4 Taking Risks and Building Resilience on the Path to Innovation

Dana Coester

Finding Joy in Taking Risks

“We don’t know what will happen, but let’s try this!”

Resiliency—the ability to weather change and bounce back from failure—is an essential mindset for entrepreneurs. In innumerable blog posts and articles, industry leaders describe resilience as a cornerstone to innovation, frequently citing Thomas Edison’s famous quote: “I have not failed. I have just found ten thousand ways that won’t work.”

Resilience is more than a buzzword; it’s a survival skill. And it’s a skill that you will need to develop to become successful at navigating today’s dynamic business environment. With predictions suggesting that today’s worker may hold more than twelve jobs in their lifetime, you will need to build your capacity for resilience for the future. Sometimes you are forced to be resilient when dealing with an uncertain or difficult situation, such as losing your job or having to relocate. But while life experiences lay the groundwork, here are a few additional perspectives you can explore to build on your core of resiliency.

“The future is on top of us.”

One of the first steps in building resiliency is to fully appreciate the magnitude and pace of change that technology drives across almost all fields. This insight will even give you an edge over entrenched leaders, who continue to underestimate the pace of change[1] in their industries. Read carefully and internalize this bold statement about exponential change from Ray Kurzweil’s now cult-classic 2001 essay, Law of Accelerating Returns:[2]

“Human culture will change in the next 100 years as much as it has changed in the past 25,000 years.”

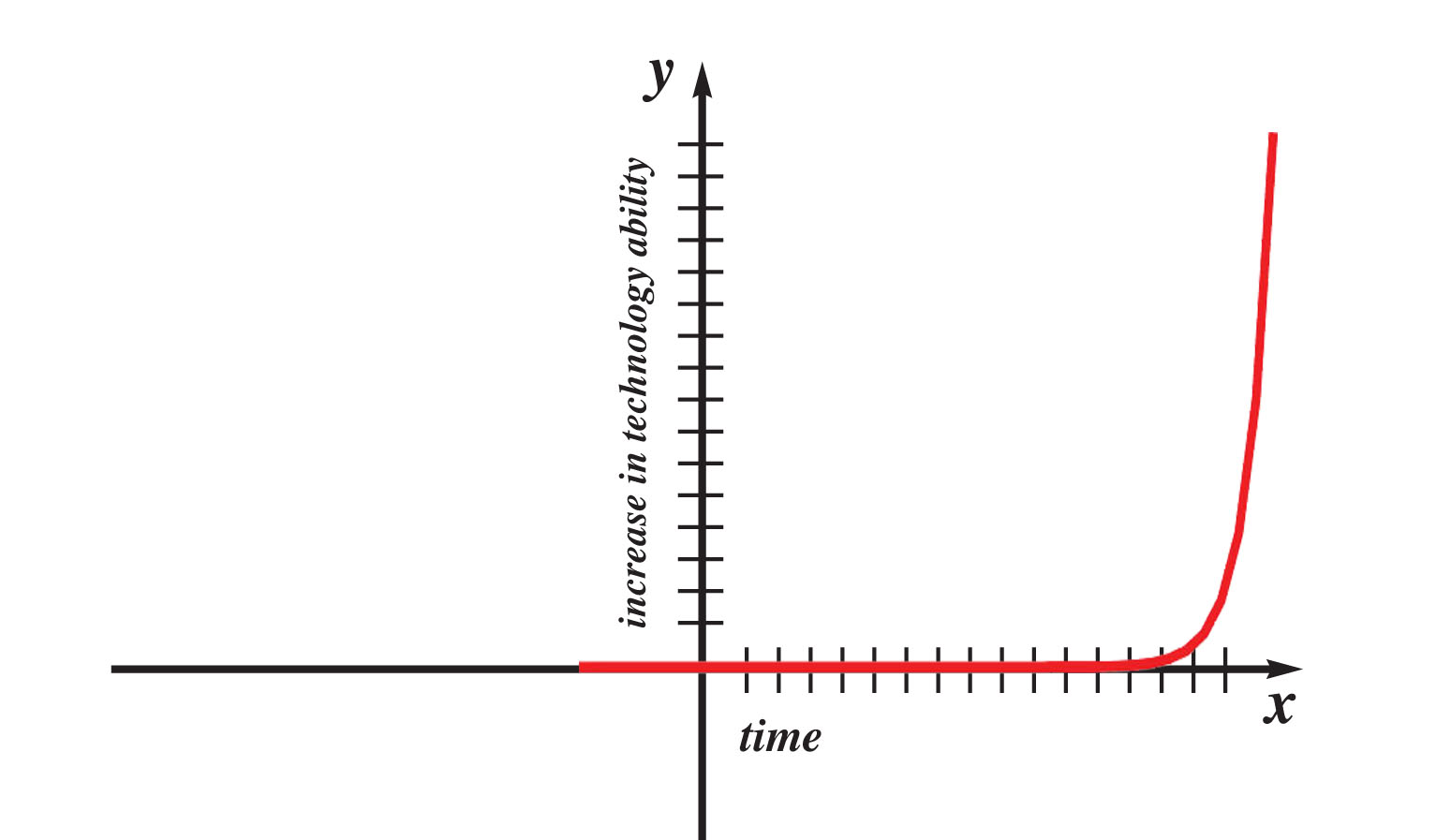

According to Kurzweil, the default setting within organizations for anticipating change is based on an intuitive linear view of progress—the idea that change happens at a steady and predictable pace with just a few dramatic turns. This false perception results in consistently underestimating change, which can happen at a far more accelerated rate. In fact, Kurzweil described the far-reaching implications of what the “acceleration of acceleration” would mean for industries grappling with technology-driven change, anticipating the profound disruption to come in the years since 2001.

The gist is that all exponential change is flat for a very long period of time—but exponential change always reaches a point where the graph becomes vertical.

We are at the point where the curve goes vertical.

You may ask, why does 100 years from now matter if you’re just looking to start your own business a few years from now? If you were on this curve back in 1980, and you were making plans for your future, you can see that the location of the future was exactly where you’d expect it—far off on a gentle and still relatively flat slope.

But if you’re at the point where the graph becomes vertical, you need to ask yourself, “Where does the future lie now?”

A young media college student in an entrepreneurship class recently answered that question, by saying: “The future is on top of us.”

“We don’t know what will happen.”

John Keefe, a “bot developer” and product manager at innovative startup publication Quartz,[3] teaches classes in innovation and evangelizes “DIY hackery” as part of the maker community. The maker movement represents a thriving community of hobbyists and entrepreneurs alike who conduct home-grown, DIY experiments in technology and product development as well as other creative problem solving that helps drive innovation across industries.

Keefe says experimenting take takes trial and error, and that innovation by nature is a risky prospect. He challenged himself to risk failure repeatedly in his public experiment “Make Every Week,”[4] where he built a new DIY “thing” (almost) every week for a year.

“Being creative might lead to failure,” Keefe says, “but it could lead to something awesome.”

Fellow Innovator-in-Residence Sarah Slobin, formerly of Quartz, currently at Reuters, echoed this failure-friendly mindset as she led a team of students to produce a mobile-first reporting project…before there were any models for mobile-first reporting. At a particularly rough moment when uncertainty about project outcomes was at a peak, the students’ engagement and enthusiasm faltered. Slobin took a tough-love approach AND shared her own vulnerability. She called a time-out with the class and challenged them: “Do you think when I come into work every day that I know exactly what’s going to happen or that I know exactly what I’m doing or how to do it? What are you afraid of?” There’s no place for fear of failure in innovation, she said. “If you see failure on the horizon…run toward it.”

In Keefe’s case, being creative led to breakthroughs in groundbreaking sensor journalism,[5] new job opportunities and a book,[6] but it was also a valuable exercise in acclimating himself to taking risks. Not unlike embarking on an exercise regime, acclimating yourself to potential failure through repeated exposure to trial and error on a small scale helps build resilience.

For Keefe, these serial experiments included working with students on a beta sensor-reporting project as part of an experimental journalism class he taught at West Virginia University. Each week he said to students:

“We don’t know what will happen…but let’s try this.”

As simple as that statement seems, it bears breaking down and repeating, because it captures attributes of innovation you can start to emulate now. When you say out loud to your classmates or teammates, “We don’t know what will happen, but let’s try it,” you are helping to build a culture of resiliency and a safe space to experiment in that moment. Here’s how:

“We don’t know what will happen…” expresses:

- a matter-of-fact expectation that uncertainty is a given

- a transparent acknowledgement of vulnerability without anxiety or shame

- that you’re willing to risk asking questions that don’t have answers

“But let’s try it…” expresses:

- an eagerness to conduct hands-on experimentation

- a commitment to being collaborative and inclusive

- joyful curiosity

Confronting the reality of accelerating change empowers you to prepare for a different kind of future than the one your predecessors faced. Building resiliency gives you a remarkable edge for both anticipating, and navigating, the many changes to come.

Dana Coester is an associate professor at West Virginia University Reed College of Media, where she is creative director for the College’s Media Innovation Center and leads the Center’s Knight-funded Innovators-in-Residence program. She is also the creative director and executive editor for the digital media startup 100 Days in Appalachia.[7] Reach her on Twitter at @poetabook.

Leave feedback on this sidebar.

- Steven Kotler, "The Acceleration of Acceleration: How The Future Is Arriving Far Faster Than Expected," Forbes, February 6, 2015, https://www.forbes.com/sites/stevenkotler/2015/02/06/the-acceleration-of-acceleration-how-the-future-is-arriving-far-faster-than-expected/#13f677ce3b18. ↵

- Ray Kurzweil, "The Law of Accelerating Returns," Kurzweil Accelerating Intelligence, March 7, 2001, http://www.kurzweilai.net/the-law-of-accelerating-returns. ↵

- Quartz, https://qz.com/. ↵

- "Make Every Week: Lunch Bot," Johnkeefe.net, http://johnkeefe.net/make-every-week-lunch-bot. ↵

- Matt Waite, ”How Sensor Journalism Can Help Us Create Data & Improve Our Storytelling,” Poynter, April 17, 2013, https://www.poynter.org/2013/how-sensor-journalism-can-help-us-create-data-improve-our-storytelling/210558/. ↵

- "Make Every Week Begets a Book," Johnkeefe.net, http://johnkeefe.net/make-every-week-lunch-bot. ↵

- 100 Days in Appalachia, http://www.100daysinappalachia.com/. ↵