2 The syllabus

In this chapter, we describe ways that the syllabus can be made more approachable and be used to communicate the inclusive nature of your course. First impressions count, and the syllabus serves this purpose. Since the syllabus is the students’ first contact with your course, this is an opportunity to communicate your intentions and create the environment you want for the course. While there are required elements, there is lots of room for your own voice and approach. “Accessible Syllabus” provides excellent recommendations for making the syllabus more readable, accessible, and additional tips on how to set and sustain an inclusive tone.

Sections in this chapter:

- Core principles

- Elements the syllabus has to include

- Developing a tone of welcoming and inclusion

- Decisions about course resources

- Communication

- Learning outcomes

- Grading policies

- People things happen to people

Starting principles

The course’s syllabus needs to convey information to students that will be fundamental to their success. The information a syllabus contains needs to be easy to find and easy to understand. These characteristics are also part of engaging in inclusive teaching. Yet, reading the syllabus is likely to be the first interaction a student has with a course. Sure, the syllabus can take a “just the facts” tone with students, but this misses an opportunity to welcome students actively to a new learning experience.

As you launch into teaching, it’s a good time to examine your own assumptions, however many times you may have done so before. Are all the students equally ready to take on this new challenge, whether academically or in terms of their past experiences? Remember that the ongoing pandemic has created, for many, a sense of isolation that is distinct from what most present-day instructors have experienced in their own academic or personal backgrounds. For others, pandemic-related isolation might well be a relatively minor issue, given that many people have experienced grave personal challenges and losses that might make starting something new more difficult.

Students will need to demonstrate their capacity to learn the material courses convey, so setting an inclusive and welcoming tone at the outset of a course does not dilute the rigour of the course’s content. The objective of evaluating students’ learning in a course is to encourage them to learn course content well and to be able to apply it to solving problems. Another objective is likely to help students build foundations for more advanced learning and perhaps to impart professional skills as well. Conversely, the course should not apply a filter to students at the outset, tacitly encouraging students who fit the unconscious starting assumptions of the instructor, and discouraging others.

The syllabus is a place where you can embrace the diversity of all students, while still being clear about your expectations and pathways to success in the course.

Remember to share the document with students in an accessible format and share it in a small file size (e.g., as a PDF set up for electronic distribution and accessibility).

Elements the syllabus has to include

There are some items that a syllabus has to include. For uOttawa, the list is below and is provided in the Academic Regulations:

- the course description approved by Senate;

- learning outcomes,

- teaching methods;

- assessment methods and weighting of grades;

- a list of required and recommended readings;

- a calendar of activities and evaluations;

- course attendance requirements;

- the professor’s contact information and office hours;

- a reference to the regulation on plagiarism and academic fraud;

- a statement that assessments can be written in French or English.

Starting to seem long? A little dry? Students will likely not take in the entire syllabus in a single sitting and that’s okay. The syllabus is their road map and reference document for important information in the course, which they can consult as needed. You may want to highlight various aspects of the syllabus at various times in your course, such as expectations about academic integrity leading up to major assessments and student resources throughout the course.

Rather than only stating regulations at students (the “just the facts” approach), which can come across as patronizing and impersonal, consider explaining why you value critical teaching practices. Academic integrity matters enormously as a matter of equity, for example, not simply because universities have rules about it. Cheating creates academic outcomes that do not reflect the effort that students put into their learning, subverting learning objectives and potentially contributing to perverse outcomes when scholarships are awarded. Maintaining standards around academic integrity is in the interests of students, in other words. There are learning opportunities for students, even at such moments, that might lead to better understanding of the challenges that professors must also meet. A little mutual understanding is always a good thing, and illustrating that you care about why rules matter, not just that there are rules, can help students see past the imposition of conditions on their conduct to a deeper perspective.

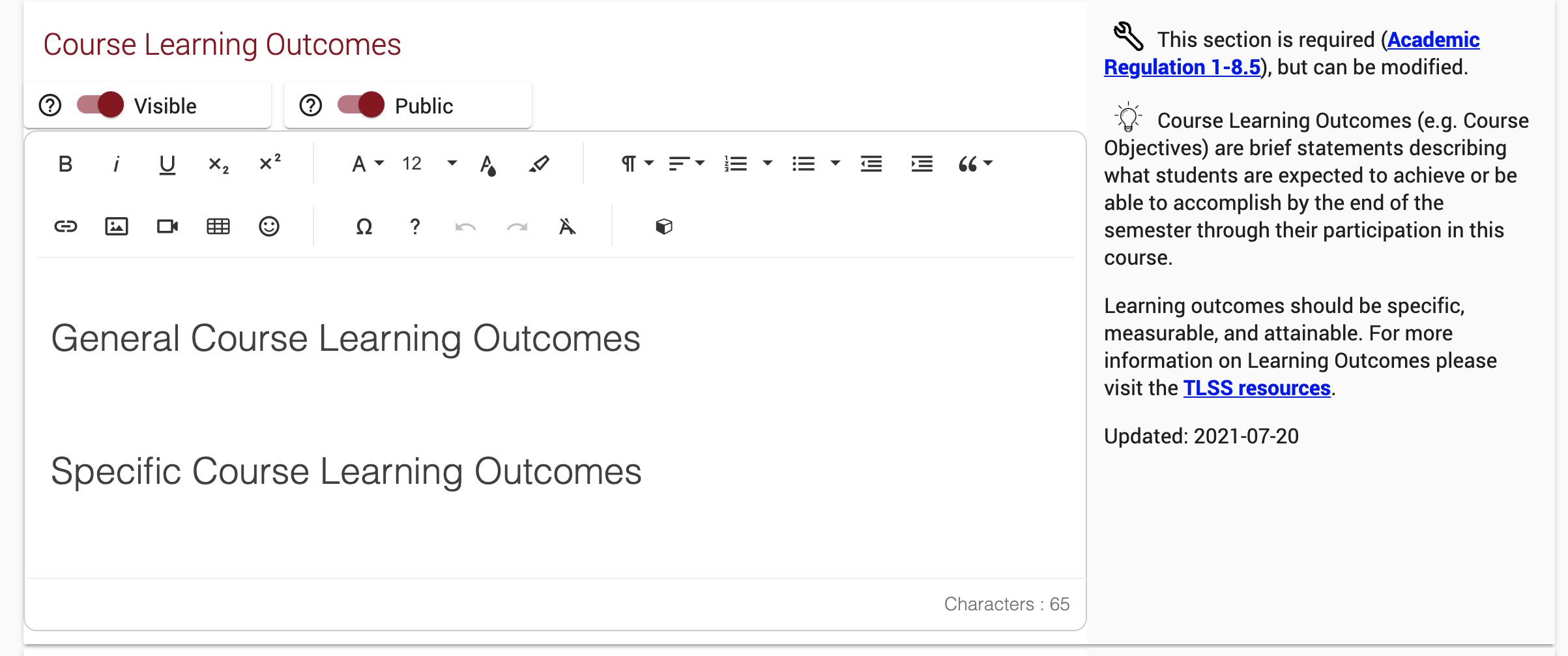

Many institutions provide a template that can be used to make the job easier. uOttawa currently uses Simple Syllabus, a cloud-based syllabus template that is accompanied by university regulations and recommendations for creating the syllabus. Systems like this are great for ensuring your syllabus includes everything your university requires. The key thing is to ensure the content is there, not that you follow a pre-defined format. For most of the required elements, you can choose the tone and wording. More on that in the next section.

Developing a tone of welcome and inclusion

As the first document the students read in the course, the syllabus is a great place to welcome students and prepare the environment you want for the course. For example, you can introduce yourself and teaching assistants, including pronouns (bear in mind that sharing pronouns is optional).

First impressions are made quickly. Set the tone when you start.

You can also include a statement about diversity and inclusion, which provides a chance to welcome all students to the course and to demonstrate that you care about doing so. However this is done, it is far better to include such a statement (even if you feel it is imperfect) than to avoid the matter entirely. You could also include a specific statement that you will work with students to implement approved accommodations (e.g., academic, religious, illness) or other flexibility that you include (e.g., sliding scale on a grading scheme).

Statements regarding diversity are likely to convey sincerity more effectively if they are personal to the instructor. It is easy to quote regulations or standard policy comments at these junctures, but that approach can be mistaken as performative, and the appearance of insincerity is antithetical to the aim of welcoming students of all backgrounds.

- uOttawa’s Indigenous affirmation

- native-land.ca: an interactive map of Indigenous territories around the world

- Canadian Association of University Teachers’ Guide to Acknowledging First Peoples and Traditional Territory

- Territorial acknowledgements: Going beyond the script

Course content sometimes takes a “colonial” tone, overwriting or ignoring Indigenous peoples’ experiences, knowledge, and precedence in history. Decolonizing curricula effectively requires thoughtful consideration of bias and conveying these views to students is worthwhile, even if completely eliminating such biases is a longer process. For example, one of the authors teaches ecology, and part of the history of this field, in a western scientific sense, is the pioneering work of 19th century naturalists, such as Darwin. Describing his work as stemming from “voyages of discovery” is accurate, on one hand, in that Darwin made observations leading to unique and new hypotheses about the evolution of life on Earth. On the other hand, most of the places he and other naturalists went had been occupied and shaped by human cultures for thousands of years or longer. The peoples in such areas, like the Amazon, had and have profound knowledge of their environments and the organisms that share them, and most of this wisdom was unacknowledged in the development of western science. The beginning of knowledge about how the world works is often treated as when western science first turned its sights on a particular topic. This view can be too narrow, in many contexts.

Yet, decolonizing a curriculum can be a long term challenge and consulting with Indigenous scholars and colleagues can help accelerate such an effort, and with reconciliation.

The UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples notes (Article 15:1) notes that: “Indigenous peoples have the right to the dignity and diversity of their cultures, traditions, histories and aspirations which shall be appropriately reflected in education and public information.” Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission identified a series of key principles and concluded with a series recommendations that are relevant to remodelling education to be more respectful of Indigenous cultures. Among these is the recognition that, “Reconciliation requires constructive action on addressing the ongoing legacies of colonialism that have had destructive impacts on Indigenous peoples’ education, cultures and languages, health, child welfare, the administration of justice, and economic opportunities and prosperity.” Surely, overwriting or failing to acknowledge Indigenous cultures is not in keeping with such aims.

Finally, we note that acknowledging the value of Indigenous inclusion explicitly sets a valuable and positive example for students, whether there are Indigenous persons in a particular course or not.

A note on gender declarations

Some people identify their gender (e.g., she/her, they/them) when they introduce themselves, in their signature, etc., including professors in their syllabi. A core reason for stating pronouns is to communicate that everyone is welcome in the course, including people of all genders. Declaring gender is completely optional; you, the teaching assistants, or students may not wish to do so. While there are good reasons for some to declare their gender, there is an endless array of reasons why people may not want to do so (imagine someone transitioning, for example). Such a declaration should remain a personal choice. Nevertheless, there is an important distinction between welcoming and embracing gender diversity (do this), versus forcing a choice upon others to declare their gender publicly (don’t do this).

In a related vein, there are a number of resources to learn more about sexual identity; UBC has created an infographic that can serve as a starting point.

Decisions about course resources

Textbooks and other course materials

As you make decisions about which textbook or other material to use in the course, choose accessible ones, respect copyright, and consider selection criteria that include EDI concepts: what experts (e.g., scientists) are represented, how are discoveries described, what kind of language does the resource use? For example, Diversity Chemistry is a site that can help find diverse examples of chemists who work in a variety of fields.

If you have any questions, the Library’s experts are available to support you—be sure to give them enough time to answer your questions or for additional support. For example, if you need to scan materials, the library’s Course Reserve Service (using Ares at uOttawa) can scan these for you, in an accessible version. If you’re showing films or videos, the library can support you in adding captions (and meet AODA requirements); they do need sufficient advance notice (e.g., 1 – 6 weeks).

Open Education Resources (OERs)

Consider using Open Education Resources (OERs) in your course. OER are “learning and teaching materials that are freely and openly available”. They range from textbooks to entire courses and everything in between, including videos, podcasts, tests and exercises, websites, software, simulations, case studies, presentations slides, and more. The key is that they can be widely distributed and adapted because they are at no cost to the user and are not subject to the usual copyright restrictions. This openness is most often indicated by a Creative Commons licence.” –uOttawa Library

Benefits of OERs

Based on uOttawa’s description, here are some key benefits of OERs:

- OER are affordable for students, making education more accessible.

- OER allow you to customize and adapt to the course context, providing a richer teaching and learning opportunity.

- Students can benefit from multiple learning styles because OER can incorporate various content formats (text, audio, video or multimedia) and interactive elements.

- Remote and continued access since most OER are digital, do not require an access code and do not expire.

- Contribute to students’ success and completion by easing their financial burden without having a negative impact on their learning (e.g., Bol et al., 2021)

Finding OERs for your discipline

You can find OERs through your library (e.g., uOttawa Library, by discipline) and other sources such as eCampusOntario and BCcampus.

Communication

Students can be intimidated by the idea of speaking with a professor—with you. 🙂 Introducing yourself is one of the ways you can become a little more approachable. Encourage students to connect with you and other members of your instructional team.

Some professors find that their office hours are not well-attended. There can be a few reasons for that, such as mis-matched schedule, difficulties finding or accessing the prof’s office, students not knowing what office hours are for, or students being intimidated by approaching the professor. Professors have taken a number of approaches to encourage students to make contact, described in the Chapter on course content and classes.

Learning outcomes

While this eBook talks primarily of changes the educator can make to create more inclusive course environments, we can also have expectations of the students’ knowledge, skills, and values with respect to equity, diversity, and inclusion as they complete a course or program. Much like other professional skills that students are expected to develop (e.g., teamwork, communication), what are your expectations for students’ learning in your course or program with respect to EDI?

Some examples could include the following, which are based on uOttawa’s chemistry graduate program-level learning outcomes and other sources:

- Demonstrate and promote academic and professional integrity, including:

- EDI-related knowledge, skills, and values and strategies to improve EDI (equity, diversity, and inclusion)

- Ethics in conducting experiments/studies and analyzing findings

- Identifying potential conflicts of interest.

You may decide to ask students to self-assess these skills and later develop formal assessments (formative or summative).

Grading policies

Share your policies and procedures for for missed assessments, considering the language you want to use (e.g., Accessible Syllabus) and your institution’s existing policies (e.g., uOttawa’s academic regulations).

People things happen to people

All sorts of issues can arise for students (or ourselves!) during a semester, such as a sick family member, caring for siblings, technical issues, etc. You can consider other ways to incorporate flexibility in the course without adding to your own workload, such as allowing students to drop the lowest quiz/assignment mark or allowing multiple formats for an assignment submission.

Including other sections can also help students learn policies, regulations, and resources of the institution, including academic integrity policies, mental health, bilingualism (e.g., being allowed to write assessments in French or English), and Academic supports.

In summary, the syllabus is an opportunity for inclusion, to engage with students and set a welcoming tone for the course!

OER are "learning and teaching materials that are freely and openly available. They range from textbooks to entire courses and everything in between, including videos, podcasts, tests and exercises, websites, software, simulations, case studies, presentations slides, and more. The key is that they can be widely distributed and adapted because they are at no cost to the user and are not subject to the usual copyright restrictions. This openness is most often indicated by a Creative Commons licence." –uOttawa Library

The premise of inclusion should be thoroughly uncontroversial. The job of professors, instructors, and educators of all kinds is to offer each student in their classes the same opportunities to learn and expand their horizons. It is part of the basic definition of what it means to do this job. That educators - particularly those who are interested in reading a book of this kind - want all their students to succeed is axiomatic.

Conversely, the challenges of learning can differ enormously among individuals, and many of those challenges align with their identities, cultural backgrounds, privileges, and capacities. None of these characteristics predicts talent for any discipline. Yet, student success nevertheless correlates with individual characteristics. While the idea of inclusion - what we refer to as "inclusion by default" - is uncontroversial, achieving an inclusive learning environment can be challenging, potentially leading to systemic exclusion of students for reasons that are unrelated to ability, effort, or ambition. This is the antithesis of what educators aim to achieve.

The challenge is made greater because learning spaces are also inequitable by default. The educator has particular responsibilities and authority, and wielding that authority carefully and in the interests of all students is simply hard to do well all the time. After all, the responsibility for selecting a curriculum, designing course content, choosing example to make concepts more concrete and relatable, and evaluating students all rest largely or entirely with the educator.

Finally, educators are models of academic success. A professional educator is likely to have some combination of academic talent, good fortune, and privilege that meant they could pursue and succeed at academic work at its most advanced levels. After all, if university courses worked for the educator, why shouldn't similar courses work equally well for each subsequent student? There may be times this seems like it must be true. For example, hard work is critical to success, and becoming a professional educator certainly requires a lot of hard work. Maybe students should just put in the same effort, and might their success not then be limited only by their intrinsic talents? Even this simplistic view is a fallacy of privilege. Leaving aside such critical challenges as historic and present-day discrimination, many students cannot dedicate their time purely to learning because their economic circumstances require them to hold down part-time or full-time jobs to enable them to pay for their education or support family. A pathway that worked for an educator may be unavailable to her or his students.

The triple issues of learning and practicing teaching philosophies that are inclusive by default, managing the intrinsic inequity of nearly any conventional learning environment, and taking account of personal privilege in helping students learn are key motivations for preparing this book. To these, we add that many educators can also experience discrimination or be targeted by colleagues and even students because of their identity. Women professors, for example, are perceived as less capable than equally qualified male colleagues and this inequity translates to differences in how students evaluate professors.

In other words, this book is intended to

Another

One of the the challenges intrinsic to learning is that classrooms and teaching labs are Classrooms and teaching labs are inequitable by default, which is not something that educators recognize intuitively.

Terminology: using the federal framework for designated groups to make alignment with national policies easier to see.

What are the problems students experience in classes where inclusion is not built in convincingly? - physical disabilities for one, even just accessing a room, cultural reference points can be difficult when

perfection vs progress

OK to make mistakes - intention matters. Everyone stumbles or misspeaks sometimes. Avoiding the issue is not

-inclusion can be fun.

-inclusion by default rather than initiated on the basis of traditional thinking, then patching stuff on top of that. The difference this creates is important: performative vs substantive.

[paragraph about importance of inclusion and equitable access to education]

In what ways can inequities arise?

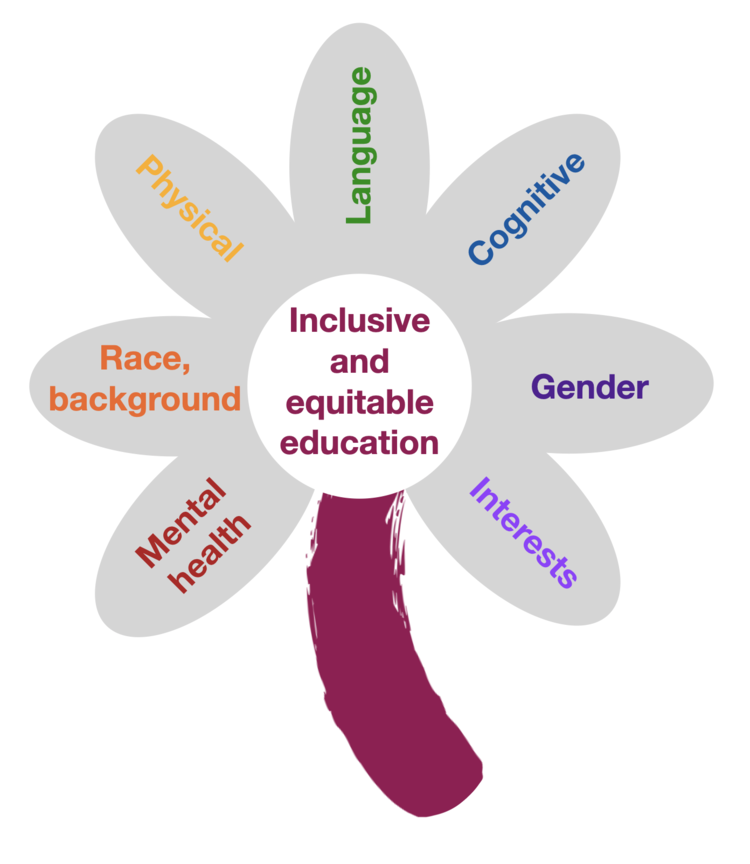

Inequities arise in many ways; some are predictable and visible, while others are not. Improving equity and diversity in education involves many components, including physical, cognitive, emotional, race, background, gender, language, interests, mental health, and wellness.

Our actions in our courses can directly impact students, their education, and their careers. The following examples come from current and recently-graduated students at Ottawa.

[add experiences and useful approaches/solutions]

As educators, what can we do?

We don't have to be experts in this area to make our courses more inclusive. In this resource, we suggest ways to start making our courses more inclusive, as well as further readings and resources. There is no single, correct approach, nor is there a need to do everything at once. Instead, we suggest trying a few things, connecting with and listening to students, then building on those first steps.

We can also work to identify our own privileges and biases. Project Implicit is one place that aims to identify implicit biases.

Are you designing a new course, teaching a course for the first time, or ready to take a step past this guide? Consider connecting with an educational expert at the Teaching and Learning Support Service and/or Library. They have expertise in designing for educational accessibility and inclusion, using frameworks such as Universal Design for Learning.