1 Introduction

Welcome!

We’re glad you’re here and are interested in how education could be made more inclusive. In this introduction, you’ll find some background information on issues surrounding inclusion in education, some groups and aspects to consider when thinking about course changes, and how reflecting on ourselves plays an important role.

The book is organized in the same way many of us prepare our courses, starting with the syllabus, intended learning outcomes and course structure, moving through to course content (e.g., classes, notes, activities), environment, assessments, and other aspects of instruction and design.

Nous avons aussi une version française. We also have a French version.

Introduction

A central role of professors, instructors, and educators of all kinds is to offer each student opportunities to learn and expand their horizons. It is part of the basic definition of what it means to do this job. That educators want all their students to succeed is axiomatic, particularly for those who are reading a book of this kind. We are not deliberately trying to exclude students or make learning harder for some than others.

Nevertheless, the challenges of learning can differ enormously among individuals, and many of those challenges align with their identities, cultural backgrounds, privileges, and capacities. None of these characteristics predicts talent in any discipline. Yet, student success nevertheless correlates with individual characteristics (Caballero et al. 2007, Wei et al. 2018). In other words, characteristics do not predict talent, but characteristics do relate to success. The inclusion gap is the space between talent and success, and it is created, in part, by obstacles to inclusion that we hope this resource might help reduce or eliminate.

While the idea of inclusion — what we refer to as “inclusion by default” — ought to be obvious, achieving an inclusive learning environment can be challenging. Failures to account for diversity in learning environments can lead to systemic exclusion of students for reasons that are unrelated to their ability, effort, or ambition. This outcome is the antithesis of what we aim to achieve as educators.

The challenge is made greater because learning spaces are inequitable, rather than inclusive, by default. As educators, we have particular responsibilities and authority, and wielding that authority carefully and in the interests of all students is simply hard to do well all the time. After all, the responsibility for selecting a curriculum, designing course content, choosing examples to make concepts more concrete and relatable, and evaluating student learning traditionally rest largely or entirely with us.

Finally, educators are models of academic success. That kind of success can pose a daunting problem for students. A professional educator is likely to have some combination of academic talent, good fortune, and privilege that meant they could pursue and excel at academic work at its most advanced levels. If university courses worked for the educator, why shouldn’t the same courses work equally well for each subsequent student? There may be times when this seems like it must be true. For example, hard work is critical to success, and becoming a professional educator certainly requires a lot of hard work. Maybe students should just put in that sort of intense effort, and then their success might be be limited only by their intrinsic talents? Even this simple view — commonly held — is a fallacy of privilege. Leaving aside such critical challenges as historic and present-day discrimination, many students cannot dedicate their time purely to learning because their economic circumstances require them to hold down part-time or full-time jobs to enable them to pay for their education or support family. A pathway that worked for us as educators may be unavailable to the students in our courses. The road we took to academic excellence may simply be inaccessible or impractical for many students.

The triple issues of practicing teaching philosophies that are inclusive by default, managing the intrinsic inequity of nearly any conventional learning environment, and taking account of personal privilege in helping students learn are key motivations for preparing this book. To these, we add that many educators can also experience discrimination or be targeted by colleagues (and even students) because of their identity. Women professors, for example, are often perceived as less capable than identically (or less) qualified men colleagues and this inequity translates to differences in how students evaluate professors (Langbein 1994, Mitchell and Martin 2018). Discrimination and bias should have no place in education (or anywhere else). Yet, educators can be subjected to the same, caustic forces as students.

All too often, we have seen advocates for inclusion offer unconstructive critiques or attacks on efforts to improve equity in academic environments. Obviously, intolerance in this context is intensely hypocritical and leads to exclusion and gatekeeping. As authors of this resource, we recognize that we carry our own biases, learned from lifetimes of living in society. Our shared aspiration to eliminate prejudice cannot heal the lived (and sometimes life-altering) experiences of our students and colleagues in being singled out, called out, or labelled because of their identities. A university course cannot wash away such things either. But it is imperative that university courses should never be places where such exclusion is perpetuated.

So, the fundamental goal of this book is to suggest ways to do better using a framework that aligns with fairly common approaches to conceiving, designing, and teaching a university-level course. Perfection, which is subjective in this context in any event, should not be the enemy of progress. In writing this book, we know that we have done so far from perfectly, but we nevertheless hope that our efforts can help make a difference. As educators, we are uniquely positioned to make a positive difference in students’ lives and careers. It’s worth it.

As educators, what can we do?

There is no single, correct approach, nor is there a need to do everything at once. We don’t have to be experts in this area to make our courses more inclusive. In this resource, we suggest simple ways to start making our courses more inclusive and further readings and resources. Instead, we suggest trying a few things, connecting with and listening to students, then building on those previous steps.

As a starting point, we can work to identify our own privileges and biases. Project Implicit is one place that aims to identify implicit biases; the Canada Research Chairs’ Unconscious Bias Training Module is another. Training for ourselves can also include mental health (e.g., More feet on the Ground) and sexual assault support (e.g., Training on sexual violence support).

Are you designing a new course, teaching a course for the first time or wanting to take steps past this guide? Consider connecting with an educational expert in your Teaching and Learning Centre (e.g., Teaching and Learning Support Service at uOttawa) and/or Library. They have expertise in designing for educational accessibility and inclusion, using frameworks such as Universal Design for Learning. The chapter on Designing a course from scratch has more information.

In what ways can inequities and barriers arise?

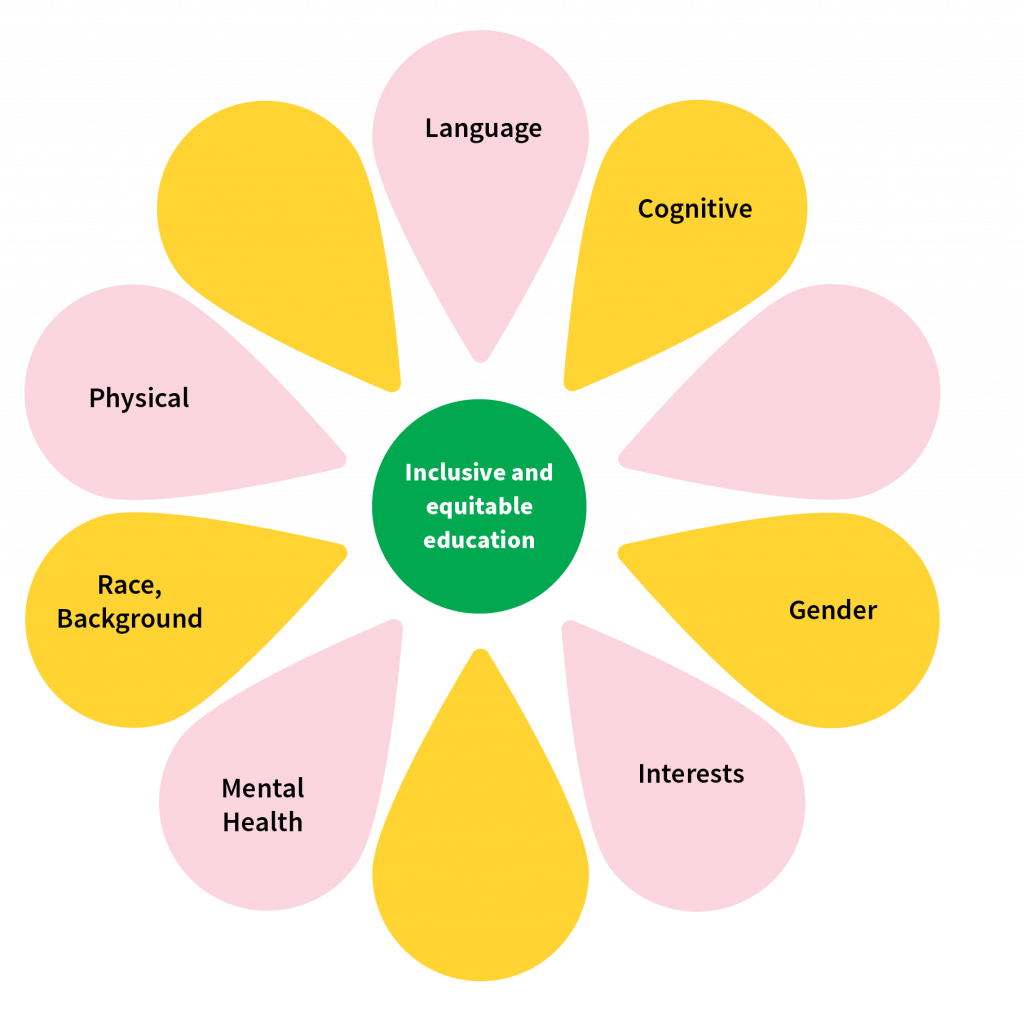

Inequities arise in many ways; some are predictable and visible, while others are not. Improving equity, diversity, and inclusion in education involves many components, including: physical (e.g., diversity, disabilities), cognitive (e.g., neurodivergence, attention deficit disorder), emotional, race, background, gender diversity, language, interests, mental health, wellness, and competing interests (e.g., family, school, athletics, job). We hope you find some useful suggestions in this guide to do just that.

Our actions in our courses can directly impact students, their education, and their careers.

A key idea behind making education more equitable is that learners may follow different paths as they progress toward the same learning outcome. A student with attention deficit disorder may need a quiet work environment to work through complex problems; a student with a back injury may need a standing desk. In each case, the learner has the opportunity to demonstrate that they can achieve the same learning outcome, simply using a different path. We dive into specific accommodations and general approaches to making an overall course more inclusive through the eBook.

Another key idea is making education more inclusive, which can involve simple statements of welcome and showing diverse role models. Such acts can indicate that traditionally excluded learners will not only be welcomed in the course space, but that they can also see themselves in successful careers in that field.

Intended outcomes of your efforts

As you consider changes to your course, what outcomes are you hoping for? These could include that:

- Everybody from a traditionally excluded group would be able to achieve a comparable outcome.

- People’s feelings about the quality of their learning (ability to learn, career readiness) would be comparable.

- People’s feelings about their classroom experience (feelings of inclusion, connectedness).

Take a few minutes and write down your own intentions or intended outcomes.

Once you have made the changes to your own course, what will you see or hear differently?

How will you know that you have accomplished those outcomes?

Some definitions

The removal of systemic barriers and biases enabling all individuals to have equal opportunity to access and benefit from the program.

sshrc-crsh.gc.ca/funding-financement/nfrf-fnfr/edi-eng.aspx

Differences in race, colour, place of origin, religion, immigrant and newcomer status, ethnic origin, ability, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, gender expression and age.

sshrc-crsh.gc.ca/funding-financement/nfrf-fnfr/edi-eng.aspx

The practice of ensuring that all individuals are valued and respected for their contributions and equally supported.

sshrc-crsh.gc.ca/funding-financement/nfrf-fnfr/edi-eng.aspx