25 Startup Funding: Crowdfunding

CJ Cornell

Crowdfunding, which barely existed a few years ago, spread to every aspect of society—from funding creative projects, local civic projects to causes and charities, and of course—funding startup companies. Today, crowdfunding is an essential part of every entrepreneurship conversation.

Modern crowdfunding has the following haiku-like definition:[1]

- An individual or organization,

- on behalf of a cause, a project, a product, or a company,

- solicits and collects money,

- usually in relatively small amounts,

- from a large number of people,

- using an online platform,

- where communications and transactions are managed over electronic networks.

Crowdfunding is one of the great movements of the twenty-first century, and one of the most powerful. Still in its infancy, crowdfunding moved beyond Kickstarter-like passion projects and became a major new and disruptive force in investment funding. And just in the last few years, the crowdfunding movement impelled the U.S. Congress, state legislatures in all 50 states and the Security Exchange Commission to overhaul investment laws that existed since 1934.

Broadly defined, crowdfunding is collecting small amounts of money from a large number of people. With the advent of social networks (abundance of people on the network), crowdfunding only recently became practical. But the concept has been around for centuries—except that with crowdfunding, the people willingly contribute money for a project, product, or cause that they believe in.

Crowfunding—a Little History

The concept of crowdfunding is old. What’s new is applying technology—social networks—to the process. This allows interested supporters from around the globe to support any project, anywhere, as long as they share passion and see merit in the project’s goals.

In the early 1880s, France gave the United States a gift: the Statue of Liberty. It was shipped to New York City where remained packed in crates for over a year. Why? The New York state government would not allocate the $200,000 required to build and mount the statue onto a pedestal (today this would be over $2.5 million). Newspaper mogul Joseph Pulitzer ran a fundraising campaign through his “New York World” tabloid—offering to publish the name of everyone who donated, to the front page. Donors also would get little rewards: $1 got you a 6-inch replica statue and $5 got you a 12-inch statue. The campaign went viral. Within six months of the fundraising appeal, the pedestal was fully funded, with the majority of donations being under a dollar.

But this was not the first crowdfunding campaign. For centuries, book authors have appealed to the crowd for funding. Kickstarter (the largest crowdfunding site) proudly recounts one of the earliest examples:[2]

In 1713, Alexander Pope (the poet) set out to translate 15,693 lines of ancient Greek poetry into English. It took five long years to get the six volumes right, but the result was worth the wait: a translation of Homer’s Iliad that endures to this day. How did Pope go about getting this project off the ground? Turns out he kind of Kickstarted it.

In exchange for a shout-out in the acknowledgments an early edition of the book, and the delight of helping to bring a new creative work into the world, 750 subscribers pledged two gold guineas to support Pope’s effort before he put pen to paper. They were listed in an early edition of the book.

A Boon for Entrepreneurs

Entrepreneurs discovered crowdfunding as an efficient and exciting method of funding innovative product ideas that were too early for investors. Instead, they reached out to like-minded supporters, early adopters, and technology fans, who were enthusiastic about backing early stage ideas. The crowd not only contributes money to develop the product—but the crowd offers something just as valuable: early market validation for the product, and a chance for the entrepreneur to build reputation and credibility.

Backers embraced rewards-based sites like Kickstarter and Indiegogo because they offered a model that was both engaging and lower risk. Potential contributors discussed the merits of the project or product with each other and with the founders; they were allowed to pre-commit to donations at specific, nominal levels—typically $5, $25, $100, $250—with each level of contribution receiving different rewards. This pre-commitment was important. It amounts to a binding pledge. The entrepreneur sets a funding goal and a time limit. If the pledges meet the funding goal within the time limit, everyone gets charged. Otherwise, no money changes hands. For early backers, this was a critical feature getting them to embrace crowdfunding.

Later, as backers get more comfortable with crowdfunding, other methods of contributing proliferated.

[Note: Use the slide bar to navigate the below chart on the web book. This will get better soon!]

The Many Facets of Crowdfunding

| Donation

Crowdfunding |

Rewards-based Crowdfunding | “Pre-order” Crowdfunding | Debt

Crowdfunding |

Equity Crowdfunding | |

| Overview

|

Charities and causes. Usually for individuals and smaller organizations | Donors get token rewards as part of their contribution. Usually used for projects in the arts, entertainment and community/civic projects | Similar to rewards-based crowdfunding, except the donations are made with the expectation that the backers will receive early versions of the product that they are funding | A.k.a. “peer to peer,” “P2P,” “marketplace lending,” or “crowdlending.” Funding is aggregated into a loan, that will be paid back to the contributors. | The general public invests small amounts in return for stock. |

| Typical Range | Under $10,000 (often under $2,000) | Varies widely. Average $7-10K per project. But many attract $50-$100K | Varies widely; many projects attracting over $100K, to $1-$5M | From “microloans” for small business >$2,500, to traditional loans in $10k – $500k range subject to personal credit approval. | Brand-new SEC regulations. While companies can raise as little as $100k this is really only practical for over $500K to $5M or greater given the level of fees and preparations required. |

| Prominent

Platforms[3] |

GoFundMe, CrowdRise | Kickstarter, Indiegogo | Kickstarter, Indiegogo | Funding Circle, Lending Club, Prosper, Kiva | AngelList, Crowdfunder, CircleUp, Gust[4], Seedrs, Fundable, Indiegogo

|

| Typical Candidate Projects

|

Charitable causes, events | Creative projects, events | New product innovations | Small business | Established startups (post-seed) |

| Advantages (for entrepreneurs) | Allows entrepreneurs to efficiently solicit funding from friends and family (who primarily want to help the entrepreneur, personally) | Solicits funding from advocates passionate about the idea, as well as feedback and advice | Pre-order (advance sales) provide valuable market validation as well as product funding. | Funding for small businesses that otherwise would not qualify for bank loans | Circumvents the venture capital industry and allows for raising significant funding by going directly to the public |

| Disadvantages (for Entrepreneurs)

|

Practical for small amounts only | Practical for nominal fundraising, but does not always prove customer demand for a specific product. | Pre-order commitments can be very risky (selling a product that does not yet exist). | P2P lending requires repayment, and usually personal guarantees. | Significant overhead costs in preparing. Regulations still in flux |

Hundreds of crowdfunding platforms emerged since the early success of Indiegogo (2008) and Kickstarter (2009). It is not necessary to use a third-party platform. Individuals or organizations can raise funds using their own websites, but they still need to incorporate tools for sophisticated payment processing, managing contributors—and attracting a crowd.

Hybrids and new categories are emerging: royalty-based crowdfunding—allowing backers to receive royalties from the product they funded, and litigation crowdfunding—allowing backers to fund a lawsuit in return for a stake in any resulting monetary judgments.

Today, the latest numbers show worldwide crowdfunding raised approximately $35 Billion in 2015 with the vast majority, approximately $25 Billion, being debt. Crowdfunding followed by over $5 Billion for donation/reward-based crowdfunding.[5]

But those figures are for all kinds of crowdfunding campaigns—including those that are for charity, community, and personal projects. To get a sense, realistically, of the kind of projects that are funded through the most popular crowdfunding platforms, let’s take a look at Kickstarter—who publishes their data, real-time, for all to see:

Kickstarter Stats

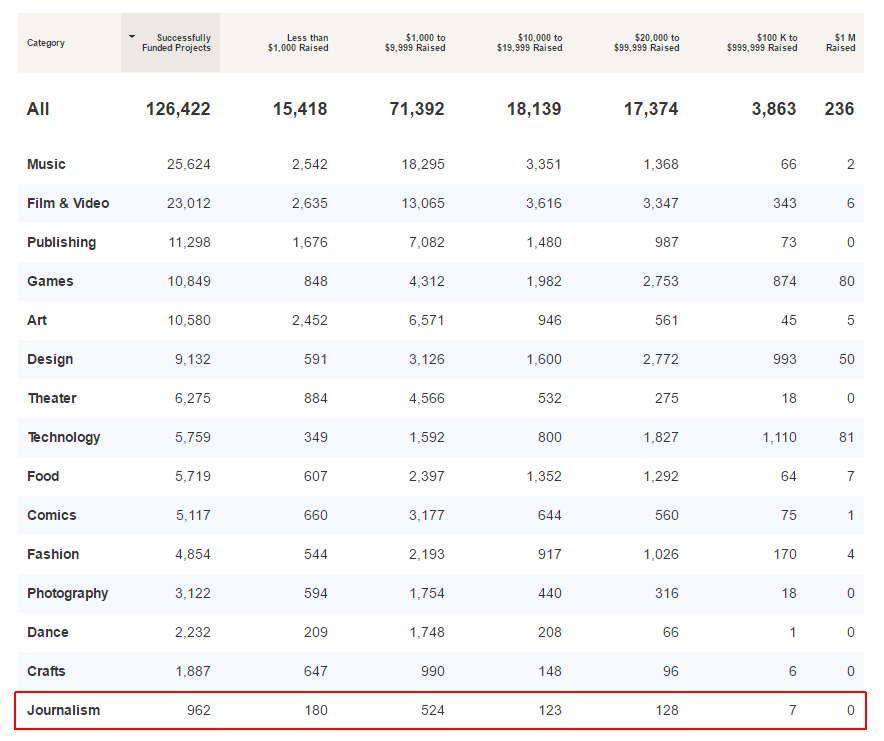

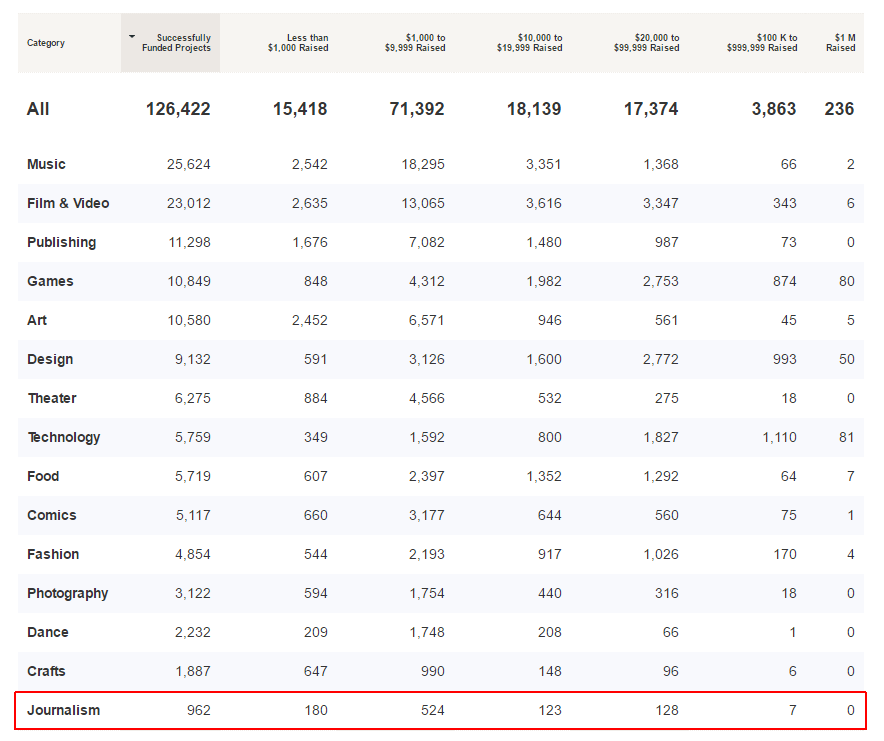

Kickstarter provides raw stats about projects funded on its platform, representing the site’s all-time figures since it launched in 2009, and updates this data every day. View the data at https://www.kickstarter.com/help/stats[6]. Below is a summary of the data as of June 12, 2017:

| Total dollars pledged to Kickstarter Projects | $3,096,331,221 |

| Successfully funded projects | 126,396 |

| Total backers | 13,043,973 |

| Repeat backers | 4,185,194 |

| Total pledges | 38,692,691 |

Successfully Funded Projects

According to Kickstarter, the majority of successfully funded projects raise less than $10,000, but a growing number have reached six, seven, and even eight figures. Currently funding projects that have reached their goals are not included in this chart—only projects whose funding is complete.

In other words—while there are indeed several multimillion-dollar crowdfunding success stories, most campaigns—particularly first-time crowdfunding campaigns—bring in a far more modest figure. For entrepreneurs seeking crowdfunding, well, expectations should be aligned with reality.

Journalism and media entrepreneurs should notice that, since Kickstarter’s inception, a total of 962 journalism projects successfully raised money through crowdfunding, with the majority of those raising less than $10,000.

Technology products fare better—but those are usually consumer hardware (electronic) products. Arts projects (Film, Video, Music, Art, Design, Theater and photography) garner the lion’s share of the crowdfunding donations on Kickstarter.

For entrepreneurs, it’s important to note:

- Crowdfunding is usually most effective for startup companies who are able to deliver a tangible product. Backers donate money in return for “rewards” are really pre-orders for a physical product.

- Service businesses and consulting businesses have little chance of being funded on typical crowdfunding sites.

Regardless of the risks and limitations, crowdfunding remains a powerful new way to fund new companies and new projects. But it’s not free money or easy money. Attracting money from the crowd takes significant preparation and significant work. However, unlike other forms of funding, the steps are largely under your control.

Basics of a Crowdfunding Campaign

- Kickstarter, currently the most popular crowdfunding platform, enables “project creators” to post project or product descriptions and videos in order to solicit funding (in the form of “pledge” contributions).

- Project creators set a fundraising goal and a deadline, usually 30-90 days (with the average being 45-60 days).

- Using social media and other promotional techniques, the project owners attempt to engage advocates and supporters who pledge relatively small amounts of money.

- The project creators offer token “rewards” as incentives for contributors to donate to the project. If the total amount of the pledges meets or exceeds the goal, before the deadline, then the “pledges” are automatically collected from the donors.

- Kickstarter crowdfunding campaigns are “all or nothing”: If the target funding goal is not met by the deadline, then no money changes hands.

- Indiegogo is a platform that allows for an all-or-nothing campaign, or a “flexible funding” campaign: where the money pledged is awarded to the campaign at the end of the time limit, regardless if the goal was met.

Notable Crowdfunding Campaign Techniques and Tips

Indiegogo CEO Slava Rubin offers a few critical tips and tricks for those looking to crowdfund successfully.[7]

- Rubin notes how important pitch videos are to campaigns: “Campaigns that feature videos—about the startup and the products—typically raised 114 percent more money on Indiegogo compared to those that don’t.”

- Discussing how “word of mouth” is important to campaigns, Slava shared: “Get your inner circle of friends, family and customers to fund you and to spread the news about the campaign. This will get the momentum going.”

- Noting that organizers should stay in contact with backers, the CEO and co-founder of the platform stated:

- “Campaigns that provide updates every five days raised twice as much as those that update every ten days or more.”

Yancey Strickler, CEO of Kickstarter, points out that Kickstarter campaigns that reach the 20 percent mark have an 82 percent success rate. If you reach 30 percent, you have a 98 percent chance of reaching your goal.[8]

“Think about that: with less than a third of your goal funded, you have a 98 percent chance of success. These inherently lopsided results require a lopsided approach: you should be putting the vast majority of your efforts on the early or even very—early portion of your campaign.”[9]

The implication here is that you shouldn’t promote a campaign with 10 percent or 12 percent funding to strangers. This also includes Facebook fans, blog readers, or your existing user base. This sounds counterintuitive, but even a die-hard fan can be off-put by poor crowdfunding performance. It’s one thing to mention your new campaign, with one or two small posts, but don’t waste these high-quality leads early on. Save them for when they’ll help the most: maybe before 50 percent, but definitely after you’ve reached a respectable 20-25 percent.”[10]

- Your first step is to figure out your target audience at least a month before your campaign is scheduled to go live.

- Campaign owners often try to target everyone around them (friends, family, co-workers, etc.) because they don’t invest enough time to identify their target audience which gives them vastly expanded reach.

- This lack of focus is certainly not the most efficient way to market a crowdfunding campaign. In order to determine the target audience for your campaign stop and think about WHO can benefit from your product or your service.[11]

Then zero in on key demographics of this audience by considering the age range, gender, income, and education level (as applicable) of the pool of potential crowdfunders who could or would back your project.”

Lessons for Entrepreneurs from Crowdfunding

Kauffman Dissertation Fellow Ethan Mollick at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School examined almost 47,000 projects on Kickstarter that raised a combined revenue of $198 million.[12] Mollick concluded that several factors influence whether a project will succeed or not:

- The greater the size of the founder’s social network, the greater the chance for success (particularly Facebook in this case; this is also known as the “be popular” strategy).

- The underlying quality of the projects—those with high-quality, polished pitches are more likely to be funded (e.g., use a video; as Kickstarter’s website states, “Projects with videos succeed at a much higher rate than those without”).

- A strong geographic component tie-in seems to increase success (pitching country music in Nashville, film in Los Angeles, etc.).

- A shorter Kickstarter duration is better (35 percent chance of success for 30-day pitches, 29 percent for 60-day pitches). Mollick noted that a longer duration implies a lack of confidence in the project’s success.

- Being highlighted on the Kickstarter website is hugely beneficial (89 percent chance of success vs. 30 percent for unfeatured projects).

- A large number of creative individuals in the city where the project is based is associated with greater success (target these kinds of people).

Research Study from Indiegogo: Crowdfunding Campaign Stats

Indiegogo took a look at the numbers and statistics behind 100,000 Indiegogo campaigns to see what’s working and what’s not. They offered several tips for campaigns.[13]

- They suggest 30-day campaigns. Of successful campaigns they analyzed, roughly a third lasted between 30 and 39 days.

- Keep updating your campaign page throughout your campaign with progress updates, newly added perks and other successes. Contributors get notified by email when you update the campaign, so this is an important way to keep your funders engaged. Indiegogo suggests updating your campaign at least four times.

- Indiegogo found that of the 100,000 campaigns they looked at (including those that didn’t meet their goals), 42 percent of funds were raised in the first and last three days. Be ready to start and finish strong.

- Their stats showed that successful campaigns added an average of 12 new perks to their campaigns after they launched.

- Don’t go solo—campaigns with a team behind them and therefore many networks to leverage were more successful.

- Stats showed that campaigns with video raised four times the funds as those without. So be sure to include this crucial marketing element.

- Don’t limit your efforts to a U.S. audience. The United States, Canada, United Kingdom, Australia and Germany were the top five contributing countries to the campaigns analyzed.

![]() Assignments / Discussion: What are the most successful crowdfunding campaigns of all time? What do they have in common? Search for current and successfully completed crowdfunding campaigns in journalism and media. Discuss what works and what doesn’t work. Discuss specific strategies that would improve the success of journalism and media crowdfunding campaigns.

Assignments / Discussion: What are the most successful crowdfunding campaigns of all time? What do they have in common? Search for current and successfully completed crowdfunding campaigns in journalism and media. Discuss what works and what doesn’t work. Discuss specific strategies that would improve the success of journalism and media crowdfunding campaigns.

Equity Crowdfunding

Until very recently—under antiquated U.S. securities laws—it was illegal to offer equity (stock) to anyone in the crowd. But then the crowd became a movement, and made history.

Now, crowdfunding is also poised to become a growing source of earliest stage equity financing following passage of the JOBS Act in April 2012. The JOBS Act enabled investors to use the Web and social media to make investments in entrepreneurs and small and medium companies.

On April 5, 2012 President Barack Obama signed the Jumpstart Our Business Startups Act (JOBS Act)—a bipartisan bill that was specifically designed to open the floodgates of funding for emerging growth companies. After nearly four years of regulatory wrangling, the Securities and Exchange Commission released the final rules, taking effect on May 16, 2016.

Equity crowdfunding is the category with all eyes watching. Not only does the new law allow for just about anyone to invest in, not just donate to an emerging startup company—it allows startups to publicly solicit from the crowd. Until May 2016, all this was illegal. Until then, startups had to make the rounds with VCs and Angels, educate them about their industry, pitch, get “warm” introductions. Up until then, an engineer, for instance, who might have recognized the unique potential of a nascent Kickstarter product, could not invest because she wasn’t an “accredited” investor. The VCs and Angels were allowed to become millionaires, but experts who could spot the early potential were not.

The World Bank forecasts a global crowdfunding market of $96 billion by 2025[14]—far more than venture capital and angel funding combined.

Spot.us—Honorable Mention

Before Kickstarter or Indiegogo existed, there was Spot.us.

Founded in 2008 by a young—but experienced—journalist named David Cohn[15], Spot.us was an online product and a company. It no longer exists, yet Spot.us was one of the most important experiments to emerge from the Knight News Challenge.

Spot.us pioneered community funded reporting: crowdfunding for journalism. Today, this is an easy concept to digest—but in 2008 a lot of people had a hard time understanding the concept. It’s the innovator’s curse.

Stories began as tips from the public giving an issue they would like to see covered, or pitches from a journalist to create a story, including the amount of money needed. Visitors to the website could then donate to fund the pitch.[16]

If, for instance, a local citizen wanted to see an investigative story on the mayor’s past business ties with a contractor, they would post the idea to Spot.us. A journalist browsing the site might be intrigued, and would agree to research and write the story, for an estimated $5,000. People in the community would pledge or donate $20 or $50 each. When the total was met, the journalist would write the story. News organizations could obtain exclusive rights by contributing greater than 50 percent of the funding.

Without this kind of mechanism, important stories and investigative reports might never have seen the light of day. Many services today for freelance writers and creatives—particularly crowdfunding sites—owe their existence to the trailblazing efforts of Spot.us.

Resources

Instructor Resources

For faculty wanting to bring first-hand expertise on funding into their classroom, consider inviting guests including:

- outside speakers

- angel investors / a local angel group

- local VCs

- a local startup entrepreneur—who has raised venture funding (… try to avoid lawyers, consultants, accountants etc … )

Require students to make a grant application to a journalism foundation or set up a Kickstarter campaign during the course of the semester.

CJ Cornell is a serial entrepreneur, investor, advisor, mentor, author, speaker, and educator. He is the author of the best-selling book: The Age of Metapreneurship—A Journey into the Future of Entrepreneurship[18] and the upcoming book: The Startup Brain Trust—A Guidebook for Startups, Entrepreneurs, and the Experts that Help them Become Great. Reach him on Twitter at @cjcornell.

Leave feedback on this chapter.

- Cornell, CJ, The Age of Metapreneurship, (Phoenix: Venture Point Press, 2017), 197—199. https://www.amazon.com/dp/069287724X. ↵

- Justin Kazmark, "Kickstarter Before Kickstarter," Kickstarter, July 18, 2013, https://www.kickstarter.com/blog/kickstarter-before-kickstarter. ↵

- Note that many platforms allow for more than one type of crowdfunding type: e.g., Kickstarter allows for rewards and pre-orders; Fundable allows for equity and rewards. ↵

- Gust, founded by super-angel David Rose, was originally a platform exclusively for angel investors and angel groups, but has recently expanded into equity crowdfunding, fortified by a host of support services for companies and investors—including due diligence, financials, and cap tables. ↵

- "Crowdfunding Industry Statistics 2015-2016," CrowdExpert.com, http://crowdexpert.com/crowdfunding-industry-statistics/. and Anthony Zeoli, "Crowdfunding: A Look at 2015 & Beyond!” Crowdfund Insider, January 05, 2016, http://www.crowdfundinsider.com/2015/12/79574-crowdfunding-a-look-at-2015-beyond/. ↵

- Kickstarter Stats, Accessed June 12, 2017, Kickstarter, https://www.kickstarter.com/help/stats. ↵

- Samantha Hurst, “Brief: Indiegogo’s Slava Rubin Offers up Tricks for Crowdfunding Success,” Crowdfund Insider, August 27, 2015, https://www.crowdfundinsider.com/2015/08/73438-brief-indiegogos-slava-rubin-offers-up-tips-tricks-for-crowdfunding-success/. ↵

- “How to Reach Your Crowdfunding Tipping Point,” Trustleaf on Medium, April 30, 2014, https://medium.com/on-small-businesses/how-to-reach-your-crowdfunding-tipping-point-d418aa1a2853. ↵

- “How to Reach Your Crowdfunding Tipping Point,” Trustleaf on Medium, April 30, 2014, https://medium.com/on-small-businesses/how-to-reach-your-crowdfunding-tipping-point-d418aa. ↵

- “How to Reach Your Crowdfunding Tipping Point,” Trustleaf on Medium, April 30, 2014, https://medium.com/on-small-businesses/how-to-reach-your-crowdfunding-tipping-point-d418aa1a2853. ↵

- “Build the Crowd Before Starting Your Crowdfunding Campaign,” Crowdfund Buzz, June 4, 2014, http://www.crowdfundbuzz.com/build-crowd-starting-crowdfunding-campaign. ↵

- Ethan R. Mollick, "The Dynamics of Crowdfunding: An Exploratory Study," Journal of Business Venturing 29, no. 1 (January 2014): 1-16. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2088298. ↵

- Amy Yeh, "New Research Study: 7 Stats from 100,000 Crowdfunding Campaigns," Indiegogo Blog, https://go.indiegogo.com/blog/2015/10/crowdfunding-statistics-trends-infographic.html. ↵

- “Crowdfunding’s Potential for the Developing World,” Information for Development Program infoDev / The World Bank, November 18, 2013, http://funginstitute.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/Crowdfundings_Potential_for_the_Developing_World.pdf. ↵

- Digidave, http://blog.digidave.org/about. ↵

- “Spot.us,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spot.us. ↵

- KickTraq, https://www.kicktraq.com. ↵

- Cornell, CJ, The Age of Metapreneurship, (Phoenix: Venture Point Press, 2017). https://www.amazon.com/dp/069287724X. ↵