13.7 Identity Crisis

National histories tend to draw straight and uncomplicated lines. If one of the functions of a national history is to define or distill a national identity, then simplicity is of the first order. Loyalties ought to point in one direction, though occasionally a character in the past may be torn somewhat. But we have come to think of national and ethnic loyalties as instinctive and not all that negotiable. This is part of a tendency to essentialize people in the past: they behave as they do because of what they are in essence.

One of the virtues of West Coast history is the ease with which those narratives may be broken up and thrown aside. People from around the globe collected on the West Coast in the 18th and 19th centuries, in assortments that were, for their time, unique. What’s more, the individuals themselves reveal interestingly complex backgrounds. The ways in which their lives bump up against those of others and then ricochet off in an unexpected direction remind us that stories are not highways but threads that bind and fray.

Take the example of Marguerite Waddens (1775-1860) who was born in Montreal. Her father, Jean Étienne Waddens, was Swiss and a founding member of the NWC; her mother, Marie Josephe DeGuire, was Cree. Marguerite was a product of a fur trade marriage à la façon du pays, a late-18th century métis born in the East.[1] Two of the men in Marguerite’s life would meet their ends in spectacularly violent ways. Her father died at the hands of fellow NWC trader and cartographer Peter Pond when an argument overheated. Marguerite’s first husband, Alexander MacKay (1770-1811) died under even more exceptional circumstances.

MacKay was a child when his Loyalist parents became refugees in the Canadas. Entering the fur trade as a youth, he joined Alexander Mackenzie’s expedition to the Pacific coast (and was thus one of the first Euro-North Americans to cross the continent). MacKay amassed a fortune in the service of the NWC, married Marguerite, and retired to Montreal at 38 a wealthy man — probably without Marguerite. In 1810 the American fur trader and entrepreneur John Jacob Astor (1763-1848) signed MacKay to work with the Pacific Fur Company — an emergent American rival to the British HBC and the Canadian NWC. Sailing on the Tonquin to the West Coast, MacKay was killed along with all but two of the ship’s crew when it stumbled into a political stew in Clayoquot Sound in 1811. Wikaninnish’s fleet made short work of the American crew, killing as many as they could lay their hands on. This may have been one of Wikaninnish’s attempts to obtain a European-style vessel. If so, it failed: perhaps as many as a hundred of the Tla-o-qui-aht raiders perished when a Tonquin crew member detonated the ship’s gunpowder.

Marguerite and Alexander’s son, Thomas, narrowly missed sharing the horrors of the Tonquin because his father chose to leave him behind for a few days at the PFC’s new fort on the Columbia.[2] The widow Marguerite remarried around 1810, which suggests that she had been abandoned by MacKay (a common enough experience for “country wives”). Her new husband was another fur trader, John McLoughlin (1784-1857). Born Jean-Baptiste in Trois-Rivières in 1784, McLoughlin came from Irish immigrant stock (his father) and Canadien ancestry (his mother). Raised by his Scottish uncle, McLoughlin’s spiritual life charted a course from Catholicism to Anglicanism and back. His marriage to Marguerite was not McLoughlin’s first: he was himself a widower, having been married briefly to a Chippewa woman who died giving birth to their son Joseph in 1809.

Within a year of marriage (again, a la façon du pays), Marguerite and John had a son, John Jr. The family continued to grow while they were stationed just west of Lake Superior. During this period McLoughlin senior’s relationship with his stepson Thomas deepened. Indeed both men were at Selkirk in the employ of the NWC during the Battle of Seven Oaks. McLoughlin was even implicated in the killing of Governor Semple, although the charges were later dismissed. He was a key player for the NWC side at the negotiations that led to the merger of the two fur trade giants in 1821.

About seven years later, Marguerite Waddens MacKay McLoughlin relocated with her husband and both sons to the Columbia District where McLoughlin built Fort Vancouver, across the river from Fort Astoria (the PFC base in which Alexander MacKay played a small role). Fort Vancouver was as cosmopolitan as any HBC post and then some. Trade between the Columbia and the Hawaiian (or Sandwich) Islands brought Kanakas (Hawaiians) to Fort Vancouver in large numbers. Trade with Guangzhou occasionally brought Chinese men as crew to the West Coast, and Marguerite’s nephew, Angus Bethune, travelled to China on behalf of the HBC. Marguerite would have been on hand in 1834 when news of three shipwrecked Japanese sailors on the Olympic Peninsula reached Fort Vancouver. Enslaved by the Makah on Juan de Fuca Strait, the three men included a 15-year-old named Otokichi, who — thanks to the intervention of McLoughlin — was brought to Fort Vancouver. Otokichi would go on to play a small part in diplomatic efforts to open Japan to Western trade. (And, like Marguerite, Otokichi’s wide-ranging life would be marked by complete disregard for racial or national categories: his first wife was English, his second Malay.)

Marguerite was well acquainted with James Douglas, McLoughlin’s junior at Fort Vancouver. Born in the British colony of Demerara (Guyana), Douglas had both Scottish and African ancestors. He worked his way through the NWC into the HBC and at 25 years of age he married Amelia Connolly, a métis woman. Shortly after the Douglases were reassigned to Fort Vancouver where James worked under McLoughlin. Douglas observed in these years on the “respect and affection” that McLoughlin held for Marguerite.[3] Douglas grew fiercely loyal to McLoughlin, even against Governor Simpson right up until 1846 at which point their paths diverged. McLoughlin decided to stay put on the Columbia and thus become an American after partition of the Oregon Territory.

John Jr. carried on the family tradition for travel, moving to Paris to take up medical studies. In later years he would acquire a reputation for drunkenness and violence (John Sr. had a temper as well, according to Governor Simpson), which might provide a clue to why he left Paris under a cloud. Difficult to place in the HBC system, he found his way to Fort Vancouver for a spell, then to Fort McLoughlin (on the central coast and named for his father). Finally he was sent to Fort Stikine in the north. There, it was reported, he so terrified his colleagues that one of them shot him through the throat. He died from his wounds at barely 30 years of age.

Thomas MacKay, for his part, had a better record, of sorts. Marguerite’s son by Alexander McKay married well in the Columbia District, partnering with Timmee, the daughter of Chinook chieftain Comcomly.[4] He played a key role in realizing Governor Simpson’s vision of a “fur desert” south of Fort Vancouver, a landscape completely denuded of commercial wildlife so as to block American trade in the region. This war against nature was for naught, as it simply made it easier for American settlers (rather than fur traders) to move into the region.

Not much is known of David, Marguerite’s second son by John McLoughlin, except that he received some training in Paris as an engineer, spent much of his life in the Columbia District, and married a Kutenai woman named Anne Grizzly. Less still is known about John McLoughlin’s son from his first marriage, Joseph, and Marguerite’s three daughters by Alexander MacKay. Marguerite and John’s daughter Marie Eloisa McLoughlin, however, attained some prominence at Fort Vancouver. Born in 1817 at Fort William, Eloisa was educated in Canada and headed west in the 1830s. Young and energetic she took on many of the hostessing tasks that typically would have belonged to her mother. She and her husband opened Fort Stikine around 1841 and narrowly missed overlapping with her ill-fated brother John Jr. at that same location in 1842.

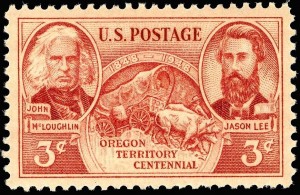

The loss of British sovereignty south of the 49th parallel in 1846 was overseen by McLoughlin, the French-Irish-Scots Catholic-Anglican Canadian who went on to become an American and is celebrated in the United States as the “Father of Oregon.”[5] Marguerite’s final public role was that of mayor’s wife in Oregon City, where the couple are buried side-by-side. The Swiss-Cree Protestant-Catholic mother of seven children and stepmother to another (some of them, like their fathers, Scots-Irish or French or Loyalist), mother-in-law to women drawn from Aboriginal nations from the north coast to Idaho, and aunt to members of the Family Compact in Upper Canada, Marguerite’s life took place on a stage of enormous distances and great risks, one that involved a multitude of actors from across the globe. Tug on any one thread and any number of narratives unfold.

Key Points

- The notion of national or ethnic identities of individuals in the Cordilleran fur trade prior to the 1850s is inherently problematic.

- Canadiens — who were often simultaneously métis — played a key role in what is often mislabelled the British fur trade in the farthest West.

- Remote posts were often connected by the presence of family members and within post communities themselves there was often a dense network of relationships between Euro-North Americans and Aboriginal peoples.

Attributions

Figure 13.20

Oregon Historical Society (OHS) #bb006496. This photo has been released under a CC-BY 4.0 International license by the OHS for this textbook.

Figure 13.21

Fort George by Cropbot is in the public domain.

Figure 13.22

Otokichi by Liftarn is in the public domain.

Figure 13.23

Oregon Territory Centennial 3c 1948 issue by Gwillhickers is in the public domain.

- One of Marguerite's sisters, Veronique, would marry the Rev. John Bethune; two of their descendants are Dr. Norman Bethune (the Canadian physician who achieved legendary status in the Chinese Revolution) and the accomplished actor, Christopher Plummer. ↵

- Jean Morrison, “MacKAY, ALEXANDER,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 5 (University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003). Accessed January 18, 2015, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mackay_alexander_5E.html . ↵

- Margaret A. Ormsby, “DOUGLAS, Sir JAMES,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10 (University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003). Accessed August 7, 2014, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/douglas_james_10E.html . ↵

- Jean Barman, French Canadians, Furs, and Indigenous Women in the Making of the Pacific Northwest (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2014), 131. ↵

- W. Kaye Lamb, “McLOUGHLIN, JOHN,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 8 (University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003). Accessed January 18, 2015, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mcloughlin_john_8E.html . ↵