Introduction

Learning to do accents as an actor, or to teach accents as a coach or trainer, requires many skills that you must integrate in order to become successful at it, and to be able to learn new accents in a short period of time. Having a strong knowledge of all the sounds of the world’s languages is an important starting place, and in recent years, many are embracing the challenge[1]. Tackling the entire inventory of vowels, consonants, clicks, implosives, ejectives, and other tools of the International Phonetic Alphabet allows us to not only identify and describe the all sounds available to us, but also to perform them. But knowing how to pronounce an obscure vowel or diphthong isn’t of much use if you’re not sure where to put that sound, and when to use it—which words can you use a sound in? As accent actors or coaches, we frequently encounter situations where a vowel that works for one word is inappropriate for another, seemingly similar word, and we may be at a loss to figure out why. This book is focused on giving you the knowledge and understanding to successfully identify why vowel sounds change in accents, and how to explore these changes with confidence and skill.

What are “Lexical Sets”?

Created by John Wells in 1982 as part of his 3-book series Accents of English, Lexical Sets are a way of grouping all the words that share the same phoneme, “the smallest unit which can make a difference in meaning”[2]. Wells chose 27 Lexical Set Keywords to represent all of these vowel groups of English. For example, the keyword kit denotes all words that share the same vowel sound in their stressed syllable, regardless of spelling, so that bit, myth, guilt, and women are all part of the kit lexical set. Though the kit words all sound like each other within an accent, your kit and my kit might sound completely different from one another if your accent and my accent are not the same. Each set can be pronounced in many different ways in the broad range of accents of English. The vowels of these pronunciations can be called phones, though in this book I tend to just call them, well, vowels. But they can’t be just any vowel—though each lexical set may have many, quite different realizations in accents from around the world, they tend to sit in certain parts of the vowel space. Accent learners and teachers can explore the feel of a lexical set’s possibilities by trying on different phones that they might encounter over the course of their careers. Like trying on a corset or high heels for the first time, these new-to-you realizations of a lexical set may feel uncomfortable or wobbly at first, but exposure helps to familiarize your ear and your vocal tract to the possibilities inherent in the great varieties of English. Part of this OER’s role is to be the costume shop manager, who helps you try on a tail coat, a suit of armour, leather chaps, or a gold lamé vest.

Wells typeset the Lexical Set Keywords in small caps, and I’ve continued that tradition. In some cases, the typography available to some authors or publishers just doesn’t allow for small caps, so it’s quite common to see the keywords set in CAPITALS, as you might do if you used lexical sets in an email. (In this book, because of restrictions on how chapter titles can be formatted, I’ve had to format the keywords in capitals instead of small caps.)

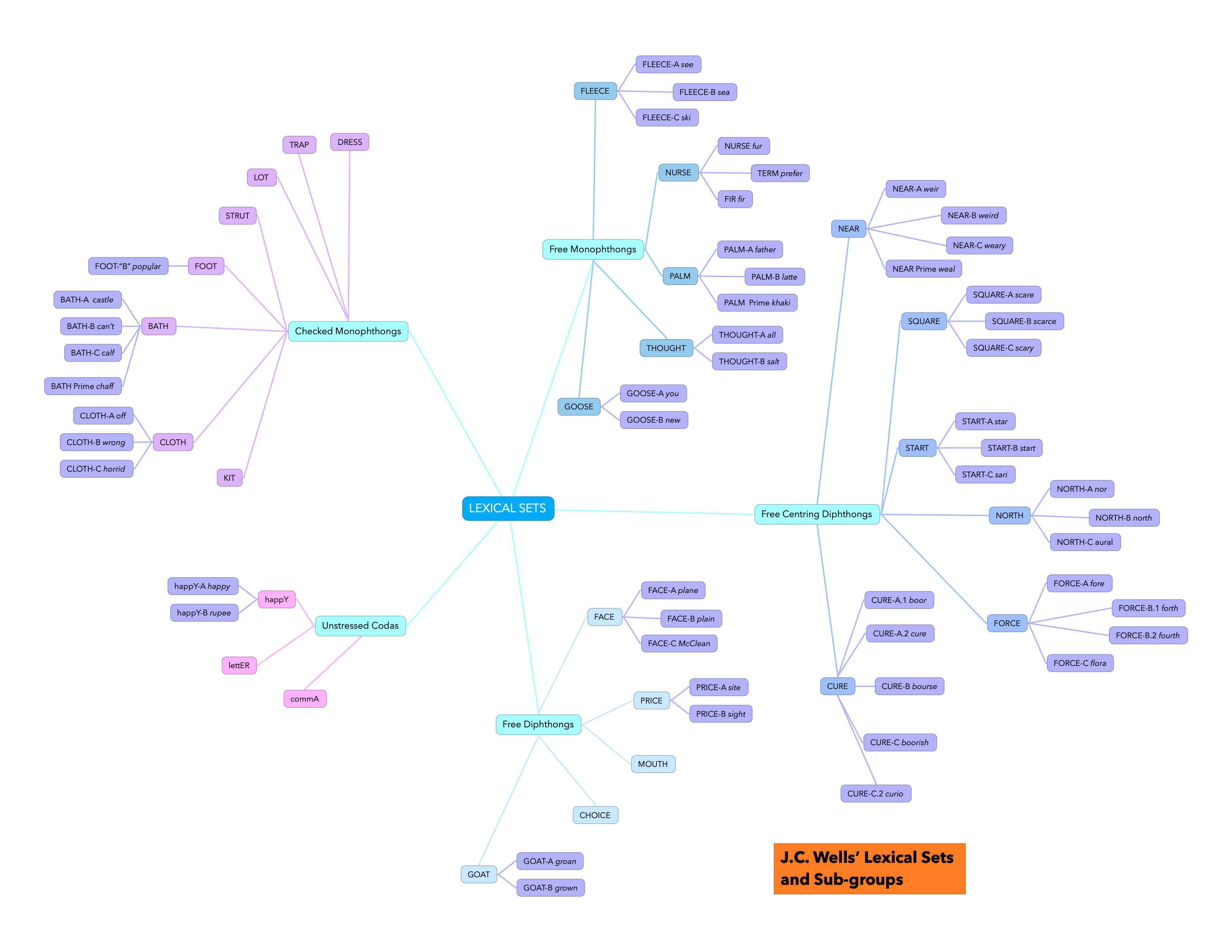

Wells framed his Lexical Sets using two “standard” reference accents of the time, Received Pronunciation (RP) from the south of Britain, and General American (GenAm) from the United States. While these reference accents continue to evolve, the sets remain the same, though the accents may use the sets differently than they did before, and the quality of each of the phones may slowly drift over time. No single accent has all the Lexical Sets. Each accent has some sets merged with others; many sets have sets divided into Subsets. These Wells labelled with Ⓐ, Ⓑ, Ⓒ and sometimes a subset labelled prime, a subgroup that frequently has variable, or inconsistent pronunciations. With all these sets and subsets, there are a total of 57 word groups that you might be expected to identify, based solely on Wells’ initial work. That’s a lot!

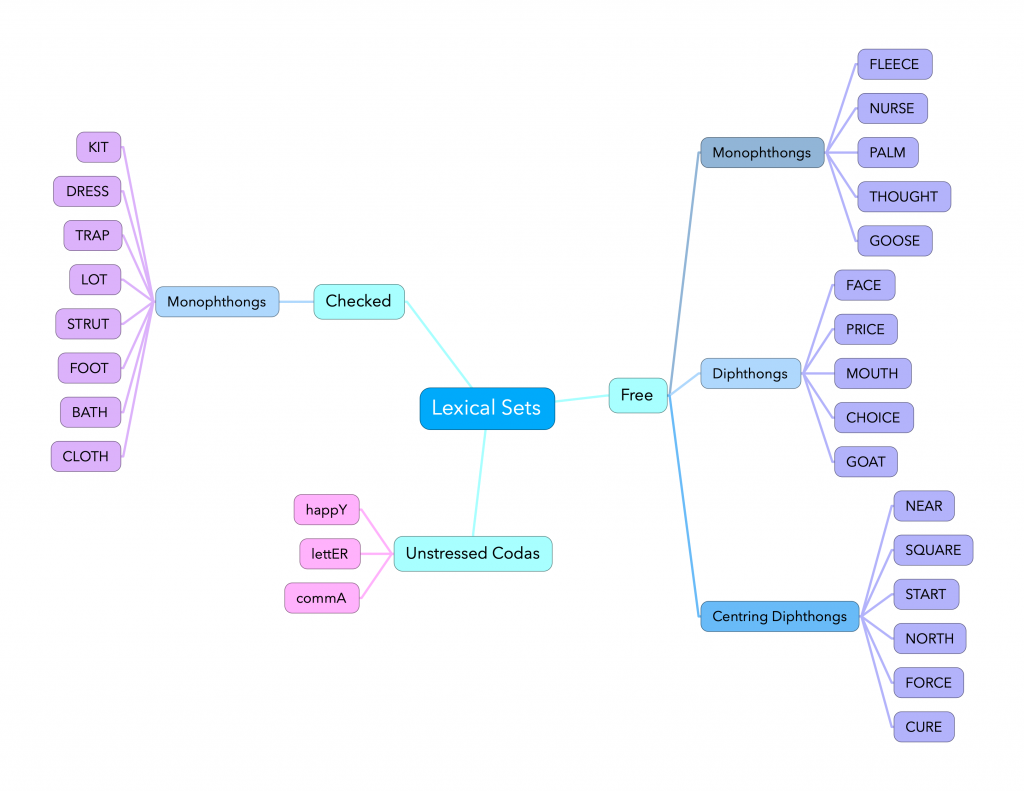

In organizing the sets for his book, Wells grouped the lexical sets by vowel categories which I find quite helpful, as each group behaves similarly. The groups are as follows:

- Checked vowels, such as kit or foot, which are ones that must only occur in a closed syllable, that has a consonant after the vowel.

- Free vowels, such as goose, face or force, which can be in an open or closed syllable, so they can have a consonant after them or they can be at the end of a word or syllable with nothing after them. Free vowels can be monophthongs, steady-state vowels that are in a roughly fixed position in the mouth, or diphthongs, which are gliding vowels that move from one vowel quality to another.

- Weak vowels, such as happy or letter, which are ones that are unstressable, usually described at the end of a word, in “Unstressed Codas.”

For the purpose of this book, I have chosen to subdivide the Free vowels into groupings that I’ve found helpful:

- Monophthongs, such as in fleece,

- Diphthongs, such as in choice, and

- Centring Diphthongs, such as in near, which offglide towards the centre of the mouth, where we find schwa (rhotic or non-rhotic).

The groupings perhaps betray a bias I have towards accents like my own, which is rhotic. It’s a bias because the sets within each of these categories may, at times, be pronounced in ways that are antithetical to the category I’ve placed them in. For example, the goose set, which I’ve categorized as being in the “monophthong” group, can be said with a rising diphthong, [ə̯u]; the set face, which is in the “diphthong” group, is pronounced as a monophthong, [e], in many accents; and the set start, which I’ve called a “centring diphthong,” is frequently a monophthong in non-rhotic accents, [ɑ], and, some might argue, can even be one in some heavily rhotic accents [ɑ˞].

In some ways, Lexical Sets were a reaction to the practice of representing both phonemes and phones using symbols from the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA). Some people term these uses as a “broad” transcription for a phonemic representation, and a “narrow” transcription for a phonetic one. Typically, a phonemic/broad transcription is written between slashes, /laɪk ðɪs/ while a phonetic/narrow transcription is written between square brackets [ləɪ̯k ðɪ̈s]. A phonetic transcription will allow for much more phonetic detail, often shown through the use of suprasegmental diacritics, which attempt to signal specific, though often very subtle, differences in the way a phone is articulated, in order to capture a more accurate picture of a particular pronunciation associated with a variety, accent, or idiolect. While you may encounter phonemic transcriptions of pronunciations that you find in dictionaries and in Wikipedia entries, and these are definitely very helpful, it is easier to use lexical set words when describing an accent. Rather than saying /e/ → [ɛ̞], as was the fashion when I was training to be an actor and coach, today we simple say that “dress is [ɛ̞].” This allows us to not have to agree on what symbol stands for the “idea” of the phoneme, and you can approach the new-to-you sound of dress from wherever it lies in your personal idiolect.

When an accent coach, phonologist or dialectologist researches a variant of English that has not been studied (much) before, they may discover that they need to represent new subsets of the Lexical Sets. Sometimes Wells doesn’t provide subsets for these varieties, or one may find that the labels of Ⓐ, Ⓑ, Ⓒ and prime which he used are somehow insufficient, or just not evocative enough for the task at hand, and so they may create Alternative Lexical Set Keywords in order to more easily identify these subsets. For example, in Scotland the nurse Lexical Set is subdivided essentially along the lines of how the words are spelled, with either an <i>, <e> or <u> and so linguists have dubbed these subsets fir, term, and fur. Though there is no standard way to represent Alternative Lexical Set Keywords, in this text I’ll identify them with italic small caps. So now we have far more than the original 27 sets!

Why Don’t I See Lexical Sets Everywhere?

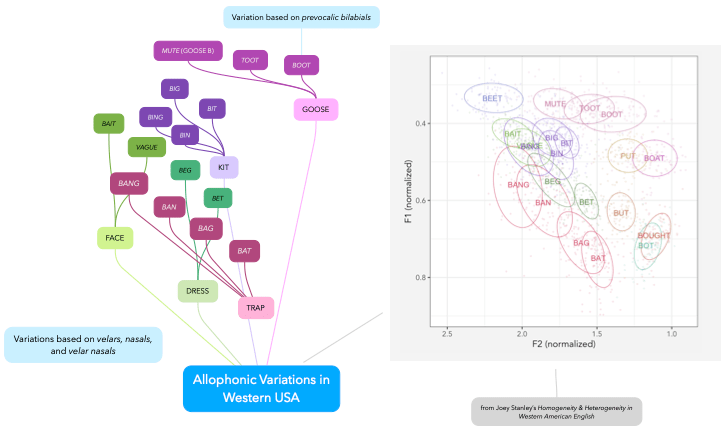

Over time, lexical sets have become much more prevalent—Wikipedia even uses them for the phonology of most accents of English it describes, and that’s because the scholars it references in developing their entries use Wells’ sets. However, some linguists still prefer to use minimal pairs to distinguish the vowels of English. The most common “setting” of this kind is <b_t> such as bit, bet, bat, bot, but, book*, beat, Bert, baht, bought, boot, bait, bite, bout, Boyd*, boat, beer, bear*, bar*, bore*, boor*. As you can see from the asterisks, there are many instances where there isn’t a <b_t> word for the Lexical Set. There simply is no single setting that capture all the vowel qualities of all the accents of English (or even just a single accent.) So linguists who choose to use minimal pairs must resort to other pairs in order to show the complete picture, the full nature of how the lexical set group behaves, and all its quirks.

Vowels have a tendency to behave differently in different environments. Because speech flows from one segment to the next, as our articulators shift rapidly from one place in the mouth to another, there are some effects that happen. We may anticipate a sound that follows, by shaping part of the vocal tract a little in advance of it, or we may preserve an aspect of an articulation after the fact. As a result, many linguists will look at minimal pairs within a lexical set through settings like <bɪ_> such as bit, bing, bin, big in order to compare how different consonants affect the vowel.

What’s the problem with Learning Lexical Sets?

Unfortunately, there is just so much to know, so many lexical sets to remember. An aspiring accent actor or coach will likely want to know all the sets, all the subsets, and have a sense of which sets might overlap. But you may quickly find that it really is an information overload: how much is enough? Maybe you don’t have to memorize everything, but a strong familiarity can be very, very valuable in trying to figure out why a speaker speaks in the way that they do.

On top of all that there is to learn, your personal accent or idiolect may cause some cognitive dissonance, and make certain sets less accessible, especially sets that are merged for you. For example, lot/cloth differentiation for folks who have them merged in their idiolect is a definite challenge, and requires specific study. Sometimes, a lexical set requires some Subset specificity which can be either allophonic or historical. Allophones are variations on a phoneme that occur in a specific setting. There are some particularly challenging environments that come up frequently, e.g. before /l/ or /r/, or before a voiceless consonant, and so you begin to learn over time when there might be variants that are worth noting. The “historic” variations are often due to the fact that a lexical set may have undergone a merger in the past that the average speaker is oblivious to, apart from differences in spelling. For example, the fleece lexical set in its current state is a merger of words like see, spelled with <e> or <ee>, that used to be pronounced with /e/ (similar to how face is pronounced today in many accents), and words like sea, spelled with <ea>, that were pronounced with /ɛ/ (similar to today’s dress). Some accents preserve the dress-like pronunciation, so knowing about this potential historic allophone can be very helpful. Both types of variation create a kind of subset of the lexical set, so having practice word lists and sentences with these separated out in this manner can be very helpful when learning or teaching a new accent that features them. If you aspire to have a strong grasp on these kinds of variants, developing a deeper understanding of how lexical sets relate through careful study of the Phonological History of English from the Great Vowel Shift [3] onward would be time well-spent.

While some sets and subsets can be differentiated by spelling, which you will want to learn, others require complex phonological rules (and brute force memorization) to differentiate. For example bath, with its relationship with trap and palm, or cloth and its relationship with lot and palm, have so many exceptions to which words are in one set and not in another, that considerable study and experience with these sets is required to feel confident in their use.

In some accents the keywords that Wells chose for the Lexical set names may actually be part of a different set, or allophonically different in an accent/idiolect. For example, in many parts of North America, the word palm is pronounced with an /ɫ/ after the vowel, and it tends to affect the quality of the vowel that precedes it, so that for many speakers, the keyword palm is an allophone, and it no longer sounds like the majority of other members of the set, that lack pre-lateral setting (before a dark /l/). It may be useful to practice an “accented” version of lexical set keywords as a way of getting away from any assumption that there is a “correct” way of pronouncing them. Whether your idiolect features velarized (dark) /ɫ/ in palm or not, why not use a different accent when saying it, with a little nod and a wink to acknowledge that it can be said in any way.

Another problem you might face when learning the lexical sets is a frustration around a lack of a full set of Alternate Lexical Set names for subsets (like the thoroughly forgettable fleece Ⓐ, Ⓑ, Ⓒ), and allophonic sets. If only there were more alternates, like the ones we find for the allophonic variant for goat+/ɫ/, goal, or price before a voiced consonant, pride! At this time, this book doesn’t attempt to create new Alternate Set names, though maybe in the future it could.

As post-vocalic /-l/ and /-r/ are so frequently problematic, I’ve chosen to comment on how they might affect articulation for each lexical set in the word lists. The rich and complicated variety of subsets before /r/ can be especially complicated. Not only are the so-called Centring Diphthongs challenging, but also many checked vowels before /r/ provide another hurdle for you to get over: trap + /r/, kit +/r/, etc.

For rhotic speakers it may be slightly more challenging to address than for non-rhotic ones, though I feel that having speakers from either side of the rhotic-divide explore what life is like on the other side of the border is an extremely valuable challenge. Hopefully learners will appreciate the opportunity to explore more deeply.

What about Consonants?

Wells’ version of the lexical sets was focused only on vowels. However, that hasn’t stopped other writers/researchers from creating them for consonants. For example, Raymond Hickey in creating his work on Irish English coined a series of lexical set keywords for the consonants he felt were needed to describe it accurately. At this time, I don’t believe that there is a dominant model for the use of lexical sets for consonants. Perhaps a future edition will include a focus on consonants as well.

Raymond Hickey’s Consonantal lexical sets needed for Irish English[4]

| Dental stops/fricatives | Alveolar stops |

| think /t̪ (θ)/ | two /t-/ water /-t-/ get /-t/ |

| L-sounds | R-sounds |

| rail /-l/ | run /r-/ |

| look /l-/ | sore /-r/ |

| Velar stops | Velar nasal |

| gap /ɡ̤-/ | talking /-ŋ/ |

| cap /k-/ | |

| Alveolar and Alveolo-palatal sibilants | |

| shoes /ʃ/, /z/ | |

| Labio-velar glide, voiced and voiceless | |

| wet /w-/ | which /hw-/ |

Other Challenges and Oddities

When Wells created the lexical sets, they were devised for stressed syllables. However, all the vowels of English can also appear in unstressed syllables. So, how should vowels in unstressed syllables be handled? I debated with only providing examples in stressed syllables, but in the end decided that it would be more helpful to provide examples in the word lists of unstressed syllables as well.

In writing this text, I have chosen to use phonetic transcription for much of what I am describing, wanting to capture as much detail as possible. However, I will use phonemic transcription occasionally, and when I do so, I’ve opted to avoid the length marks associated with the traditional, Daniel Jones-esque, phonemic representation. For those unfamiliar with this style of transcription, Free vowels are described as “long” and have the diacritic mark beside them, such as [iː, ɜː, ɑː, ɔː, uː]. In this style of phonemic transcription, these diacritics are added regardless of the length of the actual pronunciation, so the vowel in beat /biːt/, which has a much shorter vowel, is transcribed exactly the same as bee /biː/, whose vowel is much longer. Back in the day, when typography was done with little pieces of lead type at the printers, phoneticians tried to simplify things by using /i/ for kit and /iː/ for fleece. That’s no longer part of the tradition, so I’ve gone one step further and abandoned the length marks everywhere. Call me a rebel.

In exploring the Mergers and Splits of each lexical set, I try to offer the more commonly used terminology when it’s available, where the merger or split is described by a minimal pair rather than by the lexical set names. For example, many folks will have heard of the pin/pen merger of the US South; that’s much easier to say than kit/dress before nasals! Frankly something like the Mary, marry, merry merger/contrast is much more memorable. On the other hand some mergers, like square -near, are just as well served by the lexical set keywords as they are by something like bear=bare/beer. Note that, in this text, the word/keyword that goes first in a merger is the target that the second word has been drawn into. So in this last example, beer sounds like bear=bare, not the other way around.

How Can I Learn the Lexical Sets?

The first thing to do is to get your head around the 27 major lexical set keywords: learn their “names.” You can do that by brute force, but I would recommend having more fun with it than that. For example, you can learn it as a song, use emoji to learn them, or draw pictures of them as you say them.

SONG

I have created a song, to the tune of Frère Jacques, that you can try out here.

VIDEO

I’ve also created a video, which you can watch here.

FLASH CARDS

I feel that one of the best methods is the spaced repetition method with Flash Cards, real or virtual. I’ve created a series of flashcards that use words and images for you to practice.

WORD SEARCH

Here’s a word search, to help you practice remembering the names of the lexical sets.

DRAG THE WORD

- Thanks in no small part to the influence of Knight Thompson Speechwork, which has championed this approach so successfully. See ktspeechwork.org⧉ for more information. ↵

- Trask, R. L. (Robert Lawrence). A Dictionary of Phonetics and Phonology [electronic Resource], p. 264. Routledge, 1996. ↵

- The Great Vowel Shift (1400–1700) changed the pronunciation of the English language through a series of shifts primarily to the long vowels, and to some consonants, which became silent. ↵

- https://www.uni-due.de/IERC/IERC_Phonology.htm ↵

In a given language variety, the smallest unit which can make a difference in meaning, which contrasts with other phonemes. To some degree, it is a concept, an idea in the mind that is in someway related to the phonetic reality of what a speaker says (a "phone".)

A single phonetic segment, as actually realized through speech. It is the sound output of the mental concept of the "phoneme".