13.10 A Shrinking Aboriginal Landscape in the 1860s

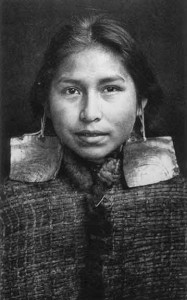

We begin this chapter with a photograph (Figure 13.33) by well known “Native” photographer, Edward Curtis. His work has attracted controversy and criticism because of the way in which he staged each shot to create, in his view, a sense of “timelessness” and lack of progress.[1]

Smallpox, 1862-63

In the spring of 1862 “patient zero” stepped off a ship from San Francisco and into the streets of Victoria, the capital and trademart of the Colony of Vancouver Island. He was carrying smallpox and the harbour was crowded with Aboriginal traders. Rather than quarantine that community and apply the kinds of practices modelled 80 years earlier at Cumberland House (see Chapter 5), the colonial administration ordered the encampments cleared. They sent traders home to their villages up the coast, which proved to be a lethal error. Smallpox travelled with them and claimed about 20,000 lives, virtually all of them Aboriginal. A third to two-thirds of the Aboriginal population was gone almost overnight.

This isn’t merely a statistical note: the psychological trauma can barely be imagined. Kekulis (pithouses) piled high with the dead were simply abandoned and allowed to collapse on themselves; above-ground houses and whole villages were torched in the hope that doing so would halt the march of smallpox. Survivors, particularly children, starved to death with no one left to feed them. There were literally bodies everywhere. One account from the Cariboo gold district describes seeing canoes floating past on the Fraser River, filled with bloated corpses. This was near-extinction for many communities and some of them have never recovered.

Smallpox made subsequent appearances in British North America and post-Confederation Canada, but they were minor events by comparison. The 1860s epidemic was, for once, well documented by newcomers and as a result historians have a good sense of its enormity, particularly for those who survived. In the Pentlatch village on Vancouver Island, there was one survivor. That individual was adopted into the K’ómoks (Comox), a Kwakwakw’wakw band that moved south into the vacuum left behind by smallpox. But the K’ómoks themselves were badly reduced. There was no Aboriginal community in the Comox Valley strong enough to resist the intrusion of newcomers in the decade that followed. The colonists stripped the hillsides of cedars and firs, they opened up the ground and its seams of coal, they claimed the fisheries, and confined the indigenous people to a postage-stamp sized reserve.

The experience of the K’ómoks was fairly typical of events as they unfolded on Vancouver Island and in British Columbia. Smallpox made space. The newcomers were themselves fewer in number than they had been at the height of the gold rush but some were optimistic about colonialism.

The Chilcotin War

The smallpox story continued with the Bute Inlet crisis (also known as the Chilcotin War or Bute Inlet Massacre). Thinking that a road to the Cariboo goldfields from the central coast would save both time and money and would open up new areas for resource extraction, a party of surveyors was sent up Bute Inlet in 1864 with an eye to exploring possible routes. When they encountered some resistance from the Tsilhqot’in (Chilcotin) people, the White surveyors threatened to introduce smallpox. Given the recent plague, this was both a cruel and stupid strategy. The Tsilhqot’in responded by killing 14 road workers and two other Whites in the region. In the colonial capital of New Westminster there was outrage, but it was tempered with concern that “civilized” people should respond to “savagery” with justice, not blind vengeance.

With this event, as historian Tina Loo has demonstrated, the colonialists were defining themselves as representatives of British (not American) values and as bearing the responsibility to create what they regarded as a better society atop what they saw as a declining, irredeemable, and doomed Aboriginal world.[2] The White response to the incident was largely ineffectual until the leader of the Tsilhqot’in party, Klatsassin, and his immediate followers voluntarily surrendered themselves to the commissioner at Quesnel Forks on the understanding they would be treated as prisoners of war. Presumably they hoped to move to a diplomatic phase in the disagreement, but this did not occur. The colonial power arrested the eight men, charged most of them with murder, and hanged Klatsassin, his son, and three others.

These two events — the smallpox epidemic of 1862-63 and the Chilcotin War of 1864 — point to a severe and abrupt reduction in Aboriginal power in the farthest West. But they also point to continued resistance to newcomer authority and newcomer willingness to exert authority through violence. From the perspective of the Tsilhqot’in, a people whose system of justice was traditionally more personal and whose system of government was kin-based, the very concept of a state that would seek out and execute people in their own territory who were, in their minds, guilty only of protecting that territory, could hardly have seemed more alien. The repressive laws that followed — restrictions on where Aboriginal peoples might live and what land they might own (the reserve system) — was only possible because of the epidemic. And it was made necessary (as the colonialists saw it) by the potential for violence and disorder on the part of the people whose lands were being seized.

The execution of Klatassin and his son Pierre, is conspicuously inconsistent with the character of Aboriginal-newcomer relations in the early part of the century. There were, to be sure, instances of gunboat diplomacy in earlier decades but the colonists’ discourse surrounding the Chilcotin War was one of conquest, not co-existence. Newcomers took full advantage of the space cleared by smallpox and reserves in the late 1860s. The colony, however, remained a nervous place. For Aboriginal people the fear of smallpox, measles, whooping cough, and other diseases, as well as the armed might of the newcomers, made them more receptive to the blandishments and promises of missionaries and government officials.

Missionaries on the Mainland

Missionary work across most of British North America until the mid-19th century was conducted by Catholics. The rise of the “non-conformist” denominations changed the landscape in Canadian and Maritime towns. In British Columbia, however, there was a missionary stampede to compete with the gold rush.

Unofficially, the HBC regime favoured the Anglican Church and it was clearly preferred among the colonists. In the missionary field, however, the Anglicans faced the forces of the Oblate (Catholic), Methodist, Presbyterian, and even Salvation Army missionaries (although this last group did not arrive on the scene until after Confederation). The governors who succeeded Douglas — Seymour for the mainland, Arthur Edward Kennedy (1809-1883) for the island, and Musgrave for the united colony — were tolerant of all sects in terms of their mission activity. Their reasoning was that more missionaries meant a greater likelihood of “peace and order among the colony’s Natives.”[3] Put in other terms, missionaries brought acceptance of the new colonial regime and compliance. The message of peace was not, however, consistently modelled by the missionaries. Competition broke out between the clergymen and accusations of poaching were not infrequent. Aboriginal groups were subjected to one largely intolerant version of Christianity after the next. In more than a few instances, however, Aboriginal peoples sought out missionary support.

Oblates set up chapels throughout the interior of the colony but, in most locations, priests came by only infrequently. Enthusiasm for the latest missionary was, therefore, easily dissipated. In the case of the Nlaka’pamux at Lytton, their relationship with the Oblates soured when the itinerant Catholic clergy demanded control over the chapel; the Nlaka’pamux believed it was their property. The Oblate neglect of Lytton and their misunderstanding of Nlaka’pamux notions of ownership resulted in the band rejecting one set of missionaries and seeking out an Anglican alternative.[4]

As was the case with Duncan and Crosby on the island and on the north coast, Interior missionary activity was usually predicated on an Aboriginal welcome. Those looking for explanations for the cataclysmic experiences they were witnessing turned to ministers who claimed to have answers. Aboriginal spirituality, moreover, was not monotheistic, so a European belief system (or elements of it) could be grafted on to traditional ideas. Missionaries, perhaps more than anything else, could function as cultural intermediaries. Throughout the fur trade era Aboriginal protocols applied; almost overnight British civil and criminal law was being enforced across British Columbia and up and down the coast as well. A resident cultural interpreter who might also provide some English language training was viewed in many communities as an asset.

These were transformational days indeed. The naval base at Esquimalt tilted the power balance definitively toward the newcomers, at least on the coast. In the Interior, “Hanging Judge” Begbie was able to stifle Aboriginal resistance and enforce conformity to colonial law. As the populations thinned, these executions had greater and greater impact. One historian, Jean Barman, has described the policing of Aboriginal women’s morality on the streets of Victoria in the 1860s. Viewed as sexually “transgressive,” they were characterized as prostitutes and treated as such by the colonial legal system. More than that, their reputation (earned or not) made them useful bait in newcomer-run dance halls (where miners and dockworkers could be parted from their money) and in the pulpit (where clergymen could rail on about the moral dangers of frontier life).[5]

The 1860s saw, as well, continuing decline in the acceptance among non-Aboriginals of intermarriage. Prominent women like Lady Amelia Douglas, who grew up speaking Cree (her mother’s language) and Canadien French (her father’s), was only 16 when she married a rising HBC trader. In her dotage she would be exposed to the pearl-clutching racist snobbery and outright racism of settler society, despite being the late governor’s widow. The advent of prejudices of this kind paved the way for the marginalization of Aboriginal people generally in the last quarter of the 19th century.

Key Points

- The 1862-63 smallpox epidemic claimed one- to two-thirds of the Aboriginal population in British Columbia and Vancouver Island, significantly reducing the ability of the indigenous peoples to resist further colonial intrusion.

- Efforts at resistance continued, as in the Chilcotin, but these were met with executions of the leadership.

- The process of cultural change imposed by the colonial regime took many forms, including missionary Christianization, Western-style education, new land-ownership strategies, stripping of resources, and the application of a foreign judicial system.

Attributions

Figure 13.33

A Kwakwaka’wakw girl wearing abalone earrings and a cedar bark cloak by Magnus Manske is in the public domain.

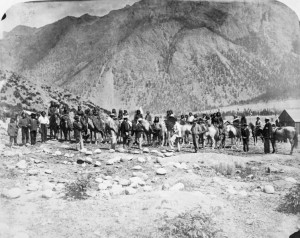

Figure 13.34

Charles Gentile-Lillooet Indians by Themightyquill is in the public domain. This image cannot be used for commercial purposes. It is available from Library and Archives Canada under the reproduction reference number C-088930.

- See Margaret B. Blackman, "'Copying People': Northwest Coast Native Response to Early Photography," BC Studies, 52 (Winter 1981-82): 104. ↵

- Tina Loo, "The Road from Bute Inlet: Crime and Colonial Identity in British Columbia," in Essays in the History of Canadian Law, vol.5: Crime and Criminal Justice, eds. Jim Phillips, Tina Loo, and Susan Lewthwaite (Toronto: Osgoode Society, 1994), 112-42. ↵

- Brett Christophers, Positioning the Missionary: John Booth Good and the Confluence of Cultures in Nineteenth-Century British Columbia (Vancouver: UBC Press, 1998), 10-14. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Jean Barman, "Aboriginal Women on the Streets of Victoria: Rethinking Transgressive Sexuality during the Colonial Encounter," in Contact Zones: Aboriginal Women and Settler Women in Canada's Colonial Past, eds. Katie Pickles and Myra Rutherdale (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2005), 205-227. ↵