Chapter 3 – Area and Volume

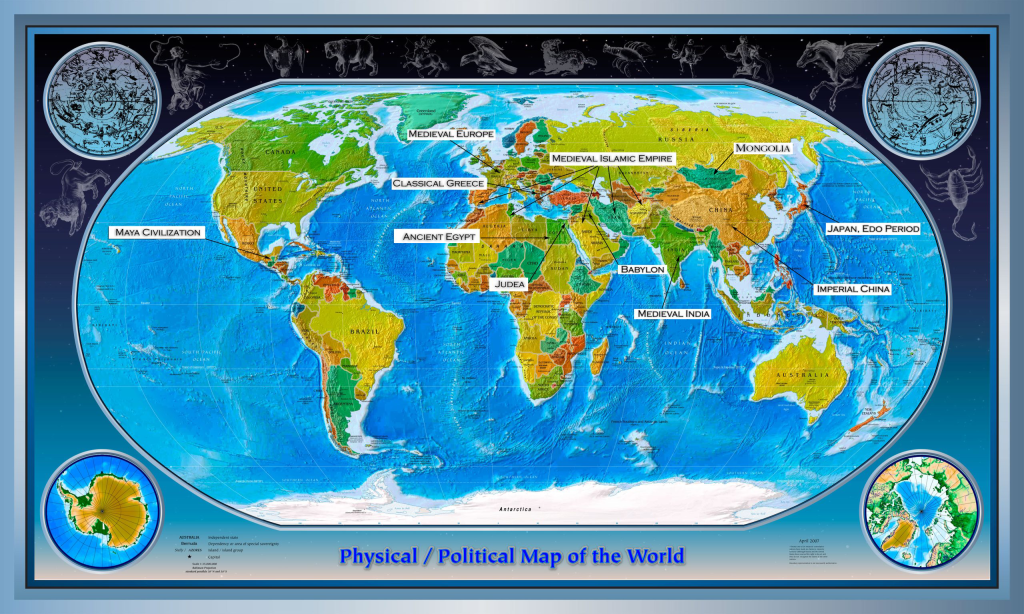

Map

1.1

1.19

Timeline

1.1

1.19

Introduction

On a scale of one to ten, how important do you think measurement is? Without realizing it, you just confirmed the importance of measurement. Imagine living in a world without it. How would you tell the time, keep score of a basketball game, or count your Instagram followers? In fact, the origin of mathematics can be traced back to two fundamental human activities: counting and measuring.

Measurement is how we subdivide and categorize the physical properties of our world into the meaningful symbols we communicate to each other. Without the ability to accurately measure time, size, distance, speed, direction, weight, volume, temperature, pressure, force, sound, light, or energy, to name a few, civilization as we know it would not be able to function!

One of the earliest forms of measurement is length. To this day, we still use an age-old unit of measurement for length: the foot. Have you ever wondered why a body part was used for measurement? The answer is that, before there were standardized units for measurement, the only objects available for measuring were those produced by nature itself! So, naturally, we used our own body parts to measure the world around us. Archaic as it may be, even the hand is still used to measure the height of horses!

Measurement units based on the human body were common to societies across the world. Take the fathom, for example. Still is used to estimate the depth of water, a fathom is equal to an average human male’s wingspan (the length between one’s outstretched arms), and has been used independently by societies in Asia, Northern Europe, and the Mediterranean. The Vikings called it “favn,” the Mongolians called it “ald,” the Greeks called it “orguia,” and the Russians called it “sazhen.” Can you estimate what hands, feet, and fathoms are in centimetres?

The problem with using human body parts as units of measurement, is that not everyone’s body is the same size. To address this issue, the rulers of ancient and medieval lands aimed to standardize measurements by using their own body parts. According to legend, the 12th century English king, Henry I, proclaimed that the yard would be the distance from the tip of his nose to the end of his outstretched thumb. The ancient Egyptian unit of measurement was the cubit – the length of the forearm from the elbow to the tip of the middle finger. But, they also had the royal cubit: a normal cubit plus the width of the palm of the current Pharaoh.

With all the confusion surrounding body parts as units of measurement, King John, of England, decreed in 1213 that there should be “one measure throughout our whole realm.” Hundreds of years later, we had successfully implemented a global unit of measurement independent of any body part: the metre.

Since the dawn of humanity, we have been on a quest to understand the universe we inhabit. This journey has given us mythology, religion, art, and many other cultural treasures. But, where they inspire and transcend, they fail at providing us a concrete and reliable picture of the material world. It is measurement that defines the world around us. As the bedrock of mathematics and science, our tools to create order out of chaos, human societies simply could not exist without it!

Egypt – Joseph and His Brothers

Unlike in mathematics, there is no all-encompassing formula to solve the problems that we face in life. Very often we find ourselves taking two steps forward and one step back. And, what’s more, we find that life is not a straight line, but an unpredictable zig-zag of events that, if we stay true to our values, ultimately lead us to our destination. In the biblical story of Joseph, we see just how perseverance through hardship can lead us to the light at the end of the tunnel.

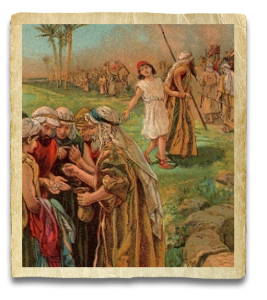

The story begins in ancient times in the land of Canaan which is now called Israel. At the age of seventeen, Joseph was given a colorful tunic from his father, Jacob, triggering the jealousy of Joseph’s brothers. To make matters worse, Joseph had a dream that predicted his brothers would one day bow to him. The idea of being inferior to the youngest-born member of the family was too much for them to bear, and they conspired to murder Joseph and steal his multicoloured tunic.

Joseph traveled with his brothers to the land of Dothan, unaware of their plot to kill him. Before they were able to enact their wicked plan, Joseph was blessed by a stroke of good luck as a camel caravan of spice traders crossed their path. Joseph’s brother, Judah, proposed that, instead of killing him and stealing the tunic, it would be more profitable to sell Joseph to the traders as a slave. Judah’s greed managed to save Joseph’s life, but it was only the first twist in Joseph’s unpredictable journey.

The spice traders took Joseph to Egypt and sold him to Potiphar, the captain of the Pharaoh’s guard. Potiphar took a liking to Joseph, and put him in charge of his household. However, Potiphar’s wife also took a liking to Joseph and repeatedly attempted to seduce him. Sticking to his strong values, Joseph rejected her advances, leading her to suffer such a great embarrassment that she accused Joseph of trying to seduce her! When Potiphar heard the news, Joseph’s fate was sealed, and he was sent to prison.

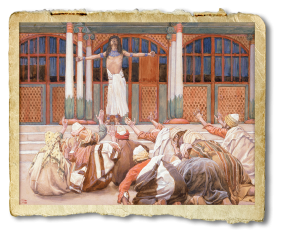

As the years passed by, Joseph developed a reputation in prison for interpreting the inmates’ dreams with remarkable accuracy. As fate would have it, the Pharaoh was puzzled by a dream of his that no sage, magician, or wiseman in all of Egypt could decipher. Word of Joseph’s ability to interpret dreams found its way to the Pharaoh, and Joseph was summoned to interpret the Pharaoh’s dream. In the dream, the Pharaoh witnessed seven plump, healthy cows emerge from the Nile followed by seven starved cows. Then seven robust heads of grain growing from a single stalk were swallowed up by seven thin, weak heads of grain. Joseph interpreted this to mean seven years of abundant harvest in Egypt followed by seven years of famine. Joseph recommended storing one fifth of all the grain for the next seven years in the granaries, grain storages, to prepare for the famine. The Pharaoh was so impressed by Joseph that he appointed him governor of all the land. When the famine struck, Joseph’s plan worked like a charm, and news of Egypt’s success traveled far and wide to other regions suffering from the famine…even to the land of Canaan, and Joseph’s brothers.

Facing starvation in Canaan, Joseph’s brothers set out to Egypt in search of grain. When they arrived, they arranged to meet with the governor of Egypt…their estranged brother Joseph! Upon meeting Joseph, they got down on their knees and bowed to him, just as Joseph’s vision had predicted all those years ago…At the end Joseph forgave them and sent cards loaded with grain to his homeland.

3.1

1.1

2.1

Find the volume of a cylindrical granary of diameter 9 cubits and height 10 cubits. (1 cubit = 52 cm)

3.2

1.1

2.7

Find the volume of a cylindrical granary of diameter 10 cubits and height 10 cubits. (1 cubit = 52 cm)

3.3

1.1

2.7

A cylindrical granary of diameter 9 cubits and height 6 cubits. What is the amount of grain that goes into it? (1 cubit = 52 cm. The hekat was an ancient Egyptian volume unit used to measure grain, bread, and beer. It equals 4.8 litres. 30 hekats equals 1 cubic cubit)

3.4

1.1

2.7

A rectangular granary into which there have gone 7500 quadruple hekat of grain. What are its dimensions? (The hekat was an ancient Egyptian volume unit used to measure grain, bread, and beer. It equals 4.8 litres.)

3.5

1.1

2.2

A rectangular granary into which there have gone 2500 quadruple hekat of grain. What are its dimensions? (The hekat was an ancient Egyptian volume unit used to measure grain, bread, and beer. It equals 4.8 litres.)

3.6

1.1

2.3

Suppose it is said to thee. What is the area of a triangle of side 10 khet and of base 4 khet? (1 khet = 100 cubits, 1 cubit = 52 cm. Assume the triangle is isosceles).

3.7

1.1

2.3

Suppose it is said to thee, What is the area of a cut-off (truncated) triangle of land of 20 khet in its side, 6 khet in its base, 4 khet in its cut-off line? (1 khet = 100 cubits, 1 cubit = 52 cm. Assume the triangle is isosceles).

Mongolia – Genghis Khan

What comes to mind when you think of Genghis Khan? Is he a notorious warlord? A misunderstood visionary? Much like a math problem, a human being is composed of many complex variables, and all must be considered to understand the whole of the equation.

The story of Genghis Khan begins in 12th century Mongolia. Originally named Temujin, he was rejected by his clan at the age of nine, and was taken by his father, Yesukhei, to live with the family of his future bride. On his voyage home, Yesukhei came across a rival Tatar tribe, who tricked him into eating a meal laced with a fatal poison. This left Temujin without a father, without his original clan, but with the plan to one day overcome it all and rule the world…

Temujin slowly developed into a brilliant military strategist. By the age of twenty, he avenged his father’s death by demolishing the Tatar army, ordering the death of every Tatar male over three feet tall. Such brutality gave Genghis Khan a reputation that left his enemies trembling with fear.

Genghis Khan went on to conquer all the land from the Asian edge of the Pacific Ocean to modern-day Hungary in Europe in what became the biggest empire to date. But, it wasn’t his savagery alone that helped him do it. Genghis Khan’s creative vision, unrivaled organizational talents, and his speedy and robust cavalry were all vital aspects of his success. Fear did play a part, however. His army of mounted archers were known to his foes as “the devil’s horsemen.”

Although it’s not possible to know exactly how many people perished at the hands of the Mongol conquests, historians believe that approximately forty million people were killed. Censuses from the Middle Ages show that China’s population dropped by tens of millions, and some estimate that up to seventy-five percent of Iran’s population disappeared as well. Under Genghis Khan, the global population was reduced by roughly eleven percent.

While it might appear that his reign was focused on bloodshed, Genghis Khan also financed advances in medicine and astronomy, as well as a number of construction projects like the extension of the Grand Canal, the palaces in Shangdu (“Xanadu”) and Takht-i-Suleiman, a network of roads and postal stations throughout the empire, and strengthened the vital east-west trade route, “The Silk Road.”

Another remarkable feat of the Mongols was their ability to transform from a nomadic tribe into the administrators of a vast empire in such a short amount of time. Their secret to effective political rule was to allow their conquered territories to operate their everyday affairs as they did before, but with Mongol leaders placed at the top of administrative hierarchies. Beyond his impact on science, infrastructure, war, and politics, Genghis Khan also influenced art and culture. The Mongol empire created a unification of divided lands, allowing artists and craftsmen to travel to different ethnic regions, creating a rich exchange of ideas betweens peoples.

After considering the variables of the human equation that is Genghis Khan, do you see him as a merciless warlord, or as a fearless trailblazer? Or, is it possible that, like in a math problem, one solution can be expressed in a number of different ways?

3.8

1.1

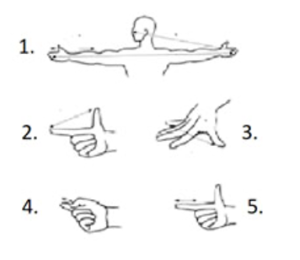

The body of the human and its parts were considered as the most effective scales for measuring in all cultures. The limbs were considered as the best scales for measurement because they allowed instant measurements. You don’t need a ruler! Your ruler is always with you. The following are some old Mongolian units of length. Can you match them with the body parts pictured in the diagram above?

- Huruu 1.5–2 cm

- Yamh 3.5 cm

- üzür sööm 18 cm

- ald 1.6 m

- sööm – 16 cm

3.9

1.1

2.5

The most ancient inscription found so far in Mongolian language is carved onto the stone known as Genghis Khan’s stone. It is dated around 1225 and immortalizes one of Genghis Khan’s warrior’s archery achievement:

“When Chinggis Khan was holding an assembly of Mongolian nobles at Bukha-(S)ochiqai after he had come back from the conquest of the Sartuul people, Yisüngke hit a target at 335 alds.”

- How far is the target in meters?

- Do you think that this feat is achievable?

Europe – Mile, Furlong and Metre

Imagine it is the year 4024. You are a historian trying to learn about life in Canada two thousand years ago. Where would you start? Would you look at “ancient Canadian” art, music, and architecture? While these would all be very revealing aspects of our culture, did you know that math, and units of measurement also shine a very powerful light onto our society’s values?

Think about ancient Rome, for example. Rome was the greatest empire of the ancient world, and it should come as no surprise that one of Rome’s units of measurement was the mile. Why the mile? The word “mile” comes from the Latin phrase mille passus – “one thousand paces of a marching man.” So, since Roman culture was, in many ways, defined by their military conquests, it makes perfect sense that this unit of measurement would have been created as the by-product of the many paces taken during a soldier’s march.

Agricultural societies had units of measurement that reflected their values as well. Let’s look at Britain between the 5th and 11th centuries. The word “acre” describes a plot of land equal to the area of land that could be farmed by one man and two oxen in a single day. Most people at that time worked on farms, so it makes sense that they used the acre as a form of measurement. The same goes for the word furlong. Derived from the Old English words furh (furrow) and lang (long), “furlong” means the length of a furrow: 201 metres, the distance a team of oxen could plough, without resting, in one day. Despite the fact that modern people have lost touch with the origins of these words, “mile,” “acre,” and “furlong” are still vital units of measurement across the English-speaking world and beyond.

Sometimes, units of measurements can also change as the result of cultural revolutions. Did you know that the metric system would never have existed without the French Revolution of 1789? The French revolutionaries made many historic changes: abolishing slavery, giving civil rights to Jews and Muslims, allowing men and women to divorce, and making education available to people of all socioeconomic classes. They even changed their calendar, renamed their months, and made a week ten days instead of seven!

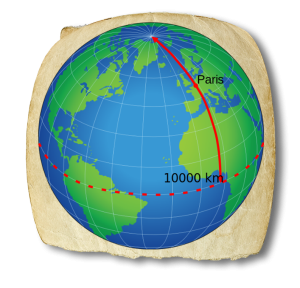

As profound as these changes were, many argue that the most globally significant was the birth of the metric system. In 1790, the French revolutionaries sought to create a new system that was simple, scientific, and a universal constant that would never change. They appointed a commission that invented “the metre,” adapting the name from the Greek word metron, meaning “a measure.” They defined one metre a measurement equal to one ten-millionth of the distance from the equator to the North Pole. In order to figure out this distance, they set out on an expedition in 1792 to determine the “arc” that the earth made in a line between Dunkirk and Barcelona, and after seven long years, finally produced the “metre.”

Human cultures cannot resist the temptation to instill their values into every feature of their civilizations. As a result, we manage to conceive new creations that lead to greater prosperity for all mankind. Only time will tell how the cultural values of the future will innovate the world as we know it. The question remains, do superior forms of mathematical measurement lie ahead?

3.10

1.1

2.6

A basilica is 240 feet long and 120 feet wide. The basilica paved with tiles 23 inches long and 12 inches wide. How many tiles are needed to cover the basilica? (There are 12 inches in a foot.)

3.11

1.1

2.7

A wine cellar is 100 feet long and 64 feet wide. How many casks can it hold, given that each cask is seven feet long and four feet wide, and given that there is an aisle four feet wide down the middle of the cellar?

3.12

1.1

2.7

A four-sided town measures 1100 feet on one side and 1000 feet on the other side; on one edge, 600, and on the other edge, 600. I want to cover it with roofs of houses, each of which is to be 40 feet long and 30 feet wide. How many dwellings can I make there?

3.13

1.1

2.7

I have a cloak 100 cubits long and 80 cubits wide. I wish to make small cloaks with it; each small cloak is 5 cubits long, and 4 wide. How many small cloaks can I make? (1 cubit = 50 cm)

3.14

1.1

2.7

A four-sided field measures 30 perches down one side and 32 down the other; it is 34 perches across the top and 32 across the bottom. How many acres are included in this field? (1 perch ≈5 m. 1 acre = 40 perches by 4 perches ≈ 4000 m2)

3.15

1.1

2.7

There is a triangular city which has one side of 1000 feet, another side of 1000 feet, and a third of 900 feet. Inside of this city, I want to build houses each of which is 20 feet in length and 10 feet in width. How many houses can I build in the city?

Babylon – The Code of Hammurabi

The Babylonian empire was founded over four thousand years ago. It had many inventions in many fields. It included advanced geometry and astronomy, innovations in irrigation and warfare. The Babylonians built some of the most complex and visually stunning canal systems in the ancient world and their engineers knew to the shovelful how much earth was required to build the ramps that packed dirt to the top of a sieged city’s walls. It influenced many elements of the ancient world, and continues to influence modern civilization as well. Many of our beliefs about right and wrong stem from the laws created by the Babylonians. One man, in particular, is credited as the grandfather of the modern legal system. His name is Hammurabi, and he reigned as the king of Babylon from 1792 B.C. to 1750 B.C.

In his forty-two years as king, Hammurabi achieved many notable successes including the transformation of Babylon from a small city-state into an empire. However, none of his military achievements were as important as his ultimate gift to civilization, Hammurabi’s Law Code: a system of two hundred and eighty-two laws carved into a massive finger-shaped black stone pillar called a stele. For the first time, laws were written into stone, suggesting they were unchangeable, even by the king himself!

The gigantic stele was on display for all Babylonians to see so that no one could commit a crime and use ignorance as a defense from punishment.

Here are some examples of laws from Hammurabi’s Law Code:

- “If a man brings an accusation against another man, charging him with murder, but cannot prove it, the accuser shall be put to death.”

- “If a man bears false witness in a case, or does not establish the testimony that he has given, if that case is a case involving life, that man shall be put to death.”

- “If a man bears false witness concerning grain or money, he shall himself bear the penalty imposed in the case.”

Notice how Hammurabi’s laws were the first to include this fundamental legal principle of our current system: the presumption of innocence. A person is presumed innocent of a crime until proven guilty in a court of law. Can you imagine living in a world where you were considered guilty of a crime and had to prove your innocence? We have Hammurabi to thank that it doesn’t work that way. And, we’re not alone. 6th century Roman law, and 15th century Islamic law both adopted the same principle.

On top of protecting the rights of innocent citizens, Hammurabi’s law code also built in safeguards to ensure judges oversaw court cases fairly. Considering the following law:

- “If a judge pronounces judgment, renders a decision, delivers a verdict duly signed and sealed, and afterward alters his judgment , they shall call that judge to account for the alteration of the judgment which he has pronounced, and he shall pay twelve-fold the penalty in that judgment; and, in the assembly, they shall expel him from his judgment seat.”

With artwork of Hammurabi decorating the halls of the U.S. Supreme Court, and Capitol building, it’s obvious that he’s had a profound influence on the past and present. And, although other legal texts written before Hammurabi’s Law Code have been discovered, none have had the same lasting impact on global civilization. Like his law code, forever carved in stone, Hammurabi’s legacy stands firmly as one of a pioneering lawmaker who aspired to – in the words of his monument – “prevent the strong from oppressing the weak and to see that justice is done…”

3.16

1.1

2.6

A little rectangular canal is to be excavated for a length of 5 km. Its width is 2 m, and its depth is 1 m. Each laborer is assigned to remove 4m3 of earth, for which he will be paid one-third of a basket of barley. How many laborers are required for the job, and what are the total wages to be paid?

3.17

1.1

2.7

A canal is 5 rods long, 11/2 rods wide, and 1/2 rod deep. Workers are assigned to dig 10 gin of earth for which task they are paid 6 sila of grain. What is the area of the surface of this canal and its volume? What are the number of workers required and their wages? (1 rod = 12 cubits = 12 x 50 cm= 6 m, 1 sar area = 36 m2, 1 gin = 5 litres, 1 sila = 1 litre)

3.18

1.1

2.7

A siege ramp is to be built to attack a walled city. The volume of earth allowed is 5400 sar. The ramp will have a width of 6 rods, a base length of 40 rods, and a height of 45 cubits. Construction of the ramp is incomplete; an 8-rod gap is left between the end of the ramp and the city wall. The height of the uncompleted ramp is 36 cubits. How much more earth is needed to complete this ramp? (1 sar volume = 1 sar area x 1 cubit =18 m3 , 1 cubit = 50 cm; 1 rod = 12 cubits = 6 m)