30 Pitching Ideas

Mark Poepsel

To pitch a journalism or media product is to make the case for your idea to an individual or group in exchange for financial or some other kind of support. Pitching is a dynamic process that requires you to be of two minds. On the one hand, you need to believe in the value of your idea and in your team’s ability to make it viable. On the other hand, you must also demonstrate a capacity for change and perseverance as your idea evolves over time in response to feedback from potential customers and investors. Your pitch must demonstrate that you have a great product idea, that you have done market and competition research, and that you are willing and able to scrap key features, even ones you love, if feedback from customers or investors makes it necessary. Developing a pitch is more than coming up with a great idea for a media product and shopping it around to investors. It involves ideation, key feature identification and testing, market research, design and branding work, redesign, and pitch performance practice. At the heart of the pitch is your promise to develop a successful product, even though you may not yet know all of the variables that will influence its success.

Let’s freeze the conversation for a second for students who are not necessarily interested in being entrepreneurs. “Why should we study ideation, research, project management, and pitching?” You should study this because every job involves pitching. Journalists make story pitches every day and to a growing extent they are expected to provide evidence of engagement on previous similar stories to justify their pitch. For example, they may need to pull data from CrowdTangle or Chartbeat to show that stories about a particular bridge under construction garner a lot of attention and engagement. Stories may not seem sexy at first, but engagement numbers can help a journalist close the deal.

If nothing else, you will need to pitch yourself and your skills on the job market. If you treat your career search as a product to be managed, you will ideate potential outcomes in terms of workplace, location, and job description. You will go into job interviews with a well-researched plan, good-looking supplementary materials including your resume website, and you will know what the competition looks like. You need to understand what your “key features” are as a potential employee. You can refine those and present them well and find a good market fit for the product, i.e. your professional labor.

Studying how to ideate and to pitch is also fun. It’s not a lecture series or a knowledge dump. It’s a guided tour through a process of self discovery, group relationship building, and global market awareness. Even if you never take your own new endeavor to market, learning how to ideate and to pitch could and should change your life.

Pitching can happen formally or informally. An elevator pitch, a short two- or three-sentence description of your idea, is a pitch format you might use to describe your project to a stranger in casual conversation or to a potential team member at a meetup. It is similar to the log line in a film project. This chapter is designed for students who are developing formal pitches for ideas seeking seed funding. For best results, you should already be acquainted with the lean startup model of product development prior to creating your pitch. Developed by Eric Ries,[1] The Lean Startup stresses the value of customer development as its central thesis. In essence, the book states that the business of lean startups is to learn. You learn by practicing a sort of customer service science. Lean startup teams hypothesize about what product changes might work, and they test those changes on real consumers, a.k.a. users, so that the product is always improving, always moving closer to perfect product market fit. It’s an ideal that’s not often attained, but that’s the goal, and you need to be able to explain that you understand this concept and can put it into practice.

You may have begun (for real or in mock exercises) by self-funding the development of a prototype, a.k.a. bootstrapping, and you should have continued through the “friends and family” stage of financing where you have sought funding via personal networks, i.e. your parents, friends, perhaps a rich uncle.

This chapter assumes you have worked through the ideation phase of product development (see chapter on Ideation) and that you’ll continue to make improvements to your product even as you work on your pitch. Your team demonstrates leadership and change management skills by showing how your product has already evolved in response to customer development efforts. Customer development includes doing essential market research, testing features, and gathering and analyzing design feedback. The best pitches impart these nuts-and-bolts elements by demonstrating that your team has learned from this feedback and also convey the team’s passion, ingenuity, and perseverance. When your team has done as much product development and customer development as you can afford, or as time allows during a class session, you build toward a “big ask,” which may be a meeting with investors, a presentation to a startup competition committee, or a pitch contest, etc. This chapter focuses on preparing you for that big presentation, but it also briefly covers preparing an elevator pitch and writing a prospectus paper.

To narrow the scope of the discussion, this chapter identifies six presentation elements that serve as a starting point for pitch preparation. They are:

- Element 1: Brand identity image and tagline

- Element 2: Problem-solution narrative

- Element 3: Key features and your value proposition

- Element 4: Product-market fit description

- Element 5: Competitive analysis

- Element 6: Financial projections

These are the must-haves for a pitch about ten to fifteen minutes long. Each may be represented by one or more slides if you are crafting a slide deck or by one or more sections if you are writing a prospectus. Depending on your product, presentation type, preferences, and priorities, you should feel free to customize around this framework.

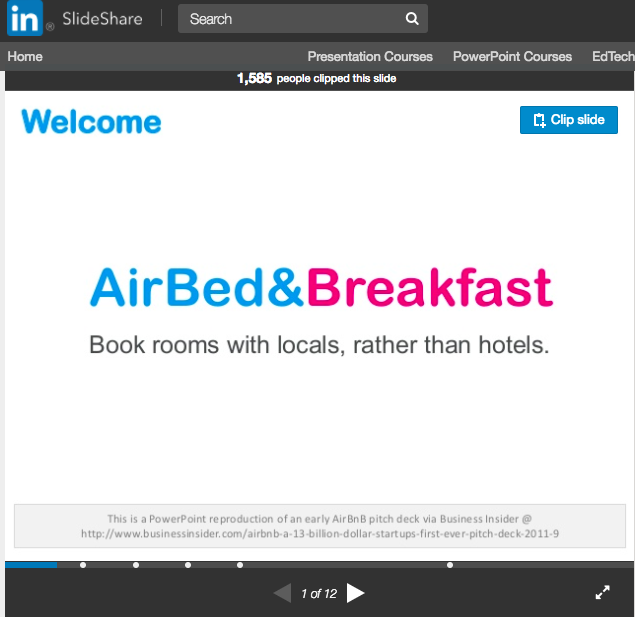

Slide 1: Airbnb started out as “AirBed&Breakfast.” Brand identity is established with a sans-serif typeface, use of color, and a clear tagline: “Book rooms with locals, rather than hotels.”Slide 2: The problem statement is straightforward: Travelers need an affordable alternative to hotels.

Slide 3: The solution statement focuses on the nature of the product, i.e. that it’s a web platform, and on key features and how they create value, both financial and cultural capital. Note that key features and the value proposition are already addressed through three simple slides.

Slide 4: To establish product-market fit, you first have to have a market. The Airbnb pitch deck notes that at the time there were 630,000 users on couchsurfing.com and that there were 17,000 temporary housing listings on Craigslist in San Francisco and New York combined in one week. Thus, there existed a large potential traveler pool and a large pool of people with rooms for lease, but these groups were in need of a unified platform.

Slide 5: The fifth slide details the size of the market and Airbnb’s share, showing potential for growth.

Slide 6: Completing the case for product-market fit, this slide shows the attractive user interface and provides a mini-narrative for how the product works.

Slide 7: This slide shows four years’ of revenue totals as simple math: 10 million + trips x $20 average fee = about $200 million in revenues. This is evidence of product-market fit and whets the investor’s appetite for potential future earnings.

Slide 8: This slide shows how Airbnb has already beaten its competition to own the market for certain events and to create partnerships.

Slide 9: Here, investors get the full picture of the competition.

Slide 10: The financial expectations are pretty well established by this point and were explained verbally. What this shows are the barriers to competition expected to help preserve Airbnb’s position and future earnings and growth expectations.

This chapter focuses first on developing the six presentation elements. When the time comes to build slide decks, the order, breakdown, and prioritization of elements is up to you. You are not expected to finish your product before developing your pitch. Rather, it is strongly suggested that you develop your pitch and your product in parallel.

PRESENTATION ELEMENT #1: Brand Identity Image and Tagline

Your presentation slide deck should begin with a memorable brand image. It can be a logo representing your product in a stylized way, or it could be a screen grab of your product if you are particularly happy with the design. It’s often a good idea to create a tagline as well. It helps drive the message home for investors who want to know right away if they see a marketable idea. From a persuasive standpoint, all you are trying to establish with your first slide is that this is a great product that many people need that’s easy to understand and remember.

Your brand introduction should be kept to one slide and should set the aesthetic tone for the rest of the presentation. Establish a color palette and stick with it. If you’re going to use design elements such as borders, background colors, or shapes, use them in your introductory slide. Go with clean, simple design elements. If something doesn’t add to your presentation, leave it out and keep it out in subsequent slides.

As you present the brand image and tagline visually, your talking points should include a brief description of the team. Don’t feel the need to introduce every member right away. The project manager should introduce the concept and herself or himself, and as the presentation moves on other members of the team can introduce themselves when it’s their turn to speak. There’s no correct way to divide up presentation responsibilities. Different courses and competitions will set requirements for the minimum and maximum number of speakers or group members you should have. Just be sure to keep the introduction slide focused and brief. Whenever it is your turn to speak, identify yourself. Mention your role and very briefly discuss your background as it pertains to your role on this project. Holding off on team introductions will keep your pitch moving.

You should start working on branding at the same time you begin product ideation. Establishing your brand identity is like selecting your best photo and description for a dating app. Put only your best face forward. Give investors a single, interesting, lasting image that they can connect to the rest of your pitch.

PRESENTATION ELEMENT #2: Problem-Solution Narrative

Every product solves a problem. Many entrepreneurial media products solve problems that users didn’t know they had. It’s your job to help the investor identify a media-related problem that many people share and then clearly explain in a story or short anecdote how your product solves the problem or, if it is not an outright solution, how it alleviates pain associated with the problem. Look at other problem-solution narratives in advertising and in corporate origin stories for examples of how to craft a quick, compelling problem-solution narrative.

Classic Problem-Solution Narratives

- A young man starting high school lacks muscle mass. He drinks milk and gets stronger, earning the respect of his classmates.

- Young people, pictured in silhouette, walk around a city looking bored with life. Then, they turn on their new MP3 players and start dancing in the streets. Their world is set ablaze in color and sound.

- A man literally turns into Joe Pesci when he gets hungry. He eats a candy bar and turns back into his normal self.

These may not be the greatest stories ever told. You’re not going to get a National Book Award for a Snickers commercial, but these are memorable narratives about people who have a problem that the product in question can solve.

You may want to personalize the narrative as it relates to you or someone on your team. This is common practice, but don’t force it. Often, student media entrepreneurs are caught in a quandary. They tend to come up with products suitable for their demographic that may not be massively appealing, or they come up with products for general audiences (read: people of a different generation). Then students may have difficulties crafting a relatable narrative. Your preference should be for creating a viable product and telling the product’s story as well as you can. Use your research and communication skills to craft narratives with a great problem-solution story. If your product is not for people like you, simply identify the type of person who has this problem or this pain point. Create user or customer personas (see Customer Discovery chapter[3]): “fictional, generalized representations of ideal customers.” Explain how your product is a feasible, meaningful solution for her or him. What motivates them to adopt your product? Tell the story in thirty seconds or less, in three slides or fewer.

By the time you create your pitch, you may have developed a concept and wireframe or some other mockup of a minimum viable product (MVP). Often the best way to present this narrative is to tell the problem-solution story verbally while simultaneously demonstrating on a couple of slides precisely where users need to tap or click to fix the problem. If this is a semester project for class, you may not have a prototype ready yet, but you should work to make your mockup look as much like the “real thing” as possible.

Try out different narratives on potential customers as part of your customer-development research. Keep internal records of which narratives work best. Ask people why these resonate more than others. You usually do NOT want to spend precious time delving into bullet points about key features at this stage. You can tell investors how the product works later on in the pitch. At this point you are simply a brand that solves a problem a lot of people have. Strive to make the narrative relatable and fun.

PRESENTATION ELEMENT #3: Key Features and Your Value Proposition

During your pitch, consider introducing investors to your key features, your value proposition and, where applicable, your user interface (UI) at the same time. Key features are the specific jobs your product or service accomplishes or assists with. A most basic example is that a bowl is innovative in relation to a plate. Both share the key feature that they hold food. A bowl adds another feature by holding liquids comfortably. Many innovative media products add several key features to solve nuanced problems. Limit yourself to developing a small handful of key features at first. Figure out how they will look and feel and be able to show users how your product’s design is easy to use.

One way to think of your value proposition is as the sum of your key features. How exactly are you solving problems, addressing pain points? The bigger the problem and the simpler the solution set, the more impressive your value proposition is likely to be.

At its core, a value proposition is a statement about why someone needs your product or service. How are you making their life better or making them more wealthy, with “wealth” being broadly defined?

Answer this question in your presentation visually while stating it verbally. Show investors your product or your UI and walk them through two or three tasks that can be accomplished easily. This is a chance to show off your key features and to make your potential investors understand your value proposition so well they become excited to invest and to bring this product with these, or similar, key features to audiences.

Demonstrate your UI or your product’s design in two or three slides. You may prefer to simply show a mock-up against a monochrome background so that the product’s design is all that investors notice. This will make the value proposition pop. Alternately, if you want the slides to carry over an existing set of design elements from the rest of your presentation, try to make the color palette, shape, and line selections for your slide background complement your product’s design elements.

Do not feel the need to introduce every feature or to narrate every design choice, but you should show that you have a good sense of design and that your design will make your key features easy to find and use.

A popular tool for creating wireframes is Balsamiq.[4] You can create mobile and/or web app wireframes that incorporate realistic design elements such as buttons, menus, and media players. You can build a wireframe mockup of your application or web application that users can actually click through and try out. If you work with a clickable wireframe, though, double and triple check that it functions properly on the device you will be using during your “big ask.” If you’re not completely sure that the functions will work, use a static mockup and sell it with your enthusiasm and with evidence of thoughtful, thorough research. If you are pitching a tangible media product, e.g. a wearable, you should bring a physical prototype for investors to try out.

Whatever your combination of digital mockup and tangible prototype is, it is preferable to show something basic that helps investors understand key features rather than show an elaborate mockup on which little or nothing works. Stick to the minimum viable product and keep the mockup clear and simple; however, note that certain startup competitions or investors may require working prototype sites or apps.

Tips for crafting great-looking, useful user interfaces are abundant online. They usually come with collections of colors in “color kits”[5] that serve as pre-determined palettes, and they will also include button and menu design styles for you to choose based on the tone and function of your product. Try out completely different approaches to UI on potential customers. Once you have narrowed down their basic color and design preferences using stock design elements, try creating your own color combinations, button styles, and menu designs. Stay within your users’ stated preferences, but apply your own creativity so that you can truly brand your product as your own.

I allude to the term “iterative development” throughout this chapter, but it merits definition here. Iteration in innovation refers to building out prototypes again and again–first for the developers themselves, then for beta testers, and then for a (hopefully) growing audience. At the root of the concept is repetition, which means the process of designing, building, testing, seeking feedback, re-designing, etc. continues indefinitely. Think, for example of a common platform such as Facebook and how many times it has been redesigned since you or the people you know have been using it.

If you spend even a few months using a favorite platform or app, you will likely see iterations of its development. What you need to know during the entrepreneurial pitch process is that iterating can happen while the pitch is being developed. This is normal and expected. You should seek to iterate based on user data and feedback. Iteration is not guesswork, and it’s not merely trial and error. It’s an informed repetitive development process meant to develop a product-market fit by molding the product to an existing market.

PRESENTATION ELEMENT #4: Product-Market Fit Description

In your team’s pitch so far, you have established a brand, demonstrated through storytelling how it solves a problem, and shown that your team is capable of designing an MVP with a combination of user input and your own creative design skills. You have shown investors that you and your team have a valuable idea and the skills to work in a lean startup environment using an iterative process. Now you must demonstrate how you are going to make money.

The next few slides in your deck should present a brief discussion of product-market fit. In two to three slides, show how big the market is, show where your product fits, and show evidence of iterative development according to customer preferences. Your goal is to quickly show the investors where there is an underserved mass market. Then, you must show that your product can tap that market and reach real customers. Every aspect of the market you are entering is fair game for questions from investors. You can head off killer questions by showing a depth of understanding about the market. There may be many solutions in the marketplace. Do not ignore them. Explain why your solution fits best. Explain that you’re working harder than anyone else to serve customers by directly testing their preferences.

Marc Andreessen of investment firm Andreessen-Horowitz calls product-market fit “the only thing that matters.”[6] Specifically, his commentary is about successful startups and whether team, product, or market matters more. He argues it’s the market. Andreessen says: “In a great market — a market with lots of real potential customers — the market pulls product out of the startup [original emphasis].”[7] None of your creative ideation or inspired design work matters if you can’t demonstrate knowledge of the marketplace. Practicing customer development, then, is establishing a process where you allow consumers to pull great products out of your efforts.

Fit your market research into your presentation in under a minute. Emphasize the size and strength of the potential market in a slide. Then, demonstrate that you have conducted careful customer research to learn what potential users want. You should have data from testing general product ideas, key feature combinations, and design elements. You should be able to show quantitative data, probably from surveys, and qualitative data, probably from focus groups. Present the highlights of customer development in a couple of slides.

Investors only want the summary of this data. Present it in a narrative form. For example: “We have found that our users prefer our social media app because their friends are using it, and as the number of friends using our app increases a certain amount, the amount users spend with the app increases in correlation.” If you’re not able to show that level of correlation in your data, at least be able to show that you are building the most popular version of your idea with key features that users preferred over all other potential features they were shown.

The visuals you use are up to you, but you must establish that there is a market for this kind of product and that you’ve sought to achieve product-market fit by developing a product with direct user feedback. That’s what customer development is all about. For the lean startup, it cannot be stressed enough how important customer development is. It’s not enough to show that you have had some good ideas. You need to show that you can bring your product and its customers together. Products evolve, and so do customer tastes, so you need to show that your team can already work on this product in response to user feedback data.

Market Research

Your first task in conducting market research is to define the scope of the media market where your product will compete. If you are working on a journalism startup, define a news niche in terms of geography and topic. If your news product focuses primarily on one topic, you will probably need to cover a wide geographical area, perhaps a national market.

If you are planning to bring news to a geographical region, limit it in a logical way. You might determine a reasonable driving radius around your community and cover the counties and cities within, which is essentially what defines a Designated Market Area (DMA) in broadcast news. You might wish to focus more narrowly on a single metro area or suburb.

Use census data to learn everything you can about the people who live in your coverage area. Read broadly about the history of the area, its economic background, and its economic future. Plug into the local entrepreneur scene long before you launch your media startup because understanding the startup market is your key to understanding the economic future of your area.

Most mass media startups that do not focus on journalism serve as communication platforms, games, or information curation/aggregation services. Service-logistics apps of the so-called “sharing economy” help people providing specific services to coordinate with others who need those services. If your team is pitching this type of app, avoid calling your product the “Uber of” something. Uber has become synonymous with corroded corporate culture,[8] and it has proven to be a high-stakes global gamble for investors. The sharing economy model is a difficult sell because the ideas are cheap and execution is expensive. Whatever your product is, you will need to demonstrate that this particular shared service is needed. You can’t expect to rely on sharing economy research in another sector to justify your concept. Nobody needs the “Uber of toothbrushes,” or do they?[9]

PRESENTATION ELEMENT #5: Competitive Analysis

After working through the first four presentation elements, students sometimes think that their product’s value is self-evident based on its key features, its design, and the strength of the marketplace. There is a tendency to think that because the processes of designing a product and strategizing about customer development are labor intensive those elements should be enough to demonstrate a product’s value, but investors will look for something more. They will want to know that your media product is not already available elsewhere, offered by someone with more experience and an established customer base. You must demonstrate that your product is unique.

Describe your competition as clearly and directly as possible. Name names. Cite links. Clearly and accurately describe their relevant products and their features. Describe in some detail what they do and don’t do. Know your competitors as well as you know your own brand. In the context of where your targeted markets overlap, know them better than they know themselves. Show that you have looked at trade industry publications detailing your competition’s strategies. Show that you have read, synthesized, and summarized up-to-date industry blogs’ take on your competition, and, most important, show that you understand your competitors’ strategy based on their About Page and design blog, if they have one.

Competitive analysis should be presented in about two slides. Pretending not to notice major players in the field will get you laughed off the presentation stage. You need to note in one slide who your key competitors are in the marketplace. You need to explain how your product or service is unique. What key features do you offer that no one else does? When you have similar features, how do you prioritize them or present them in ways that are unique or more affordable or more tailored to a target audience than the options that already exist? Answer these questions for each competitor.

Demonstrate this knowledge in clean, carefully crafted slides with straightforward storytelling. Neither overestimate nor underestimate the competition. When organizing this section of your slide deck, you are going to have to make executive decisions about what to leave in the presentation and what to cut. Use the “iceberg principle.” Present about one-tenth of the research you have done and be prepared to tailor the competitive analysis of your presentation for each investor or competition keeping in mind that competitors and markets are in flux.

Keep the pace quick and have a strategic counter for beating or at least competing with competitors’ strategies. It’s not enough to list their related products and the key features of those products. Identify the brand strategies so that you can anticipate where your competition is headed. You should be able to answer what you would do if someone new entered the marketplace doing the same thing you’re doing. Explain if this can be prevented. If it can’t, explain with substance how you’re performing better than the competition at delivering a similar product. If that is not possible, you need to come up with a different product. Pivot to target a different market or develop a different feature set. It’s essential that you don’t try to pitch a product that’s already available in the same marketplace (potentially from multiple sellers with more resources and experience).

You can present your competitive analysis by going through one competitor at a time and explaining how you will beat each one, or you can go topic by topic, such as “feature set,” “target market,” “user interface,” “supply chain,” “development costs,” “outcomes,” “branding,” etc. and explain how you will best your competitors on each item. This element of your presentation can easily get convoluted. You may not wish to address all of these elements. If you do good customer development work, you can prioritize which of these aspects of the product matter most to them and limit your competitive analysis discussion based on that research. In this way, customer development is doubly important. It tells you how to focus your own product and tells you where to focus your competitive efforts.

Your competitive analysis needs to evolve as you go through the customer development process. Each time you add or remove a key feature from your product, you must research who else is doing something similar and alter or amend your presentation to show that you’re aware of them and have a plan to beat them.

PRESENTATION ELEMENT #6: Financial Projections

In about three slides, explain your revenue model, that is, what your customers, advertisers, underwriters, etc., will be paying and what will they be paying for, as well as the costs to deliver those products or services. One of the best ways to express your revenue model is to work with the Business Model Canvas (BMC) (see Business Models chapter for more on this)[10] to map out how money will flow through your organization. The BMC helps you to picture how your startup fits into its financial ecosystem. It enables or forces you to think about who you’re going to work with and how you’re going to work with them to get the resources you need to provide valuable products or services. It helps you to plan to whom exactly you will deliver those services and how you will deliver them, and it demands that you understand what your costs are and where your revenue will really come from. The BMC will inform your estimation of startup costs and operating costs. From those (revenues, startup costs, and operating costs), you can determine your breakeven analysis according to what your class syllabus or competition guidelines require. Groups in media entrepreneurship classes often go through a dozen business model canvas drafts, or more, as they plan and develop their product and as they conduct customer development. The BMC will help you to decide on a revenue model and express it in visual form, though the actual visualization should be tailored to suit your product.

You must indicate how much of your startup funds you have already contributed, if you plan on seeking other funding sources, and what proportion of the business you are going to hand over to investors for the amount of funding you request. You should probably share only a summary of your plan. Spend no more than three minutes presenting realistic, well-thought-out financial estimates. Again, the iceberg approach may be the best approach.

Investors will want to know what basis you have for your financial estimates and claims. Often, this is the part of the presentation that generates the most questions from the audience. Document your sources for any financial assertions you make and be prepared to hand over more detailed business plans if asked. Make the case that your product is a great investment. Practice with mentors, friends, family members, and your professors so that you can make the strongest possible feasible case for funding.

Pitch Deck Examples

An example of a successful pitch is CardLife featured on this[11] blog post of the 35 best pitch deck examples. It is a tracking company that communicates to users, usually business, how much they are spending on subscription software services. Businesses have a problem. They subscribe to many software solutions. They do so at different times for different amounts for plans that may renew automatically year over year or that may increase in price, sometimes without review. CardLife helps track this expense in order to make it easier for businesses to balance budgets. This is a business that serves other businesses, yes, but it’s also media-related because it gathers, tracks and presents information in a service that’s designed to be easy to use. It’s a time saver and potentially a stress reducer. The slide deck established that this is a problem for businesses by keying in on one number: 93%. That’s the percentage of businesses that fail to keep track of their software and other subscription expenses. In their pitch, they note that 1,000 businesses signed up for their service within six weeks of launch, and they note that they are connecting to a $10 billion industry. Though they cannot plan on receiving a portion of that particular pie, by being connected to such a large market with continued growth potential, they easily make the case that their business is positioned for future growth. Please review their presentation video and slide deck. It’s No. 15 on this list, which includes several other examples of solid slide decks accompanied by videos of each as they were given by the entrepreneurs themselves at Y Combinator 2017.[12]

Mobile Development Costs

Let’s start with an anecdote: In our entrepreneurial media management course at Southern Illinois University in Edwardsville, guest judges came one semester and quoted wildly different costs for app development. One estimate was based on an alert app that let students know when on-campus athletic events are being held. Students budgeted tens of thousands of dollars in their plan to build a fully functional app, but the guest judge said he had proposals for similar alert services on his desk that would cost the university about $2,000.

At a pitch competition later the same semester, a different team proposed to a different set of judges to build a new social media platform that would visualize posts and group audiences into “cliques” enabling social media managers to send targeted message to only certain “cliques,” in real time. One judge happened to have served as an adviser to a military contractor who wanted to develop its own social media platform. He had a front-row seat to the proposal, and his company quoted a base price (with a development team of dozens of software developers) at $20 million. Thus, the class was left with a range of costs for “app development” somewhere between $2,000 and $20 million. The best way to estimate costs for an app is to look for something with a similar feature set and find out how much seed money it got in its earliest round or rounds of funding.

FOLLOW UP

Question and Answer Preparation

Preparing for question and answer sessions with potential investors is something of a challenge because every investor is different. You should anticipate likely questions and be prepared for “wild card” questions by having an open mind and by practicing your pitch in front of different audiences. Vary the age of your pitch audience. Get test audiences that vary in income level and education. Sometimes you are not pitching to the investor but to the investor’s idea of who the consumer for this product must be. Once you have practiced presenting in front of various audiences, you should identify a few likely questions and prepare well-researched answers. You need not promise the world to an investor. But you must be prepared to indicate your plans for improvement, or be able to explain why something that seems like it should be done is not yet done. You should identify known weaknesses in your pitch and prepare reasonable answers regarding your plans to improve upon shortcomings. You may plan to conduct further research where more information is needed, or you may have identified key features that need to be altered or replaced. If you have identified something that needs doing and that isn’t done yet, that may not be a deal breaker as long as you have a reasonable plan for making changes and you show that you are prepared for change.

Staying Connected

You should also strategize for staying in touch with any potential investors. Task a point person with collecting and organizing investors’ contact information. Make note of each investor’s investing background and interests and take detailed and careful notes about their feedback regarding your pitch. Do your research. You should know any potential investor’s history and strengths and weaknesses. Treat an investor’s individual concerns as the most important keys to your success. Making it work with one real investor ready to cut a check is more important than developing a perfect product pitch for future potential investors.

Generally, cold calls to angel investors are not appreciated. Work carefully immediately after an investor expresses interest in your proposal to open a line of communication. Follow the investor’s preference, which may be for asynchronous communication such as email or SMS, or they may prefer to speak via video chat or by phone.

One goal, perhaps the goal of an initial pitch is to gain enough interest on the part of an investor that she or he wants to hear a second, personalized pitch in the near future.

You are not going to meet your “soulmate” investor the first time out or in any of the first ten times making your pitch. Shoot for a 1 in 100 rate of success at setting up a meeting with a funder. That means that for every 100 contacts you make, one of them might consider funding your business.

There is often a two-step flow to reach an investor. You may need to pitch a surrogate who can get you a meeting with the right investor. As a baseline, you, as a representative of your startup, ought to have an up-to-date LinkedIn profile. You should have a professional Twitter account where you follow and connect with investor networks, and you should plan on attending events with investors and other entrepreneurs through Eventbrite and Meetup.

Show up early to events. Stay late. Strategically attend paid events where investors are the invited speaker for a better shot at meeting the right investor. The “right” investor is the one who shoots you down but who knows three or four other investors who are more likely to be interested in your idea or your brand.

Be where other startups are, such as co-working spaces, and consider creating a recruiting profile for your startup on AngelList. You need to be easy to find and ready to meet.[13]

If you make your pitch informally 100 times, you will have the opportunity to refine your idea and your informal narrative. You will learn what gets investors excited, how to pace your informal pitch, and you will learn to move away from all-or-nothing formal pitches on the stage to the kinds of informal conversations with connected people who can get you a meeting with the right investor. It is important to learn who the connectors are, who are “all hat and no cattle,” and ultimately you must know what you are asking for: a sit-down meeting with an angel investor who will listen to your idea.

The informal pitch may include a ballpark figure funding goal, but above all else should communicate capability and passion for the idea.

Your first pitch to an investor, according to the odds, will not result in an offer of funding.

The investor will often tell you why she or he is interested in your pitch. Keep this in mind and ask if there are any portions of the pitch that they would like to know more about. Be straightforward and be open to change. Know when to stop selling and listen. Know that you need not point out any flaws in your product when discussing a possible investment. A solid, experienced investor will have noted many or all of the potential flaws, conflicts, and stress points in your product pitch by researching your business before the meet.

Gauging investor interest is important. It is subjective. It takes time and regular, professional communication. You can change mockups and make prototypes with investor input in mind, but you must consider your costs and recognize when an investor is not serious. You do not want to spend more than your startup can afford to alter your product for an investor who is only testing the waters.

How often you communicate with a potential investor depends on their availability, their willingness to communicate, and how many resources you have at your disposal for cultivating relationships. One thing is for sure: You must follow up with potential investors. They will expect you to do so if they have expressed an interest in your proposal.

A few somewhat universal goals you might pursue for communicating with interested investors:

- Establish a pattern of regular communication.

- Encourage the investor to use your prototype.

- Encourage her or him to ask questions and make suggestions.

- Expect to pitch to a potential investor again and again. Expect to make follow-up pitches and progress reports consistently and professionally regularly even after she or he has bought in.

- As you work to secure and reassure investors, your work will likely evolve to include two difficult but essential facets: 1. You will have to be the communicative connector between your customers and investors. 2. You will need to keep innovating even after investors have thrown their weight around.

OTHER TYPES OF PITCH

There are a few other types of pitch you may wish to prepare or that you may be assigned to develop besides the somewhat standard ten- to fifteen-minute slide deck proposal. The following are examples of longer-form and more brief pitch types: elevator pitches, three-minute pitches, prospectus writing, and nonprofit pitches.

Elevator Pitches

The elevator pitch, or Twitter pitch, should land somewhere between a branding statement and a problem-solution narrative. It should take no longer than a minute to deliver, and in most cases it ought to be memorized. The point of an elevator pitch is to earn a chance to make a longer pitch at a later date at the time and place of the investor’s choosing. Giving an elevator pitch is an art. It’s often done informally at networking events. In movies, these types of pitches are given in bathrooms, on the street, in the firm’s lobby as a courtesy, or, yes, in elevators. In reality, you never know when you might need to give an elevator speech. That’s why you always have it memorized.

Be able to tell a potential investor precisely what your product does, why a mass audience would be interested, and where mass revenues are going to come from. All other aspects of the pitch will be in response to questions—if you can manage to get an investor interested. If you’re asked to write one, make it two to three sentences, or a tweet. Write one that’s easy to memorize so that any member of your team can deliver it and any potential investor can comprehend what the brand is, what you do, and how you plan to make money.

Three-Minute Pitches

Two- or three-minute pitches are often used at “pitch days” or “speed dating” events where many entrepreneurs and many potential investors or well-connected people meet to hear what’s being developed. Rather than tailoring a deck for a potential investor or for a competition and then reading the audience during the pitch performance, you may need to take a Swiss Army Knife approach and develop a handful of different short, completely scripted pitches to present to different people depending on their role (e.g. investor or journalist), their field (e.g. tech, advocacy, PR), or their attention span.

When startups attend pitch days in front of prospective investors, there is a formulaic approach to the ask. While you may not need to adhere to a script for a slide deck, a solid three-minute pitch can help you attract vendors and suppliers, woo landlords and advertisers, recruit employees, and win over other advocates. And, yes, maybe even investors someday (at which point you’ll revisit that pitch deck).[14]

Craft pitches that are long enough to incorporate a narrative without missing the essentials of the elevator pitch. Joanne Cleaver, writing for Entrepreneur.com, suggests that the three-minute pitch can be tailored to an audience according to this formula: “Get their attention, tell them the right story, and keep ‘em on the hook.”

Prospectus Writing

A successful pitch presentation might end with an investor asking for your prospectus. “Prospectus” is a tricky term in the startup world. Prospectus.com spells out all of its potential meanings:

“A prospectus is somewhat used as an interchangeable term. Often a business plan is referred to as a prospectus, as is the private placement memorandum (PPM). In many cases, the prospectus is a public disclosure document that, like the PPM, is used to disclose the company’s data prior to a public listing of securities (with the goal in mind to raise capital publicly). However, prospectuses are also used in the private placement market and often the term itself is employed in lieu of an offering memorandum or a PPM. Referring to your business plan or your private placement memorandum as a ‘prospectus’ is not inaccurate, but it may not be precise [edited for spelling and clarity].”[15]

Be sure you know what’s being asked of you if someone asks for a “prospectus.” Have your complete business plan ready in case that’s what an investor really wants to see. It’s much more feasible to break down a business plan into different types of prospectuses depending on who’s making the request than it is to try to turn a legal prospectus into a complete business plan.

“Whether you are raising private capital or set to launch a publicly listed company on a stock exchange, a business plan and a disclosure document is required.”[16] Per prospectus.com, the document needs at a minimum the following information:

- Terms of the Offering: The terms should be directed to a targeted audience of appropriate investors.

- Regulation Disclosures: Whatever regulations exist for raising funds need to be indicated and addressed.

- Management Team: Describe who is leading this organization, what each person’s background is, and where they are getting their help from in terms of outside organizational or institutional support.

- Risk Factors: In particular, note any risks associated with the specific field you are trying to enter.

- Subscription Procedures: You need to write up a legal document to explain the terms of the stock or other security your startup is offering.[17]

For this text, a prospectus refers to a summary of a business plan put in writing that might be used as a disclosure document. There are online aids available that can help you write a business plan, which can be streamlined and used as a prospectus. You should make contact with a lawyer before you make any serious pitches to investors. The best advice may be to use the U.S. Small Business Administration’s tools for crafting a business plan as completely as you can, and then based on a thorough examination of the marketplace and your plans, you can then craft a prospectus.

Nonprofit Pitches

Nonprofit startups need to make pitches to request funds, and they may still go through the process of bootstrapping, asking friends and family for money, and eventually going to larger investors (i.e. donors, foundations, grantors, etc.) to try to get their business off the ground. In the vast majority of cases, nonprofit organizations will need to identify various revenue sources apart from the initial grantor or foundation if they plan to stay afloat. Thus, nonprofits often have to be grant-managing machines and great pitch developers too. Other ways that nonprofits bring in revenues beyond getting grants include signing up small donors in person at community events, hosting fundraising galas, crowdfunding, making direct mail requests, and sending phone, email, and text requests.

Potential sources of revenue must be described in great detail in any documentation explaining your nonprofit business plan. Other elements should still be included: branding, a problem-solution narrative, communications plans and tools demonstrating your design sense, an analysis of the “competition,” and financial plans. They need to be addressed in terms of terminology and tone to donors and grantors, but at the end of the day the pitch for a nonprofit business has a lot in common with a startup pitch.

TOOLS TO IMPROVE YOUR PLAN AND YOUR PITCH

The Business Model Canvas mentioned earlier can be used to develop the components of your pitch; however, it shouldn’t be used as a checklist. The sections of the canvas flow into one another and should be considered a strategic whole.[18] Write and edit multiple versions of your business model so that you could make it into a flipbook and animate it if you wanted to.

If your company or university would pay for it, Strategyzer costs $299 per year and allows you to electronically build within the BMC framework and to generate reports based on what you have proposed.[19] The Value Proposition Design text zeroes in on two points of the BMC—the value propositions and customer segments—and breaks down your analysis and development into smaller units that can be profiled, anticipated, and measured to try to achieve the best product market fit as you further develop your actual product and test it with users.[20]

Canvanizer[21] and BMFiddle[22] allow you to digitally build the BMC over and over again. With some practice, either can be a useful tool for applying virtual sticky notes to the BMC. Neither does your thinking for you, but if you’re looking for inspiration, BMFiddle shares the Skype BMC example.[23]

Regardless of the tool you use, it is essential not to be boring. Present your slide deck to new people consistently. Present it to people with no knowledge of investing or entrepreneurial pitches to see how they respond to the design and the flow of your presentation.

Guy Kawasaki offers good guidelines for using PowerPoint in his 10/20/30 rule.[24] You may have to adjust your presentations for each pitch setting, but these are solid guidelines to start with. Kawasaki says that a slide deck should have 10 slides, the presentation should take about 20 minutes, and the type size should be at least 30-point. Follow these rules to have easily understood PowerPoint presentations that don’t drone on and that conform to investors’ expectations when dealing with startups. The 10-slide structure presented by Kawasaki is a good alternative to the structure presented in this chapter.

PITCHING PRACTICES — WHAT RESEARCH SAYS

Scholars study the art and (social) science of the startup pitch. The discussion here includes brief analyses of research on the use of rhetoric in pitches, the role gender plays in pitch success, and analysis of how entrepreneurs can dress to win. Useful academic research focusing narrowly on entrepreneurial pitches has been done, but the body of pitch research is not nearly as robust as work delving into other aspects of entrepreneurial business management and success.

Plenty of articles have been written about how to pitch. Some may prove useful to you in planning and delivering your pitches, but they usually lack academic rigor. This section is a synthesis of carefully conducted social science research that has gone through peer review. Assumptions were tested. Findings are backed by detailed evidence, and limitations are acknowledged directly in detail.

Successful Presentation Language: Framing the Pitch

Research regarding rhetoric in pitch presentations covers a variety of areas. This is an interesting area of study for scholars of rhetoric because pitch competitions and television shows are fertile ground for looking at what works in contemporary persuasive speech. One key concept is “impression management.”[25] In a recent publication in the Journal of Business Venturing, Parhankangas and Ehrlich examine down to the word “How entrepreneurs seduce business angels.” They looked at what words or types of words helped entrepreneurs actually secure funding and found that there may be optimal points in terms of numbers of words to put in your pitch deck for employing “positive language” (nine words), for self-promotion regarding your ability to innovate (2.8 words), for referencing your own weaknesses (3.5 words), and for “blasting” the competition (3.3 words). This serves as a reminder that these things – referencing your innovativeness, your weaknesses and your competition’s failings – are good to do in a pitch, but you probably shouldn’t overdo it. There seems to be, at least based on one study, a “Goldilocks”[26] point beyond which you don’t want to step.

Stay positive, and reference your skills and failings and your competition’s major weaknesses without overdoing it. Another paper on rhetoric and the entrepreneurial pitch looks at how Korean entrepreneurs reconfigured their pitch decks when participating in a competition designed to bring already successful Korean products to American markets. The entrepreneurship program studied here is intense. Program organizers and their staff do “actual market research for each company’s product, and the competition’s winners receive actual business development that has historically led to actual deals.”[27] The authors of this paper probably use the word “actual” so often because they want to stress that this is not a paper about “merely academic” concepts.

They analyzed initial pitch decks and final decks of fourteen teams that completed the program: “a full cycle of activity: application to the program, initial pitches, initial feedback from program personnel, detailed feedback from representative stakeholders in the target market, and revised pitches.” Product claims changed as teams went through the program: “There is a change in wording or details to provide more evidence-based and benefit-oriented language.” At times, questions raised in the feedback process were directly addressed in rebuttal slides showing an engagement in the process that reached beyond trying to perfect the pitch deck. When entrepreneurial pitch development programs are running at top speed, so to speak, entrepreneurs show they can think strategically about their product, their market, and how to communicate to all types of audiences the value of their solution and their approach to solving problems.

Another article, published in IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, analyzed frames used by entrepreneurs and how they are developed.[28] Here, “frame” is a way of talking about something that helps connect your understanding of an object, product, or event with other people’s understanding and values. The article states, “The entrepreneur acquired the most influential frames through stakeholder discussion, applied these frames in a way that stacked and made salient multiple frames beyond the problem-solution frame, and judged frame fit by considering the degree to which catchers took up the frames.” The author calls investors and stakeholders in this study “catchers” to stress that they are the ones pitches are directed to. It’s important that they understand, so it can help to use multiple frames.

Problem-solution is just one frame you can use. What this means for students is that the way you describe your product will probably evolve as you talk about it with stakeholders, and it should probably evolve in ways that are meaningful to them. It’s okay to stack frames if you need to. You can work to come up with different, specific terms that help define your innovation in different contexts for different groups. The example in this paper framed the innovation – a nonprofit organization called Hacker Gals – as a collection of hackers who know about computers, makers who get things done, and women who have unique perspectives in the startup world. The combination of frames helped the paper’s author, who also runs the startup, to communicate better with more stakeholders. Ultimately, more specificity emerged as she reworked her pitches: “Specificity and salience appeared to be, in other words, directly proportional.” Thus, one thread tying all these rhetorical analyses together is that specificity is important in entrepreneurial pitches, but it doesn’t come only from the minds of the pitch team. It comes as a result of working and reworking the pitch with stakeholders and mentors.

Gender and Pitch Success

Lakshmi Balachandra, Anthony Briggs, Kimberly Eddleston, and Candida Brush studied how gender affects the way entrepreneurial pitches are perceived.[29] They did not find that being female absolutely precluded an entrepreneur from finding funding, but they did find that “gendered expectations do make a difference as women entrepreneurs who present masculine behaviors are more likely to be evaluated positively than those who do not.” The authors continue, “Interestingly we find women entrepreneurs have stronger communication skills, but rates of women’s entrepreneurial participation remain weaker than men’s.” The authors suggest that this is because investors, generally speaking, are males who prefer to see so-called “masculine behavior,” characterized as “bold,” “attentive,” “[demonstrating] self-assurance,” “calm,” and “confident,” in women giving entrepreneurial pitches.

The authors go on to say: “Consistent with liberal feminist theory, women do face bias in terms of the masculine stereotype held by the majority of the male-dominated investment community: During the pitch, women should ‘act’ like men and indicate masculine behaviors or they may be penalized by investor audiences to not have the qualities they believe to be consistent with entrepreneurship.”[30]

Students shouldn’t interpret this article simply as a plea to female entrepreneurs to “Pitch Like a Man” in early-stage pitch presentations, to reference the title of this article. Social structures setting the norms for pitch analysis need to change. Investors must become aware of their own biases and retrain themselves to analyze pitches on their own merits rather than on the gender of the people making the pitch. Scholars and advocates are better positioned to demand these changes than entrepreneurs begging for startup funds in an environment where the success rate is very low.

What to Wear

The quality of a pitch presentation is subjective. Investors and judges will notice when a pitch lacks quality, but they might not care to or be able to discern if it was the style of dress or style of presentation that spoiled the deal. Your dress and your performance can obviously influence whether or not your pitch is successful, but there are not many hard and fast rules. Web resources are filled with advice on how to dress and whether or not you should wear formal business attire, business-casual attire, or even casual attire. What’s essential is that you research what pitch competition calls for or what the investor prefers. Just ask how formal the context of the presentation is and dress accordingly. If it’s a competition, look for media from previous events showing how previous winners were dressed.

There’s not a deep pool of academic research on what to wear to your pitch presentation, but scholars have shared a clear idea of what doesn’t work: “Casual dress and nonchalance have a negative influence on investors’ evaluations.”[31] Do the research that allows you to dress to suit the occasion. When in doubt, wear a business suit and jacket. You can always set the jacket aside and lose the tie or your most formal accessories, e.g. Mom’s pearls, if needed.

The Importance of Performance

There is a better body of work on performance and what works. Jeffrey Pollack, Matthew Rutherford, and Brian Nagy reviewed 113 successful pitches from the TV shows Shark Tank and Dragons’ Den (Canada’s answer to Shark Tank).[32]

They had students rate these successful pitches and noted that those who were more prepared received more funding, and they found that perceptions of legitimacy had to be present for this relationship to work. This suggests that merely being over-prepared isn’t enough to secure the most funding. An entrepreneur must be prepared and legitimate to survive the sharks. What comprises legitimacy? In this study, it was a wide variety of concepts ranging from the founder’s level of experience to the business’ likelihood of gaining good media attention. Additionally, showing strong management skills, existing resources, and likelihood of gaining endorsements helped.

Digging Deep Into Performance Types and Practices

Even if investors don’t want to acknowledge it, the quality of the pitch makes a difference. Studies show that investors often say their decisions are based on rational elements of the business and the plan presented to them. However, an article titled “The Impact of Entrepreneurs’ Oral ‘Pitch’ Presentation Skills on Business Angels’ Initial Screening Investment Decisions” suggests otherwise:

“Presentational factors (relating to the entrepreneurs’ style of delivery, etc.) tended to have the highest influence on the overall score an entrepreneur received as well as on business angels’ level of investment interest. However, the business angels appeared to be unaware of (or were reluctant to acknowledge) the influence presentational factors had on their investment-related decisions: the stated reasons for their post-presentation intentions were focused firmly on substance-oriented non-presentational criteria (company, market, product, funding/finance issues, etc.).”[33]

How do you show preparedness? Melissa Cardon, Cheryl Mitteness, and Richard Sudek suggest that it’s essential the pitch team demonstrates that it understands the larger context of the market and social conditions for their product. “Not surprisingly, our results confirm that entrepreneurs seeking funding from angel investors need to have a strong opportunity and be perceived as competent. More important, beyond these factors, entrepreneurs appear to be able to increase their chances of receiving funding if they are able to signal to potential investors that they are prepared, meaning they have thought through the big picture and impact of their product or service and are able to answer questions with confidence and without appearing defensive.”[34]

This suggests that for your pitch performance to land, you need to demonstrate not just that you understand how your business model works but that you understand how all similar business models work, what the economic conditions in the related field need to be, and whether those conditions are present.

The research of Sean Williams, Gisela Ammetller, Inma Rodríguez-Ardura, and Xiaoli Li finds (based on a study of a small sample) that different cultural values are evident in the entrepreneurial pitches made in different countries.[35] Even if you’re not presenting outside of your most comfortable cultural sphere, it may be in your best interests to learn about the values of the organization, angel or judges you’ll be pitching to and speak to those values to maximize your success. These scholars considered entrepreneurial values in pairs, e.g. some entrepreneurs tend to focus on the motivation of profits while others focused more on autonomy. Some tend to promote individualism while others show the strength of their networks. Some focus on learning while everyone (in this small study) discussed action. The country-by-country breakdown in this study’s results is somewhat murky, but these pairings ought to be helpful for you to consider what kind of entrepreneur you are. Identify your values and communicate them. Look for investors and competitions that are trying to achieve the same things with their entrepreneurial efforts.

PRESENTATION TOOLS

There is more to life than PowerPoint, but Prezi gives people headaches. If you must use PowerPoint, generate a branded deck format or, perhaps better yet, let the product design lead the way and have a plain deck background. Avoid extensive use of bullet points. Illustrate every number that appears in your presentation. A dollar amount belongs in context. You should either demonstrate expected growth or expenditures or represent your target market, for example, as a small piece of a relatively large mass media pie.

Alternatives to the traditional deck include Perspective by Pixxa, which allows you to represent and animate data, and Haiku Deck, which includes lots of propriety art elements and a startup pitch template — not for professionals but perhaps good for novices getting right to work. Slidebean is good for producing pitches and testing online because it has built-in support for analytics and tracking. Wideo, an animation development app, can be used to completely stack and time a deck with various animations within and between sides.

Spinuzzi, et al. developed another paper on pitch deck development and noted that in intensive pitch competitions entrepreneurs are quite limited in how they can adjust their decks. Consider yourself lucky if you can develop your product and your pitch at the same time so that feedback on your pitch is simultaneously feedback on your innovation. In the same article, authors identified three ways pitch decks are most often altered. The structure of the deck may change—slides can be added and deleted. The claims and evidence may be clarified or strengthened, and the level of audience engagement may be tweaked. Consider judging yourself on these three areas as a good, overarching, holistic approach to determining what, if anything, you can improve on as you work to perfect your pitch.

Resources

See Startup Funding: Why Funding[36] for resources on pitching.

Mark Poepsel, Ph.D., is an assistant professor at Southern Illinois University in Edwardsville in the Department of Mass Communications. He researches media sociology and leadership in journalism organizations and teaches courses in media management, media entrepreneurship, graduate research methods, broadcast writing, introductory writing, and introductory theory. In 2016, he was a fellow at the Scripps Howard Journalism Entrepreneurship Institute, and he was a Scripps Visiting Professor in Social Media. Reach him on Twitter at @markpoepsel.

Leave feedback on this chapter.

- Ries, Eric. The Lean Startup: How today's entrepreneurs use continuous innovation to create radically successful businesses. (New York: Crown Business, 2011). ↵

- "Airbnb First Pitch Deck," Pitch Deck Coach on Slideshare, https://www.slideshare.net/PitchDeckCoach/airbnb-first-pitch-deck-editable. ↵

- Ingrid Sturgis, "Customer Discovery," Media Innovation and Entrepreneurship, https://press.rebus.community/media-innovation-and-entrepreneurship/chapter/customer-discovery/. ↵

- Balsamiq, https://balsamiq.com/. ↵

- Alex Ivanovs, “Top 35 Free Mobile UI Kits for App Designers 2017,” colorlib, March 9, 2017, https://colorlib.com/wp/free-mobile-ui-kits-app-design/. ↵

- Marc Andreessen, “The PMARCA Guide to Startups. Part 4: The Only Thing That Matters,” Pmarchive, June 25, 2007, http://pmarchive.com/guide_to_startups_part4.html. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Mike Isaac, “Inside Uber’s Aggressive, Unrestrained Workplace Culture,” The New York Times, February 22, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/02/22/technology/uber-workplace-culture.html. ↵

- Julie Schott, “Is Quip the Uber of Toothbrushes?” Elle, August 7, 2015, http://www.elle.com/beauty/reviews/a29700/quip-toothbrush-subscription/. ↵

- Strategyzer, “Business Model Canvas Explained,” YouTube, September 1, 2011, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QoAOzMTLP5s. ↵

- "35 Best Pitch Decks That Investors Are Talking About," Konsus, https://www.konsus.com/blog/35-best-pitch-deck-examples-2017/. ↵

- "35 Best Pitch Decks From 2017 That Investors Are Talking About," Konsus, https://www.konsus.com/blog/35-best-pitch-deck-examples-2017/. ↵

- Hernan Jaramillo, "11 Hacks to Get Meetings With Investors in Silicon Valley,” HackerMoon, January 12, 2015, https://hackernoon.com/11-hacks-to-get-meetings-with-investors-in-silicon-valley-14b4851ab3e8. ↵

- Joanne Cleaver, “3 Steps to the Perfect 3-Minute Pitch,” Entrepreneur, March 20, 2015, https://www.entrepreneur.com/article/242523. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- “Business Plan vs. PPM vs. Prospectus,” Prospectus.com, https://www.prospectus.com/business-plan-vs-ppm-vs-prospectus/. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Alex Osterwalder, “Tools for Business Model Generation,” Stanford eCorner, February 2012, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8GIbCg8NpBw. ↵

- Strategyzer App, https://strategyzer.com/app. ↵

- "Value Proposition Design," Strategyzer, https://strategyzer.com/books/value-proposition-design. ↵

- Canvanizer, https://canvanizer.com/new/business-model-canvas. ↵

- Business Model Fiddle, https://bmfiddle.com/. ↵

- Example from Business Model Generation, BMFiddle, https://bmfiddle.com/f/#/local. ↵

- Guy Kawasaki, "The 10/20/30 Rule of PowerPoint," GuyKawasaki.com, https://guykawasaki.com/the_102030_rule/. ↵

- Annaleena Parhankangas and Michael Ehrlich. “How Entrepreneurs Seduce BusinessAngels: An Impression Management Approach.” Journal of Business Venturing. Vol. 29.4. July 2014. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2013.08.001. ↵

- "Goldilocks Principle," https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Goldilocks_principle. ↵

- Clay Spinuzzi, Scott Nelson, Keela S. Thomson, Francesca Lorenzini, Rosemary A. French, Gegory Pogue, Sidney D. Burback, Joel Momberger, “Making the Pitch: Examining Dialogue and Revisions in Entrepreneurs’ Pitch Decks.” IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication 57 no. 3, September 2014. http://hdl.handle.net/2152/25712. ↵

- Stacy J. Belinsky and Brian Gogan, “Throwing a Change-Up, Pitching a Strike: An Autoethnography of Frame Acquisition, Application, and Fit in a Pitch Delvelopment and Delivery Experience,” IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 59 no. 4. October 2016, http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/7592403/. ↵

- Lakshmi Balachandra, Anthony Briggs, Kimberly Eddleston, and Candida Brush, “Pitch Like a Man: Gender Stereotypes and Entrepreneur Pitch Success,” Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research, 33 no. 8, June 2013, http://digitalknowledge.babson.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2634&context=fer. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Louis F. Jourdan Jr., “The Relationship of Investor Decisions and Entrepreneurs’ Dispositional and Interpersonal Factors,” Entrepreneurial Executive, 17 no. 1, January 2012. ↵

- Jeffrey M. Pollack, Matthew W. Rutherford, and Brian G. Nagy, “Preparedness and Cognitive Legitimacy as Antecedents of New Venture Funding in Televised Business Pitches,” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice. 36 no. 5, September 2012, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/233733878_Preparedness_and_Cognitive_Legitimacy_as_ Antecedents_of_New_Venture_Funding_in_Televised_Business_Pitches. ↵

- Colin Clark, “The Impact of Entrepreneurs' Oral ‘Pitch’ Presentation Skills on Business Angels' Initial Screening Investment Decisions,” Venture Capital: An International Journal of Entrepreneurial Finance, 10 no. 3, July 2008. ↵

- Melissa S. Cardon, Cheryl Mitteness, and Richard Sudek, “Motivational Cues and Angel Investing: Interactions Among Enthusiasm, Preparedness, and Commitment.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, October 2016, http://www.effectuation.org/?research-papers=motivational-cues-angel-investing-interactions-among-enthusiasm-preparedness-commitment. ↵

- Sean D. Williams, Gisela Ammetller, Inma Rodríguez-Ardura and Xiaoli Li. “A Narrative Perspective on International Entrepreneurship: Comparing Stories From the United States, Spain, and China,” IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 59 no. 4, December 2016, http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/7736039/. ↵

- CJ Cornell, "Startup Funding: Why Funding?" Media Innovation and Entrepreneurship, https://press.rebus.community/media-innovation-and-entrepreneurship/chapter/section-2-why-funding/. ↵