4.2 Acadia

A half century would pass between Cartier’s kidnappings of Aboriginal men along the St. Lawrence and the arrival of French delegations determined to build a sustained presence. Not surprisingly they would do so first in the lands closest to Europe and near the riches of the Grand Banks fisheries. This territory would become known as Acadia.

Both the Portuguese and the British briefly established positions in the region in the 16th century, but neither built lasting settlements or trading posts. The Portuguese enjoyed a singular advantage in this field: the Azores, a chain of small islands roughly halfway between the European mainland and Newfoundland. This stopping point between Europe and the Grand Banks enabled Portuguese and Basque fleets to make the voyage into the western Atlantic with relative security and was a key factor behind long-term Iberian involvement on the fisheries and whaling grounds. Their endless supplies of salt, moreover, made it possible for the Iberians to preserve their catch of cod without bothering to make landfall. Had they wanted to, they could easily have dominated Newfoundland and its waters. Doing so was, simply, unnecessary.

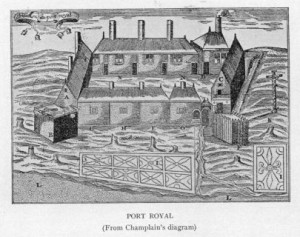

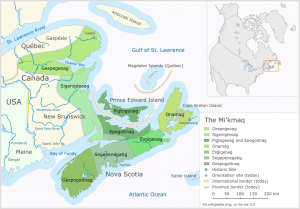

French missions followed in the late 16th century and were both tentative and unsuccessful at first. There were abortive efforts — on Sable Island using convict settlers in 1599, at Tadoussac the year after, and on Ste. Croix in 1604 — but a viable presence was only established in July 1605, when Port-Royal was founded on the Bay of Fundy in what is now Nova Scotia. Port-Royal was to become the hub of a French colonial territory in what 16th century European maps described as “Arcadia.” The French dropped the “r” and Acadia eventually stretched from Castine (in what is now the mid-coast of Maine), across Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island (Île Saint-Jean), and all the way to the south coast of Newfoundland.

As colonies go, what distinguishes Acadia as an administrative unit is that so much of it was water: the Gulf of St. Lawrence, the Bay of Fundy, the Gulf of Maine, Cabot Strait, and a long stretch of the Atlantic Ocean. The Gulf of St. Lawrence is roughly circular and many of the key settlements were along its edge. There were exceptions, and they were very important.

One of the principles embraced in this book is using the group names that peoples preferred for themselves. The people of Acadia are, thus, Acadiens. We could go the extra step and refer to Acadia as “L’Acadie” but, in the interest of keeping it simple, we won’t. The English-language version of the group name – “Acadian” – appears here when used in the context of British administration of or campaigns against the Acadiens. Thus, the “Acadian Expulsion” (which in French is Le Grand Dérangement). Many of the deported Acadiens wound up in Louisiana where their group name evolved into Cajuns, a small jump from les Acadiens but a much bigger leap from “Acadians.” The Acadien people in the Maritimes have survived the disruptions of imperial and inter-colonial wars and they remain one of the strongest threads in the fabric of regional cultures. It is, indeed, the oldest continuous colonial culture in what is now Canada and the two branches of the Acadien family constitute one of the oldest European-descended cultures in North America.

A Difficult Start

The first French settlers arrived mainly from the west-central region of France called Vienne, near Poitiers. (The later settlers of the St. Lawrence originated farther to the northwest, from around Normandy and Paris.) The colony’s first hundred years were marked by conflict and troubles. Port-Royal was barely eight years old in 1613 when a British force out of Virginia burnt it to the ground.

A civil war that lasted until 1645 broke out in 1640 between Acadiens based in the Port-Royal area (and loyal to Governor Charles de Menou d’Aulnay de Charnisay, a Catholic governor) and those attached to the settlement at the mouth of the Saint John River (and affiliated with the Protestant governor, Charles de Saint-Étienne de la Tour). France had badly misunderstood the geography of Acadia and had provided two highly competitive governors for an area divided by only 23 kilometres of water. After many naval and land battles, d’Aulnay came out slightly ahead. In the siege of Saint John (launched by d’Aulnay in April 1645 when La Tour was away in New England), the “Lioness of La Tour,” Françoise-Marie Jacquelin — Charles de la Tour’s wife — led the defending troops. The fort fell and despite promises of mercy, d’Aulnay hanged the garrison; Madame La Tour died in captivity shortly thereafter.

The Acadien civil war, as bloody and pointless as it was, underlines the many curious aspects of life in the 17th century colony. First, it wasn’t entirely the imposition of one people over another. The Wabanaki Confederacy of Penobscot, Mi’kmaq, Maliseet, and Abenaki peoples grafted the Acadiens onto their lives and struggles. Faced with aggressive British settlements in New England, the Confederacy accepted French fortifications and support. One has to keep in mind, however, that the Wabanaki preferred the French over the English precisely because the French posed fewer threats for several reasons. First, the number of French in Acadia was never as great or as worrisome as the number of English to the south. Second, the Acadien community quickly became a syncretic one, comprising Europeans and Aboriginal peoples whose respective clans intermarried extensively. And while populations merged, so did cultures. By the late 17th century there were many Catholic Mi’kmaqs, perhaps as many as there were Catholic French-Acadiens. The English never made this kind of inroad into Wabanaki society nor did Wabanaki peoples find themselves in English colonial councils.

Third, despite Wabanaki hostility toward New England, Acadia was a trading and seagoing community that often worked with Bostonian merchants. When La Tour’s fortunes were slipping, he sought financial support and muscle from his (fellow Protestant) network in the New England port. Fourth, official French Catholicism in the colonies was not always rigid. Not only did it permit a Protestant governor but it left its people to their own spiritual devices for years at a time. Resident priests were something of a rarity. Besides, the priests/missionaries were often off leading Wabanaki troops against their Protestant English neighbours. Fifth, Acadia had an economy that was integrative and imaginative. Perhaps the highest achievement of d’Aulnay’s career as governor was his support for the draining of the salt marshes, a distinctively Acadien practice that created coastal and river-mouth pasture land on which to raise substantial herds of cattle — without, importantly, alienating Aboriginal land. More than any other governor in New France, d’Aulnay was successful in building a true colony (albeit one that was not entirely French). Finally, despite the horrors of the civil war (and the hangings of the Saint John garrison were especially grisly), the conflict ended with reconciliation: d’Aulnay died and La Tour married d’Aulnay’s widow. This kind of “third-way” resolution was to become a trademark Acadien strategy over the century that followed the war.

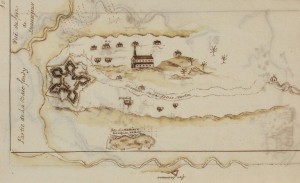

In the meantime Acadia had to deal with its vulnerability issues. Its land and sea frontier to the southwest faced New England and other British colonies and its ocean frontier to the north and east was teeming with fleets of working and naval ships from England/Britain, Spain, Portugal, and still other European countries as well. Much more so than Canada, Acadia bristled with garrisons, from Fort Castine (1615) on the Penobscot River in central Maine east through Port-Royal and Fort Beausejour (1751) at opposite ends of the Bay of Fundy to the heavy-weight Fortress of Louisbourg on Île Royale, built in 1713. The first of these stations came into use early and thereafter often as the growing British and French naval presences in the region increasingly were in conflict. Eighteenth century conflict is considered more fully in Chapter 6.

Acadia and French Newfoundland

The fisheries and whaling grounds around the island of Newfoundland attracted fleets from the British West Country ports, from French harbours like St. Malo, from Portugal, and from the Basque villages on the north coast of Spain. Settlements were slow to emerge, not least because England, for example, wanted to control its fleets and sailors; England (and the other European nations involved in the fisheries and in whaling) regarded the Grand Banks and the Strait of Belle Isle as training grounds for voluntary and involuntary navy recruits. Establishing onshore settlements would work against these priorities. (See Chapter 6 for more on this topic.)

Settlement simply wasn’t necessary: the salting of cod could be performed onboard the fishing vessels. Eventually and perhaps inevitably, Europeans (particularly those with a less reliable supply of salt) began landing their catch on the beaches of Newfoundland and drying the fish there before heading home. This was predictably the response first of those fishing fleets, among them the English, that lacked access to salt. It was this process that drew French sailors to Plaisance, or Placentia, where the rocky beaches were perfect for drying fish. In 1655 the French made it the administrative capital for the half of the island that they controlled and began the process of fortifying the harbour and town in 1662. The French lost this position in the Treaty of Utrecht (1713), but as a port Placentia remained the only rival to St. John’s in Newfoundland for nearly a century more.

Key Points

- The establishment of Acadia marks the beginning of French colonial settlement in North America.

- The French and Acadiens were able to establish good working relations with the Wabanaki Confederacy in part because of a shared distrust of the English and New Englanders.

- The military component of the French colonial experiment existed in both Acadia and Newfoundland.

Attributions

Figure 4.2

Port Royal, Nova Scotia – circa 1612 – Project Gutenberg etext 20110 is in the public domain.

Figure 4.3

Portrait Françoise-Marie Jacquelin by Jeangagnon is in the public domain.

Figure 4.4

The Mi’kmaq by Mikmaq is used under a CC-BY-SA 2.5 license.

Figure 4.5

FortBeausejour1750McCordMuseum by Skeezix1000 is in the public domain.