14.5 Atlantic Canada and Confederation

Confederation was, very clearly, an idea arising in Canada as a solution to Canadian problems and it was meant to give advantage to Canada first and foremost. It did not derive from the ambitions of Prince Edward Islanders, nor was it an expression of the dreams of Newfoundlanders. Nor too was it a scheme hatched in Fredericton or Halifax. Our understanding of the outcome of the Confederation discussions must begin with that reality, which raises the question, Why did some Atlantic colonies believe the federal union was worth joining while others did not?

There were vested interests in the East that saw a union of colonies as a route to profit. And to some of those leaders who envisioned the possibilities of a larger and more complex and technological political entity, we can confidently ascribe the title “modernizer.” Their values became dominant in the late 19th and early 20th centuries as modernization was widely accepted as a goal inseparable from the nation state. It is important, too, to recognize that the decision to join in a federal union was made by politicians and not by referendum. Doing so obliges us to come to grips with contrary interests among political elites and between political elites and the people they nominally represented.

Clearly there were different economic agendas at work. One study of Maritime support for Confederation found it to be strongest among those who envisioned a continental and international industrial economy and weakest among those who were at the heart of the established shipping industries of the region. This apparent dichotomy hides the presence of contrary voices on both sides but it should alert us, too, to one of the hoariest myths of Confederation: that is, Maritime opposition sprang out of conservative, backward-looking parochialism. In fact, the shipping industry was a hotbed of innovation and was highly aggressive in its marketplace.[1] Certainly there was new money going into industrial proposals, but that does not necessarily mean it was characterized by youth and vigour while the established elite was being old and unimaginative.

The Maritime colonies approached Confederation from a position of weakness. Not only were their numbers, economies, and assets a fraction of the size of Canada’s, their political vision was not nearly as unified. Canada’s “great coalition” existed precisely because a new constitutional arrangement was needed to get beyond the political impasse in Ottawa. Brown, Cartier, and Macdonald had a lot at stake in their mission, and they were motivated, therefore, to speak with something like a single voice in favour of the structure they envisioned. The same was not true for the Maritimers. In each East Coast colonial assembly there was substantial division and no mandate to reconfigure the whole of British North America. Had they first achieved Maritime union, perhaps they might have stood as one. As it was, Prince Edward Island, to take one example, never had the chance to get past feeling dwarfed by Nova Scotia and New Brunswick before being overwhelmed by the Canadas.

Newfoundland

Newfoundland, for its part, viewed the whole proposition with bemusement if not outright hostility. After all, there was nothing that an island colony across the St. Lawrence Gulf would get from a federal union: no railway, no bridge, and few economic advantages that it did not already enjoy. And the potential costs — loss of political authority to a centre 1,000 kilometres to the west, paying for a railway between Halifax and Montreal, and being dragged into Canadian-American affairs — were too high. A Newfoundland opponent of Confederation famously warned that if Ontario was again under attack from the United States, the national government would call upon the rest of the unified British North America to assist, and the cream of Newfoundland youth would leave “their bones to bleach in a foreign land.” As one historian wrote, “Secure behind a wall of water, the island had its independence guaranteed by the Royal Navy.”[2]

In 1869, after the other colonies had joined as one Canada, pro- and anti-Confederation politicians took their arguments to the electorate. There were other, more immediate, issues before the voters, but the rejection of Confederation was resounding. As the outcome was announced,

…the fishermen and mechanics of St. John’s …put together a large coffin labelled “Confederation,” which was placed on a vehicle draped in black, and this was drawn by scores of willing hands through the town, headed by a band playing the Dead March, and escorted by an immense crowd to the head of the harbour, where a grave was dug below high-water mark and the coffin solemnly interred therein….[3]

Newfoundland continued to seek its destiny in the mid-Atlantic and kept its back turned to Canada.

Nova Scotia

In Nova Scotia there was little solidarity on the topic of Confederation. The ability of the proposed federal government to establish tariffs and run the fisheries was a major hurdle for a seagoing community. As well there was Joseph Howe to factor into the equation. A highly popular political figure, writer, and journalist, Howe had long envisioned Nova Scotia’s future within a more integrated British Empire. He was, however, a strong advocate for railroad construction and may have undermined his own position by whetting a public appetite for lures like an intercolonial railway. The Nova Scotian premier, Charles Tupper (1821-1915), was exposed on other fronts as well. There were issues before the Halifax assembly that were entirely unrelated to Confederation but which drained his support. Seeing that a protracted debate would likely kill the initiative and certain that he would lose an election on the issue, Tupper forced the resolution through the assembly in April 1866.

Howe travelled to London to fight the British North America Act but he received a cool reception. The Act was passed into law. Three months later Howe was premier, Tupper was out, and the anti-Confederates began an unsuccessful campaign to reverse the process.

Prince Edward Island

The hosts of the Charlottetown Conference proved to be the least amenable to the new union, partly because of the terms on offer and partly because of the peculiar conditions of the smallest colony. Talk of a railroad and the threat of American invasion both played poorly in Charlottetown. Much of the island’s economy was oriented toward the West Indies so even the end of reciprocity mattered less to the population than to others in British North America. Also, and unique among the colonies, Prince Edward Island had a land-tenure arrangement dating back to 1767 that put much of the island in the hands of absentee landlords. The Tenant League, a movement formed in 1864 to end absentee landlordism and to avoid paying rents along the way, carried forward the work of the Escheat Party in this regard. This issue was so important that it overshadowed talk of union. Unless the other colonies could speed up the process of dismantling the proprietor-tenant system, Islanders would remain aloof.

The Fenian threat did, however, have an impact on the island. Prince Edward Island was far from the Maine frontier, farther away from New England ports than the vulnerable harbours of Nova Scotia, and mostly insulated from the outside world by a nearly frozen sea. That didn’t stop a Fenian panic from spreading through the colony. It was alleged by the ruling Conservative Party that the Fenians were an enemy within. Careful not to tar all Catholics with the same brush, or to call out all of the Irish settlers on the island (and nearly half of Charlottetown at the time was Irish), the Conservatives used the opportunity to harden Tory sensibilities at the expense of the more Catholic Liberal Party and the Tenant League. The League was branded as disloyal and sympathetic to the Fenian cause. The Liberals called this cynical fear-mongering: “Stripping the militia of its arms, mobilizing the garrison, mounting a citizens’ guard over the Benevolent Irish Society, and generally giving credence to the St. Patrick’s Day panic: all were portrayed as a studied insult, inviting Protestants to suspect their Irish Catholic neighbours.”[4]

In this way the Tories hoped to marginalize the Tenant League without actually attacking them and to create conditions under which the British might be persuaded to maintain a garrison presence for a little while longer. The effect on Prince Edward Island’s attitude to Confederation was mixed. Some felt that, as the British were making an exit, the new federation could offer up its own military presence; others felt it was more likely that a homegrown militia would be called on to defend more vulnerable border colonies. On balance, the threat of Fenian invasion served to aggravate internal discord on Prince Edward Island while adding little to the colony’s enthusiasm for Confederation.

Prince Edward Islanders’ reluctance to join the new federation, then, reflects a lack of “pushes.” There were, as well, few “pulls” that spoke directly to the colony’s needs. The Canadians were not interested in giving the colony special considerations in the federal structure, and Islanders recognized that a small colony with limited resources would soon lose its voice in a larger nation. Continued colonial status and a direct relationship with Britain had some potential, but only if Nova Scotia and New Brunswick stayed out of the new state as well.

After Confederation in 1867, the Islanders found themselves surrounded by this new Canada and its waters. Reality set in quickly and by 1869 Prince Edward Island had abandoned pounds, shillings, and pence in favour of the Canadian decimal system. Their objections that the Seventy-Two Resolutions did not provide enough guarantees for the smallest colony were an annoyance to the other parties in 1864, but by 1870 the Canadians returned with updated proposals. In 1873, they gave Prince Edward Island much of what it had asked for originally, and the colony became a province in Confederation.

New Brunswick

More than any other colony, New Brunswick was being shoved and dragged into Confederation by the issues of Fenians at its doorstep, the loss of protection in British markets, the end of reciprocity, and the promise of an intercolonial railway. The premier, Leonard Tilley (1818-1896), imagined New Brunswick nicely placed as the keystone colony, the only one bordering on three others and the United States. From this position and with a growing economy in Canada, he hoped to craft a thriving trade and traffic. More than this, Tilley — of all the Fathers of Confederation — probably had the most fixed view of the country as one that reached the West Coast. He maintained that the political leaders of British North America should endeavour “to bind together the Atlantic and Pacific by a continuous chain of settlements and line of communications for that [was] the destiny of this country, and the race which inhabited it.”[5] (Tilley was a devout practising low-church Anglican. It is widely thought that it was he who referenced the passage from Psalm 72:8, “His dominion shall also be from sea to sea,” which led to Canada being called the “Dominion.”) Unfortunately for Tilley, New Brunswick voters did not share his vision.

In 1865, in what came as the greatest threat to the Confederation project, Tilley’s government was routed by the anti-Confederation forces in the colony. His opponents seized on the necessary vagaries of the Seventy-Two Resolutions. Where would the railway go? To Saint John, Moncton, or the Miramichi? Or, worse, to Halifax? What would the Ontario Orange Lodge — in the person of George Brown — do to Catholic rights in the federated country? Would New Brunswick manufactures be protected in the new confederated marketplace or swamped by cheap products from Ontario and Quebec? There were other issues that had alienated Tilley’s support; his Liberal party had, after all, been in power for quite a while, his efforts to introduce severe regulation of liquor were divisive, and Albert Smith (formerly an ally, now an adversary and an outspoken opponent of Confederation) was on the ascendant. Tilley lost, Smith won, and the whole Confederation project was in jeopardy. If New Brunswick, the keystone colony, dropped out of the plan, it was doubtful the rest would bind.

Barely a year later, in May 1866, Smith resigned in protest over the highhanded behaviour of Lieutenant-Governor Arthur Hamilton Gordon (who was pressing Britain’s case that Confederation ought to proceed with alacrity). Gordon offered Tilley the government, which he took, another election was called and it served as a referendum on Confederation. Tilley’s restoration was helped along by a timely Fenian raid on the St. Croix River in April and an endorsement from the colony’s Roman Catholic bishop.[6] Even Smith conceded the point. The irony, of course, is that unstable governments were the bane that a changed constitution promised to resolve, but without the instability of the New Brunswick legislature Confederation might not have come to pass at all.

Key Points

- Interest in Confederation in the Atlantic colonies varied and was typically divisive.

- Newfoundlanders and Prince Edward Islanders were not persuaded that Confederation addressed their concerns or that it would in any significant way make them stronger. Indeed, there was a strong sense that Confederation would expose them to new threats.

- Nova Scotia and New Brunswick voters were critical of the proposal.

Attributions

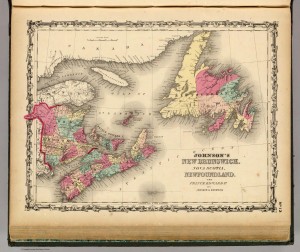

Figure 14.8

New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Newfoundland, and Prince Edward Idis used under a CC BY-NC 2.0

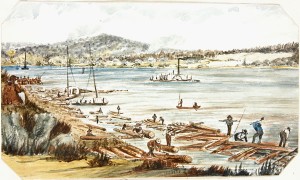

Figure 14.9

Steam ferry boat and rafting timber on St. John River near Fredericton by William Smythe Maynard Wolfe. Library and Archives Canada, Acc. No. 1985-3-70. Copyright expired.

- Phillip A. Buckner, "The Maritimes in Confederation: A Reassessment," in The Causes of Canadian Confederation, ed. Ged Martin (Fredericton: Acadiensis Press, 1990), 103-105. ↵

- Frederick Jones, "'The Antis Gain the Day': Newfoundland and Confederation in 1869," in The Causes of Canadian Confederation, ed. Ged Martin (Fredericton: Acadiensis Press, 1990), 146. ↵

- Quoted in Ibid., 143. ↵

- Edward Macdonald, "Who's Afraid of the Fenians? The Fenian Scare on Prince Edward Island,1865-1867," Acadiensis 38, no.1 (Winter/Spring 2009). ↵

- C. M. Wallace, “TILLEY, Sir SAMUEL LEONARD,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 (University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003). Accessed February 17, 2015, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/tilley_samuel_leonard_12E.html . ↵

- C. M. Wallace, “TILLEY, Sir SAMUEL LEONARD,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 (University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003). Accessed December 4, 2014, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/tilley_samuel_leonard_12E.html . ↵