3 Academic accommodations

In this chapter, you’ll:

- Identify reasons why accommodations are critical for inclusive learning, including for disabilities and compassion

- Identify and implement approved academic accommodations

- Decide what other accommodations or flexibility you wish to offer in your courses

Academic accommodations (e.g., exams, classes)

Models of academic learning are informed by stereotypes we have learned from a variety of sources. From the instructor’s perspective, a stereotypical view might be that students should learn material exactly the way it is taught, and that student successes in lectures, lab courses, or discussion groups reflect the work they put into their studies.

Yet, many students face persistent barriers to their learning that are consequences of cognitive, physical, mental health, or other issues. These barriers are common (e.g., 46% of students in universities and colleges in North America contend with depression; Ontario Universities, 2021), and many students in every course are likely trying to overcome one or more of these barriers to their learning and in their lives outside academics.

Academic accommodations support a student’s efforts to work around barriers to achieve the learning objectives of a course. Accommodation does not imply compromise or dilution of course expectations. Standards do not become lower because a thoughtful instructor supported a student’s academic accommodation. Rather, accommodation is more like supporting students in finding a different pathway to the end result or learning outcome.

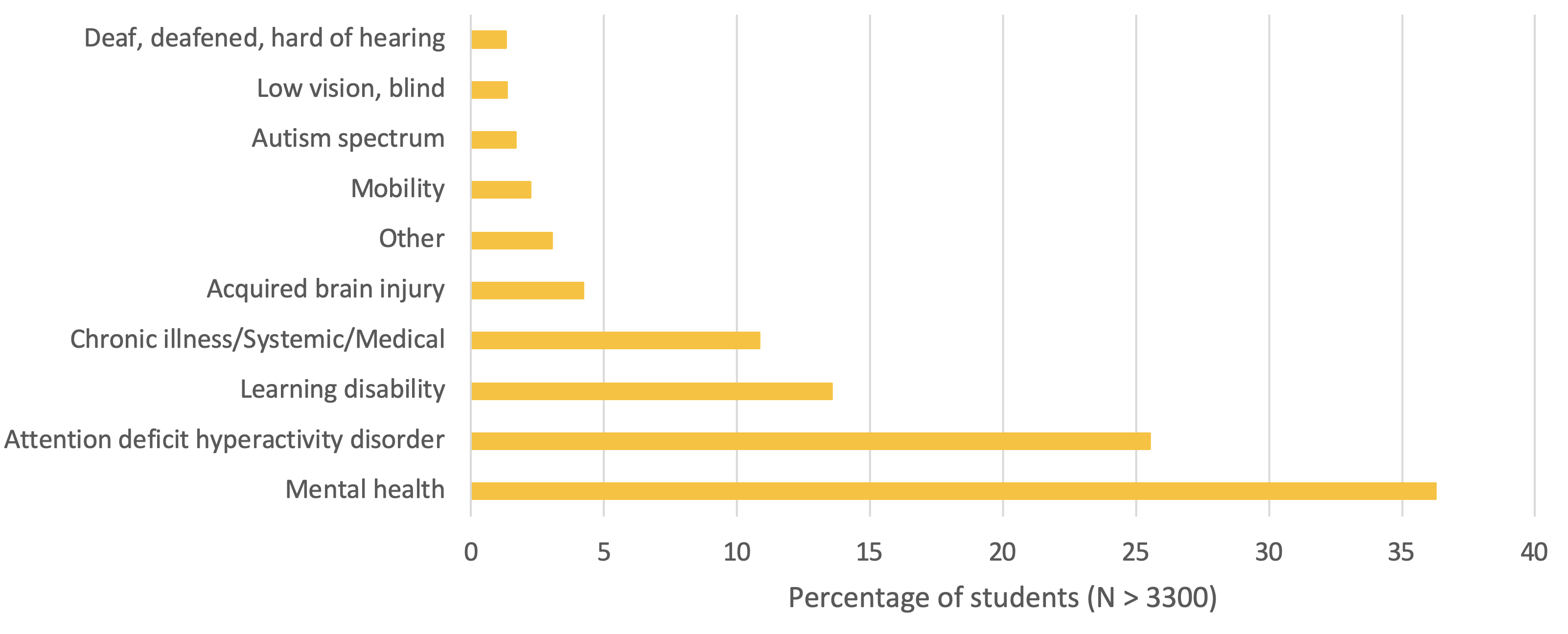

Accommodations are needed for a variety of reasons. Many academic accommodations can be required by law or regulation, as in Ontario through its Human Rights Code. Here are recent data from students at uOttawa (2021) that summarize common reasons for approved accommodations:

As professors, we do not have a right to know the specific reason for the accommodation; rather, we have access to the nature of the approved accommodation itself. Accommodations are varied and tailored to the situation and can include additional time on exams, large-sized paper, digital exams, etc.

Most institutions have a centralized process to review and approve/decline students’ requests for exam accommodations for students who have disabilities that may be temporary or permanent, visible or invisible. The goal of these accommodations is to allow “an equitable opportunity to fully access and participate in the learning environment with dignity, autonomy and without impediment while preserving academic freedom, academic integrity, and academic standards.”

As educators, we are “responsible for collaborating in the academic accommodation process and for implementing the approved accommodation plan, as applicable:

- referring all accommodation requests related to a disability to your university’s Academic Accommodations Service.

- be alert to the possibility that a person may need an accommodation even if they have not made a specific or formal request.

- implementing the accommodation plan with the support of Academic Accommodations staff and their faculty, and participating where appropriate in the development of accommodation plans;

- working collaboratively with Academic Accommodations, the student, and the Faculty to find a satisfactory resolution in those instances where the educator believes that an accommodation plan puts at risk the student’s ability to meet academic standard, academic integrity, essential academic requirements and skills; and

- in collaboration with the Teaching and Learning Support Service [or other Centre for University Teaching], consider universal design elements of their course that could minimize the need for accommodations.”

If a particular accommodation does not seem appropriate, you can discuss further with the student and/or Academic Accommodations. For example, a student may have an accommodation that seems counter to the learning outcome itself. In that case, a different accommodation may be more appropriate. See uOttawa’s Quick Guide.

The process at uOttawa

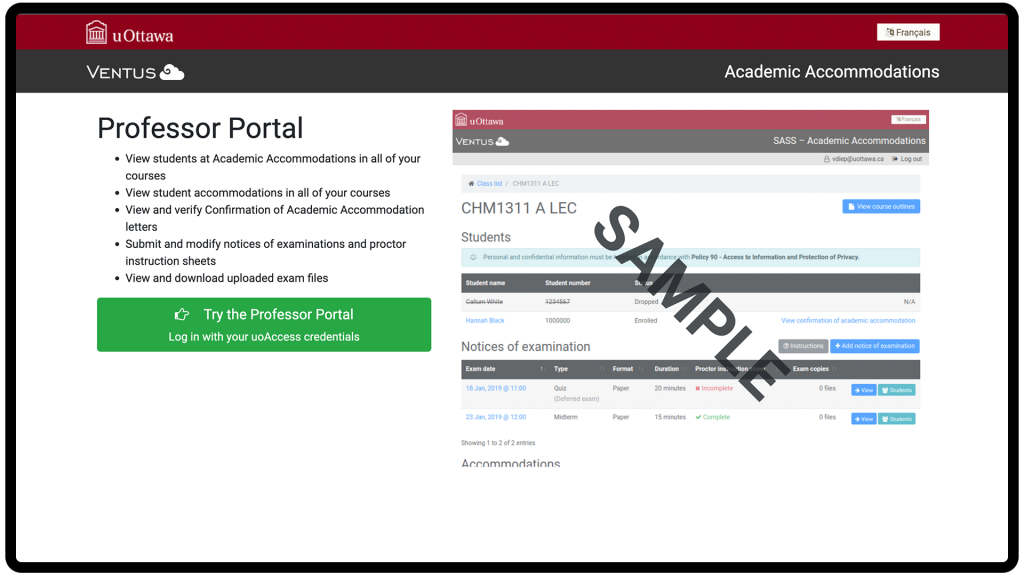

Before your courses starts and periodically during your course, log in to the Ventus Professor Portal to:

- Check the list of accommodations approved for students in your courses; some may involve accommodations during classes (e.g., note-taking, recording, access to slides) or assessment (e.g., time extensions, memory aid, low auditory distractions)

- Submit Notices of Examination (NOE) (deadline is 10 calendar days before the exam!); The Academic Accommodations service will arrange for proctoring exams for students with many accommodations

- Delete and modify NOEs already submitted

- Fill out / edit Proctor Instruction sheets

- Check which students have confirmed to write the exam at SASS – Academic Accommodations (with accommodations) or in-class (without accommodation)

- Send a copy of your exam to your academic unit before the deadline. This step allows for exams to be organized and processed if necessary; for example, the exam may be enlarged for students who have low vision.

- If students have written an exam with Academic Accommodations, their exam will be delivered to your Department shortly after the exam

Beyond the regulations

Consider adding a statement to your syllabus that tells students that you adhere to the approved accommodations and that they can approach you if desired with questions or concerns. Students are often not aware that they can request accommodations or that educators do have a responsibility to accommodate – a message in the syllabus can help open the lines of communication.

You can also decide if you will allow other kinds of accommodations. For example, while time extensions for exams are typically granted for students with certain kinds of approved disabilities, a parent writing a take-home exam with young children home does not “fit” into a pre-determined category. Depending on the type of assessment, you might choose to work with the student to identify an accommodation to enable them to demonstrate the extent of their knowledge. An alternate path might be as simple as a time extension.

Decisions beyond the required accommodations are in your hands, based on the course, students, and assessment context. Inclusive practices in teaching can go far beyond the minimum standard. The above example shows just one type of opportunity that we can take as educators.