Section 3: Factors Influencing Change Efforts

Dr. Madelyn P. Law; Dr. Elaina Orlando; and Lidia Mateus

Section Overview

This section will highlight several core concepts at the micro, meso, and macro-level that influence change efforts. Moving from the previous section focused on frameworks supporting implementation, this section helps to understand the dynamics between individuals and their organizational environment and how that influences the ability to use data to foster change in the health sector.

Section Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Define and understand micro, meso, and macro-level factors that influence change;

- Critically reflect on examples of micro, meso, and macro-level factors in relation to the concepts; and

- Synthesize the information across these levels to explain why change succeeds or fails.

Test Your Knowledge

Complete the following activity to assess how much you already know about the content that will be covered in this section.

Introduction

Without question, there are numerous change management models and theories available. The video below is from Kotter’s 8 Step Change Management Model. We present this model here to start out the section as a broad framework of steps that gives consideration to micro, meso, and macro levels. Kotter’s model is one of the most widely used, likely because it is easy to understand, makes intuitive sense, and has demonstrated great utility in organizations.

In terms of thinking about this model in relation to supporting individuals’ and organizations’ use of data to drive their decisions, this can be seen in many of the steps. For example, using data to create a sense of urgency for the change is essential. Highlighting what is wrong with the current system, using data and evidence, will help individuals identify what needs to be modified and feel confident about the impeding change. Having a clear vision for a change that has an evidence-informed goal with measurable outcomes will allow for a clear vision of change. Using data to demonstrate short-term wins will help to reinforce behaviours and the desired change. The use of data in this approach is twofold: you may want to see new evidence-informed practices become integrated within an organization and Kotter’s model provides change management steps to achieve this. We can use data throughout the process of change to help individuals buy-in to the change and succeed in making this part of the way they work in the future.

Micro-Level Change

Micro-level factors are those that are at the individual level. Change at an individual level equates and rolls up to a larger meso level change seen in an organization. Organizations use numerous tactics to influence, persuade, and accept change, but to do so, it is important to understand what types of factors may impede or support the individual behaviours that one is trying to achieve. This is particularly important to consider when thinking about how we get individuals to use data to drive decision-making. What are those individual factors that play a role in why an individual may choose to use data?

Educational Background

Using data in decision-making is not an inherent skill nor is it something that is taught explicitly in all educational programs. As educators and academics, we do ask students to use research and evidence in authoring their papers and other types of assignments. However, if students have not had the chance to engage in cases or experiential opportunities that allow for critically reviewing and using data to analyze a problem and provide recommendations and future steps, then this skill has not been realized before entering a profession. In the health field, this skill is vitally important. Having an educational program that promotes the use of data and is also explicit in identifying and discussing the topics (such as those in this book!) will in turn support individual skills, knowledge, and attitudes towards the importance of using data to drive decisions.

Psychological Safety

You may be wondering how psychological safety relates to the frameworks, tools, and measurements of implementation science. At the individual level, psychological safety is extremely important in creating a working environment that fosters the development and adoption of innovation, which are key to the central purpose of implementation science (Edmondson et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2018). A variety of factors impact psychological safety within and across organizations including leadership styles, organizational culture, social support, recognition, and psychological demands on employees, among others. While it is outside the scope of this chapter to discuss each of these many factors, the section that follows will give you an understanding of how to develop psychological safety within a team and how this impacts performance.

Psychological safety can be defined as being able to communicate concerns, express questions, provide ideas, or admit mistakes without fear of negative consequences such as punishment, humiliation, or damage to career or status (Javed et al., 2017). It is recognized as being critical to helping people learn new behaviours and enact change in complex and high-stakes contexts (e.g., modifying workflow processes, implementation of best practices, adopting change in emergency departments, etc.). Creating a psychologically safe work environment begins with those in leadership positions. One strategy is to create opportunities for dialogue and reduce barriers that exist by providing formal and informal opportunities for feedback, allowing staff to provide anonymous feedback, and having open meetings for employees across organizational levels (Grailey et al., 2021). Another is for leaders to model openness and fallibility to their team members by being transparent about errors and near-misses. Leaders can also develop policies and share human resources information that promotes civility and accountability among employees. Even actions as simple as using supportive language, learning the names of team members, and recognizing accomplishments during meetings can improve psychological safety within an organization.

Organizations with elevated levels of psychological safety are positively correlated with knowledge sharing, creative performance, technical performance – extending to patient outcomes in health care settings, and continuous quality improvement efforts among employees (Javed et al.2017; Grailey et al, 2021). Leaders can shape employees’ perceptions of the organizational culture and context in a way that directly impacts their psychological safety. When leaders use their influence to create an open, inclusive, and communicative environment, they directly facilitate employee innovative work behaviour and learning. Creating psychologically safe environments is key to encouraging employees to partake in implementation science and related improvement activities.

Grief Cycle and Individual Response to Change

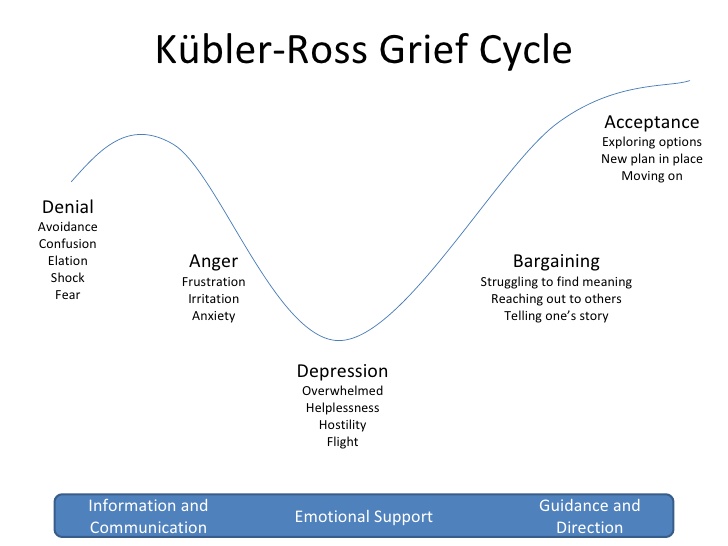

The Kubler-Ross Grief Cycle has been used to help understand resistance to change and the stages that individuals must go through before there is acceptance of a new change. When asked to change, there is an associated loss to an individual and they must, therefore, grieve that loss. Individuals will go through the stages of grief at different rates. Some will move quickly, others may take some time to process and move forward, while some might never be able to let go of the existing practice that is being changed. In the Kubler-Ross Grief Cycle, there are five stages that an individual progresses through, which are outlined in Figure 3.4:

Meso Level

Meso-level factors are those that are at an institutional level. For example, thinking about an organization-wide change to a new electronic medical record system given that the evidence demonstrates that the new system will enhance efficiencies and reduce medical errors. All individuals in an organization will collectively have to move to a new system, but there are numerous organizational-level factors that will impact the success of this type of change, including readiness, organizational culture, teamwork, leadership, and diffusion of innovation.

Organizational Readiness for Change

Above we discussed the concept of individual readiness, which in turn, dictates the organizational readiness for change. Weiner (2009) defines organizational readiness for change as “a shared psychological state in which organizational members feel committed to implementing an organizational change and confident in their collective abilities to do so.” (p. 6). In this definition, there are two key factors that are of importance: “committed” and “confident”. As outlined by Weiner (2009), to be confident in moving forward with the change, individuals must feel like the organization has the supports in place for them to be successful. More recently, Shea et al. (2014) describe organizational readiness as “‘the extent to which organizational members are psychologically and behaviourally prepared to implement organizational change”. Implementing organizational changes is a complex and multi-layered process and any large-scale change requires “collective action by many people, each of whom contributes something to the implementation effort” (Weiner, 2009, p. 2). When people feel committed and confident in a change, their readiness to change is high and they are more likely to engage in change efforts.

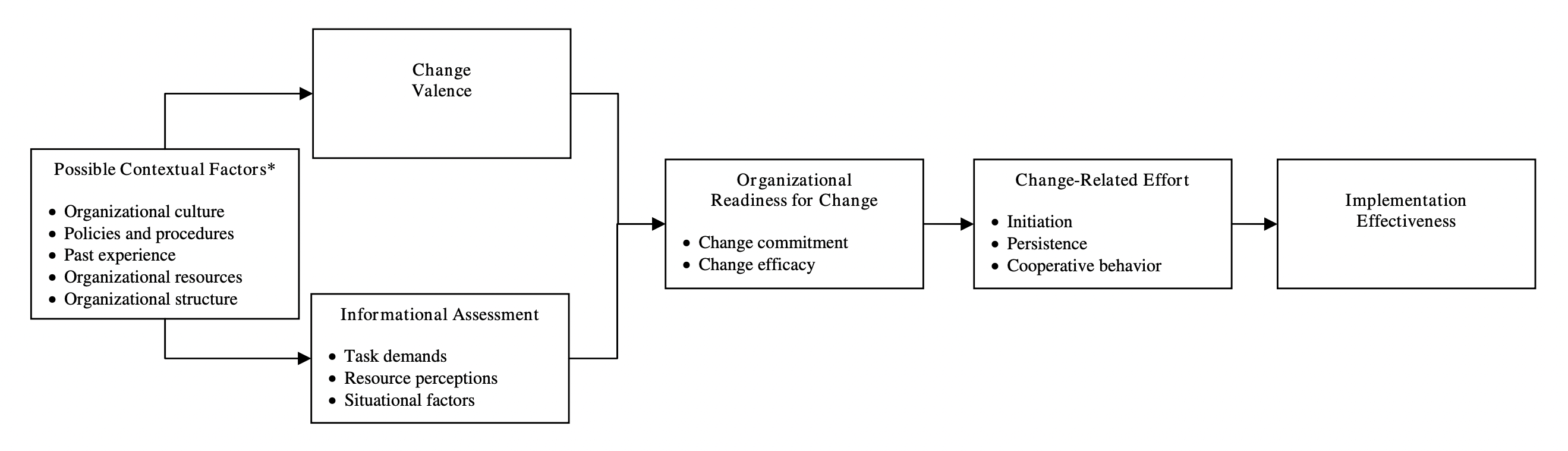

Figure 3.5 provides an overview of the theory of organizational readiness for change. The figure outlines possible contextual factors, including organizational culture, policies and procedures, past experience, organizational resources, and organizational structure, and how these flow to the concept of change valence (i.e., how much individuals value the change) and informational assessments (i.e., task demands, resource perceptions, and situational factors). Together, these aspects form the change commitment and change efficacy, which corresponds to organizational readiness for change. This leads to change-related effort, including initiation, persistence, and cooperative behaviour, which ultimately leads to implementation effectiveness.

Thinking through this concept in relation to using data to drive change is interesting and multi-faceted. An organization that values and uses data to drive decisions would want to make sure they leverage the data messaging through core communications for a pending organizational change. Using statistics and new research to communicate the urgency of change to organizational members would in turn help to develop change valence and encourage commitment and confidence in the change.

One example of this is the COVID-19 pandemic response in public health units in terms of holding pop-up vaccine clinics. Fears circulated about no one showing up and clinics not being in the right place that was accessible to all. The change in the model of delivery from static clinics to drop-in pop-ups was a major operational shift requiring workflow changes and major organizational reconfigurations. Public health units were able to leverage existing vaccine rate data, together with numerous social determinants of health and mobility data, to make the case for specific locations which would help to support location decisions. This resulted in being able to gather commitment from staff and confidence in the fact that the effort to shift to this mode of delivery was the right one to serve those populations most at risk with low vaccine rates.

Organizational Supports

Aligned with this notion of an organizational culture that values the use of data in driving decisions, it is also essential that there are organizational supports and resources that will enable this to be realized in practice. Having a division that is dedicated to proactively reviewing data and providing this information in real-time to those decision-makers helps to encourage and support the use of data in decision-making. This must also be backed up with the proper training and methods (e.g., dashboards, reporting schedules, relationships) that would enable the use of data. For example, in a public health unit, a dedicated team of epidemiologists, program evaluation specialists, and quality improvement facilitators who are part of a program delivery team would have the role of creating excellent data collection tools, reporting, and knowledge mobilization methods that would support the entire project team in the success of their work. An organization that invests in supports for evidence-based decision-making will in turn, support a culture of evidence-informed decision-making.

Teamwork

A team is a group of individuals with interdependent tasks and a shared responsibility of outcomes (Cohen & Bailey, 1997). A strong team shares a common goal, possesses its own set of norms, and can be open and trusting with each other. Strong teams are vital in health care as they can positively impact patient outcomes (Baggs et al., 1999), lead to higher quality and safer care, and improve work satisfaction for staff (Rosenstein & O’Daniel, 2008). There are four key team processes: communication and collaboration, leadership, decision-making, and conflict. It is important to recognize that the context in which a team works can have direct impacts on its performance, cohesion, and effectiveness. This can contribute positively or negatively toward effective team dynamics. When there is a positive dynamic and cohesive team, this can be an immense competitive advantage for an organization (Lencioni, 2002).

There are five stages of team development as identified and researched in 1965 by Bruce Tuckman, which continue to hold true today. The five stages of team development remains one of the most used frameworks for understanding how teams function. Stage 1 is called “Forming”. This stage is characterized by relationships being established among team members, wherein communication is guarded, and individuals are on their best behaviour. In Stage 2, “Storming”, the team has developed a level of comfort with each other that enables the free expression of one’s personal views and agendas. This can generate stress among the team and conflict may arise. Stage 3, “Norming”, sees the team transition to a more cooperative form of working together. The energy of individuals tends to be focused on team goals and productivity as well as effectively resolving conflicts. By Stage 4, the team begins “Performing” and starts to see the output of a strong team. There is a high level of cooperation, shared leadership, and facilitation among the group and a collective celebration of progress. The final stage in the model, Stage 5, is “Adjourning” or the cease-function(ing) of the team. The end of the team may be a result of changing organizational structures or when a project has been completed. This stage is characterized by team members experiencing different feelings including anxiety, sadness, and satisfaction.

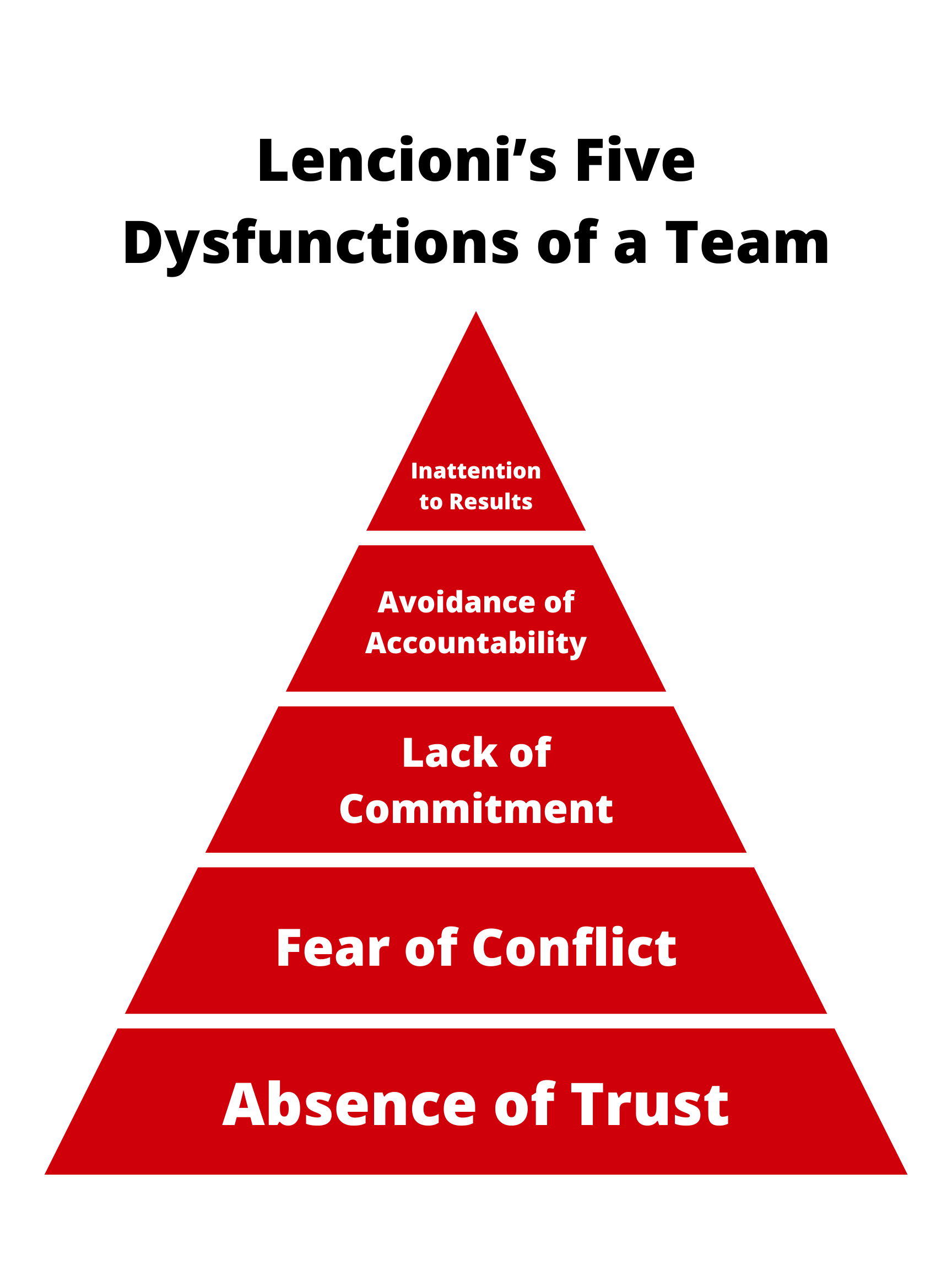

In 2002, Patrick Lencioni published the model, “Five Dysfunctions of a Team” to assist organizations and leaders with understanding where they can intervene to create more highly effective teams (Lencioni, 2002). The model is intentionally structured in a pyramidal way to show that elements of team functioning, much like the team themselves, are interdependent and need to be built step-by-step on a strong base.

In his model, the foundational dysfunction of the team is an absence of trust (Lencioni, 2002). Lencioni (2002) describes the concept of vulnerability as having a definitive role in the absence or presence of trust among team members. Where trust does not exist or has difficulty flourishing, we often find team members who fear being vulnerable. Lencioni (2002) suggests that it is the leader of the team who must go first to demonstrate vulnerability and show the rest of the team members that it is acceptable to do this. According to this model, when team members demonstrate vulnerability, they can help foster trust among each other and overcome the team dysfunction of absence of trust.

The second step in the pyramid of dysfunction is the fear of conflict (Lencioni, 2002). This reflects the “Forming” stage of team development wherein members attempt to preserve the artificial harmony among the group and suppress productive conflict. According to Lencioni (2002), this is a result of the absence of trust. The ability to successfully deal with conflict is key to the progress of teams through their development. In fact, conflict can be quite beneficial to a team if they have established ways of dealing with it and have a solid foundation of trust to manage through difficult times.

Third in Lencioni’s model is lack of commitment (Lencioni, 2002). Lencioni (2002) indicates that without healthy and productive conflict among the team, there is lack of clarity regarding the plans, actions, and focus of the team. When the goals are unclear to team members, they are reluctant to consistently take action to benefit the team and are reluctant to make decisions.

The inability to commit to a clear team direction and take actions can generate an avoidance of accountability among the team (Lencioni, 2002). There can be reluctance to hold each other accountable or ask for help to perform tasks because the goal is unclear and there is a fear of conflict.

The final dysfunction is inattention to results stemming from the pursuit of individual goals above the team’s collective success (Lencioni, 2002). The act of putting personal needs, successes, and development above the team goals is a result of failing to hold one another accountable for actions and performance.

Organizational Culture

Edgar Schein (2010) is one of the most notable scholars in organizational culture, which is defined as: “a pattern of shared basic assumptions learned by a group as it solved its problems of external adaptation and internal integration, which has worked well enough to be considered valid and therefore, to be taught to new members as the correct way to perceive, think and feel in relation to those problems.” (p.18)

There are three fundamental levels of organizational culture: observable artifacts, values, and basic underlying assumptions. At level one, artifacts are the visible, tangible, and/or audible results of behaviour, such as the physical layout of the organization, statements, meetings, and personal protective equipment (Guldenmund, 2000). These artifacts could be statements in strategic plans that use words like “evidence informed decision” or “use of data to drive innovation”. Values are the next level of the organizational culture, which refers to the reason why certain observed phenomena happen the way they do. Values are the conscious, affective desires and wants (Schein, 1990; Ott, 1989). Examples of an individual who has a value focus on data would be the school public health nurse calling the epidemiologist to ask for the latest data on her school’s vaccine rates and for any current research on interventions on how to enhance vaccine uptake in a targeted age group. Behaving in a way that aligns with the stated value demonstrates an alignment of the culture. The third level of organizational culture is the basic underlying assumptions, defined as perceptions, thought processes, feelings, and behaviours (Schein, 1990). Basic assumptions are unconscious, relatively unspecific, and permeate the whole organization. An example would be observing a Vice President of a hospital discussing data trends for inpatient fall rates and working with directors to determine how they can use this data to drive improvements in their unit. If you asked this Vice President, “what prompted that discussion?”, they would most likely say, “because that is just the way we do things around here.” This denotes the fact that they do not consciously think about the reason they use data to drive their decision – it has just become an ingrained behaviour.

Having a culture that values the use of data in their decision-making is, arguably, the most important factor in driving change and improvement in health care. If individuals do not value the use of data to inform their behaviours, or the organization does not explicitly state and reinforce the use of data, then why would individuals use evidence to inform their decisions?

Leadership

Over centuries, leadership thought has developed from studying military and political leaders who have inspired others to follow them toward a deeper understanding of the contextual influences on leadership. In the 1940s and 1950s, leadership research was focused on the identification of traits that seemed to be characteristic of successful leaders. This transitioned to a behavioural approach to leadership research that examined the impact of leadership styles on work-group performance and satisfaction. Because of the lack of success of trait and behavioural models in predicting leadership success, contingency models evolved that proposed that the type of leadership needed should depend on the situation or circumstances. In the early 80s, charismatic leadership, which focuses on inspiring others, was discussed as the complex evolving from the relationship between the leader, the followers, the context, and the ideas. Transformational leadership became the model for leadership behaviour for almost all organizations in the last quarter of the 20th century as they sought to transform organizations in contrast to maintaining the status quo as is found with transactional leadership.

Distributed Leadership

Although distributed leadership is not a new concept insofar that it was first described by Gibb in 1954, it has become increasingly important as it pertains to facilitating organizational change. Gibb (1954) describes distributed leadership as leadership that is collective in nature and extends beyond a singular individual within an organization. The importance of this style of leadership, which is not solely top-down in nature, has been reinforced in a number of studies where the notion of collective, distributed, or concentric leadership is seen as important to facilitating successful organizational change within health care (Battilana et al., 2010; Buchanan et al., 2007; de Búrca, 2008; Denis, et al. 2001; Lukas et al., 2007; Roberts & Coghlan, 2011).

Individuals in formal leadership roles can encourage distributed leadership through appropriate structures (Roberts & Coghlan, 2011) and processes (Buchanan et al., 2007), while being cognizant that organizational cultures can act as a barrier to distributed leadership (Roberts & Coghlan, 2011). It has been suggested that for distributed leadership to be successful, approaches to support distributed leadership must be aligned with the goals of the senior organizational leadership (Battilana et al., 2010). The effectiveness of distributed leadership may also be impacted by the composition of the leadership team (Denis et al., 1996).

This changing view of leadership away from individualistic models and the heightened focus on distributed leadership has the potential to greatly impact how we approach and implement change within health care. There are multiple existing structural and professional hierarchies that exist in most health care organizations, and the ability to generate distributed leadership, wherein individuals throughout the organization play leading roles in driving successful change, may be imperative to achieving the desired outcomes. Distributed leadership doesn’t spontaneously arise, however, as it requires strong, formalized, leadership to actively encourage its existence for it to develop.

The Diffusion of Innovation Theory

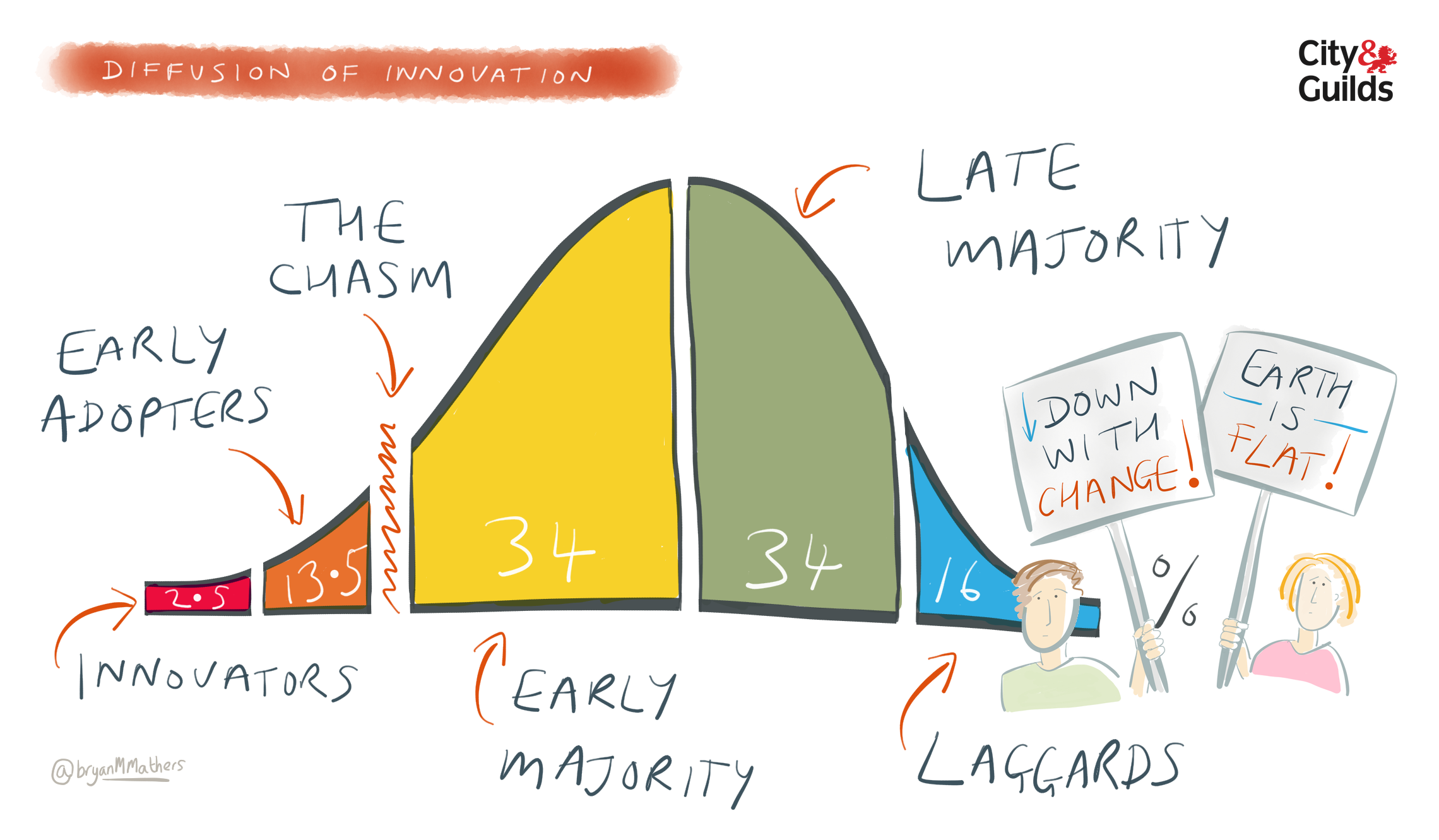

The Diffusion of Innovation Theory was developed in 1962 by Everett M. Rogers in the field of communications. This theory describes the pattern by which groups of people are likely to adopt an innovation over time (Robertson, 1967). In this theory, the population is divided into five groups: innovators, early adopters, early majority, late majority, and laggards. Innovators, who comprise 2.5% of the population, are the first to adopt the change. This is followed by the early adopters, who comprise 13.5% of the population, the early majority, who comprise 34% of the population, the late majority, who also comprise 34% of the population, and finally, the laggards, who comprise 16% of the population (Bhattacharya & Singh, 2019). As the innovation curve progresses from left to right, the people who fall into each category are slower to adopt change, ending with the laggards who are either very late to adopt or simply resist change altogether.

There are five key factors that can be used to leverage the adoption of a change. First is competitive advantage: people must perceive the change as being better than the previous course of action. Second is compatibility: the change must be compatible with the needs, values, and/or culture of the target population. Complexity also plays a role and innovation should be user-friendly and easy to understand. Next, there is testability: the ability of the target population to test innovation before committing to the change. The final factor to leverage is observability: the ability of the innovation to result in measurable change. The Diffusion of Innovation Theory is a useful framework that allows us to understand how innovation may be adopted within organizations. It also provides us with methods for effective ways to introduce and implement innovation that may enhance the likelihood of successful uptake.

The video below provides a quick overview of the Diffusion of Innovation Theory:

Deeper Dive

- Read this article about a road map for diffusion of innovation in health care: https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/10.1377/hlthaff.2017.1155?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%20%200pubmed

Macro Level

Macro-level factors are defined by Smith et al., (2019) as those that are “structural, legal, regulatory or economic conditions that are often beyond the influence of a specific individual or an organization itself”. These macro-level factors include government regulations, accreditation standards, state of the workforce at any given time, and any associated health policies. All these factors will have an influence on the change activities that must occur in an organization. Of interest here is how these macro-level factors, by design, require organizations to collect, report, and act upon data to enhance health services. Ultimately, some organizations would be doing this regardless, given their culture of evidence-informed decision-making. However, these macro-level factors do make this somewhat of a requirement that helps to motivate some who may otherwise not help to reinforce specific changes and actions for those organizations.

Governmental Regulations

Regulations, legal acts, and associated policies that are passed or enacted at a provincial level or national level, as is the case in Ontario will, in turn, impact an organization’s requirement for change. Often, organizations will be tasked with understanding these requirements within their own context and then creating their own strategies and changes to align with them. An example of an Act that supported changes to enhance health system quality was the Excellent Care for All Act. This Act required that all organizations establish quality committees, create, and implement quality improvement plans, link executive compensation to achievement of quality targets, ensure that staff and patient satisfaction surveys were done, develop a declaration of values through public consultation, and establish a patient relations process. Hospitals, and subsequently other health organizations, such as long-term care and community health centres, were required to enact these activities. How this was done varied but all had requirements for reporting to the government. What many of these activities then required was the collection of data, reporting, and then acting on areas that required improvements. In a way, these activities helped to drive the culture of using evidence to inform decision-making to enhance quality in organizations.

Accreditation Standards

Accreditation is defined as “the action or process of officially recognizing someone as having a particular status or being qualified to perform a particular activity” (Lexico, n.d.). Logically, we would want to make sure that our health care organizations are accredited. Depending on the health sector, there are accreditation bodies that are either mandatory or voluntary. For example, hospitals must go through an accreditation process every five years, whereas public health units may elect to move through an accreditation cycle, but this is not currently mandated by the provincial government bodies. Accreditation in the health sector is focused on ensuring that high-quality services and programs are delivered to our communities. For example, Accreditation Canada (n.d.) “inspires people to make positive change that improves the quality of health and social services in Canada and around the world.” Through this accreditation process, organizations work through achieving a set of standards and modifying their practices to ensure they meet these standards. The standards are informed by the best available evidence and the current health system context that are created in collaboration with providers, patients, and policy makers. This ongoing process helps organizations identify areas of weakness and make necessary changes. Surveyors attend the site to review the changes, ask questions, and engage in discussions about areas for improvements that they see as outsiders of the organization. The process supports high-quality services and continuous improvement based on evidence in reports, observations, and qualitative information during onsite visits.

Summary

As the title of this chapter suggests, implementing change is easier said than done. Factors at the micro, meso, and macro-level influence the success of a change. New knowledge on processes and practices that is gleaned through research is not enough to influence behaviour or process change to a new state. Understanding factors that impact how individuals use new information and what motivates individuals to incorporate new evidence into their decision-making is an essential part of fostering change in our health system.

Test Your Knowledge

Complete the following activity to assess how much you learned about the content that was covered in this section.

Deeper Dive

Check out these resources for more information on the topics that were covered in this section:

Factors that are at the individual level.

Factors that are at an institutional level.

Factors that are structural, legal, regulatory or economic conditions that are often beyond the influence of a specific individual or an organization itself (Smith et al., 2019).

The process, tools, and techniques used to manage change, including planning, validating and implementing change, and verifying effectiveness of change (American Society for Quality, 2022a).

The practice and process of supporting people through change, with the goal of ensuring that the change is successful in the long-term (World Health Organization, 2019, p. 3). Change management helps people to change their behaviors, attitudes, and/or work processes to achieve a desired business objective or outcome.

Being able to communicate concerns, express questions, provide ideas, or admit mistakes without fear of negative consequences such as punishment, humiliation, or damage to career or status (Javed et al., 2017).

The scientific study of methods to promote the systematic uptake of research findings and other evidence-based practices into routine practice, and, hence, to improve the quality and effectiveness of health services and care (Eccles & Mittman, 2006).

A pattern of shared basic assumptions learned by a group as it solved its problems of external adaptation and internal integration, which has worked well enough to be considered valid and therefore, to be taught to new members as the correct way to perceive, think and feel in relation to those problems (Schein, 2010).

The interrelated conditions in which something exists or occurs (Merriam-Webster, 2022).

A shared psychological state in which organizational members feel committed to implementing an organizational change and confident in their collective abilities to do so (Weiner, 2009).

The many activities that contribute to the relational, iterative, and context-sensitive process of moving of knowledge to action, including the synthesis, dissemination, exchange, and application of knowledge.

The knowledge and skills required to use data to help in the decision-making and policy-making process (Statistics Canada, 2020). This includes thinking critically when working with data, formulating appropriate business questions, identifying appropriate datasets, deciding on measurement priorities, prioritizing information garnered from data, converting data into actionable information, and weighing the merit and impact of possible solutions and decisions.

A group of individuals with interdependent tasks and a shared responsibility of outcomes (Cohen & Bailey, 1997).

Leadership that is collective in nature and extends beyond a singular individual within an organization (Gibb, 1954).

The action or process of officially recognizing someone as having a particular status or being qualified to perform a particular activity (Lexico, n.d.).