ELM Review

Learning Objectives

- Review the conditions under which attitudes are best changed using spontaneous versus thoughtful strategies.

An In-Depth Review of the Elaboration Likelihood Model (ELM)

Neither social psychologists nor advertisers are so naïve as to think that simply presenting a strong message is sufficient. No matter how good the message is, it will not be effective unless people pay attention to it, understand it, accept it, and incorporate it into their self-concept. This is why we attempt to choose good communicators to present our ads in the first place, and why we tailor our communications to get people to process them the way we want them to.

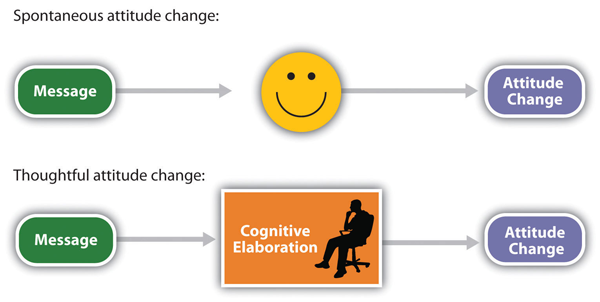

The messages that we deliver may be processed either spontaneously (other terms for this include peripherally or heuristically—Chen & Chaiken, 1999; Petty & Wegener, 1999) or thoughtfully (other terms for this include centrally or systematically). Spontaneous processing is direct, quick, and often involves affective responses to the message. Thoughtful processing, on the other hand, is more controlled and involves a more careful cognitive elaboration of the meaning of the message (Figure 4.6). The route that we take when we process a communication is important in determining whether or not a particular message changes attitudes.

Spontaneous Message Processing

Because we are bombarded with so many persuasive messages—and because we do not have the time, resources, or interest to process every message fully—we frequently process messages spontaneously. In these cases, if we are influenced by the communication at all, it is likely that it is the relatively unimportant characteristics of the advertisement, such as the likeability or attractiveness of the communicator or the music playing in the ad, that will influence us.

If we find the communicator cute, if the music in the ad puts us in a good mood, or if it appears that other people around us like the ad, then we may simply accept the message without thinking about it very much (Giner-Sorolla & Chaiken, 1997). In these cases, we engage in spontaneous message processing, in which we accept a persuasion attempt because we focus on whatever is most obvious or enjoyable, without much attention to the message itself. Shelley Chaiken (1980) found that students who were not highly involved in a topic because it did not affect them personally, were more persuaded by a likeable communicator than by an unlikeable one, regardless of whether the communicator presented a good argument for the topic or a poor one. On the other hand, students who were more involved in the decision were more persuaded by the better message than by the poorer one, regardless of whether the communicator was likeable or not—they were not fooled by the likeability of the communicator.

You might be able to think of some advertisements that are likely to be successful because they create spontaneous processing of the message by basing their persuasive attempts around creating emotional responses in the listeners. In these cases, the advertisers use associational learning to associate the positive features of the ad with the product. Television commercials are often humorous, and automobile ads frequently feature beautiful people having fun driving beautiful cars. The slogans “I’m lovin’ it,” “Life tastes good,” and “Good to the last drop” are good ads in part because they successfully create positive affect in the listener.

In some cases emotional ads may be effective because they lead us to watch or listen to the ad rather than simply change the channel or do something else. The clever and funny TV ads that are broadcast during the Super Bowl every year are likely to be effective because we watch them, remember them, and talk about them with others. In this case, the positive affect makes the ads more salient, causing them to grab our attention. But emotional ads also take advantage of the role of affect in information processing. We tend to like things more when we are in a good mood, and—because positive affect indicates that things are okay—we process information less carefully when we are in a good mood. Thus the spontaneous approach to persuasion is particularly effective when people are happy (Sinclair, Mark, & Clore, 1994), and advertisers try to take advantage of this fact.

Another type of ad that is based on emotional response is one that uses fear appeals, such as ads that show pictures of deadly automobile accidents to encourage seatbelt use or images of lung cancer surgery to decrease smoking. By and large, fearful messages are persuasive (Das, de Wit, & Stroebe, 2003; Perloff, 2003; Witte & Allen, 2000). Again, this is due in part to the fact that the emotional aspects of the ads make them salient and lead us to attend to and remember them. And fearful ads may also be framed in a way that leads us to focus on the salient negative outcomes that have occurred for one particular individual. When we see an image of a person who is jailed for drug use, we may be able to empathize with that person and imagine how we would feel if it happened to us. Thus this ad may be more effective than more “statistical” ads stating the base rates of the number of people who are jailed for drug use every year.

Fearful ads also focus on self-concern, and advertisements that are framed in a way that suggests that a behavior will harm the self are more effective than those framed more positively. Banks, Salovey, Greener, and Rothman (1995) found that a message that emphasized the negative aspects of not getting a breast cancer screening mammogram (e.g., “Not getting a mammogram can cost you your life”) was more effective than a similar message that emphasized the positive aspects of having a mammogram (e.g., “Getting a mammogram can save your life”) in convincing women to have a mammogram over the next year. These findings are consistent with the general idea that the brain responds more strongly to negative affect than it does to positive affect (Ito, Larsen, Smith, & Cacioppo, 1998).

Although laboratory studies generally find that fearful messages are effective in persuasion, they may be less useful in real-world advertising campaigns (Hastings, Stead, & Webb, 2004). Fearful messages may create a lot of anxiety and therefore turn people off to the message (Shehryar & Hunt, 2005). For instance, people who know that smoking cigarettes is dangerous but who cannot seem to quit may experience particular anxiety about their smoking behaviors. Fear messages are more effective when people feel that they know how to rectify the problem, have the ability to actually do so, and take responsibility for the change. Without some feelings of self-efficacy, people do not know how to respond to the fear (Aspinwall, Kemeny, Taylor, & Schneider, 1991). Thus if you want to scare people into changing their behavior, it may be helpful if you also give them some ideas about how to do so, so that they feel like they have the ability to take action to make the changes (Passyn & Sujan, 2006).

Thoughtful Message Processing

When we process messages only spontaneously, our feelings are more likely to be important, but when we process messages thoughtfully, cognition prevails. When we care about the topic, find it relevant, and have plenty of time to think about the communication, we are likely to process the message more deliberatively, carefully, and thoughtfully (Petty & Briñol, 2008). In this case we elaborate on the communication by considering the pros and cons of the message and questioning the validity of the communicator and the message. Thoughtful message processing occurs when we think about how the message relates to our own beliefs and goals and involves our careful consideration of whether the persuasion attempt is valid or invalid.

When an advertiser presents a message that he or she hopes will be processed thoughtfully, the goal is to create positive cognitions about the attitude object in the listener. The communicator mentions positive features and characteristics of the product and at the same time attempts to downplay the negative characteristics. When people are asked to list their thoughts about a product while they are listening to, or right after they hear, a message, those who list more positive thoughts also express more positive attitudes toward the product than do those who list more negative thoughts (Petty & Briñol, 2008). Because the thoughtful processing of the message bolsters the attitude, thoughtful processing helps us develop strong attitudes, which are therefore resistant to counterpersuasion (Petty, Cacioppo, & Goldman, 1981).

Which Route Do We Take: Thoughtful or Spontaneous?

Both thoughtful and spontaneous messages can be effective, but it is important to know which is likely to be better in which situation and for which people. When we can motivate people to process our message carefully and thoughtfully, then we are going to be able to present our strong and persuasive arguments with the expectation that our audience will attend to them. If we can get the listener to process these strong arguments thoughtfully, then the attitude change will likely be strong and long lasting. On the other hand, when we expect our listeners to process only spontaneously—for instance, if they don’t care too much about our message or if they are busy doing other things—then we do not need to worry so much about the content of the message itself; even a weak (but interesting) message can be effective in this case. Successful advertisers tailor their messages to fit the expected characteristics of their audiences.

In addition to being motivated to process the message, we must also have the ability to do so. If the message is too complex to understand, we may rely on spontaneous cues, such as the perceived trustworthiness or expertise of the communicator (Hafer, Reynolds, & Obertynski, 1996), and ignore the content of the message. When experts are used to attempt to persuade people—for instance, in complex jury trials—the messages that these experts give may be very difficult to understand. In these cases, the jury members may rely on the perceived expertise of the communicator rather than his or her message, being persuaded in a relatively spontaneous way. In other cases, we may not be able to process the information thoughtfully because we are distracted or tired—in these cases even weak messages can be effective, again because we process them spontaneously (Petty, Wells & Brock, 1976).

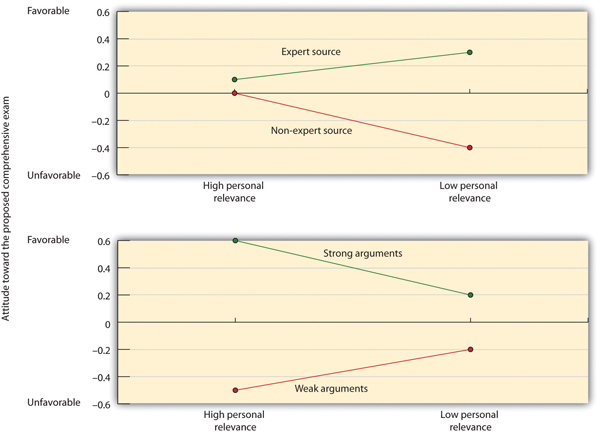

Petty, Cacioppo, and Goldman (1981) showed how different motivations may lead to either spontaneous or thoughtful processing. In their research, college students heard a message suggesting that the administration at their college was proposing to institute a new comprehensive exam that all students would need to pass in order to graduate, and then rated the degree to which they were favorable toward the idea. The researchers manipulated three independent variables:

- Message strength. The message contained either strong arguments (persuasive data and statistics about the positive effects of the exams at other universities) or weak arguments (relying only on individual quotations and personal opinions).

- Source expertise. The message was supposedly prepared either by an expert source (the Carnegie Commission on Higher Education, which was chaired by a professor of education at Princeton University) or by a nonexpert source (a class at a local high school).

- Personal relevance. The students were told either that the new exam would begin before they graduated (high personal relevance) or that it would not begin until after they had already graduated (low personal relevance).

As you can see in Figure 4.8, Petty and his colleagues found two interaction effects. The top panel of the figure shows that the students in the high personal relevance condition (left side) were not particularly influenced by the expertise of the source, whereas the students in the low personal relevance condition (right side) were. On the other hand, as you can see in the bottom panel, the students who were in the high personal relevance condition (left side) were strongly influenced by the quality of the argument, but the low personal involvement students (right side) were not.

These findings fit with the idea that when the issue was important, the students engaged in thoughtful processing of the message itself. When the message was largely irrelevant, they simply used the expertise of the source without bothering to think about the message.

Because both thoughtful and spontaneous approaches can be successful, advertising campaigns, such as those used by Apple, carefully make use of both spontaneous and thoughtful messages. For example, the ad may showcase the new and useful features of a device like the iPad amid scenes of happy, creative, or productive people and an inspiring soundtrack.