10.6 Social Classes

The social classes of British North America at mid-century were a mix of old and new elements. The seigneurs of New France survived into the 19th century, their ranks inflated by the arrival of British gentry who bought up seigneurial titles and lands. And, of course, seigneuries depended utterly on the perpetuation of feudal relations with censitaires. It wasn’t until 1854, with the passage of An Act for the Abolition of Feudal Rights and Duties in Lower Canada by the now-united Province of Canada, that the system truly began to disappear. It would take another 80 years before it was wound up completely, but 1854 marks the beginning of the end of feudalism in British North America.

The seigneurs and censitaires had roots that ran deep into the history of New France, as did the merchants (or burghers or bourgeois) whose claims to legitimacy might go as deep as the fur trade. The seigneurs retained importance politically and socially, but it was the merchants who emerged in the 19th century as the leading social class. By the 1820s, liberal professionals were beginning to make a significant appearance (especially in the towns and cities), and throughout this period the clergy were effectively a social class in their own right, one with considerable clout in all colonies.

Farmers and artisans remained, by far, the largest social category, but by the mid-19th century their numbers were being challenged by a growing working class, or proletariat. (The latter became more organized and significant in size only after Confederation.)

Self-awareness or class consciousness is what makes social classes matter. Not all of these social classes were able to act with a singular will, although their interests were often quite clearly distinct.

Exercise: Documents

Fashion plates

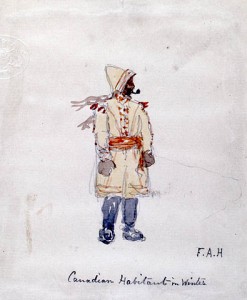

One of the features of vernacular (or folk) culture is that it is slow to change. Below are five visual records of the clothing styles of Canadien men and women in the 19th century (Figures 10.E1 – 10.E5).

To what extent are they durable? What changes do you notice? What elements stand out?

All of these illustrations were made by Anglo-Canadians or British army personnel. What do you think they saw when they looked at their subjects?

The Clergy

While it is the case that the clergy shared a common identity, this identity was fractured by denominations. There was much more solidarity in Lower Canada (Canada East) where the Catholic clergy was tightly organized, engaged in a wide range of social and educational services that went far beyond the saving of souls, and — perhaps most importantly — was aware that their sect existed at the sufferance of the British-Anglican imperial establishment. Belonging to an organization that had these qualities was attractive to many Canadiens, not just as members of congregations but as people seeking a career. Whether in nursing or education, ministering to the poor, serving as missionaries among the Aboriginal population, or working as far afield as the Prairies or the West Coast, the Catholic church offered career opportunities for men and women alike that offered social status, influence, a community of peers, a sense of inclusion, security from cradle to grave, a chance to travel, and a role in protecting and advancing the culture of the Canadiens. In this respect Lower Canada was distinct from France: there, the nobility and the clergy had lost much of their influence during the Revolution, while in Canada they still enjoyed prominence and respect.

The situation for clergy in the Anglo-Protestant colonies was different. Sectarianism was loaded with meaning and sometimes vitriol. The Anglican establishment in Toronto, led by the Reverend (Bishop from 1839) John Strachan, represented the elite, the English, the Crown, and Toryism and took the form of the Family Compact. They regarded Methodists with suspicion and the Presbyterians hardly less so. In 1820 the Family Compact was able to institute a body for managing the Clergy Reserves, one-seventh of the public land. All of this land and the profits from its sale was claimed by the Church of England. Opposition to this arrangement grew through the mid-19th century, and in 1824 the Church of Scotland (the Presbyterians) won a share of the Clergy Reserves, but it remained outside of the local power structure and was a factor in the 1837-38 Rebellions.

William Lyon Mackenzie (1795-1861), a Presbyterian, aligned in his legislative career with Egerton Ryerson (1803-1882), a prominent Methodist minister in Toronto, in pursuing equity of the Clergy Reserves. Mackenzie was reputedly strongly influenced by the anti-clerical views of his mother, Elizabeth Mackenzie, and he was a lifelong advocate of the separation of church and state as a result.[1]

Competitiveness among the various sects was evident in some of the other colonies as well. In Newfoundland, outports were generally defined by the presence of one or two churches to the exclusion of other denominations, but in Prince Edward Island, rivalries between denominations appeared within individual villages. Island Presbyterians, Anglicans, Catholics, and Methodists found themselves squaring off against Congregationalists and Baptists. Each sect offered up larger and larger village churches as a sign of their competitive strength. By mid-century, the Tories on Prince Edward Island had become the party of Protestantism while the Liberal opposition spoke for Catholics and some of the smaller denominations.[2]

Elsewhere in the Maritimes sectarian distribution reflected waves of immigration and movement. Catholicism followed the Acadians back to Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, and it was reinforced by the arrival in Cape Breton of Highland Scots and everywhere by Irish immigrants. Presbyterianism came with the Lowland Scots, and Congregationalism — a vestige of the New England Planter migration in the 18th century — was a minority sect in the 19th century mostly found in New Brunswick.

The end effect of this plurality in Atlantic Canada was to weaken claims of primacy by any one sect. This made it impossible, however, for the colonies to avoid sectarian disputes such as those associated with the funding of schools. And sectarian education, of course, made the imposition of a single curriculum impossible.

Generally, the clergy enjoyed significant social status and influence, in both the French and English areas. The Catholic establishment in Lower Canada had an infrastructure that must have been the envy of other denominations. But religious identity was just as important to Anglo-British North Americans. Sometimes this was tied to ethnicity — such as Scottishness and Presbyterianism or Welshness and Methodism — but more broadly denominational commitment was associational. That is, it was akin to belonging to an exclusive club, one that had its own history and heroes and took care of its members in this life and the next. Robert Barry (ca. 1759-1843) provides one example: press-ganged into the British Navy at no more than 15 years of age, he jumped ship in New York, joined a local Methodist chapel, and was part of the Loyalist migration to Nova Scotia in 1783 where, as one biography has it, “his promotion of Methodism…aided his integration into the pre-existing mercantile structure through select business ties.”[3]

The Capitalist Class

The merchant elite of the Canadas and the Maritimes may have been competitive in their business dealings but they soon recognized a common cause in many aspects of business. And, of course, they were united by Anglicanism, Toryism, and language (English). As early as the 1820s, capitalists had achieved a degree of hegemony in the English-speaking colonies. Being Tory, Loyalist, patriarchal, and hierarchical were the dominant values, largely by default. There was no nobility (other than the governors) or local aristocracy to challenge them from above, the Presbyterians were increasingly onside, and there was not yet a large enough class of artisans or industrial workers who might generate a viable critique of emergent Canadian capitalism. Farmers, smaller entrepreneurs, and urban professionals (discussed below) had something to say about this situation, as did some journalists, but there was a line to be toed and it was drawn by the well-to-do bourgeoisie of Toronto, Montreal, Quebec, Halifax, and Saint John.

The leading spokesmen of this class were, of course, men. However, their web of connections points firmly at female networks that were every bit as important and sometimes gave the men upper-class pretensions. For example, James McGill (an Ayrshire-born son of a metalworker) arrived in post-Conquest/pre-Revolutionary Montreal, entered the fur trade, and promptly married Marie-Charlotte Guillimin (1747-1818), whose father had been a member of the Sovereign Council of New France and a judge in the Courts of Admiralty, and whose maternal grandfather was a giant among the seigneurial class. Sarah Vaughan (1751-1829) fell on very hard times at the end of the Revolution and fled to Montreal as a propertyless Loyalist, where she met, cohabited with (for 15 years), and finally married the brewing magnate, John Molson. Molson himself came from gentry stock in England but Vaughan’s family included the 1st Earl of Lisburne and the Duke of Atholl. Another example from Montreal is Marie-Marguerite Chaboillez (1775-?), the daughter of a leading fur trade marchand who was a founder of the exclusive Beaver Club and who married the Scottish fur trader Simon McTavish. Insulated by wealth and borrowing some of the glow from relatives’ titles and accomplishments, the capitalist elite formed an almost impregnable leadership class in the main towns of the colonies.

However much the merchants and leading manufacturers wished to cast themselves in the mould of “old money,” they were North Americans as well and they endorsed hard work and determination. As one study puts it, “Profit, loss, extensive growth, efficiency, and a myth of individualism pervaded the Canadian economy and the Canadian political scene….”[4] There were enough examples of self-made men in the ranks of leading capitalists — Alexander Keith (a brewer), John Redpath (construction and sugar), McTavish and McGill (fur traders) — to give substance to the notion of individual accomplishment through hard work. These values became deeply embedded in the Canadian culture, reinforced by Britain’s turn to laissez-faire capitalism, the rise of American capitalism south of the border, and a Protestant clergy whose views were not wholly dissimilar.

The Agrarians and Artisans

Farming was the bedrock of the colonial economies of the Canadas, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island. Farming mattered in Nova Scotia as well, but as was the case in Newfoundland, the fisheries continued to exert more power there.

The relationship of farmers to the rest of society was complex. Under the model of the independent farm, a household invested labour and its capital in order to maximize production, making the most of an environment in which winters arrived earlier and left later than in American grain belts. In Upper Canada and in New Brunswick, the farming frontier was organized around townships, which became places of interaction, commerce, stockpiling grain output, and combining to improve infrastructure. The surrounding towns were also where artisans associated with agrarian society located: shoemakers and dressmakers served basic consumer needs, and ironmongers and blacksmiths contributed to the success of farming. In the agricultural monoculture of wheat that existed in Upper Canada (Canada West), competition with other producers was largely meaningless: when everyone grows wheat, everyone hopes for the same rising tide.

For artisans, being a member of a craft signified a degree of structured and regulated training. Stonemasons, for example, were part of a tradition of builders arising out of the Middle Ages who trained as child apprentices, became journeymen, and eventually achieved the status of master craftsmen. They might belong to a guild or an association that limited the number of craftsmen in the market at any time, thereby assuring a reasonably good income. They were mostly independent workers, hiring themselves out on contracts, not as wage labourers. They often had their own shops although some were itinerant.

Shoemakers are among the best studied artisans of the time. They had a strong collective identity, celebrated annually on October 25 during marches for St. Crispin, the shoemakers’ patron saint. As early as 1830 the shoemakers of York (Toronto) organized and went on strike for higher prices, which were locally regulated. According to one study by Greg Kealey, there were 68 shoemakers in the city in 1833 and 49 shoe shops (which may have combined retail with the manufacturing processes) in 1846; by 1851 there were two “shoe factories.” Montreal shoemakers, however, dominated the trade for many decades and were the first to see their work broken into components: women assembled the leather from home, and men added the soles in small shops. Eventually the process was brought under one roof where the newly invented sewing machine was introduced.[5] Again, this part was women’s work: less skilled, lower paid, and more aggressively supervised.

The 1861 census of Canada West tells us that there were 221 boot- and shoemakers in the eastern districts of the colony. Of those, 141 were independent, typically working from their homes or a nearby shop. The work was slow and hard: a single shoemaker was unlikely to complete more than 150 pairs in a year. As the population grew at mid-century, so too did demand for shoes. The factories responded by expanding output which, at the same time, increased pressure on the producer-artisan in the small towns. An advertisement in the Halifax Citizen newspaper of February 20, 1864, called for “20 Workmen on Pegged Work” for the Truro Boot & Shoe Factory.

The effects of industrialization were being felt by the crafts far beyond the big cities. One of the factors necessary for this change was the rise of the dairy industry and beef cattle farming. A shortage of cowhide and tanneries would doom the shoemaking business, so an ecology of supply and demand had to evolve to sustain both the early and the industrialized operations. (In this way, shoemaking also encouraged the cheese business.) Of course, advancements in transportation meant that shoe leather could be obtained from American sources too, especially at mid-century under the terms of reciprocity. With supplies secured and a post-reciprocity market guaranteed, one of the largest operations in British North America, Sessions, Carpenter and Company in Toronto, employed 250 men, women, and children on the eve of Confederation.

In this way, craftsmen’s work became proletarianized. Even if skilled artisans were needed to complete the final product, the division of labour now included children and women, with as much as a third of the workforce in the largest factories being made up of women. Unionization would follow early in the post-Confederation era in an attempt to win back what had been lost in terms of control of work and incomes by the shift from craft to industry.

The transition from craft to unskilled sweated labour was even more rapid in the production of textiles. Montreal was the centre of clothing production business by the 1820s and 1830s. A business that had been dominated formerly by tailors and seamstresses became centralized in early factories where ready-made clothing was produced in large quantities. This entailed, again, a division of labour that supplanted skilled artisans with lower-paid women, men, and children. And according to one study, it did more than disrupt the existing generation of artisans: by dismantling the system that sustained the apprenticeship and journeyman system, it severely impacted the survival prospects for the trade as a whole.[6]

The Middle Classes

As farm families accumulated money from land speculation and wheat production, some were able to advance their position in society. Likewise, some artisans shifted from being independent producers of goods or services to hiring others to play that role: shoemakers grew from being small-shop cobblers to running small- or medium-sized shoe factories; blacksmiths produced a range of agricultural tools, not just horseshoes. As well, a generation of fur traders who, if they had survived the fur trade wars, settled into communities across British North America as people of comfortable means.

As colonial administrative structures became more complex to meet the needs of growing and changing populations, there were opportunities in a very broadly defined civil service. Similarly, as financial institutions became larger they produced opportunities for regional and branch managers. And there also emerged a class of liberal professionals: lawyers, physicians, notaries, journalists, printers and publishers, surveyors, and engineers.

Together these categories made up an emerging middle class that occupied a socioeconomic and cultural space between the old elites of the Loyalist Family Compacts, the military leadership, and the vice-regal governors on the one side, and the agrarian and working classes on the other. Shared values of the middle class included enthusiasm for literacy and schooling, moral advancement, the primacy of the individual as the key unit in society, the growth and spread of institutions, democratic principles, patriarchy, and the separation of public and private spheres.

In some ways, these values mimicked the upper class, but the middle class also believed in social mobility and the fluidity of social structures, a position that Tories detested. For the upper classes, everyone had a more-or-less fixed, assigned role to play in the social order. For the middle classes, education and (adult male) equality were the keys to advancement and a better society as a whole. As one historian writes of the middle class emerging in Halifax in the second quarter of the century, “growing in absolute numbers, increasingly literate, with ever more disposable income and leisure time, members of these strata tended to become, over time, increasingly self-conscious and ambitious.”[7]

One example was the Red River patriarch Alexander Ross, who started out as an amateur schoolmaster in Lower Canada, rising through the fur trade to become sheriff of Assiniboia. His son James attended university in Toronto and became a journalist, while another son, William, became a postmaster (a bureaucratic position that only came into existence with the invention of the organized postal system). A contemporary in Prince Edward Island, Edward Jarvis, trained as a lawyer in New Brunswick and London and ascended to the post of chief justice on the island colony. His sons Munson, Henry, and William were destined for careers in law, medicine, and the clergy, respectively.[8]

The British North American middle classes left a definite fingerprint on the mid-19th century. The houses they lived in displayed a scaled-down architecture from those of the elites: they were designed with the nuclear family in mind and included “transition zones” from the public space — the parlour — to the private spaces in the rest of the structure. As one study describes the situation, “Middle-class family life in the Victorian era was characterized by two related developments. The first is generally referred to as the ‘domesticization’ of the household, a clear separation of work-life and home-life and the withdrawal of the various household members into the privacy of the home, which became the central social unit for ‘the transmission of culture, the maintenance of social stability, and the pursuit of happiness.'”[9] The house gave form to the lives of its inhabitants and was both the academy and the factory floor on which girls learned domestic skills. The role of hostess was held by the matriarch until age and/or health compromised her ability to be the public face of the family in the private space of the home. The eldest daughter would then typically step into that position, thus playing a role in the oversight of household accounts, any servants the household might employ (e.g., cooks, nannies, governesses), and entertaining guests. The scale of these duties should not be minimized as they were often physically demanding and usually unceasing. Many young Canadian women could not escape these roles and faced spinsterhood rather than abandon the responsibilities of the patriarch’s hearth and home.

Key Points

- Old social classes survived into Victorian British North America while entirely new social categories appeared.

- Differences in social class became more widely felt, especially with the middle class and the upper class.

- Sectarian loyalties and rivalries marked life across British North America as did growing anti-clericalism.

- The growing trend toward proletarianization increasingly challenged the position of artisans and craftsmen/women.

- A middle class with common features emerged, and it was increasingly critical of the power appropriated by the well-off merchant classes and Loyalist elites.

Attributions

Figure 10.E1

Canadian Man and Woman in their Winter Dress by Victuallers is in the public domain.

Figure 10.E2

A French Canadian Lady in her Winter Dress and a Roman Catholic Priest by Metilsteiner is in the public domain.

Figure 10.E3

Habitans in their Summer Dress by Metilsteiner is in the public domain.

Figure 10.E4

Canadian Habitants by Jeangagnon is in the public domain.

Figure 10.E5

Canadian Habitant in Winter by P199 is in the public domain.

Figure 10.8

Ravenscrag by Jbarta is in the public domain.

Figure 10.9

Charlotte Trottier Desrivieres by shootmathers is used under a CC-BY-SA 2.5 license.

- Frederick H. Armstrong and Ronald J. Stagg, “MACKENZIE, WILLIAM LYON,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 9 (University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003). Accessed October 9, 2014, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mackenzie_william_lyon_9E.html . ↵

- Edward Macdonald, "Who's Afraid of the Fenians? The Fenian Scare on Prince Edward Island, 1865-1867," Acadiensis 38, no.1 (Winter/Spring 2009). ↵

- Allen B. Robertson, “BARRY, ROBERT,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 7 (University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003). Accessed January 15, 2015, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/barry_robert_7E.html . ↵

- Kenneth Norrie and Douglas Owram, A History of the Canadian Economy (Toronto: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1991), 234. ↵

- Gregory Kealey, "Artisans Respond to Industrialization: Shoemakers, Shoe Factories and the Knights of St. Crispin in Toronto," in Age of Transition: Readings in Canadian Social History, ed. Norman Knowles (Toronto: Harcourt Brace, 1998), 161-4. ↵

- Robert McIntosh, "Sweated Labour: Female Needleworkers in Industrializing Canada," in Age of Transition: Readings in Canadian Social History, ed. Norman Knowles (Toronto: Harcourt Brace, 1998), 178-80. ↵

- David A. Sutherland, "Voluntary Societies and the Process of Middle-Class Formation in Early-Victorian Halifax, Nova Scotia," Journal of the Canadian Historical Association 5 (1994): 239. ↵

- J.M.Bumsted and Wendy Owen, "The Victorian Family in Canada in Historical Perspective: The Ross Family of Red River and the Jarvis Family of Prince Edward Island," Manitoba History 13 (Spring 1987): 12-18. ↵

- Ibid., 15. ↵