12.7 Children as Historic Actors

To what extent is it possible to think of children in past centuries as having agency in their own lives? Feminist historians have corrected the widespread misconception that women were mere shadows in the past; historians of First Nations have likewise shown that Aboriginal people were actors and not merely acted upon. Post-colonial and feminist critiques have moved those goal posts — can the same be done for the history of childhood?

Certainly children faced constraints in past societies. Paternal authority in law was unquestioned in both French and English civil and common law; children had no independent rights whatsoever. What’s more, as property, they were able to be reassigned to other owners, whether temporarily (as in the custodial care of an orphanage) or permanently (as in “binding” as an apprentice to a master or to the navy). Children who had become impoverished and thus dependent on the state or parish could be bound by either to an employer/master. In instances like these the permission of parents wasn’t needed. For the least fortunate in Upper Canada, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, New Brunswick, and Newfoundland, the British Poor Laws applied. Boys and girls were mixed in with adults of all ages in circumstances that provided them little in the way of safety from harm. An 1832 inquiry into the Halifax Poor Asylum revealed “that the seventy-four orphan children in the institution slept with adults ‘without any regard to fitness of health or morals.’” Conditions did not improve in a hurry: in 1849 it was discovered that boys and girls — some as young as eight years old — were regularly whipped with rawhide while incarcerated at the Kingston Penitentiary.[1] There is no doubt, then, that children were vulnerable and frequently exploited and harmed.

But that is not the same thing as being powerless or without influence. The discourse around the rise of “street arabs” is clear about one thing: urban adults felt menaced by children. That is not to say that street children were a force for chaos and danger, but that they resisted the self-appointed moral authority of the state and adults. Faced with dangers themselves, children often found strength in groups of peers and they resisted institutionalization. They fled and taunted; they spoke up for one another. Solidarity occasionally occurred.

Perhaps the most compelling evidence of childhood agency comes not from the emerging cities of the early Victorian era but from Wendat society before the Confederacy’s disruption in 1649-50. Ceramics was an important part of the cultural and artistic life of the Wendat. As a non-nomadic farming people, the Wendat had both the capacity to store large numbers of ceramics and had many uses for containers. Ceramic production was, therefore, a central part of village life. An archeological study from 2006 demonstrates that children were involved in the making of pottery variously known to scholars as “juvenile,” “baby,” or “toy” ceramics. “These small ceramic vessels are … categorically different, in formation and design from the typical, widespread ‘adult’ pots.” What a careful examination of these artifacts reveals is that children were not merely learning the art of ceramics: they were introducing stylistic change.[2] Childhood creativity, invention, and innovation were forces for change within pre-contact Wendat societies and, we can safely assume, in all those societies that followed.

Attributions

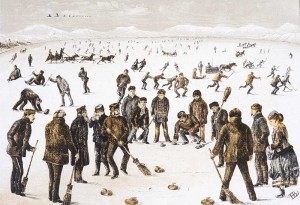

Figure 12.4

Curling on the lake, near Halifax, N by Library and Archives Canada is used under a CC-BY 2.0 license. This image is available from Library and Archives Canada under the reproduction reference number C-041092.

- Robert McIntosh, Boys in the Pits: Child Labour in Coal Mines (Montréal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2000), 29-30. ↵

- Patricia E. Smith, "Children and Ceramic Innovation: A Study in the Archaeology of Children," Archeological Papers of the American Anthropological Association 15 (2006): 65. ↵