11.1 Introduction

Admiral Horatio Nelson, the victor of the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805, was memorialized shortly after his death by pedestal columns erected around the empire. The Nelson Monument in Montreal was the first in British North America and elicited different reactions from the Anglo-Protestants and the French Catholics. Completed in 1809, the column provides Nelson with a good view over the city, is visible for miles, and functions as a daily reminder of the triumph of British naval (and commercial) power both across the Atlantic and in North America. At 69 feet tall, it is not the tallest of the Napoleonic Columns (the one in Trafalgar Square in London stands 170 feet high), and Brock’s Monument is taller still.

The first memorial to General Isaac Brock was erected on the Niagara River at Queenston Heights in the 1820s, when the War of 1812 was still very much a recent memory. It originally stood 135 feet tall and was easily visible from the American side of the Niagara gorge. The column — with a viewing platform at the top — became a pilgrimage site for Upper Canadians. For Tories it had a special meaning as the place where, at the cost of Brock’s life, the American invaders were repelled. In the budding myth of English Canadian nationhood it would mark the spot where the new nation bloodied its neighbour’s nose. The fact that the Canadian militia was a tiny and reluctant fraction of the troops involved was neither here nor there; growing the legend of loyalism and duty was the point of the exercise. This narrative was perpetuated in song in 1867 by Alexander Muir (1830-1906) in “The Maple Leaf Forever,” often regarded as Canada’s first national anthem. In the second verse, Muir wrote:

At Queenston Heights and Lundy’s Lane,

Our brave fathers, side by side,

For freedom, homes and loved ones dear,

Firmly stood and nobly died;

And those dear rights which they maintained,

We swear to yield them never!

Our watchword evermore shall be

“The Maple Leaf forever!”

Muir was a Scottish immigrant whose father could not possibly have stood firmly or any other way alongside Brock. Setting that literary exaggeration aside, what Muir wished to convey is that Canadians in 1812 had fought for freedom from American republicanism while protecting their families from a savage Yankee attack.

In part, Muir was reflecting his own experiences. At 45 or 46 years of age, he was a member of the Queen’s Own Rifles, a Toronto regiment that served in 1866 at the Battle of Ridgeway, the year before both Confederation and his writing of “The Maple Leaf Forever.” Ridgeway is barely a day’s march south of Queenston Heights, on the same Niagara frontier that Brock defended successfully 50 years earlier. For Muir, a loyal Orangeman and a proud Scot, fighting the Fenian Invasion of 1866 was a matter of saving Canada from the barbarian Irish and Irish-Americans, and as far as he was concerned Brock had done nothing less in 1812.

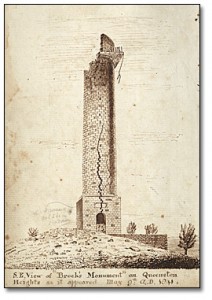

Not everyone felt the same way. To some, Brock was representative of the haughty and corrupt Family Compact, the Tory cabal that wrapped itself in the flag of loyalism and exploited an extensive system of patronage for its own gain. Repeated efforts were made to achieve political reform through peaceful means, but they failed on every occasion. Opponents of the regime were expelled from the colony; some were imprisoned. In the 1830s republican sentiment in the colony was growing and exploded in a brief and doomed rebellion. The rebels who weren’t captured, imprisoned, or hanged were driven across the border into the United States. In 1837 some made their way to Navy Island in the Niagara River, in Canadian waters. They declared a provisional Canadian Republic and plotted, unsuccessfully, an invasion. One of the armed exiles was an Irish-Canadian named Benjamin Lett (1813-1858). As the rebel movement lost steam in 1840, someone — many believed it was Lett — set off an explosion that tore the top off of Brock’s Monument.

The decapitated and ruined tower was transformed in an instant into a very different memorial. Its shattered profile became a powerful testament to the tensions that existed in Upper Canadian society between those whose history was bound up in anti-revolutionary Loyalism, oligarchical authority, and the power of the local garrisons on the one hand, and those colonists who saw themselves as North Americans first, heirs to a tradition of relative colonial autonomy, advocates for democracy, and even foes of the monarchy.

A new monument to Brock was completed in 1860. At 184 feet, it is comfortably taller than Nelson’s Column in Trafalgar Square, making it the tallest of all the Napoleonic Wars towers. It would have been six years old during the Battle of Ridgeway, and there’s some possibility that Alexander Muir passed within view of it as his regiment marched south to face the Fenians. Perhaps he saw it again as his unit retreated in haste after the first volleys near Fort Erie. The Queen’s Own Rifles were mocked by their peers as the “Quickest Out of Ridgeway,” but they faced a force of Irish-American nationalists hardened by three years of Civil War service. The battle cost the lives of 32 Canadians and was an embarrassment for the authorities in Canada West, even though the Fenians abandoned the attack. In other words, it was no Queenston Heights and there were no retroactive attempts to mythologize it.

Among the embarrassed parties after Ridgeway was the Minister of the Militia, none other than John A. Macdonald (1815-1891). Macdonald was then a young and inexperienced militiaman (not unlike the composer Muir). He was visiting Toronto from Kingston and was called up to disperse the rebels led by the radical reformer William Lyon Mackenzie (1795-1861). It is possible that the future prime minister even exchanged fire with Benjamin Lett, who may have been present among the rebels during the Battle of Montgomery’s Tavern.[1]

In the 20th century Canada acquired the epithet, “the peaceable kingdom.” As we’ve seen, the period up to 1820 was marked by anything but peace. The historical record bulges with accounts of inter-empire warfare, ongoing battles between the Aboriginal occupants of North America and newcomers everywhere from Newfoundland to the West Coast, and struggles between settler societies. There were also violent conflicts between British North Americans, such as the fur trade wars and anti-Irish riots. If we think of the Niagara River as the sharp edge of Canadian-American relations, there were three occasions when blood was shed there in the half-century between 1812 and Confederation — once for each of three generations. What happened along the Niagara frontier consistently involved questions about Britain’s relationship with its colonies and where power resided in the colony itself. And, of course, each struggle pointed to the challenges inherent in British North America’s relationship with the United States, one of many important issues that drove political debate in the 19th century.

This chapter places the critique of the established oligarchy in the context of larger political changes taking place across the Atlantic world. The protests that led to rebellion, bloodshed, the Durham Report, the Act of Union, and a nascent Canadian political culture are examined, as are the changes and continuities to be found in the Atlantic colonies.

Learning Objectives

- Learn about the political culture and climate in British North America from 1818 to 1860.

- Identify the major ideological threads running through British North American political culture.

- Describe the principal institutions of power in this period.

- Describe what “reform” meant in the context of the 1820s and the 1830s, and how it changed.

- Detail the main features of the constitutions of the colonies.

- Comment on the changed political role of Aboriginal peoples and how they were perceived by Euro-Canadians.

- Explain the goal and meaning of responsible government.

- Illustrate how ostensibly non-political factors — immigration, cholera, urbanization, debt, sectarianism, etc. — contributed to rising calls for rebellion and an overthrow of the old oligarchical order.

- Critically assess the external forces affecting the political climate.

Attributions

Figure 11.1

Monument Nelson Montreal by Jeangagnon is in the public domain.

Figure 11.2

Brocks Monument by YUL89YYZ is in the public domain.

Figure 11.3

1st Brock’s Monument damaged by pload Bot (Magnus Manske) is in the public domain.

- The fact that Macdonald was exchanging fire with the grandfather of future prime minister William Lyon Mackenzie King is worth considering as well. ↵