Section 3: Knowledge Translation/Mobilization Strategies

Dr. Karen A. Patte; Jayne Morrish; and Megan Magier

Section Overview

In this section, you will learn about KTE/KMb strategies, which are the “how” or the “doing” part of KTE/KMb. How will you mobilize/translate your research/findings? How will you engage with people to mobilize/translate the knowledge that you have? This section provides a high-level overview of what KTE/KMb strategies are and includes resources to support you in actually carrying out KTE/KMb.

Section Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain key KTE/KMb strategies;

- Understand the importance of knowledge exchange in the KTE/KMb strategy process;

- Access relevant resources to support your own development of KTE/KMb strategies;

- Understand the importance of and how to use plain language communication; and

- Understand some of the relevant equity, diversity, and inclusion considerations when developing KTE/KMb strategies.

Test Your Knowledge

Complete the following activity to assess how much you already know about the content that will be covered in this section.

CASE STUDY: Engaging With Youth to Create Meaningful KMb Materials of Mental Health Research

How can all of the abovementioned lessons about KTE/KMb come together to form meaningful and accurate engagement around research knowledge? How can a researcher or a team be sure that they are selecting KTE/KMb strategies that are relevant, accessible and equitable for their audiences – with context being considered? This case study explores how one national research project has intentionally engaged with their audience and context experts to ensure that their KTE/KMb is centred around how, why and what their knowledge users want to see around research findings.

The COMPASS study is a national initiative headquartered at the University of Waterloo. Since its inception in 2012, COMPASS researchers have been collecting health information from about 65,000 Grade 9 to 12 students attending more than 130 secondary schools in Ontario, Alberta, Quebec, and British Columbia. The Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) and Health Canada are funding the research. One component of the COMPASS study is the mental health section, which explores youth mental health and the impact of school programs and resources, and relationships with various behaviours such as physical activity, substance use, sleeping, eating behaviours, bullying/aggression, peer and familial relationships, and screen time.

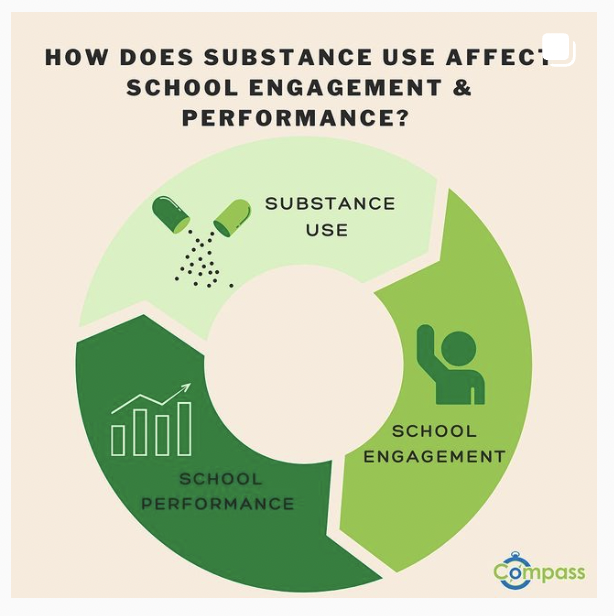

The team overseeing the mental health section of the COMPASS study continually focuses on ensuring that they are providing their data and results to other researchers as well as broader knowledge user groups such as schools, public health, community organizations, and policy makers. However, the team realized that there was a gap in their KTE/KMb work in that they were not always reaching youth themselves. Looking to the above outlined lessons on the importance of equitable exchange with knowledge users, the team formed the COMPASS Youth Knowledge Mobilization Leaders committee, composed of youth from the age groups that participate in COMPASS. This committee meets regularly (either bi-weekly or monthly) to learn more about COMPASS study findings and strategize ways of sharing results that are engaging and relevant for youth. The committee is entirely youth-led, in that the youth members set the agenda, select research findings that they feel are most relevant for youth, and develop the KTE/KMb tools to share the information in ways likely to be engaging for youth. At the current point in time, the committee is mainly focused on sharing results via social media, having selected Instagram as the platform where youth would want to learn about research, but this may expand in the future.

What is so impactful about COMPASS’ youth-led KTE/KMb work is that youth are not only at the table informing KTE/KMb for their peers, but they also have an active and respected voice in the decision-making and creation for KTE/KMb plans/materials for the project. As mentioned earlier within this chapter (and will be outlined more later in this section), KTE/KMb work should be based on how and why individuals want to and can access information. The most equitable way to accomplish that is via authentically engaging with context experts around KTE/KMb planning. In the case of the COMPASS Youth Knowledge Mobilization Leaders committee, the youth-members are looked to for their knowledge of the type of information that youth would want to know about from the research findings, as well as the ways in which youth would want to have that information presented to them, and how the team can best engage with broader groups of youth. Moreover, the entire process is underpinned by full respect of the youth’s time and expertise, with all members being paid for their time contributed to the project, being offered time to practice leadership skills, and being provided tangible professional experiences to lend to their own resumes.

As the team moves forward they will continue to lead youth-focused KTE/KMb, as well as translate all posts so that the work is bi-lingual and reaches Francophone youth. The broader COMPASS team is also focusing on training researchers on equitable youth engagement principles and practices to inform future COMPASS KTE/KMb work. To learn more about the COMPASS Youth Knowledge Mobilization Leaders committee, please see this Brock News article.

Below are some samples of the COMPASS Youth Knowledge Mobilization Leaders’ Instagram posts (check out the English and French Instagram accounts).

Planning KTE/KMb Strategies

From the previous sections, it is clear that there is a need for KTE/KMb and that this work should be based on how and why knowledge users engage with knowledge, as well as recognizing the value in the different types of knowledge that knowledge users may bring to the KTE/KMb process (e.g., context and content experts). The question that arises now is how can individuals/teams effectively mobilize/translate their research/findings? The “how” of KTE/KMb is accomplished through what are commonly called KTE/KMb strategies.

Next, we will review different examples of and resources for KTE/KMb strategies. Please note that this is not an exhaustive list. Some research from the health care field has indicated that “so called “multifaceted” or complex interventions are more effective than “single” or simple interventions” (Kitson & Harvey, 2016, p. 295) in facilitating knowledge into policy and practice. That is, a single KTE/KMb strategy alone may not be enough to produce a meaningful and long-lasting impact.

Keep in mind when reviewing this section that KTE/KMb strategies should always be carefully selected based on the knowledge at hand, what is relevant to your knowledge users, and how your knowledge users actually access information. As noted above, KTE/KMb strategies should ideally involve some level of authentic exchange and engagement; consider what knowledge and information they have to contribute to the process. You should never select a KTE/KMb strategy because it is easy or popular; you need to mobilize/translate with and for your knowledge users. As we have learned, KTE/KMb is not a one-size fits all or unidirectional process; it is a collaborative process that should be unique to each team/project.

Examples and Resources

Research Summaries/Plain Language Summaries

Gudi et al. (2021) define a plain language summary as a “synopsis of research findings written in an easily understandable way, so that even a lay audience would grasp the content” (p.1). As stated by Phipps and colleagues (2013), “research summaries come in many forms, including press releases, policy briefs, clinical practice guidelines, research fact sheets, knowledge briefs, and structured abstracts” (p. 3), and are documents that summarize research findings and potential implications in clear and concise ways, using plain language and clear examples (e.g., are written for non-academic audiences). There is some research indicating that research summaries may be effective tools for KTE/KMb work (Bredbenner & Simon, 2019), but the research is limited. Also, it is important to note that most academics/researchers do not have training in writing for non-academic audiences.

Deeper Dive

Please see this article by Gudi et al. (2021) on the role of plain language summaries in KTE/KMb:

- Gudi, S. K., Tiwari, K. K., & Panjwani, K. (2021). Plain‐language summaries: An essential component to promote knowledge translation. International Journal of Clinical Practice, 75(6), e14140.

Please also see this article by Phipps and colleagues (2013) on the development of clear language research summaries for more information and background on this type of KTE/KMb work:

- Phipps, D., Jensen, K., Johnny, M., & Myers, G. (2013). A field note describing the development and dissemination of clear language research summaries for university-based knowledge mobilization. Scholarly and Research Communication, 4(1). https://src-online.ca/index.php/src/article/view/44

Infographics

Short for “information graphics”, infographics simply refers to visual/graphical depictions of information. Infographics generally exist on the age-old concept that “a picture is worth a thousand words”, and that humans have used images to display information/tell stories from even early cave paintings (Lankow, et al., 2012; Smiciklas, 2012). The process of creating infographics has been broadly referred to as data visualization (Smiciklas, 2012). Research has shown that infographics can generally help to explain and present complex information to external/broader groups (Smiciklas, 2012). In general, infographics’ purpose is to “capture users’ attention, help them better understand the information presented, increase their ability to retain and recall the message, and encourage them to act in accordance with the information” (Mc Sween-Cadieux et al., 2021, p. 2). There have been numerous empirical studies of the use of infographics in the KTE/KMb field, and while no broader scoping review has been conducted, Mc Sween-Cadieux and colleagues (2021) state that that type of review is currently being undertaken and should be available in the future. In a study by Provvidenza and colleagues (2019) of the role of infographics in KTE/KMb around concussion education, students, teachers, and health care professionals reported that the infographics provided new knowledge and they intended to use them to educate others, but also that developing infographics collaboratively to appeal to different audiences and to share lived experiences of individuals with concussions would further enhance the impact.

There are numerous software options available to help support the creation of infographics, one excellent resource to start with is Information is Beautiful.

Deeper Dive

To take a deeper dive into infographics, below are some additional resources with further information on infographics:

- Lankow, J., Ritchie, J., & Crooks, R. (2012). Infographics: The power of visual storytelling. John Wiley & Sons.

- Mc Sween-Cadieux, E., Chabot, C., Fillol, A., Saha, T., & Dagenais, C. (2021). Use of infographics as a health-related knowledge translation tool: Protocol for a scoping review. BMJ Open, 11(6), e046117.

- Provvidenza, C. F., Hartman, L. R., Carmichael, J., & Reed, N. (2019). Does a picture speak louder than words? The role of infographics as a concussion education strategy. Journal of Visual Communication in Medicine, 42(3), 102-113.

- Smiciklas, M. (2012). The power of infographics: Using pictures to communicate and connect with your audiences. Que Publishing.

Graphical Abstracts

According to Elsevier (n.d.):

Journals are increasingly requesting the submission of a “graphical” or “visual abstract” alongside the body of the article. This is a single, concise, pictorial and visual summary of the main findings of the article. It could either be the concluding figure from the article or better still a figure that is specially designed for the purpose, which captures the content of the article for readers at a single glance. (para. 1)

Research has shown that graphical abstracts may be effective at mobilizing/translating health care-focused research, particularly when disseminated via social media (Ibrahim et al., 2017; Chapman et al., 2019).

Deeper Dive

Please see this resource by Elsevier (n.d.) to take a deeper dive on graphical abstracts, how to create them, and examples:

Social Media

Social media is a very broad type of KTE/KMb strategy, as there are numerous platforms and ways in which those platforms can be used. As noted by Phipps (2011), “social media can theoretically support a co-creation KMb method where researchers and their decision-maker partners go beyond exchanging knowledge to co-create knowledge” (p. 7), as it may allow for broader networking, engagement, and sharing across context and content experts. Reibling (2015) has outlined numerous recommendations for the effective use of social media in KTE/KMb work, including integrating social media throughout the research process, questions to consider for social media (e.g., “do I need an online presence” (p. 11)), considering your social identity, and considering your audience.

Deeper Dive

Please see this presentation by Reibling (2015) to take a deeper dive on the role of social media in KTE/KMb:

- Reibling, S. (2015). Effective use of social media for knowledge mobilization [Presentation]. Knowledge Mobilization Institute Summer School 2015. https://www.slideshare.net/sreibling/reibling-effective-use-of-social-media-for-knowledge-mobilization

Here are some examples of KTE/KMb based social media accounts:

Arts-Based KTE/KMb

According to Kukkonen and Cooper (2019):

Arts-based knowledge translation (ABKT) is a process that uses diverse art genres (e.g., visual arts, performing arts, creative writing, multimedia including video and photography) to communicate research with the goal of catalyzing dialogue, awareness, engagement, and advocacy to provide a foundation for social change on important societal issues. (p. 293)

In general, the UNESCO document Imagining the Future of Knowledge Mobilization: Perspectives from UNESCO Chairs by Hewitt (2021) outlines several ABKT projects from across the globe, including using artwork to discuss the issue of poverty among homeless/street-involved women (p.72) and participatory videos for storytelling and action in Brazil (p. 74). Kukkonen and Cooper (2019) outline a four-stage planning framework for ABKT work of “(1) setting goals of ABKT by target audiences; (2) choosing art form, medium, dissemination strategies, and methods for collecting impact data; (3) building partnerships for co-production; and (4) assessing impact” (p. 293).

Deeper Dive

To take a deeper dive into AKBT, below are some additional resources with further information:

- Hewitt, T. (2021). Imagining the future of knowledge mobilization: Perspectives from UNESCO Chairs. Canadian Commission for UNESCO. https://en.ccunesco.ca/-/media/Files/Unesco/Resources/2021/01/ImaginingFutureOfKnowledgeMobilization.pdf

- Kukkonen, T., & Cooper, A. (2019). An arts-based knowledge translation (ABKT) planning framework for researchers. Evidence & Policy: A Journal of Research, Debate and Practice, 15(2), 293-311.

Policy Papers

As noted by Scotten (2011), “a policy paper is a research piece focusing on a specific policy issue that provides clear recommendations for policy makers” (slide 3). The general purpose of policy papers is to share knowledge/research on a specific policy issue in an easily accessible and understandable format, in order to inform a policy maker’s decisions around said issue. Policy papers are typically written in plain language (which you will learn more about below) and are short documents which may be accompanied by plain language summaries of related research (Political Science Guide, 2017).

Deeper Dive

To take a deeper dive, below are some additional resources with further information on policy papers:

- Glover, D. (2002). What makes a good “policy paper”? Ten Examples. EEPSEA special paper/IDRC. Regional Office for Southeast and East Asia. https://idl-bnc-idrc.dspacedirect.org/bitstream/handle/10625/27168/118102.pdf

- Herman, L. (2013). Tips for writing policy papers. Stanford Law School. https://www-cdn.law.stanford.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/White-Papers-Guidelines.pdf

- Political Science Guide. (2017). Policy paper. https://politicalscienceguide.com/home/policy-paper/

- Scotten, A. (2011). Writing effective policy papers: Translating academic knowledge into policy solutions [PowerPoint slides]. University of Arizona. https://cmes.arizona.edu/sites/cmes.arizona.edu/files/Effective%20Policy%20Paper%20Writing.pdf

Academic KTE/KMb

Two general academic-oriented forms of KTE/KMb work include peer-reviewed journal publications and scholarly conference presentations. For both of these KTE/KMb strategies it is important to consider how to disseminate information more broadly in conjunction with academic KTE/KMb (e.g., a graphical abstract along with a journal publication).

Within all of the abovementioned strategies, having a dedicated facilitator role to support the knowledge-to-action process may be critical for KTE/KMb initiatives in a clinical setting (Kitson & Harvey, 2016). You will learn more about the importance of having staffing support for KTE/KMb in Section 4: Other Key Considerations.

Deeper Dive

There are numerous resources that can help to support KTE/KMb planning and the selection of strategies. We have included a non-exhaustive list of some of these resources below:

- Barwick, M.A. (2008, 2013, 2019). Knowledge translation planning template. Ontario: The Hospital for Sick Children. https://www.sickkids.ca/en/learning/continuing-professional-development/knowledge-translation-training/knowledge-translation-planning-template-form/

- Briggs, G., Briggs, A., Whitmore, E., Maki, A., Ackerley, C., Maisonneuve, A., & Yordy, C. (n.d.). Questing your way to a knowledge mobilization strategy. https://carleton.ca/communityfirst/wp-content/uploads/KMB-Questing-Your-Way-to-a-KMb-Strategy-Jun-29-2015.pdf

- Canadian Institutes of Health Research. (2012). Guide to knowledge translation planning at CIHR: Integrated and end-of-grant approaches. https://cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/documents/kt_lm_ktplan-en.pdf

- Levin, B. (2008, May). Thinking about knowledge mobilization. In an invitational symposium sponsored by the Canadian Council on Learning and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (pp. 15-18).

- Ontario Centre of Excellence for Child and Youth Mental Health. (n.d.). Knowledge mobilization toolkit. Ottawa, Ontario. http://www.kmbtoolkit.ca

- Reardon, R., Lavis, J., & Gibson, J. (2006). From research to practice: A knowledge transfer planning guide. http://www.iwh.on.ca/from-research-to-practice.

- Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council. (2019). Guidelines for effective knowledge mobilization. https://www.sshrc-crsh.gc.ca/funding-financement/policies-politiques/knowledge_mobilisation-mobilisation_des_connaissances-eng.aspx#a1

- Government of Ontario. (2021.). How to build your knowledge translation and transfer (KTT) plan. http://www.omafra.gov.on.ca/english/research/ktt/kttplan/buildkttplan.htm

- Melanie Barwick Consulting. (n.d.). Knowledge translation tools. http://melaniebarwick.com/knowledge-translation-tools/

- Lavis, J. (2003, March 13). How can research organizations more effectively transfer research knowledge to decision makers? [Presentation]. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/50c5/429ce338c7a9f2e69d080f1cfdaf96ab74b4.pdf

- Lavis, J., Robertson, D., Woodside, J., McLeod, C., & Abelson, J. (2003a). How can research organizations more effectively transfer research knowledge to decision makers? Millbank Quarterly, 81(2), 221-248. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/pmc2690219/

- Lavis, J., Ross, S., McLeod, C., & Gildner, A. (2003b). Measuring the impact of health research: Assessment and accountability in the health sector. Journal of Health Services Research Policy, 8(3), 165-70. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/John-Lavis/publication/10655602_Measuring_the_Impact_of_Health_Research/links/54a6da0e0cf256bf8bb6a772/Measuring-the-Impact-of-Health-Research.pdf

- Phipps, D. (2011). A report detailing the development of a university-based knowledge mobilization unit that enhances research outreach and engagement. Scholarly and Research Communication, 2(2). https://src-online.ca/index.php/src/article/view/31

Plain Language Communication

A key aspect of most KTE/KMb strategies is being able to communicate in accessible terminology, or what is often referred to as plain language communication. As outlined by Wicklund and Ramos (2009), “plain language is communication that an audience can understand the first time they read or hear it. It is clear and concise, and uses short sentences and simple words. It keeps to the facts and is easy to read and understand. Plain language is simple and direct but not simplistic or patronizing” (p.178).

Watch the video below on plain language communication:

Plain language communication has become increasingly important in several areas of today’s society. For example, the United States has implemented the Plain Writing Act of 2010, which “requires federal agencies to write clear Government communication that the public can understand and use” (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2021, para. 1). See more here.

In the health care field, work has demonstrated that communicating effectively/plainly may be critically important due to the varying (and sometimes limited) health literacy levels of patients/caregivers (Wicklund & Ramos, 2009). Moreover, some research has attempted to establish the “need for plain language communication as a core competency in medical education to enable providers to better meet the needs of an increasingly globalized health system” (Warde et al., 2018, p. 52). In the KTE/KMb field, plain language communication has become a cornerstone to most work, such as in research summaries/plain language summaries, which were previously outlined in this section. As noted in their work on plain language summaries, Gudi et al. (2021) state that “often, scientific papers are authored in a complex manner using technical terminology, especially jargons, which, indeed, makes it challenging, in fact, troublesome to understand for those outside of that field. On this account, to make the science more visible and accessible, various kinds of summaries such as plain language summaries, video abstracts, graphical abstracts and podcasts have come into action” (p. 1).

One activity that you can try to test your own plain language communication skills is using the online Simple Writer tool by Randall Munroe by going here. This online tool identifies if you have used a word that is not among the 10,000 most common words in the English language. While it is not a perfect tool for ensuring that you are communicating in accessible/equitable terms, it may be helpful for demonstrating the terms that you are using which may be too complex for a general audience.

Deeper Dive

To take a deeper dive into plain language communication, here are some additional resources that may help to support further learning:

- Health Literacy Consulting (n.d.). Health Literacy Consulting. https://healthliteracy.com/

- Heath, C., & Heath, D. (2007). Made to stick: Why some ideas survive and others die. Random House LLC.

- Plainlanguage.gov. (n.d.). Home. https://www.plainlanguage.gov/

- CBC Radio. (2021, April 13). Say what? More jargon in a paper means fewer scientists will read it, study finds. CBC Radio. https://www.cbc.ca/radio/asithappens/as-it-happens-tuesday-edition-1.5985611/say-what-more-jargon-in-a-paper-means-fewer-scientists-will-read-it-study-finds-1.5985613

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2010). Simply put; a guide for creating easy-to-understand materials. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/11938

- Goldstein, C. M., Murray, E. J., Beard, J., Schnoes, A. M., & Wang, M. L. (2020). Science communication in the age of misinformation. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 54(12), 985-990.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. (2021). Plain language at AHRQ. http://www.ahrq.gov/policy/electronic/plain-writing/index.html

- Wicklund, K., & Ramos, K. (2009). Plain language: Effective communication in the health care setting. Journal of Hospital Librarianship, 9(2), 177-185.

Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion (EDI)

A very important aspect of developing KTE/KMb strategies is Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion (EDI). EDI refers to the following points (Please note that the below definitions come directly from the University of British Columbia Equity and Inclusion Office’s Equity and Inclusion Glossary of Terms (n.d.) which is available here):

Equity refers to achieving parity in policy, process, and outcomes for historically and/or currently underrepresented and/or marginalized people and groups while accounting for diversity. It considers power, access, opportunities, treatment, impacts, and outcomes, in three main areas:

-

- Representational equity: the proportional participation at all levels of an institution;

- Resource equity: the distribution of resources in order to close equity gaps; and

- Equity-mindedness: the demonstration of an awareness of, and willingness to, address equity issues.

Diversity is a concept meant to convey the existence of difference. Differences in the lived experiences and perspectives of people that may include race, ethnicity, colour, ancestry, place of origin, political belief, religion, marital status, family status, physical disability, mental disability, sex, gender identity or expression, sexual orientation, age, class, and/or socio-economic situations.

Inclusion is an active, intentional, and continuous process to address inequities in power and privilege, and build a respectful and diverse community that ensures welcoming spaces and opportunities to flourish for all.

Within the development of KTE/KMb strategies, it is critically important to ensure that you have considered all aspects of EDI, such as: who do your selected images/examples/materials represent (and importantly who may not feel represented by them), have you authentically engaged relevant context experts in the selection and creation of your KTE/KMb strategies (within this you should also consider how to respectfully compensate individuals for this work and cite them within your materials), are your KTE/KMb materials accessible, how will you incorporate land acknowledgements into your work, etc.?

Please go to Chapter 2: Data for Equity? for more information about this topic.

Deeper Dive

To take a deeper dive into some resources that may help to support EDI considerations within your work on planning KTE/KMb strategies, use these:

- Accessibility for Ontarians with Disabilities Act, 2005, S.O 2005, c. 11 (2014, July 24). https://www.ontario.ca/laws/statute/05a11

- Native Governance Center. (2019). A guide to Indigenous land acknowledgment. https://nativegov.org/a-guide-to-indigenous-land-acknowledgment/

- Accessibility for Ontarians with Disabilities Act (AODA). (n.d.). Accessibility for Ontarians with Disabilities Act (AODA). https://www.aoda.ca/

- Collaborating for Equity and Justice Toolkit. (n.d.). Collaborating for equity and justice toolkit. https://myctb.org/wst/CEJ/Pages/home.aspx

- Girratana, M. (2021). Land Acknowledgement Practices: Functions, Efficacy, Controversy, and Union College. The Charles Proteus Steinmetz Symposium. https://digitalworks.union.edu/steinmetzsymposium/steinmetz_2021/oralpresentations/275

- Government of Canada. (2021). Best practices in equity, diversity and inclusion in research. https://www.sshrc-crsh.gc.ca/funding-financement/nfrf-fnfr/edi-eng.aspx

- CAUT. (n.d.). Guide to acknowledging First Peoples & traditional territory. https://www.caut.ca/content/guide-acknowledging-first-peoples-traditional-territory

- Rudder, K. (2019, January 29). Hayden King and others question the effectiveness of land acknowledgements. The Eyeopener. https://theeyeopener.com/2019/01/hayden-king-and-others-question-the-effectiveness-of-land-acknowledgemenets/

- Web Accessibility Initiative (n.d.). Home. https://www.w3.org/WAI/

- Native Land Digital. (n.d.). Territory acknowledgement. https://native-land.ca/resources/territory-acknowledgement/

- Thomson, G. (2019, August 26). AODA requirements for educational institutions. Accessibility for Ontarians with Disabilities Act (AODA). https://www.aoda.ca/aoda-requirements-for-educational-institutions/

- U.S. Department of Arts and Culture. (2017, October 3). #HonorNativeLand [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ETOhNzBsiKA

Summary

KTE/KMb strategies are where all of your work comes together in the form of materials or initiatives that aim to spread your knowledge out to broader groups as well as engage with those groups. As outlined in this section, there are numerous KTE/KMb strategies that can be implemented, but these strategies are not one-size fits all approaches and need to be selected based on several factors (e.g., type of research, feedback from context experts, EDI considerations, budget, etc.). Additionally, individuals/groups should try to base their KTE/KMb strategies off of some form of equitable knowledge exchange with relevant groups/experts. Finally, this section touched on the importance of plain language communication when developing KTE/KMb strategies.

Test Your Knowledge

Complete the following activity to assess how much you learned about the content that was covered in this section.

The many activities that contribute to the relational, iterative, and context-sensitive process of moving of knowledge to action, including the synthesis, dissemination, exchange, and application of knowledge.

The interrelated conditions in which something exists or occurs (Merriam-Webster, 2022).

Individuals with lived experience of the situation or issue at hand (Attygalle, 2017).

The potential audience of created knowledge.

Individuals with formal power who have knowledge, tools, and resources to address the issue (Attygalle, 2017, p. 3).

A synopsis of research findings written in an easily understandable way, so that even a lay audience would grasp the content (Gudi et al., 2021, p. 1).

Visual/graphical depiction of information.

The knowledge and skills required to create meaningful tables, charts and graphics to visually present data (Statistics Canada, 2020). This also includes evaluating the effectiveness of the visual representation (i.e., using the right chart) while ensuring accuracy to avoid misrepresentation.

A single, concise, pictorial, and visual summary of the main findings of an article (Elsevier, n.d.).

A process that uses diverse art genres (e.g., visual arts, performing arts, creative writing, multimedia including video and photography) to communicate research with the goal of catalyzing dialogue, awareness, engagement, and advocacy to provide a foundation for social change on important societal issues (Kukkonen and Cooper, 2019, p. 293).

A research piece focusing on a specific policy issue that provides clear recommendations for policy makers (Scotten, 2011).

Communication that an audience can understand the first time they read or hear it (Wicklund & Ramos, 2009, p.178). It is clear and concise, and uses short sentences and simple words. It keeps to the facts and is easy to read and understand. Plain language is simple and direct but not simplistic or patronizing plain language communication.

Achieving parity in policy, process, and outcomes for historically and/or currently underrepresented and/or marginalized people and groups while accounting for diversity (The University of British Columbia, n.d.).

A concept meant to convey the existence of difference (The University of British Columbia, n.d.).

The proportional participation at all levels of an institution (The University of British Columbia, n.d.).

The distribution of resources in order to close equity gaps (The University of British Columbia, n.d.).

The demonstration of an awareness of, and willingness to, address equity issues (The University of British Columbia, n.d.).

An active, intentional, and continuous process to address inequities in power and privilege, and build a respectful and diverse community that ensures welcoming spaces and opportunities to flourish for all (The University of British Columbia, n.d.).

A collaboration involving regular sharing of information, ideas, and experience between those who generate knowledge and those who might put the knowledge to use (Reardon et al., 2006).