4.4 Job Design

Job design pertains to the specification of contents, methods, and relationship of jobs in order to satisfy technological and organizational requirements as well as the social and personal requirements of the job holder. Through job design, organizations can measure and raise productivity levels of employees and employee job morale and satisfaction. Although job analysis, as just described, is important for an understanding of existing jobs, organizations must also adapt to changes in workflow and organizational demands and consider whether jobs need to be redesigned. When an organization is changing or expanding, human resource professionals must also help plan for new jobs and shape them accordingly.

Productivity Competencies

- Develop potential initiatives that align culture and values with organizational strategy.

- Measure employee productivity.

- Measure employee engagement and morale.

Source: HRPA Professional Competency Framework (2014), pg. 12. © HRPA, all rights reserved.

These situations call for job design and business process re-engineering (BPE / BPR), the process of defining the way work will be performed and the tasks that a given job requires. Job redesign is a similar process that involves changing an existing job design. To design jobs effectively, a person must thoroughly understand the job itself (through job analysis) and its place in the larger work unit’s work flow process. Having a detailed knowledge of the tasks performed in the work unit and in the job gives the manager many alternative ways to design a job.

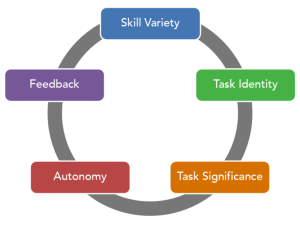

Designing Efficient Jobs: Job Characteristics Model

The job characteristics model is one of the most influential attempts to design jobs with increased motivational properties (Hackman & Oldham, 1975). The model describes five core job characteristics leading to critical psychological states, resulting in work-related outcomes.

Skill Variety refers to the extent to which the job requires a person to utilize multiple skills. A car wash employee whose job consists of directing customers into the automated car wash demonstrates low levels of skill variety, whereas a car wash employee who acts as a cashier, maintains car wash equipment, and manages the inventory of chemicals demonstrates high skill variety.

Task Identity refers to the degree to which a person is in charge of completing an identifiable piece of work from start to finish. A web designer who designs parts of a website will have low task identity, because the work blends in with other Web designers’ work; in the end it will be hard for any one person to claim responsibility for the final output. The webmaster who designs an entire web site will have high task identity.

Task Significance refers to whether a person’s job substantially affects other people’s work, health, or well-being. A janitor who cleans the floors at an office building may find the job low in significance, thinking it is not a very important job. However, janitors cleaning the floors at a hospital may see their role as essential in helping patients get better. When they feel that their tasks are significant, employees tend to feel that they have an impact on their environment, and their feelings of self-worth are boosted (Grant, 2008).

Autonomy is the degree to which a person has the freedom to decide how to perform his or her tasks. For example, an instructor who is required to follow a predetermined textbook, covering a given list of topics using a specified list of classroom activities, has low autonomy. On the other hand, an instructor who is free to choose the textbook, design the course content, and use any relevant materials when delivering lectures has higher levels of autonomy. Autonomy increases motivation at work, and it also has other benefits. Giving employees autonomy at work is a key to individual and company success, because autonomous employees are free to choose how to do their jobs and therefore can be more effective. They are also less likely to adopt a “this is not my job” approach to their work environment and instead be proactive (do what needs to be done without waiting to be told what to do) and creative (Morgeson et al., 2005). The consequence of this resourcefulness can be higher company performance.

Feedback refers to the degree to which people learn how effective they are being at work. Feedback at work may come from other people, such as supervisors, peers, subordinates, and customers, or it may come from the job itself. A salesperson who gives presentations to potential clients but is not informed of the clients’ decisions, has low feedback at work. If this person receives notification that a sale was made based on the presentation, feedback will be high. The relationship between feedback and job performance is more controversial. In other words, the mere presence of feedback is not sufficient for employees to feel motivated to perform better. In fact, a review of this literature shows that in about one-third of the cases, feedback was detrimental to performance (Kluger & DeNisi, 1996). In addition to whether feedback is present, the sign of feedback (positive or negative), whether the person is ready to receive the feedback, and the manner in which feedback is given will all determine whether employees feel motivated or demotivated as a result of feedback.

According to the job characteristics model, the presence of these five core job dimensions leads employees to experience three psychological states: They view their work as meaningful, they feel responsible for the outcomes, and they acquire knowledge of results. These three psychological states in turn are related to positive outcomes such as overall job satisfaction, internal motivation, higher performance, and lower absenteeism and turnover (Humphrey et al., 2007; Johns et al., 1992).

Note that the five job characteristics are not objective features of a job. Two employees working in the same job may have very different perceptions regarding how much skill variety, task identity, task significance, autonomy, or feedback the job affords. In other words, motivating potential is in the eye of the beholder. This is both good and bad news. The bad news is that even though a manager may design a job that is supposed to motivate employees, some employees may not find the job to be motivational. The good news is that sometimes it is possible to increase employee motivation by helping employees change their perspectives about the job. For example, employees laying bricks at a construction site may feel their jobs are low in significance, but by pointing out that they are building a home for others, their perceptions about their job may be changed.

“4.4 Job Design” from Human Resources Management – 3rd Edition by Debra Patterson is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.