14.8 Summary

History is a complex dance between continuity and change. Both, however, are deceptive. What appears to be continuity can, from time to time, be the reappearance of a practice or belief, one that had been suspended for a time. A single element of material design might be perpetuated for centuries for reasons that no one recalls except that it works. Historical study teaches that one cannot count on continuity to be anything but slippery, and yet perceptions of the past are more comfortable with simple, slow-moving narratives than fluidity. Keith Matthews, a historian of Atlantic Canada once took his colleagues to task for presenting “Newfoundland’s history as timeless.” He argued that “Although groups changed in characteristics and importance, historians nevertheless perceived eternal and unchanging conflict raging for more than 200 years.”[1]

Who were the people of the new Dominion? Negotiations took place between colonial leaders and ignored Aboriginal peoples entirely, as well as the Métis. As a mechanism for expediting business transactions between colonies/provinces and creating administrative efficiencies, Confederation held out some promise; as a representation of the aspirations of the people across most of the territory to which it laid claim, it must have seemed baffling.

What’s more, the “people” were a moving picture, not a photograph. They were being changed by forces many could not yet see. Industrialization and urbanization were the foremost of these.

In a matter of a few years the typical Canadian life course would include living in growing and industrial cities and working for wages. The majority of Canadians would continue to live on the land for another 60 years, although some provinces would cross the threshold into being principally urban much sooner. In other words, the impression is inescapable that the people for whom Confederation and all its aspects was crafted would soon be overwhelmed by a different society. The extent to which a united British North America would recognize and serve well the interests of those people, those Canadians, is the test that lay ahead in the post-Confederation period.

Key Terms

Charlottetown Conference: Convened by the leaders of New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, and Nova Scotia for the purpose of discussing Maritime Union on September 1-9, 1864; discussed the possibility of a union that would include the Province of Canada. Laid the groundwork for the Quebec Conference.

Council of Assiniboia: An unelected council created by the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1835 for the administration of Rupert’s Land.

double majority: In the Province of Canada, an attempt to break the gridlock under the 1840 constitution by means of multiple majorities: a majority in the 84-seat assembly was required along with majorities in the Canada West and Canada East segments of the assembly (42 seats each) for a bill to pass into law.

double shuffle: The practice under the 1840 constitution that new, incoming cabinet minsters in a government were obliged to resign their seat in Parliament and seek re-election in a by-election. The idea was that electors had a right to acknowledge and approve the change of status in their representative. In 1858 John A. Macdonald took advantage of this rule to vote out George Brown’s temporarily depleted government; he then merely moved his own ministers around — twice — to avoid having to go to by-elections. This cabinet “shuffle” thus became a “double shuffle.”

half-breeds: A term that was once descriptive but soon became pejorative to describe individuals whose ancestry includes both European and Aboriginal elements.

House of Commons: The Canadian House of Commons, modelled on the British House of Commons. Its members (referred to as Members of Parliament or MPs) are elected and the principle of representation-by-population generally prevails. Legislation dealing with expenditures or taxes can only be introduced in the House and the House of Commons has, at the end of the day, pre-eminence over the appointed Senate. The government is, in principle, based on the party that has elected the largest number of members. That party is referred to as the “governing party;” ministers — including the first minister, or prime minister — are appointed from the ranks of the majority governing party and constitute the executive council, or cabinet.

imperial federation: A proposal to restructure the British Empire along federal lines, creating a more equal partnership in place of a colonial relationship. This idea gained a significant and influential following in Canada in the 1880s and 1890s.

medicine line: Reputedly a Plains Aboriginal term for the 49th parallel boundary between the British-Canadian Plains and the American west.

peace, order, and good government: A phrase from Section 91 of the British North America Act, 1867, and sometimes abbreviated to POGG. This is the residual powers section of the Act. Section 91 states that, beyond what is clearly allocated as provincial responsibilities and federal responsibilities, anything otherwise necessary to the “peace, order, and good government” of the country is to be handled by Ottawa.

provisional government: Generally, an emergency or interim administration. In the case of Red River (Manitoba) the government established under Louis Riel’s leadership when the Council of Assiniboia dissolved and before the Canadian administration was able to legitimately seize power.

residual powers: Responsibilities not clearly demarcated and described in the constitution. In a federal system the residual powers typically belong to the central government. This was the intent of Section 91 of the British North America Act.

Senate: The appointed upper chamber of the Canadian Parliament, similar to the House of Lords in Britain. Distribution of seats was intended to be unrelated to population so that each province (or at least each region) would have significant representation. The chief role of the Senate is to review legislation and, where needed, suggest refinements. Because senators do not have to report to an electorate they are, theoretically, free to consider laws without bending to local pressures. It is for this reason that the Senate is sometimes referred to as the “house of sober second thought.”

Seventy-Two Resolutions: Also known as the Quebec Resolutions, the proposals drafted (mostly by Macdonald) at the Quebec Conference in 1864. These were forwarded to Britain where they were further refined at the London Conference of 1866. They formed the outlines of the federal constitution as presented in the British North America Act of 1867.

Short Answer Exercises

- What motivated Canadian politicians to explore a federal arrangement?

- Why were the premiers of the Atlantic colonies interested?

- If federalism was the answer, what was the question?

- What other options were available?

- To what extent was Confederation a British idea?

- What was the role of the United States in advancing the cause of colonial union?

- How did Rupert’s Land figure into the dialogue about Confederation in 1864-67?

- What were the sources of opposition to Confederation? How were they addressed?

- Why did Nova Scotia and New Brunswick both eventually agree to join Confederation?

- Why did Prince Edward Island and Newfoundland elect to stay out of Confederation in 1867?

- What were some of the main features of the proposed federal union?

- What was the response of westerners to Canada’s annexationist move?

- In what ways was Canada in 1867 a society poised on the brink of change?

Suggested Readings

- Ajzenstat, Janet. “Human Rights in 1867.” In Canadian Founding: John Locke and Parliament, 49-66. Montréal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2007.

- Smith, Andrew. “Toryism, Classical Liberalism, and Capitalism: The Politics of Taxation and the Struggle for Canadian Confederation.” Canadian Historical Review 89, no.1 (March 2008): 1-25.

Attributions

Figure 14.10

York Boat by Verne Equinoxis used under a CC-BY 3.0 license.

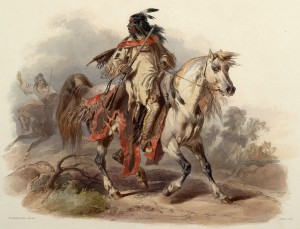

Figure 14.11

A painting from life by Karl Bodmer by El Comandante is in the public domain.

- Quoted in William Gilbert, “Beothuk-European Contact in the 16th Century: A Re-evaluation of the Documentary Evidence,” Acadiensis XXXX, no. 1 (Winter/Spring 2011): 44. ↵