Chapter 3 – Resistance to Colonization

Overview

Medicine Wheel Direction – South (Red) – Time and Relationships

The teachings of Zhawaanong (the south) include: Time, relationships, youth, and patience. The positive side of the medicine wheel talks about creating good relationships. It takes time to build good relationships with people (Nabigon, 2006). The opposite of building good relationships is described as envy. When people are envious, they are said to want to have what others have but are not willing to work for it. Therefore, to build good relationships one must work for it. Indigenous people have worked hard to create spaces where they can use the gifts that have been given to them – traditions, culture, healing practices, governance systems, and ways of being and knowing. Many non-Indigenous people are drawn to the services offered by Indigenous organizations because of their holistic approaches and their ability to provide culturally relevant programs and services.

Youth are also represented in the southern direction. Adolescence is a time of change – physically, emotionally, spiritually and mentally. Adolescents are in a stage of puberty where bodies are going through many physical changes. This is a time when adolescents are exploring who they are as individuals. The exploration of new relationships and the maintenance of current relationships can be emotionally challenging. Youth are looking for meaning and purpose in life. Traditionally, youth would fast or go on a vision quest to learn about what their role in life would be. At this stage of life, youth become distant from their parents and often challenge their authority. Fortunately, there is a special relationship between the youth and their elders/grandparents. Their elders/grandparents have lived their lives and can draw upon their knowledge and experiences to help youth through this transitional period in their life.

The development of Indigenous organizations has also gone through a similar sort of transitional period from when they were first developed to creating an identity for themselves and developing relationships with the communities that they serve. They have had many lessons in patience as they were developing. Patience with the funding agencies who may not have understood what the agencies were trying to achieve with the development of culturally relevant programming. Often times, these agencies would seek the advice and guidance from their elders to guide the development of their programs. These elders would also provide feedback about how to incorporate their teachings into the programs.

This chapter will look at how Indigenous people have worked to create spaces for people to learn about traditions and culture: traditional healing practices, Indigenous governance systems, Indigenous knowledge systems and Indigenous ways of being. The movement towards greater Indigenous control of programs and services began in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Indigenous people were beginning to organize themselves in response to the growing need for programs and services to respond to the specific needs of their populations. For example, the establishment of the Ontario Federation of Indian Friendship Centers came about as a result of need to provide basic needs (food, clothing and shelter) to growing Indigenous populations in urban settings in Kenora, Thunder Bay, Toronto, London, Parry Sound and Red Lake, Ontario. This group, known as the “original six,” was instrumental in establishing Friendship Centers in Ontario (OFIFC, 2013). Likewise, in the late 1970s and the early 1980s, Indigenous communities concerned over the mass removal of Indigenous children from their homes and communities, the blatant disrespect for tribal authority, and the disregard for Indigenous culture that led to the deterioration of Indigenous family systems began developing their own child and family service agencies (Weechi-it-te-win Family Services, 2018b). Similarly, the Aboriginal Health Access Centers were established in 1994 in response to growing concerns about the systemic health disparities and inequities within the Indigenous population across Ontario.

This chapter will look specifically at the programs and services that are located in the Greater Sudbury and Manitoulin Areas. Learning about the scope of services that are available to Indigenous peoples of this territory and the ways that these services have been able to respond to the impacts of colonial history can create a sense of pride in Indigenous students, faculty and staff and de-mystify some of the stereotypes that exist about Indigenous peoples, programs and services.

Learning Outcomes

When you have worked through the material in this chapter, you will be able to do the following:

- Identify and locate traditional Indigenous spaces in the area.

- Discuss the impact of these spaces using examples.

- Explain why these spaces are important for Indigenous and non-Indigenous people.

- Reflect again on your current knowledge of Indigenous peoples.

Geographical Setting and sources of information

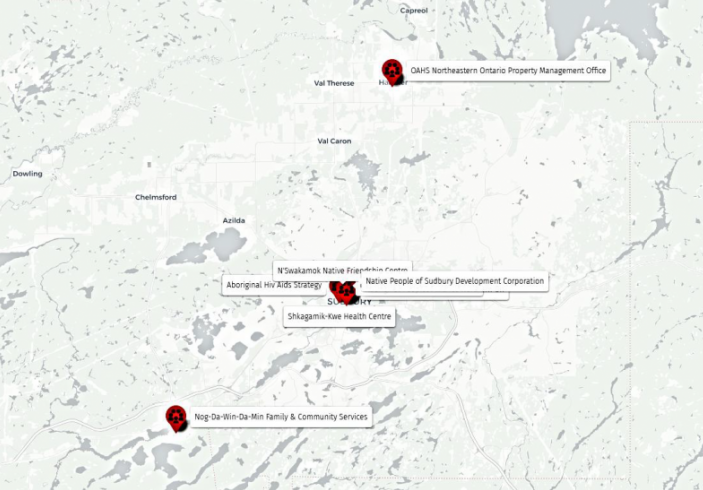

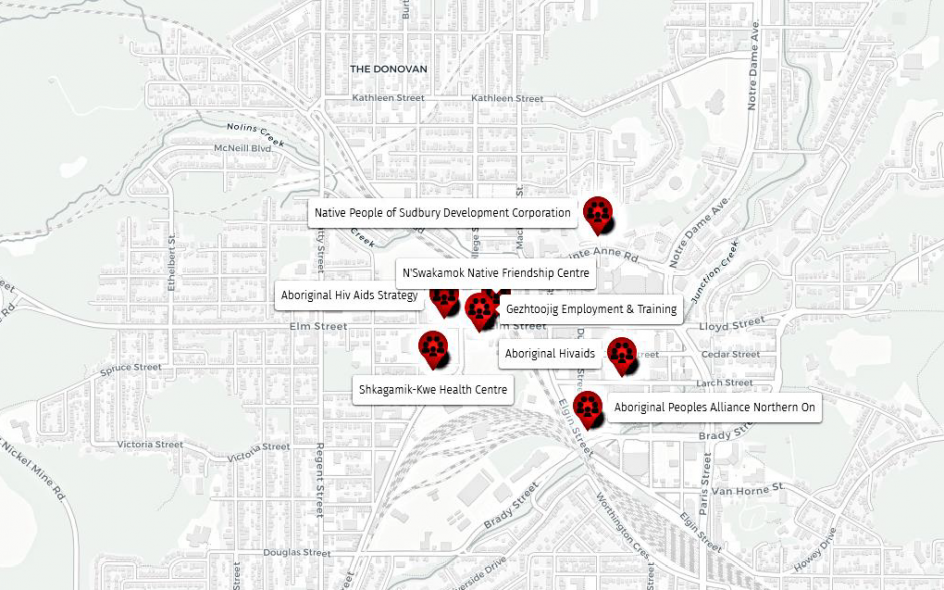

The image below is a snapshot of the various Indigenous services currently operating in Greater Sudbury. The second image is a zoomed-in snapshot of the various Indigenous services currently operating in the Sudbury Region.

Click on the images of the maps below for a more detailed geographic context.