10.3 Immigration

From 1783 until 1812 the most important source of immigrants to British North America was the United States. Movement across the border was easy and the host community was, outside of Lower Canada, overwhelmingly and increasingly North American in its accents and values. That ended with the War of 1812. After 1815 British North America became much more British than it had ever been before.

Emigration from the British Isles was the single greatest source of settlers in the Atlantic colonies, a fact that distinguishes their society from that of the Canadas in these years. Scottish settlers under the guidance of Lord Selkirk descended upon Prince Edward Island to take up farms in the early days of the century, and they were followed in the years to come by many others. Mostly these were Highland Scots, removed from their ancestral farmlands by the process known as the “clearances.” They were followed by Irish immigrants who came to represent a significant share of colonial population by 1850.

Irish Immigrants

Ireland produced the largest waves of emigration of any European country during the 19th century. This phenomenon is often associated exclusively with the Famine Irish, the millions of refugees from the potato famine that wracked their homeland in the late 1840s. Irish migration to British North America, however, began in earnest much earlier. In the dying days of the Napoleonic Wars, Irish immigrants began arriving in east coast ports in large numbers. The towns of Newcastle, Chatham, and Miramichi saw hundreds arrive before 1820. Not all were Catholics but almost all were economically on the margin. Sectarian hostility between the Irish Protestants and Catholics who arrived around the same time soon spread to the larger host population.

Further Irish immigration tended to be badly timed, and the reception of the host communities was predictably muted at best, hostile at worst. The post-Napoleonic War years witnessed economic downturns in many parts of the British Isles, including Ireland. In the 1820s, as the farming frontier was growing in Upper Canada and in Lower Canada’s Eastern Townships, Irish immigrants arrived. Some of these had enough money to make a go of it. They were followed in the 1830s, however, by less prosperous countrymen and women who were fleeing more severe hardship at home. Overwhelmingly Catholic, they arrived in large numbers in the St. Lawrence, and the mortality among passengers was severe.

In June 1832, Irish immigrants brought with them a hidden passenger onboard the Carrick: cholera. Having killed tens of thousands in Britain, the disease came ashore at Quebec City and spread rapidly to Montreal and then Upper Canada. More than 9,000 Canadians — Upper and Lower — died, the largest concentration being in Montreal.

Cholera is associated with human waste, and at the time, sewers in the towns were very poorly developed; it was common practice to dump buckets of sewage into the streets where it mixed with an abundant supply of horse manure. The Irish — poor and almost immediately shunned by the locals — found themselves in shantytowns with even worse drainage or in quarantine facilities (specifically on Grosse Isle) where sanitation was appalling. As a result, the Irish immigrants themselves died in huge numbers. (This was a near-global epidemic, one that originated in India and by 1835 had made landfall on the northwest coast. There, cholera joined measles, mumps, and other exotic diseases that easily claimed 25% to 35% of the Aboriginal communities they infected.)[1]

Another consequence of the cholera epidemic was social and political turmoil, which was especially acute in Lower Canada where fear of a British plot to eradicate the Catholic Canadien population survived from generation to generation. Were the Irish merely instruments of British contempt for the Canadiens? Many thought so at the time. The Irish were, therefore, ostracized and discriminated against while the clergy and other spokesmen for the Canadiens whipped up feeling against the British generally. The cholera epidemic was, then, one factor among several in the 1830s that led to growing support for a rebellion.

Irish immigration in the 1840s must be placed in this context. Fear of cholera and diseased immigrants was a reality. As well, the Irish Canadians had moved into fields of work such as canal construction, which were generally regarded dimly by most English and French Canadians, and this increased the anti-Irish sentiment. The independent farmer was the antithesis of the low-wage-earning, work-camp-dwelling proletarian. “Townies” viewed the Irish navvies as rough and uncivilized and a danger to their safety. Worse still, the land boom in Upper Canada that had sustained the economy alongside the wheat boom was in a trough in the late 1840s. Immigration had been much sought after when there was a lot of land available and when it fetched a good price; when the Famine Irish arrived they were too poor to buy land, the market was depressed anyway, and no one was enthusiastic about more competition. Things, of course, were much worse for the Irish themselves. Those who were quarantined on Grosse Isle and on Partridge Island in the Bay of Fundy in 1847 had to further contend with an outbreak of typhus. Thousands died.

Even in Upper Canada voices could be heard criticizing the British government for shovelling out its poor into British North America. Immigration from Ireland transformed Toronto from an essentially anglophone and Protestant city to one of pluralities: by 1860 there were comparable numbers of Catholics and Anglicans, followed by smaller numbers of Presbyterians, Methodists, and still smaller denominations.[2] Almost all of these Catholics were Irish. Their presence gave purpose to the Orange Order, whose lodges stood as expressions of Protestant authority and xenophobic reaction to the immigrant masses. This arose, in large part, because the Irish tended to settle in urban areas, though not necessarily in tight ethnic enclaves. In Montreal they dominated St. Anne’s Ward, but in Toronto they were spread throughout the east and west ends, wherever affordable housing could be found.[3]

Key Points

- The British Isles contributed the largest number of immigrants to British North America between 1818 and 1867, the Irish constituting a major share.

- Many of the 19th century immigrants were refugees from landlessness, and poverty, and/or famine.

- Conditions for immigrants were typically poor and worsened by the presence of epidemic diseases.

- The Irish, Scots, Welsh, and English immigrants of these years contributed to the diversification of cultural institutions as well as sectarian hostilities.

Attributions

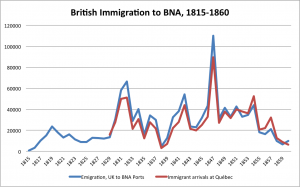

Figure 10.2

British Immigration to BNA, 1815-1860, by John Belshaw is used under a CC-BY 4.0 license.

Figure 10.3

View of Montreal 1852 by Skeezix1000 is in the public domain.

Long Descriptions

| Year | Emmigration, UK to BNA Ports | Immigrant arrivals at Quebec |

|---|---|---|

| 1815 | 0 | |

| 1817 | 10,000 | |

| 1819 | 22,000 | |

| 1821 | 10,000 | |

| 1823 | 11,000 | |

| 1825 | 10,000 | |

| 1827 | 16,000 | |

| 1829 | 17,000 | 18,000 |

| 1831 | 40,000 | 40,000 |

| 1833 | 45,000 | 45,000 |

| 1835 | 16,000 | 16,000 |

| 1837 | 30,000 | 21,000 |

| 1839 | 2,000 | 2,000 |

| 1841 | 39,000 | 24,000 |

| 1843 | 21,000 | 20,000 |

| 1845 | 30,000 | 21,000 |

| 1847 | 110,000 | 90,000 |

| 1849 | 23,000 | 23,000 |

| 1851 | 26,000 | 26,000 |

| 1853 | 32,000 | 37,000 |

| 1855 | 57,000 | 42,000 |

| 1857 | 21,000 | 18,000 |

| 1859 | 7,000 | 7,000 |

- Geoffrey Bilson, A Darkened House: Cholera in Nineteenth Century Canada (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1980). ↵

- Peter G. Goheen, "Currents of Change in a Canadian City, 1850-1900," in The Canadian City: Essays in Urban and Social History, eds. Gilbert A. Stelter and Alan F. J. Artibise (Ottawa: Carleton University Press, 1984), 93-4. ↵

- John Zucchi, A History of Ethnic Enclaves in Canada (Ottawa: Canadian Historical Association Booklet no.31, 2007), 3. ↵