10.10 Leisure and Recreation

One social historian, Bonnie Huskins, has shown how public feasts became opportunities to link the middle-class element with a larger world while, at the same time, instructing citizens in the rules of good behaviour. After the French Revolution and the dispersal to other capitals of Parisian chefs, cuisine became a novel matter. The upper classes promoted its diffusion but it was really the middle classes, with their dense networks between cities in North America and Europe, who were best positioned to adopt and promote the styles associated with high-style feasting. Multi-course meals, the paring of wines with meats and fish, and even the banqueting halls themselves — not to mention the embryonic beginnings of something truly new, the restaurant — were standard features, and they were reproduced faithfully from one city to the next. A banquet of community leaders in Saint John was purposely as similar to one in Toronto or Bristol as possible so as to demonstrate a belonging to the Victorian bourgeoisie.[1] Conformity was a good thing.

The notion of leisure time took on new meaning in the 19th century. “Old money” — the wealth that used to be the monopoly of the very powerful — always enjoyed leisure, but the people of the cities and towns and farms expected very little leisure time. The middle classes experienced increased leisure first, as they found themselves in a position to hire others to do tasks that freed them up to indulge in interests outside of work.

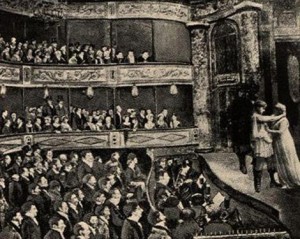

A Night at the Opera

Middle-class British North America was, in some regards, an extension of new middle-class values spiralling outward from Europe from the late 18th century on. One can chart, for example, the spread of opera houses around the Atlantic rim in these years as an indicator of how high culture or high style was emerging from palaces and manor houses and into public facilities (usually operated with a profit in mind). Theatres and music halls are further examples of this expression of bourgeois values.

These venues provided opportunities to people to show off their disposable wealth and the availability of leisure time; they were also a way to promote civic and cultural values. Halifax’s two Grand Theatres first appeared in the 1780s and were known for their productions of West End farces from London, only tending toward more serious stuff 50 years later. In 1825 a grocer and a merchant in Montreal convinced John Molson to join them in building the city’s first theatre, the Theatre Royal, where Shakespearean drama predominated.[2]

Similarly, public museums began to appear. Abraham Gesner (a physician, geologist, New Brunswick’s first provincial geologist, and the inventor of kerosene) established the Museum of Natural History, now the New Brunswick Museum, in Saint John in 1842. It was, significantly, part of the Mechanics’ Institute building, a landmark in most British North American towns of any size, one dedicated to the educational uplift of skilled working men.[3]

A Day at the Races

Working class or proletarian tastes were different. While the middle and upper classes frequented classical theatres and parlour performances of music, those who were poorer were drawn to circuses, competitions featuring feats of strength, and races between humans, animals, and boats. Gambling was widespread and gained popularity through the century both as a kind of skill but also as a means of improving one’s financial situation in an instant. Rural people in particular competed with and through their livestock and pets for reputation and money: everything from horse races to cockfights, dogfights, and bear-baiting endured in the countryside and even in some lower-class urban saloons.

Two features united these working-class leisure activities and the historical processes working on them. First, they were principally about individual skills, abilities, or fortune. They were not team sports, which was a style of recreation that was introduced with vigour in the 1870s and 1880s by middle-class reformers disturbed by working-class and agrarian pastimes. Second, industrial capitalism reduced the time available for leisure activities from 1818 on. The post-Confederation battle to reduce the length of the work day in industrial settings — the nine-hour day movement — arose because employers in the early decades of the century felt entitled to keep people at work for as much as 14 hours a day for six days a week. Leisure time, in this context, was often regarded by employers and the middle classes as subversive. Its visibility receded to the physical margins of towns and cities, out of sight and out of mind. When it reappeared in town settings, it became heavily critiqued and policed and in some instances banned.[4] This was nowhere more clear than in the regulation of drinking and gambling.

Public houses, or pubs, were an important part of town life from the 18th century but as evangelical Christianity gained more strength, drinking establishments fell afoul of emerging ideas of respectability. From the mid-19th century, pubs became increasingly a working-class or plebeian phenomenon. They also had an important role to play for travellers as these were among the first hotels in British North America. The “Mile Houses” of the Cariboo Wagon Road in British Columbia that ran from the Fraser Canyon to the goldfields were hotels and “watering holes,” as were the great many inns along the main roads of the older colonies.

The battle against drink itself became an important leisure time activity in the 19th century. Temperance movements appeared throughout British North American but rose first in the Maritimes. Amherst, Nova Scotia, contends for the title of cradle of temperance, because its Baptist congregation took up the cause as early as 1829. The appeal of temperance resided in the opportunities it presented for civic engagement by people often on the margin (like members of minority sects), a chance to criticize the moral laxity of the snobbish wealthy (who were both hefty consumers and commercial producers of liquor), and an opening for Christian proselytizing of the poor, Aboriginal peoples, and working men and women.

The popularity of drinking in some communities could be explained in its own right by the appalling state of water supplies. As suspicion of foul water as a source of disease spread so did preference for beer and liquors. Temperance was also a kind of self-policing in the absence of anything like a police force. If drinking lay behind domestic and public violence, vandalism, and disorder, and if there was no one to round up the drunks, then persuading people to give up drink seemed like a good strategy.[5]

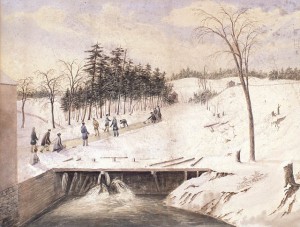

The Sporting Life

Organized sports was another expression of leisure in the 19th century, although most of the organized sports familiar to us now appeared after Confederation. The wilderness sports (canoeing, snowshoeing), the more bucolic sports (curling, horse racing), and some inherited British sports (cricket, some of the Highland sports), and one sport readily associated with Aboriginal people (lacrosse) dominated. Wrestling and other forms of hand-to-hand battle were also popular. Logging camps, of course, begat logging competitions. Any structured, spectator-oriented event was typically also a drinking and gambling event. If a fight or foot race was staged, it would draw a crowd for miles and a substantial purse, perhaps as much as a week’s wages. Less-structured pastimes included fishing and hunting, recreational activities that doubled as a source of food and perhaps income. In colonial society women were discouraged from participating in many of these activities; mid-century organized sports in particular were male-only propositions. Women’s presence as spectators at competitions was criticized by middle-class reformers who regarded the ubiquity of gambling as corrosive to morality generally.

Class and ethnic divisions were also apparent. For example, the Montreal Curling Club was established in 1807 by and for the local Scots, and membership fees and vetting ensured the club remained exclusive. Efforts were made, as well, to make organized tournaments like horse racing a private and better-class affair but, as one historian notes wryly, “attempts to enclose race courses had only mixed results since the working class was as capable of climbing as it was of drinking.”[6] Racial as well as class boundaries were patrolled by the organizers of sporting and recreational events. Afro-British North Americans faced a “colour line” in a variety of sports: in 1835 a Niagara horse racing club specified that “no Black shall be permitted to ride on any pretext whatsoever.” Historian Frank Cosentino points out that there are different ways of reading that prohibition as it could have arisen from a broad racist prejudice, or it could have been aimed at one particularly good rider; likewise it might have stemmed from a class prejudice, as all African-Canadian riders would have been drawn from a working or servant (or even former slave) class and would therefore have been unwelcome in a race made up of “gentlemen” and their grooms. Attempts to bar William Berry (a.k.a. Bob, Black Bob, “the coloured giant”) from rowing competitions in 1860s Toronto seems to have stemmed more from his social class (which, of course, was informed by race) than by his skin pigment.[7]

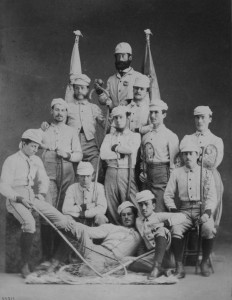

There were other instances in which sport worked as an expression of racial and imperial values. The development of lacrosse in mid-century is an example. The modern game was appropriated from Aboriginal traditions by the non-Aboriginal community and modified significantly. The Montreal Olympic Club — a gentlemen’s recreational association — began promoting the newly structured game in 1844. The Montreal Lacrosse Club was established in 1856 and produced the first set of written rules of the game a decade later. These all-White, all-male, all-gentlemen’s clubs and teams would, from time to time, play against Iroquois teams from Kahnawake and Akwasasne — and typically lose. However, Victorian society took poorly to the idea of White gentlemen failing to overcome Aboriginal teams, so the results were sometimes fiddled to the disadvantage of the more skilled Aboriginal sides.[8]

Recreational Travel

Tourism as a popular recreational activity developed in the 1820s, principally at Niagara Falls. The early canals and railways made it possible for large numbers of people to make their way to either the American or the Canadian side of the Falls. Beginning in the 1820s, daredevils made an appearance and by the 1830s whole ships were sent over the edge of the falls and smashed to pieces on the rocks below to entertain large crowds. In some instances animals — some local and domestic, others exotic — crammed these doomed vessels, a feature that somehow made the spectacle more exciting.

Social Life

The rise of cities and towns made it possible for people to come together behind common causes and interests. In the larger cities, men mimicked their British and American counterparts by establishing gentlemen’s clubs, which were usually housed in elegant buildings near the centre of the business district. Membership was exclusive and selective. The Beaver Club in Montreal was the gathering place of leading figures in the post-Conquest fur trade who wanted to socialize, dine, and conduct business. The Toronto Club was established 50 years later, in 1837, as the commercial capital of Upper Canada began to consolidate its power, and the Halifax Club was established in 1862 in a grand building a block from the waterfront.

If gentlemen’s clubs were bastions of patriarchal upper-class maleness, other voluntary associations were far less so. The first half of the century saw the spread of Mechanics’ Institutes: centres for adult literacy education, debate, and access to reading materials. Many of these subsequently became British North America’s earliest public libraries. They were established in the major centres of the eastern colonies, and they even appeared across British Columbia in the 1860s. Generally the objective of the Mechanics’ Institutes was to “ensure that men’s leisure hours were spent in sober self-improvement rather than ‘the morbid attractions of billiard tables, and saloons.'”[9] In some communities, Halifax for example, the Mechanics’ Institute “welcomed anyone, male or female, who could pay an annual membership fee of 10 [shillings].”[10]

Other voluntary associations vied for popularity. Freemasonry (a.k.a. the Masonic Lodge) had deep roots in North America and attracted, by the early 19th century, a constituency that was more professional than skilled labour. Other similarly semi-secret benevolent societies also gained ground: the Oddfellows and Foresters grew in popularity from mid-century. According to one source, “more than one-third of the Orange Lodges that existed in the nineteenth century were established during the 1850s, when approximately 550 were formed.”[11] Given the population of British North America at the time, it is likely that there wasn’t a town with more than 1,000 people in it that didn’t include an Orange Lodge and other societies as well.

Part of the popularity of these organizations lay in the rapid rate of urban growth at mid-century: so many people were newcomers and strangers that voluntary associations offered a ready-made community. They also offered links across the country. When George Walkem (1834-1908), a future premier of British Columbia, first arrived from the east in Kamloops, he walked straight from the train station to the Masonic Lodge. There he found connections who could help him find lodgings and work. Walkem wasn’t the only Mason who would parlay his association life into political success. Alexander Keith (1795-1873), the Nova Scotian brewer, rose to the rank of Grand Master of Halifax Freemasonry, a position that put him at the head of parades, in front of crowds, and made him a spokesman for his brethren in the temple.[12] Even if the Masons did not conspire to promote Keith politically, his connections across the whole of middle-class Halifax via the Lodge put him in a good position: only property owners could vote and that constituency was the same as the Masons.

A further advantage of being attached to a social group was financial: many of the benevolent societies maintained cooperative insurance funds that covered the cost of funerals, widows’ pensions, and the like. Of course one key attraction was simply the opportunity to socialize with other men in a convivial environment.

Most of these associations were open to men only. Their position on the spectrum of class awareness is more complex. Some nurtured — intentionally or otherwise — a growing consciousness among workers that their interests were not always aligned with those of their employers. The men’s groups were also critical in the development of a sense of respectability as part of a civic-minded men’s organization, a trend that impacted mid- and late-19th century ideals of masculinity. Most were self-consciously Christian and, at the same time, mostly anti-clerical. The Masons were, for this reason, a target of the Lower Canadian Catholic clergy’s criticisms through the 19th century. The Orange Lodge, of course, was based on a strident anti-Catholicism that was the enmity of the Catholic clergy. Some of the values of these organizations eventually migrated to the embryonic labour associations of the era.

Artisans had long organized in guilds, some of which dated back to the Middle Ages, and these served as social supports as well. The tradition of the guild travelled to the European settlements across the Americas, but faced challenges in the 19th century with the beginnings of industrialization. Nevertheless, some guilds enjoyed boom times. Urban population and commercial growth fed the construction trades, especially carpenters whose services were in such high demand that planing and moulding mills sprang up to prefabricate some of what carpenters had been doing by hand.

As cities grew more densely packed, moreover, the risk of fire expanded. This was addressed by civic ordinances calling for more stone and brick construction. Effectively, the carpenters’ success was their undoing, but stonemasons and bricklayers saw their numbers increase dramatically. In Halifax, for example, the number of carpenters quadrupled from a little over a hundred in 1838 to 408 in 1861; in the same years, the number of stonemasons grew from 50 to 223.[13] Organizations that advocated for the stonemasons kept pace.

Women’s associations tell a somewhat different story. In the absence of professional and public roles for women in the early 19th century cities and towns, there was little demand for associations that promoted and nurtured women’s enterprise. Women’s public engagement in voluntary associations was, therefore, frequently aligned with community and self-betterment and generally in a Protestant context. The temperance movement, already mentioned, provided an important early outlet for middle-class women’s public spirit. In 1844, Halifax was home to a Female Temperance and Benevolent Society. Organizations like this one were pivotal in developing a civic sensibility.

Just as the men’s associations welded mutual interest and urban respectability, the women’s organizations (small though they were in number) were an opportunity to promote women’s roles as nurturers within a patriarchal context and to do so within the relatively new context of city dwelling. These early female associations would bloom into more politically focused movements after Confederation.

Key Points

- The wealth of the merchant elite and the urban middle-classes supported the creation of cultural institutions like theatres and museums.

- Plebian recreations like drinking and gambling fit within the context of limited leisure time and attracted criticism from other social classes.

- Associations and clubs were important agencies of social welfare, sites of networking, and instruments of political engagement.

Attributions

Figure 10.12

Theatre Royal Montreal 1825 by Jeangagnon is in the public domain.

Figure 10.13

Curling on the Don River by Skeezix1000 is in the public domain.

Figure 10.14

Montreal Lacrosse Club 1867 by Jeangagnon is in the public domain.

- Bonnie Huskins, "From Haute Cuisine to Ox Roasts: Public Feasting and the Negotiation of Class in Mid-19th-Century Saint John and Halifax," Labour/Le Travail 37 (Spring 1997): 9-36. ↵

- Owen Klein, "The Opening of Montreal's Theatre Royal, 1825," Theatre Research in Canada/Recherches Théâtrales au Canada I, issue 1 (Spring 1980). http://journals.hil.unb.ca/index.php/tric/article/view/7539/8598 ↵

- New Brunswick Museum, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/New_Brunswick_Museum ↵

- Alan Metcalfe, "Leisure, Sport and Working-Class Culture: Some Insights from Montreal and the Northeast Coalfields of England," in Leisure, Sport and Working Class Cultures: Theory and History (Toronto: Garamond Press, 1988), 70-1. ↵

- C. Mark Davis, "Small Town Reformism: The Temperance Issue in Amherst, Nova Scotia," in People and Place: Studies of Small Town Life in the Maritimes, ed. Larry McCann (Sackville: Acadiensis Press, 1987), 125-8. ↵

- Frank Cosentino, Afros, Aboriginals and Amateur Sport in Pre World War One Canada (Ottawa: Canadian Historical Association Booklet no.26, 1998), 3-4. ↵

- Ibid., 6-7. ↵

- Ibid., 15. ↵

- Adele Perry, On the Edge of Empire: Gender, Race, and the Making of British Columbia (Toronto: UTP, 2001), 64. ↵

- David A. Sutherland, "Voluntary Societies and the Process of Middle-Class Formation in Early-Victorian Halifax, Nova Scotia," Journal of the Canadian Historical Association 5 (1994): 241-2. ↵

- Bryan D. Palmer, Working-Class Experience: Rethinking the History of Canadian Labour, 1800-1991, 2nd edition (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1992), 95-7. ↵

- David A. Sutherland, "Voluntary Societies and the Process of Middle-Class Formation in Early-Victorian Halifax, Nova Scotia," Journal of the Canadian Historical Association 5 (1994): 245. ↵

- Susan Buggey, "Building Halifax, 1841-1871," Acadiensis X, issue 1 (Autumn 1980): 102-3. ↵