6.10 Acadia 1713-1755

Historians think of Acadia as a society as much as a place. After 1713, the French possessions in the region were both reduced and augmented. Île Saint-Jean and Île Royale were some distance from the Bay of Fundy where most of the Acadian settlements were located. Those were now under the nominal control of the British. The two islands held a rump population of Acadians but, soon after Utrecht, the French erected the largest of their colonial outposts on Royale: Fortress Louisbourg. Built in 1720, Louisbourg soon became the busiest of the French ports in North America and rivalled most of the British ports to the south in terms of volume of trade. Clearly it had both military and commercial functions. It also served as the administrative headquarters for the two colonies in the Gulf of St. Lawrence.

Louisbourg played a role, too, in sustaining the Acadian communities then behind enemy lines in Nova Scotia. At first the French sought to entice Acadians from the Bay of Fundy to resettle on Île Royale. The soil around Louisbourg, however, was too miserly so the Acadians opted to stay put. This pleased the British insofar as Acadian farms contributed positively to Nova Scotia’s bottom line, but the question of Acadian loyalty was to dog both sides for decades. The British were certain that Louisbourg was a disruptive factor in the internal affairs of Nova Scotia; the Acadians were exasperated by years of war and oscillations between British and French overlords, on the one hand, and enemy pirates and raiders on the other. The French, for their part, wanted some time to rebuild their position without being drawn too far into the affairs of the Acadians and the Wabanaki Confederacy.

Repeated efforts were made on the part of the British to secure an oath of loyalty from the Acadians. France, of course, did not want this but, more importantly, neither did the Wabanaki Confederacy. Pro-British Acadians, the Wabanaki concluded, would be by definition hostile to the Confederacy. Indeed, the French spurred on Wabanaki attacks on the British throughout the 18th century, using the Confederacy as the means to harass their enemy.

The Third Wabanaki War

The Wabanaki did not need much encouragement. Immediately after Utrecht they complained of British and New Englander incursions into their territory and pointed out that, regardless of what France signed away, they did not agree to any division of their lands with the Europeans. This was definitely true of the Mi’kmaq and probably the Abenaki (Malecite) as well. The New Englanders understood the situation differently and repeatedly edged into Wabanaki territory, establishing settlements and sometimes forts. This occurred over a broad geography, from Vermont to Île Royale, and the Wabanaki response was, likewise, wide-ranging. The Third Wabanaki War (also known as Father Rale’s War) entailed serious frontier squirmishes, naval battles, assaults on fortified positions, and guerrilla attacks designed to terrorize one another. From 1722 to 1725 the Confederacy launched raid after raid on British settlements in New Hampshire, Vermont, Maine, and Nova Scotia. They targeted individual towns and farmhouses in an attempt to drive the New Englanders back to their pre-1713 positions and the British from their newly claimed lands. The New Englanders retaliated and the British established Fort Canso, a fishing post and defensive position across Chedabucto Bay from Île Royale, in a territory that was unambiguously claimed by the Mi’kmaq.

For the most part these hostilities — although almost continuously running and bitterly fought — were inconclusive. However, in the western theatre of war the Confederacy and New England came to an agreement called Dummer’s Treaty (1727), named for the Governor of Massachusetts. The terms were not favourable for the Confederacy but they established the principle that the Wabanaki were legitimate inhabitants of the region now described as New Brunswick and that they would have to be consulted in future diplomatic agreements.

Acadia’s “Golden Age”

Despite the conflict in Maine and eastern Nova Scotia, life in the Bay of Fundy was largely peaceful for the core Acadian settlements. Their system of governance was like that of the English colonies although with a slight seigneurial twist. A century of benign neglect by France had come with a cost in terms of security and vulnerability but there were freedoms arising from that as well. Local councils provided a largely informal administrative system, one that (after Utrecht) sent representation to the British headquarters at Annapolis. The British showed official tolerance for Catholicism, although the colony was not especially well supplied with clergy. What churchmen there were provided a level of leadership but not authority, another distinction from what existed in nearby Canada under the royal administration.

The period from 1713 to 1748 has been described by historian Naomi Griffiths as a “golden age,” one in which family sizes grew and average life expectancies improved and were better than in France, Canada, or New England. Direct involvement in war was very limited, epidemics ignored the growing Acadian settlements, and commerce with New England was conducted in a largely effective and mutually beneficial way. Illicit trade with Louisbourg also thrived as Acadians shipped boatloads of surplus livestock to the French bastion.[1]

Some of these quality-of-life indicators can be measured and verified but, against that trend, this was also an era of significant Acadian and Mi’kmaq migration out of the Fundy Basin and onto Île Saint-Jean by the 1750s. As well, the putative peacefulness of the region was regularly jeopardized by British imperial designs and Mi’kmaq resistance. The existence throughout this period of an Acadian militia also indicated that things were not all well among the people known to the British as “the neutral French.”

The story of Acadia from 1713 to the 1750s sometimes references the benefits of isolationism. By staying out of the way of wars, minimizing contact with their neighbours, and growing rapidly from internal sources, the Acadians were able to avoid combat deaths, epidemics, and internal division. This is not supported by evidence of extensive external trade and considerable immigration: a third of the individuals involved in 174 marriages at Grand-Pré in the 18th century came from France, Île Royale, and even Canada. Whatever caveats might be added to the story of a “golden age,” Griffiths is right that the key to understanding the more positive aspects of this community memory is that it sustained the Acadians in what was to come after 1748.

Nova Scotia, Acadia, Wabanaki

European war from 1740-48 (the War of the Austrian Succession) provided the French with an excuse to attack Nova Scotia from Louisbourg. In reply, New Englanders mounted an assault on the fortress and found its defences to be easily penetrated. Louisbourg was captured in June 1745 and, for the next three years, the British and New Englanders controlled the whole of the North American foreshore from Georgia to Newfoundland. They took advantage of this situation to clear Île Royale of several thousand francophones, including many Acadians. This was a grim foretaste of things to come.

The New Englanders’ capture of Fortress Louisbourg was not a victory they were able to enjoy very long. The 1748 Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle (which restored the status quo ante bellum) had several immediate consequences for the Acadians and the Mi’kmaq. The first of these was pressure from the French to take their side, an offer the Acadians declined. Knowledge that their Acadian subjects might yet jump to the enemy, however, placed the British in a dilemma. The prospect of an end to Acadian neutrality and the certainty of renewed Mi’kmaq hostilities prompted the British to establish new positions in Mi’kmaq territory. The foremost of these was Halifax, placed squarely where the British had earlier promised the Mi’kmaq they would not go: at Jipugtug (Chebucto). Its establishment in 1749 and the arrival of more than 2,000 settlers resulted in another conflict that came to be known as the Mi’kmaq War or Father Le Loutre’s War.

Halifax was established under the governorship of Edward Cornwallis (1713-1776), a 36-year-old British aristocrat who started his term hopeful that peace could be established with the Wabanaki Confederacy. Initially it looked as though his goals would be realized: he had a good-sized core of British settlers, Royal Navy support, and a signed agreement with the Wabanaki. Sadly, the Mi’kmaq were not part of the treaty process. They responded with a letter that made clear their position: “The place where you are, where you are building dwellings, where you are now building a fort, where you want, as it were, to enthrone yourself, this land of which you want to make yourself absolute master, this land belongs to me.”[2] Mi’kmaq attacks followed soon after.

Cornwallis’s response was to stand his ground and, indeed, to expand the British military presence in the region. New forts and barracks went up at Windsor, Dartmouth, Grand Pré, Bedford, Mirligueche (Lunenburg), and Chignecto (Fort Lawrence). Much of this construction was in and around the Minas Basin, part of the Acadian heartland. The disputed territory to the north (the area that later became New Brunswick) bristled with French forts in response. Cornwallis’s gestures may have been large but his effectiveness was questionable. In 1749 he announced a bounty on Mi’kmaq scalps. This was a practice common in New England for a century or more and the French were already offering the Mi’kmaq a bounty on British scalps. The bounty was wholly ineffective and failed to mobilize a strong response to the Aboriginal militias.

Father Jean-Louis Le Loutre was a Catholic priest deeply involved in the Wabanaki resistance and, when it came to English scalps, the paymaster of the French as well. In the late 1740s he organized an Acadian exodus to Île Saint-Jean. Reducing the number of Acadians in Nova Scotia was a means of weakening British food supplies, but the French/Acadians/Wabanaki were able to keep open and protect a land corridor that ran across the disputed territories, the Chignecto Isthmus, making travel from Canada to Louisbourg possible.

Under the circumstances, Cornwallis could not gain any ground, nor could he subdue his opponents. He left the colony and the war dragged on inconclusively until 1755. The legacy of his term, however, is important: no comparably sized region in the history of British North America was ever so militarized, no conflict so intractable, and never was so much potential goodwill lost. What looks on the face of it like an Acadian victory was in fact a disaster, one that unfolded in different ways. The Acadians who relocated to Île Saint-Jean were beset in 1749 by a plague of black mice that destroyed their crops. This was followed by another plague in 1750, this time of locusts. In 1751 drought struck. And, of course, the British were becoming increasingly exasperated with the Acadians. Hundreds if not thousands had abandoned neutrality and sworn loyalty to France. Indeed, many of the British settlers brought in by Cornwallis and his successor — some of whom were actually German and French Protestants — deserted the British and joined the Acadians and the French.

Oaths and Exile

The new governor of Nova Scotia, Charles Lawrence (1709-1760), decided to push the issue of an Acadian oath of loyalty. The Acadians who remained in the Minas Basin and generally on the north shore of Nova Scotia were still reluctant. International circumstances had changed, however. War had broken out in the Ohio Valley in 1754 and Europe was edging toward another precipice of its own. A joint British-New England operation captured Fort Beauséjour. The Wabanaki raids, too, continued. Further Acadian refusal to take the oath in 1755 prompted Lawrence, with the support of Governor William Shirley of Massachusetts, to begin relocating Acadians to the British colonies to the south, to France, to Louisiana (where they adapted to bayou life as Cajuns), to wherever they could be sent.[3] The British forces set ablaze the emptied Acadian villages and then repopulated them with British American colonists called planters and by new immigrants from Yorkshire. The Acadian Expulsion (in French, Le Grand Dérangement) did not occur overnight. This was an eight-year long episode, during which time some Acadians returned, a great many perished, one group hijacked their captors’ ship and sailed to Canada, and those on Île Saint-Jean thought, mice and locusts notwithstanding, they had made a smart move.

Key Points

- The Treaty of Utrecht (1713) redefined the boundaries of Acadia in such a way as to worsen tensions between the French, the British, the Wabanaki Confederacy, and the Acadians.

- The Acadian response to repeated turnovers in imperial masters and ongoing tensions was to seek a position as the “neutral French.”

- Acadian communities enjoyed significant growth in this period, marked by natural population growth and increased farm productivity.

- Renewed struggles between the French and the British and between the British and the Mi’kmaq at mid-century resulted in a more militarized region and, ultimately, the Acadian Expulsion.

Attributions

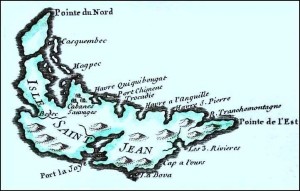

Figure 6.9

Acadie1744 IPE by Jeangagnon is in the public domain.

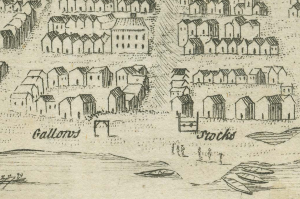

Figure 6.10

Plan de Louisbourg vers 1751 by AYE R is in the public domain.

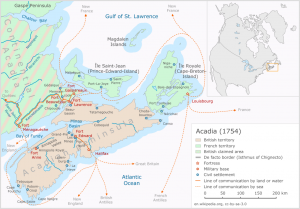

Figure 6.11

StocksHalifaxNovaScotia1750 by WarBaCoN is in the public domain.

Figure 6.12<

Acadie 1743 nl by Mikmaq is used under a CC-BY-SA 3.0 license.

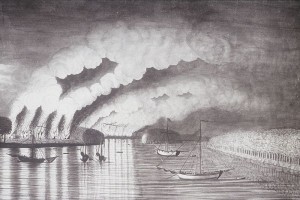

Figure 6.13

A View of the Plundering and Burning of the City of Grymross by Hantsheroes is in the public domain.

- Naomi Griffiths, "The Golden Age: Acadian Life, 1713-1748," Histoire Sociale/Social History 17, 33 (May 1984): 21-34. ↵

- Quoted and translated in L.F.S. Upton, Micmacs and Colonists: Indian-White Relations in the Maritimes, 1713-1867 (Vancouver: UBC Press, 1977), 201. ↵

- The complex context of the expulsion is considered in Naomi Griffiths, From Migrant to Acadian: A North American Border People, 1604-1755 (Montréal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2005), 431-64. ↵