1.3: The Communication Process

Learning Objectives

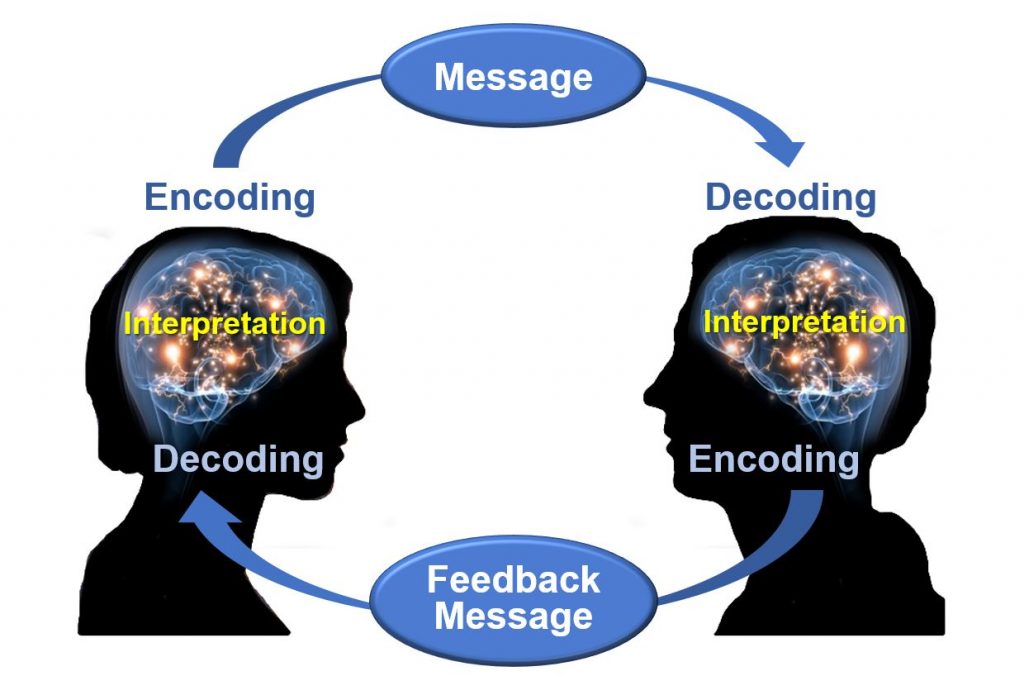

8. Illustrate the communication process to explain the end goal of communication

Stripping away the myriad technology and channels we use to communicate, at its core, the whole point of communication is to move an idea from your head into someone else’s so that they understand that idea the same way you do. If there is work to be done to ensure that the person receiving a message understands the sender’s intended meaning, the responsibility falls mainly on the sender. However, the receiver is also responsible for confirming their understanding of that message, making communication a dynamic, cyclical process.

Breaking down the communication cycle into its component parts is helpful in understanding your responsibilities as both a sender and receiver of communication, as well as troubleshooting communication problems. First, let’s appreciate how amazing it is that you can form an idea as an incredibly complicated pattern of electrical impulses in your brain and plant that same pattern of impulses in someone else’s brain very easily. It may sound complicated, but you are wired to do this every second of the day.

According to the Osgood-Schramm model of communication (1954), you first encode an idea into a message when you want to communicate that idea with the outside world (or even just to yourself). If you choose to send that message in the channel of in-person speech (as opposed to other spoken, written, or visual channels, examples of which are listed in Table 1), you first form the word into the language in which you will be understood, then send electrical impulses to your lungs to push air past your vocal cords, send electrical impulses to vibrate your vocal cords to bend the air into a sound, shape those sound waves further with your jaw, tongue, and lips, send that sound on its way through the air till it reaches the eardrum of the receiver, which vibrates in a manner that tickles the cochlear cilia in their inner ear, which sends a patterned electrical impulse into their brain, which proceeds to decode that impulse into the same pattern of electrical impulses that constitute the same idea that you had in your brain.

Table 1.3: Examples of Communication Channels

| Verbal | Written | Visual |

|---|---|---|

| In-person speech | Drawings, paintings | |

| Phone conversation | Text, instant message | Photos, graphic designs |

| Voice-over-internet protocol (VoIP) | Report, article, essay | Body language (e.g., eye contact, hand gestures) |

| Radio | Letter | Graphs |

| Podcast | Memo | Font types |

| Voicemail message | Blog | Semaphore |

| Intercom | Tweet | Architecture |

To ensure that the message was appropriately decoded and understood, the receiver then encodes and sends an intentional or unintentional feedback message that the first sender receives and decodes; when the first sender understands that the receiver understood the first message, then the goal of the communication process has been achieved. If you stated, for instance, “I’m hungry,” and the receiver of that message responded by saying, “Me too. Let’s get a taco,” you can be sure that they understood your intended meaning without them stating that they understood. From there, the message and feedback can continue to cycle around in a back-and-forth conversation that exchanges new ideas and offers opportunities for the receiver of those messages to ask for clarification if understanding isn’t achieved as intended.

However, the receiver’s intentional or unintentional feedback message does not need to be in the same channel as the sender’s. If the receiver of the above “I’m hungry” message nodded and held up a cookie for you to take instead of saying anything at all, it would be clear from their intentional nonverbal expressions and actions that they correctly decoded and understood your meaning: that you’re not only hungry but also that your hunger would be somewhat relieved by the cookie at hand. And if the receiver responded in no other way but with a rumble of their stomach, their unintentional feedback also confirmed their understanding of the message.

As you can see, this whole process is easier done than said because you encode incredible masses of data to transmit to others all day long in multiple channels, often at once, and are likewise bombarded with a constant multi-channel stream of information in each of your five senses that you decode without being even consciously aware of this complex process. You just do it. Even when you merely talk to someone in person, you’re communicating not just the words you’re voicing, but also through your tone of voice, volume, speed, facial expressions, eye contact, posture, hand movements, style of dress, etc. All such channels convey information besides the words themselves, which, if they were extracted into a transcript of words on a page or screen, communicate relatively little. In professional situations, especially in important ones such as job interviews or meetings with clients where your success depends entirely on how well you communicate across the verbal and all the nonverbal channels, it’s extremely important that you be in complete control of all of them and present yourself as a detail-oriented pro—one they can trust to get the job done perfectly for their money.

Key Takeaway

As a cyclical exchange of messages, the goal of communication is to ensure that you’ve moved an idea in your head into someone else’s head so that they understand your idea as you understood it.

Exercises

- Without looking at the communication process model above, illustrate your own theory of how communication works and label the diagram’s parts. Compare it to the model above and discuss the advantages and disadvantages of each.

- Table 1 above compiles only a partial list of verbal, written, and visual channels. Extend that list as far as you can push it.