesses, farmers, and key to the emergence of a household economy consisting of more than one generation.[4]

These changes in Newfoundland society had a visible impact on the landscape. Forests along the foreshore were cut down and used for lumber and fuel. Even before the great boom in Newfoundland’s forest industry in the 19th century, more and more rock was emerging from underneath the stumps of former tree stands. Whaling, which had been a pastime of the Basque fleet for centuries, had severely reduced cetacean numbers and may have stimulated the health of the cod population as they were no longer prey or competitors of the large sea mammals. The capture of foreshore positions for fishing stations and deforestation had another impact: it reduced Aboriginal access to traditional resources.

The Beothuk, an Algonkian-speaking group about whom little is known, engaged in trade and scavenging but increasingly avoided direct contact with Europeans as the fleet-sizes increased.[5] They retreated inland when the European fishing crews were on shore, and then raided their abandoned sites for metal nails from which they could fashion their own tools. There was armed conflict between the Beothuk and the Europeans, and also against the Mi’kmaq who had settlements along the south coast of Newfoundland. The Beothuk depended heavily on the migratory caribou herd, which was impacted by European settlement on the Avalon Peninsula, and on the spawning routes of the salmon fishery, which was disrupted by Euro-Newfoundlanders’ logging along the island’s river systems.[6]

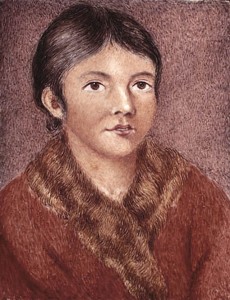

Exotic diseases cut a swathe through their population, especially tuberculosis. By the start of the 19th century, the resource base of the Beothuk was badly depleted and they were facing famine. In 1819 and 1823, two women from a shrinking Beothuk population established the longest known relationships with Europeans. The first, Demasduit, was captured in a brutal assault that claimed the life of her husband and doomed her infant child. She nevertheless lived in St. John’s for nearly a year before perishing from tuberculosis. Shanawdithit and two members of her family were on the brink of starvation when they threw themselves on the mercy of the European community. Her relations died soon after — again, from tuberculosis — and Shanawdithit succumbed herself after six years among the Europeans. Much of what is known about the Beothuk derives from these two brief encounters. By 1829, or possibly not long after, the Beothuk were extinct.

The Beothuk were among the first Aboriginal people to encounter Europeans. Their disappearance in the early 19th century had a number of impacts on colonial understanding of indigenous peoples. The Beothuk were characterized for generations as a primitive people, a Paleo-Indian branch that was backward by Aboriginal standards and thus doomed to disappear. Explaining their extinction implicitly involved exculpation of European guilt: if they were doomed, they were doomed and nothing that Europeans did to slow or hasten that outcome would matter. What’s more, the Beothuk — the original “red indians” — as a “fated” people were invoked as foreshadowing of what awaited Aboriginal people across North America.[7]

Key Points

- The Loyalist migration transformed and complicated the population and political geography of Nova Scotia and Quebec, producing new colonial configurations and social problems.

- The colonial landscape of Prince Edward Island was swept clean and was marked by a unique absentee landowner class.

- Newfoundland’s settler society was spurred on by the commercial possibilities created by the Revolution and it started to grow in earnest.

- The fate of the Beothuk points to the ecological incompatibility of the newcomer and Aboriginal societies on Newfoundland.

Attributions

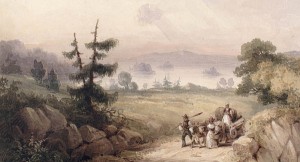

Figure 7.10

Bedford Basin near Halifax by Robert Petley is in the public domain. This image is available from the Library and Archives Canada, acc. no. 1938-220-1.

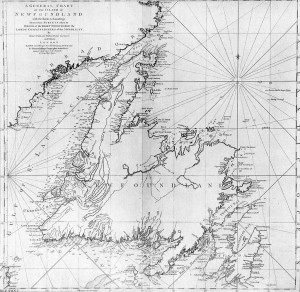

Figure 7.11

Prince Edward Island map 1775 by SriMesh is in the public domain.

Figure 7.12

Cooks Karte von Neufundland by Schaengel89 is in the public domain.

Figure 7.13

Demasduit by Nikater is in the public domain.

- Statistics Canada, Censuses of Canada, 1665-1871. http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/98-187-x/4064810-eng.htm#part3 ↵

- Letter from Polly Dibblee to William Jarvis, 17 November 1787, Kingston, "Loyalist Women in New Brunswick, 1783-1827," Atlantic Canada Virtual Archives, diplomatic rendition, document no. 13_41. Audit Office, series 13, bundle 41, is available at National Archives, London. ↵

- "Exploration and Settlement," Newfoundland and Labrador Heritage. http://www.heritage.nf.ca/exploration/amer_rev.html. ↵

- Willeen Keough, "The Riddle of Peggy Mountain: Regulation of Irish Women's Sexualtiy on the Southern Avalon," Acadiensis 31, no. 2 (Spring 2002): 38-70. ↵

- William Gilbert, “Beothuk-European Contact in the 16th Century: A Re-evaluation of the Documentary Evidence,” Acadiensis XXXX, no. 1 (Winter/Spring 2011): 24-44. ↵

- Ralph T. Pastore, “The Collapse of the Beothuk World,” Acadiensis XIX, no. 1 (Fall 1989): 59-64. ↵

- Donald H. Holly Jr. and Paul Sant Cassia, "A Historiography of an Ahistoricity: On the Beothuk Indians," History & Anthropology 14, issue 2 (June 2003): 127-40. ↵