Communications Studies of Persuasion

Learning Objectives

- Understand findings from experiments using the Yale Attitude Change Approach

Aristotle’s three rhetorical appeals—ethos, logos, and pathos—have been employed as persuasive strategies for two thousand years even though there was no proof they were effective. It wasn’t until the 1940s that Psychologists began studying persuasion from a scientific perspective using social experiments and evidence to produce new theories. Although based in social science, such persuasive strategies are regularly employed and researched in communication due to their role in advertising, marketing, politics, and other industries.

Yale Attitude Change Approach

The topic of persuasion has been one of the most extensively researched areas in social psychology (Fiske et al., 2010). During the Second World War, Carl Hovland extensively researched persuasion for the U.S. Army. After the war, Hovland continued his exploration of persuasion at Yale University. Out of this work came a model called the Yale attitude change approach, which describes the conditions under which people tend to change their attitudes. Hovland demonstrated that certain features of the source of a persuasive message, the content of the message, and the characteristics of the audience will influence the persuasiveness of a message (Hovland, Janis, & Kelley, 1953). In other words, who (i.e. source) says what (i.e. content) to whom (i.e. audience)?

Source Features

Features of the source of the persuasive message include the credibility of the speaker (Hovland & Weiss, 1951) and the physical attractiveness of the speaker (Eagly & Chaiken, 1975; Petty, Wegener, & Fabrigar, 1997). Thus, speakers who are credible, or have expertise on the topic, and who are deemed as trustworthy are more persuasive than less credible speakers. Similarly, more attractive speakers are more persuasive than less attractive speakers. The use of famous actors and athletes to advertise products on television and in print relies on this principle. The immediate and long term impact of the persuasion also depends, however, on the credibility of the messenger (Kumkale & Albarracín, 2004).

Selecting Communicators

Following the approach used by some of the earliest social psychologists and that still forms the basis of thinking about the power of communication, we will consider which communicators can deliver the most effective messages to which types of message recipients (Hovland, Lumsdaine, & Sheffield (1949).

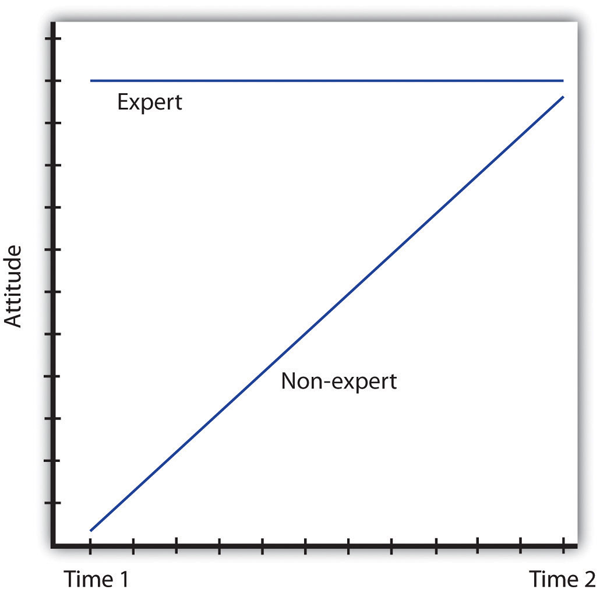

Although we are generally very aware of the potential that communicators may deliver messages that are inaccurate or designed to influence us, and we are able to discount messages that come from sources that we do not view as trustworthy, there is one interesting situation in which we may be fooled by communicators. This occurs when a message is presented by someone whom we perceive as untrustworthy. When we first hear that person’s communication, we appropriately discount it, and it therefore has little influence on our opinions. However, over time there is a tendency to remember the content of a communication to a greater extent than we remember the source of the communication. As a result, we may forget over time to discount the remembered message. This attitude change that occurs over time is known as the sleeper effect (Kumkale & Albarracín, 2004).

Perhaps you’ve experienced the sleeper effect. During high-profile election campaigns, candidates sometimes produce advertisements that attack their opponents. These kinds of communications occasionally stretch the truth in order to win public favor, which is why many people listen to them with a grain of salt. The trouble occurs, however, when people remember the claims made but forget the source of the communication. The sleeper effect is diagrammed in Figure 4.5, “The Sleeper Effect.”

Audience Features

Features of the audience that affect persuasion are attention (Albarracín & Wyer, 2001; Festinger & Maccoby, 1964), intelligence, self-esteem (Rhodes & Wood, 1992), and age (Krosnick & Alwin, 1989). In order to be persuaded, audience members must be paying attention. People with lower intelligence are more easily persuaded than people with higher intelligence; whereas people with moderate self-esteem are more easily persuaded than people with higher or lower self-esteem (Rhodes & Wood, 1992). Finally, younger adults aged 18–25 are more persuadable than older adults.

Message Features

Features of the message itself that affect persuasion include subtlety (the quality of being important, but not obvious) (Petty & Cacioppo, 1986; Walster & Festinger, 1962); sidedness (that is, having more than one side) (Crowley & Hoyer, 1994; Igou & Bless, 2003; Lumsdaine & Janis, 1953); timing (Haugtvedt & Wegener, 1994; Miller & Campbell, 1959), and whether both sides are presented. Messages that are more subtle are more persuasive than direct messages. Arguments that occur first, such as in a debate, are more influential if messages are given back-to-back. However, if there is a delay after the first message, and before the audience needs to make a decision, the last message presented will tend to be more persuasive (Miller & Campbell, 1959).

Key Takeaways

- Advertising is effective in changing attitudes, and principles of social psychology can help us understand when and how advertising works.

- Social psychologists study which communicators can deliver the most effective messages to which types of message recipients.

- Communicators are more effective when they help their recipients feel good about themselves. Attractive, similar, trustworthy, and expert communicators are examples of effective communicators.

- Attitude change that occurs over time, particularly when we no longer discount the impact of a low-credibility communicator, is known as the sleeper effect.