6.6 Contrasting Farming Frontiers

The colonies north of Virginia were built on a model of small independent producers: farmers who owned and worked their own piece of land usually using family labour. This model was very different from the historical system of British farming under feudalism, which was based on peasants being under obligation to landlords. Although most coastal colonies (Newfoundland, Maine, Boston, New York) were oriented to fishing, the bulk of colonial growth from New England south to the Potomac River was based on the land ownership model of independent farmers. These colonies were not free of slavery, but it was never applied as extensively or as intensively as in the plantation colonies to the south, where the land parcels were much larger.

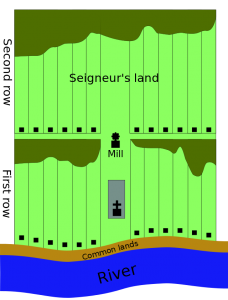

All the English colonies generally adhered to a block-shaped survey pattern of farmland, which was different from the seigneurial system in New France. There, farms were divided into long strips of land running back from the river and administered in a quasi-feudal relationship with the seigneur, who was obliged to provide the community of habitants or censitaires a mill, a church, and other built facilities in support of their farming efforts.

The different land use patterns had different implications. A colony that covered the landscape like a spreading checkerboard (the English system) was more difficult to subdue by an army, but impossible to defend against guerrilla-style offensives. Massachusetts developed in this township pattern: Boston remained pre-eminent as the colony’s port and centre of commerce, and there were several smaller tidewater settlements, but the second tier of rural towns were all more or less equal, and they carpeted the colonial landscape rather than running across it in a string. Family homes in the English colonies, however, were more likely to be clustered in a village setting around a square or commons, which strengthened community ties, but also made small, individual towns a good target for raiding parties from the north.

In contrast, the French model of narrow strips of property along the river was more easily patrolled (and taxed), but also vulnerable to an invading naval force sailing up the St. Lawrence, which could — and did — systematically lay waste to one farm after the next. The river and, from the 1730s, the Chemin du Roy at the back of the first row or rang of seigneuries connected the major settlements with the markets. It also allowed neighbouring farm families to see each other’s homes and promote a lively Canadien culture. As well, it made possible the unchallenged rise of three main settlements: Montreal, Trois Rivières, and Quebec.

Exercise: History Around You

Seigneurialism’s Fingerprint

Landscapes are historic documents. Take a look at the map coordinates below using satellite images such as Google Earth.

- 45°09’49.2″N 123°01’59.9″W

- 53°33’57.1″N 113°26’20.6″W

- 49°44’10.4″N 97°07’14.2″W

- 29°56’40.7″N 90°09’13.7″W

- 49°54’56.2″N 97°07’09.8″W

- 42°23’03.8″N 82°54’45.4″W

These images show evidence of French and/or Métis occupation. If you look closely, can you see where the seigneurial strips run up against other kinds of land use? What is the consequence in urban areas?

Land and Society

Land use also impacted the family structure in the French and English colonies. Inheritance laws in New England placed a premium on primogeniture, the practice of leaving the majority share of the property to the eldest male heir. In Canada, coparcenary ensured that widows inherited half of the estate and all of the surviving children got their own share — all of which were divided in a pattern of long and progressively narrower and narrower strips. Those who had to move away might, however, find land nearby in the deuxième or troisième rang, the subsequent range or row of farms in the same seigneury. In practice, these narrow strips of land were uneconomical to farm and so they were farmed together (or one sibling might buy out another), the end effect being that more members of an extended family remained on the land. In contrast, in New England, the “secondary” offspring and the widow of the landowner often had to look elsewhere for their fortune, sometimes moving to another piece of land farther west and generally nearer to the frontier of colonial settlement.

On balance, free land without any feudal encumbrances had a greater attraction to potential settlers than did the quasi-feudal qualities of the seigneurial system. Setting aside the climate differences between New England and Canada, this accessibility to land and the lack of Old World systems of deference seems to have worked to the advantage of the English colonies, which grew much more rapidly. Economic historians have long debated whether the seigneurial system was a drag on the Canadian economy as censitaires transferred some of their income in the form of rents to seigneurs who, in turn, sent much of that wealth out of the colony.[1] On the whole, it seems likely that this quasi-feudal relationship came at a high cost; it is difficult to determine whether the additional infrastructure costs associated with the English landholding system (the expense of building roads and of the individual farmers having to provide their own mills) had comparable negative impacts.

Farms in Acadia, as we have seen, were different again. There, drained marshland was the focus of farming efforts and individual ownership was the rule. Large families were the norm in the 18th century and yet subdividing of property did not reach a critical point before the expulsion took place. As was the case in Canada and Virginia, most Acadian properties were on waterways and towns or villages of any size were few, far between, and small.

Key Points

- Agricultural colonies differed in their land-ownership systems.

- Land-use differences created and/or reinforced distinct administrative and social relations.

- Town and city growth was limited in some colonies because of their economies and economic geography.

Attributions

Figure 6.2

Seigneurial system by Cleduc is used under a CC-BY-SA 3.0 license.

- R.C. Harris, The Seigneurial System in Early Canada: A Geographical Study (Montréal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1966); Allan Greer, Peasant, Lord and Merchant (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1985); Leslie Choquette, Frenchmen into Peasants: Modernity and Tradition in the Peopling of French Canada (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997). ↵