2 What is Humanizing Learning?

When students were asked what “humanizing learning” means to them, one replied:

“When instructors see us as people – unique, with different hopes and different stresses – and treat us as more than a number.”

Another student said that the meaning of humanized learning depended on the definition of humanize. Humanize can mean “to uphold a particular view or value of what it means to be human, and furthermore to find ways to act on this concern. Such concerns also need to be practically translated into the more experiential issues of what practices can make people feel more human.”[1] So, humanized learning could mean prioritizing this concern for the human-as-person and adopting practices that may increase feelings of humanity in education. Humanistic approaches to teaching and learning can also be defined as “the development of the whole person through the acquisition of knowledge, skills, competencies, ethics and habits of mind. Ultimately, the result of a humanistic-oriented educational process is that it fosters personal agency, is trauma-informed, and is inclusive, such that students can apply their knowledge and skills creatively in any situation.”[2] Another, expanded definition of humanizing learning is given by Pacansky-Brock,[3] who emphasizes the importance of creating positive connections between the student and the instructor:

“Humanizing leverages learning science and culturally responsive teaching to create an inclusive, equitable online class climate for today’s diverse students. When you teach online, it is easy to relate to your students simply as names on a screen. But your students are much more than that. They are capable, resilient humans who bring an array of perspectives and knowledge to your class. They also bring life experiences shaped by racism, poverty, and social marginalization. In humanized online courses, positive instructor-student relationships are prioritized and serve ‘as the connective tissue between students, engagement, and rigor’… In any learning modality, human connection is the antidote for the emotional disruption that prevents many students from performing to their full potential and in online courses, creating that connection is even more important.”

There is of course a potential tension in the quote above. Resiliency and rigour may work in opposition to an inclusive framing of humanized learning if they are not well defined as systemic concerns.

Online learning can also be humanized, although some of the considerations for how to do this well are different from the in-person context.[4] But it can include the creation of more inclusive online learning environments, partly by “considering structural issues of power and privilege that produce and constrain pedagogical possibilities.”[5]

With online learning, as with the in-person context, instructors can create a more inclusive environment by practicing an ethic or pedagogy of care. This is a “method and practice of teaching where the instructor takes the role of care-giver and students take on the role of care-receiver. Caring is relational and includes concern for person and performance.”[6] The instructor can approach and value students firstly as humans, with their own experiences, positionality, and perspectives, not merely as names on a course list. It is important here to draw attention to the idea that ‘care-giving’ is reciprocal, with students also caring for instructors. Learning that takes place in a warm responsive environment is caring. Being responsive to the needs of students in a particular class is caring. We want to highlight here that even in classes with many students (such as first- and second-year classes), that these steps can still be taken. It may be daunting for a professor to take on the role of care-giver to 500 students, but there are ways to ease this transition and create a positive environment.

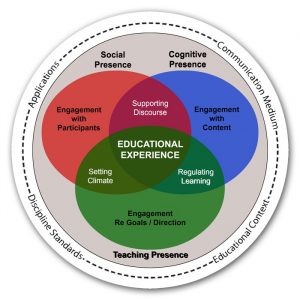

Three important elements of humanizing an online learning experience can be found in the Community of Inquiry (CoI) framework.

CoI is “a theoretical framework that situates learning within a group of learners and is based upon the premise that learning is inherently social, and that learning is supported through three distinct presences: social, teaching, and cognitive.”[7] (see also [8]; [9]). Let’s have a quick look at the framework’s “three presences,” as discussed by Palahicky and colleagues.[10] Social presence refers to the communication, interpersonal relationships, and sense of community within a learning environment, such as an online course.[11] It is “the socially mediated, interpersonal aspect of learning” that shapes how learners interact with the course material, their peers, and the instructor.[12] Cognitive presence is “the extent to which learners are able to construct and confirm meaning through sustained reflection and discourse.” That is, how the course can become a meaningfully reflective and collaborative learning experience for students.[13] And finally, teaching presence is “the design, facilitation, and direction of cognitive and social processes for the purpose of realizing personally meaningful and educationally worthwhile learning outcomes.”[14] It is developed in the design of curriculum and activities, as well as in the facilitation of discussions. Together, these interconnected elements offer a the “big picture” of what the humanizing learning approach can involve, both in-person and online.

What Humanizing Learning Is Not

When asked to describe what they consider to be the opposite of humanizing learning, some students replied:

“When instructors mispronounce your name or don’t know it at all.”

“A course where I’m really just doing everything to get a grade – not really caring about a bigger picture, if there is one.”

“When instructors are unable to understand the challenges and realities of life experienced by students outside of the classroom. We are human beings with financial, care-giving, social and life responsibilities. An educator shouldn’t add to the already long list of barriers to education”.

“When I face huge academic deductions/punishments/consequences for genuine, human accidents.”

What is Sometimes Mistaken for Humanizing Learning?

Humanizing learning is not meant to be a predetermined set of rules or tasks that an instructor must follow. Instead, it is an approach to teaching and learning which benefits instructors and students alike. For example, as Watson[15] observed about the humanizing approach of “trauma-informed teaching” in the K-12 context, it “is not a curriculum, set of prescribed strategies, or something you need to ‘add to your plate’. It’s more like an empathic lens through which you [i.e., the instructor] choose to view your students which will help you build better relationships, prevent conflict, and teach them effectively.” Denial[16] made a similar observation about kindness as a pedagogical practice:

“[Kindness] is not about sacrificing myself, or about taking on more emotional labor. It has simplified my teaching, not complicated it, and it’s not about niceness. Direct, honest conversations, for instance, are often tough, not nice. But the kindness offered by honesty challenges both myself and my students to grow. As bell hooks memorably wrote in Teaching to Transgress, ‘there can be, and usually is, some degree of pain involved in giving up old ways of thinking and knowing and learning new approaches.’”

In other words, practicing kindness, trauma-informed teaching, and other aspects of humanization aren’t “chores” that an instructor has to take on. Instead, they are new approaches to thinking about and planning interactions with students, and about teaching and learning online. They are integral to dismantling oppressive, colonial, heteropatriarchal, and ableist systems. The humanizing approach fundamentally challenges staid ways of engaging in education in which students are receptive and instructors are directive.

Why is Humanizing Learning Important?

The humanized approach to learning is connected with and aware of students’ well-being. While the mental health and well-being of students have always been important, both have become major issues for educators and learning institutions during the COVID-19 pandemic. Many students feel isolated or alienated because of online coursework and limited social interaction. Online learners have reported feeling isolated and disconnected from their studies, suggesting a need for instructors to facilitate a better sense of connection between a individual students and their online community.[17] Creating a supportive, engaging online learning environment through enhanced teacher presence helps to limit the negative impacts of isolation, technological challenges, and the pressures of schoolwork and life in general.[18] The “social presence” aspect of humanized learning is an important motivational factor in students’ learning process [19],[20]. As Denial[21] writes, practicing a humanized pedagogy of kindness that “placed the common humanity of students, faculty, and staff at its core” helped to address instructor concerns and challenges during the pandemic, including concerns about students, safety, and well-being. Supported, motivated, engaged, and connected students will experience improved well-being and are less likely to be negatively impacted by the challenges and pressures that online education–not to mention life in general–may present.

Humanizing learning can also influence student engagement, motivation, and academic achievement. It’s well established that student performance in online courses is related to “student interaction and sense of presence” within the course.[22] Reyes and colleagues[23] observed that fostering positive emotional connections and interactions in the classroom helps to promote student academic achievement. The quality of interpersonal interaction in a course “relates positively and significantly to student grades,” which are a major indicator of academic achievement.[24] In a study on undergraduate psychology students enrolled in required statistics courses, Waples[25] found that establishing emotional bonds and relationships between students and their instructor promoted academic achievement. Keeling[26] similarly connected an “ethic of care” on the part of instructors with student success. Applying a humanizing approach to courses has a positive impact on students’ performance and on their potential academic achievements.

Humanizing learning can positively transform student experiences, improve the culture of academic institutions, and reverberate in our broader communities as well. As students move beyond higher education , they can make use of and model critical skills and approaches learned from the humanizing approach. As well as teaching important work and life skills, humanizing can also improve the culture of societal institutions , particularly the culture of colleges and universities. The academic institution can become “a place of caring, support and the meaningful pursuit of academic and professional goals… [through focusing on] the physical, psychological and social well-being and safety of students and professors.”[27] Practicing humanizing strategies such as “feminist kindness” can have a positive impact on “shaping power relations within classrooms and institutions.”[28] Culturally-responsive teaching is another humanizing element with important influence on how the institution understands and relates to learners of different ethnic groups and cultures; for example, in implementing equity initiatives.[29] The culture of the college or university, as well as students’ work and lives in the community outside of higher education, are all improved through the use of humanizing approaches and strategies.

- Galvin, K. & Todres, L. (2013). Caring and Well-being: A Lifeworld Approach. Routledge. ↵

- Blessinger, P., Sengupta, E. & Reshef, S. (2019). Humanising higher education via inclusive leadership. University World News. Retrieved from https://www.universityworldnews.com/post.php?story=20190218081816874. ↵

- Pacansky-Brock, M. (2020). How to humanize your online class, version 2.0 [Infographic]. Retrieved from https://brocansky.com/humanizing/infographic2. ↵

- Estes, J. S. (2015). Moving Beyond a Focus on Delivery Modes to Teaching Pedagogy. In J. Keengwe, J. Mbae, & S. Ngigi (Eds.), Promoting Global Literacy Skills through Technology-Infused Teaching and Learning (pp. 86-101). IGI Global. https://doi-org.myaccess.library.utoronto.ca/10.4018/978-1-4666-6347-3.ch005 ↵

- Mehta, R., & Aguilera, E. (2020). A critical approach to humanizing pedagogies in online teaching and learning. International Journal of Information and Learning Technology, 37(3), 109-120. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJILT-10-2019-0099. ↵

- Palahicky, S., DesBiens, D., Jeffery, K., & Webster, K.S. (2019). Pedagogical Values in Online and Blended Learning Environments in Higher Education. In Keengwe, J. (Ed.), Handbook of Research on Blended Learning Pedagogies and Professional Development in Higher Education (pp. 79-101). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-5225-5557-5.ch005. ↵

- Palahicky, S., DesBiens, D., Jeffery, K., & Webster, K.S. (2019). Pedagogical Values in Online and Blended Learning Environments in Higher Education. In Keengwe, J. (Ed.), Handbook of Research on Blended Learning Pedagogies and Professional Development in Higher Education (pp. 79-101). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-5225-5557-5.ch005. ↵

- Conrad, O. (2015). Community of Inquiry and Video in Higher Education: Engaging Students Online (ED556456). ERIC. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED556456.pdf. ↵

- Oyarzun, B.A. & Morrison, G.R. (2013). Cooperative Learning Effects on Achievement and Community of Inquiry in Online Education. Quarterly Review of Distance Education, 14(4), 181-194, 255. ↵

- Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (2000). Critical inquiry in a text-based environment: Computer conferencing in higher education model. The Internet and Higher Education, 2(2-3), 87-105. ↵

- Garrison, D.R. (2009). Communities of Inquiry in Online Learning. In Rogers, P., Berg, G., Boettcher, J., Howard, C., Justice, L., & Schenk, K. (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Distance Learning, Second Edition (pp. 352-355). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-60566-198-8.ch052. ↵

- Palahicky, S., DesBiens, D., Jeffery, K., & Webster, K.S. (2019). Pedagogical Values in Online and Blended Learning Environments in Higher Education. In Keengwe, J. (Ed.), Handbook of Research on Blended Learning Pedagogies and Professional Development in Higher Education (pp. 79-101). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-5225-5557-5.ch005. ↵

- Garrison, D.R., Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (2001). Critical thinking, cognitive presence, and computer conferencing in distance education. American Journal of Distance Education, 15(1), 7-23. ↵

- Anderson, T., Rourke, L., Garrison, D.R., & Archer, W. (2001). Assessing Teaching Presence in a Computer Conference Environment. Journal of asynchronous learning networks, 5(2), 1-17. ↵

- Watson, A. (2018). A crash course on trauma-informed teaching. Truth for Teachers. Retrieved from https://truthforteachers.com/truth-for-teachers-podcast/trauma-informed-teaching/. ↵

- Denial, C.J. (2019). A Pedagogy of Kindness. Hybrid Pedagogy. Retrieved from https://hybridpedagogy.org/pedagogy-of-kindness/. ↵

- Muir, T., Douglas, T., & Trimble, A. (2020). Facilitation strategies for enhancing the learning and engagement of online students. Journal of University Teaching & Learning Practice, 17(3). ↵

- Stone, C. & Springer, M. (2019). Interactivity, Connectedness and ‘Teacher-Presence’: Engaging and Retaining Students Online. Australian Journal of Adult Learning, 59(2), 146-169. ↵

- Yamada, M. (2009). The role of social presence in learner-centered communicative language learning using synchronous computer-mediated communication: Experimental study. Computers & Education, 52(4), 820–833. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2008.12.007. ↵

- Yamada, M. (2009). The role of social presence in learner-centered communicative language learning using synchronous computer-mediated communication: Experimental study. Computers & Education, 52(4), 820–833. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2008.12.007. ↵

- Denial, C.J. (2021). Feminism, Pedagogy, and a Pandemic. Journal of Women's History, 33(1), 134-139. https://doi.org/10.1353/jowh.2021.0006. ↵

- Picciano, A. (2002). Beyond student perceptions: Issues of interaction, presence, and performance in an online course. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 6(1), 21-40. ↵

- Reyes, M.R., Brackett, M.A., Rivers, S.E., White, M., & Salovey, P. (2012). Classroom Emotional Climate, Student Engagement, and Academic Achievement. Journal of Educational Psychology. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027268. ↵

- Jaggars, S.S. & Xu, D. (2016). How do online course design features influence student performance? Computers & Education, 95, 270-284. ↵

- Waples, J.A. (2016). Building emotional rapport with students in statistics courses. Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Psychology, 2(4), 285-293. ↵

- Keeling, R. (2014). An Ethic of Care in Higher Education: Well-Being and Learning. Journal of College and Character, 15, 141-148. ↵

- Blessinger, P., Sengupta, E. & Reshef, S. (2019). Humanising higher education via inclusive leadership. University World News. Retrieved from https://www.universityworldnews.com/post.php?story=20190218081816874. ↵

- Magnet, S., Mason, C., & Trevenen, K. (2014). Feminism, Pedagogy, and the Politics of Kindness. Feminist Teacher, 25(1), 1-22. https://doi.org/10.5406/femteacher.25.1.0001. ↵

- https://www.facultyfocus.com/articles/equality-inclusion-and-diversity/five-essential-strategies-to-embrace-culturally-responsive-teaching/ ↵