13.1 Introduction

Historical approaches to British Columbia follow imperial avenues. From a Canadian perspective, we approach it along the routes of the North West Company (NWC), through the northern Rockies and along valleys and passes to Bella Coola or the Columbia River. From a British or Spanish perspective, we come at it from the sea and from warmer waters to the south, perhaps via Hawaii. Had Russia successfully annexed everything on the West Coast, the historical approach would reflect that northern intrusion — a story of Siberian traders from Kamchatkan ports, incrementally working their way from Alaska to California. An American imperial approach focuses on the mainland, specifically on the Oregon Trail, though it should make room as well for the multitude of entrepreneurial Bostonian captains sailing around Cape Horn on long-haul trade expeditions. The American view would also observe the enormity of Washington, D.C.’s claim on the territory and the impact of Americans throughout the gold rush years.

Once it was determined to the satisfaction of Europeans and Euro-North Americans that there was no water passage through the territory, they started to think of it in terms of ports, coves, forts, and corridors. What is missing from these competing imperialist views is an appreciation of the region as a human space, a dense patchwork of cultural territories for which “getting in” and “getting out” are irrelevant concepts.

Historian Jean Barman coined the phrase “the West beyond the West” to describe the territories that would eventually coalesce into British Columbia by 1871. Other terms that have been used include Trans-Mountain West, the Cordillera, New Caledonia, New Albion, the Pacific Northwest, and Cascadia (this last one lumps together British Columbia with the American states of Washington and Oregon). None of these labels are perfect, not least because British Columbia covers such a vast territory, one that includes the prairie lands of the Peace River District in the northeast, the rolling and almost pastoral Cariboo plateau, and the desert and semi-desert terrain of the Okanagan and Thompson Valleys, as well as the mountainous landscape throughout and the fjords and islands of the coastlands. Much of the region is as unlike the “Pacific Northwest” as can be imagined. More to the point, British Columbia is, with the exception of the Peace District, utterly separate from the Prairies. For that reason, Barman’s “West beyond the West” works nicely to remind us that there is a whole world of regions within a region that lies outside the more easily conceptualized prairie landscape we refer to simply as “the West.”

The period from 1740 to 1874 in the farthest west was a time of Aboriginal cultures adapting and adopting European and Asian technologies and matériel successfully. It also encapsulates a catastrophic loss in populations brought on by epidemics of exotic diseases. While European and American merchants struggled to find the sweet spot in a fur trade with potentially enormous profits but very high costs, Aboriginal communities found themselves confronting internal competition and conflict as well as gunboat diplomacy. European impact on the region was, nevertheless, limited until the 1858 gold rush, at which point the local contact period accelerated very suddenly and in ways unseen elsewhere in British North America. Combined with the arrival of an industrial revolution, these changes drove significant political changes at a record pace. There was no “pioneer stage” in the West, just a race to industrial scales of production that began in the Victorian era and overshadowed nearly a century of regional commerce. Toward the end of this period, a single colonial regime had emerged along with many familiar themes associated with power and elitism. Throughout it all, Aboriginal people took a stand against the newcomer populations and cultures (in the 1860s in particular), and many of the issues they addressed then remain unresolved in the 21st century.

Learning Objectives

- Broadly describe regional Aboriginal cultures and their differences.

- Explain outsider interest in the region from 1740 to Confederation.

- Describe some of the advantages and disadvantages held by, respectively, the Russians, the Spanish, the British, and the Americans.

- Demonstrate an understanding of Aboriginal autonomy and resistance from the 18th century through the 1860s.

- Explain the colonial administrations’ approach to Aboriginal peoples.

- Describe the economies of the two West Coast colonies.

- Account for and describe the social and political fracture lines in the region.

- Describe and comment on the gold rush and its effects.

Attributions

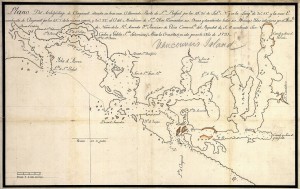

Figure 13.1

Plano del Archipielago de Clayocuat 1791 by Pfly is in the public domain.