4.8 Louisiana and the Pays d’en Haut

The Wendat Confederacy collapsed in 1649 following tragic defeats by both smallpox and the Haudenosaunee. The loss of their favoured middlemen in the fur trade, however, enabled French voyageurs to push beyond the boundaries of Wendake (Huronia) and into the upper Great Lakes. In 1659, Pierre-Esprit Radisson and Médard Chouart des Groseilliers, who would go on to lead the British charge into Hudson Bay, were the first French traders to reach the western shore of Lake Superior. The 1670s and 1680s saw missionary and exploratory activity expand in the region — known as the Pays d’en Haut. Still searching for a route to the Pacific, voyageurs were initially hopeful about the Mississippi system. They soon realized that they were to be disappointed. Nevertheless, in 1699 French territorial claims in North America expanded dramatically when Louisiana was founded in the basin of the Mississippi. Until 1713, the French laid claim to a trading network that extended from Plaisance through Acadia and Canada, as far north as Hudson Bay, all around the Great Lakes and down to the Gulf of Mexico. This network was maintained through a vast system of fortifications.

Louisiana and the Ohio

Louisiana was the southernmost administrative district of New France and was under French control from 1682 to 1763 and 1800 to 1803. It originally covered a far-reaching territory that included most of the drainage basin of the Mississippi River and stretched from the Great Lakes to the Gulf of Mexico and from the Appalachian Mountains to the Rocky Mountains. The relative success of the New France project rested in the ability of the French to hem in their competition and, in this respect, Lousiana and the Ohio were as integral to the success of Canada, as Canada was to that of the Pays d’en Haut and the Mississippi. By means of careful diplomacy among the Aboriginal nations of the Ohio Valley and the lands on either side of the Mississippi, the French were able to contain the British settlements to the east of the Appalachian Mountains until the mid-18th century. As well, they were able to exploit Aboriginal dissatisfaction with British colonists even within the English colonies. This was the case in South Carolina in the early 1700s when Aboriginal frustration with English trade partners and colonists made Louisiana an attractive alternative source of goods. In this way the French were able to work through third parties to hinder the survival of their English foes. The French pursued a virtually identical strategy in the south where they competed effectively against the Spanish. French rifles and other goods spread out across east Texas and as far west as New Mexico, undermining what loyalty and/or deference the Spanish were able to command among their own Aboriginal allies.

The bridges between Louisiana and Canada were the Ohio and Illinois Valleys. Inaccessible to the French until the 1700s, the territory had changed hands between Aboriginal groups during the period called the “Beaver Wars.” For reasons that go well beyond an interest in gaining dominance in the beaver-pelt trade, the Five Nations League expanded westward, raiding for personnel and subduing potentially dangerous neighbours. In the process, they drove off much of the indigenous population of the Ohio Valley, unintentionally making it more attractive to two groups: Aboriginal peoples being squeezed out of the region east of Appalachia (across which British-American settlement was spilling) and Euro-North Americans who saw opportunities and dangers in a vacuum. French efforts were the most substantial once peace had been won with the Haudenosaunee.

By means of gift diplomacy the French hoped to guarantee Aboriginal support in the region and use it to keep the British out of the Ohio. From the Ottawa Valley south to Louisiana, New France had a small population. It relied heavily on friendly contacts with local Aboriginal communities. Because the French settlers lacked the appetite for land that characterized English settlement, and because they relied exclusively on Aboriginal peoples to supply them with fur at trading posts, the French built a complex series of military, commercial, personal, and diplomatic connections. These became the most enduring alliances between the French and the Aboriginal American community.

In 1682, the French explorer de La Salle named the region Louisiana to honour France’s King Louis XIV. The first permanent settlement, Fort Maurepas, was founded in 1699 near the mouth of the Mississippi by Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville, a French military officer from Canada. An inland trading post followed in 1714 in the territories of the Natchitoches, which served as an interface between French, Aboriginal, and Spanish/Mexican commercial interests in Texas. Soon cotton plantations began to appear.

The South and West in New France

For historians of Canada, Louisiana is an opportunity to test certain assumptions. Individuals like d’Iberville connect the histories of the two regions, so they were not entirely isolates. News of practices in one could reach the other, while at the same time, distinctive and seemingly contradictory trends could be found. The seigneurial system never took root in Louisiana (nor was it applied to Île Royale or with any rigour to Acadia); instead, individual land title was made available. Social relations were different as well. Colbert introduced the Code Noir in 1685 to regulate slavery and establish racialized boundaries in the French sugar colonies; its tenets were subsequently transferred to Louisiana to support slavery in the cotton plantation economy after about 1717. Slavery was, to be sure, found in Canada although it was more likely to involve Aboriginal slaves than Africans and more likely to be domestic in character than forced agricultural labour. But what is perhaps more noteworthy is that while interracial marriage and miscegnation occurred everywhere else in New France, in Louisiana’s plantation districts it was officially prohibited. Spread thinly everywhere but the St. Lawrence, Acadia, and New Orleans, the French coureur de bois readily married into local Aboriginal communities. This was, of course, a diplomatic strategy as well as a biological/sentimental one: working in such small numbers, the French outside of the main population centres had to make an effort to be on good terms with their hosts. To turn this comparison on its head, why was slavery not the norm in Canada? The Canadien economy was simply not one that could benefit from or sustain an army of forced labour.

In some respects there were peculiar similarities between the colonies. Where Canada and its hinterland had a trade in beaver pelts and moose hides, Louisiana’s chief export for many years was deer skins. The Choctaw nation was the main supplier, and they were as closely aligned with Louisiana as the Wendat had been with Canada. Another parallel was the rivalry between the Choctaw and the Chickasaw, the latter being allies and trading partners of the English in South Carolina. Both Aboriginal groups found themselves trading their captive enemies to their respective European allies as slaves.[1] As the French discovered, to their chagrin, accepting a slave-gift from one allied nation meant that the slave’s nation of origin was ruled out as another ally. In this way, Aboriginal slave exchanges purposefully set limits on whom the French could engage with diplomatically.[2] This was particularly the case in the Pays d’en Haut.

Distances between the colonies within New France were so great that each region enjoyed a certain amount of autonomy. Although New France as a whole was governed out of Quebec City and, later, Montreal, Louisiana was administered principally from Mobile, then Biloxi, and finally from New Orleans. Upper Louisiana extended into the Illinois territory and was a zone in which New Orleans’ authority competed with Montreal’s. Throughout much of Louisiana and the Pays d’en Haut, administrative control was more theoretical than practical; French settlers and farmers soon found themselves integrated less into a European system and more into an Aboriginal world.

Key Points

- At its maximum size, New France was much more than Canada and Acadia.

- Louisiana and the Pays d’en Haut were principally areas of French influence, rather than settlement colonies.

- Each of the regions of New France had distinctive economic and social characteristics and a degree of mutual autonomy.

Attributions

Figure 4.15

Vincenzo Coronelli Partie occidentale du Canada 1688 by Jeangagnon is in the public domain.

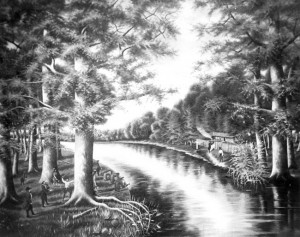

Figure 4.16

ArkansasPost1689 by Samuel Peoples is in the public domain.

Figure 4.17

Nouvelle-France map-en by Pinpin is used under a CC-BY-SA 3.0 license.

Figure 4.18

Ft de Chartres-bastion-1 by Kbh3rd is used under a CC-BY-SA 3.0 license.

Long description

Figure 4.17 long description: In 1713, France held modern day Labrador, much of Quebec, southern Ontario and southern Manitoba and a part of Saskatchewan. Their territory also stretched south through the middle of the eastern United States all the way down to the top of the Gulf of Mexico. Britain held the eastern coast of the United States and had recently acquired Newfoundland, Nova Scotia, and parts of Northern Onatio, Quebec, and Manitoba. Spain held Florida, parts of the central United States, and Mexico. [Return to Figure 4.17]