Section 2: Introduction to Theories and Models of Knowledge Translation/Mobilization

Dr. Karen A. Patte; Jayne Morrish; and Megan Magier

Section Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Understand key KTE/KMb theories, frameworks, and models; and

- Explain elements common across many theories, models, and frameworks and how they can be applied to KTE/KMb planning.

Test Your Knowledge

Complete the following activity to assess how much you already know about the content that will be covered in this section.

Background

KTE/KMb theories, models, and frameworks can assist in designing and implementing more effective plans. Theories convey how change and KTE/KMb occurs, models guide the process, and frameworks explain the factors believed to influence an outcome. However, the proliferation of KTE/KMb literature has created confusion around which to select (Esmail et al., 2020; Strifler et al., 2018). A 2018 scoping review identified 159 unique KTE/KMb theories, models, or frameworks, and the majority (87%) were used in five or fewer studies, with 60% used only once (Strifler et al., 2018). Models were most commonly used to inform KTE/KMb planning/design, implementation, and evaluation activities, and least commonly to inform dissemination and sustainability/scalability activities. Given the countless theories, models, and frameworks, this chapter will cover the most frequently cited examples to guide KTE/KMb design and understand the mechanisms and components involved in the process of moving knowledge to action.

KTE/KMb Theories, Models, and Frameworks

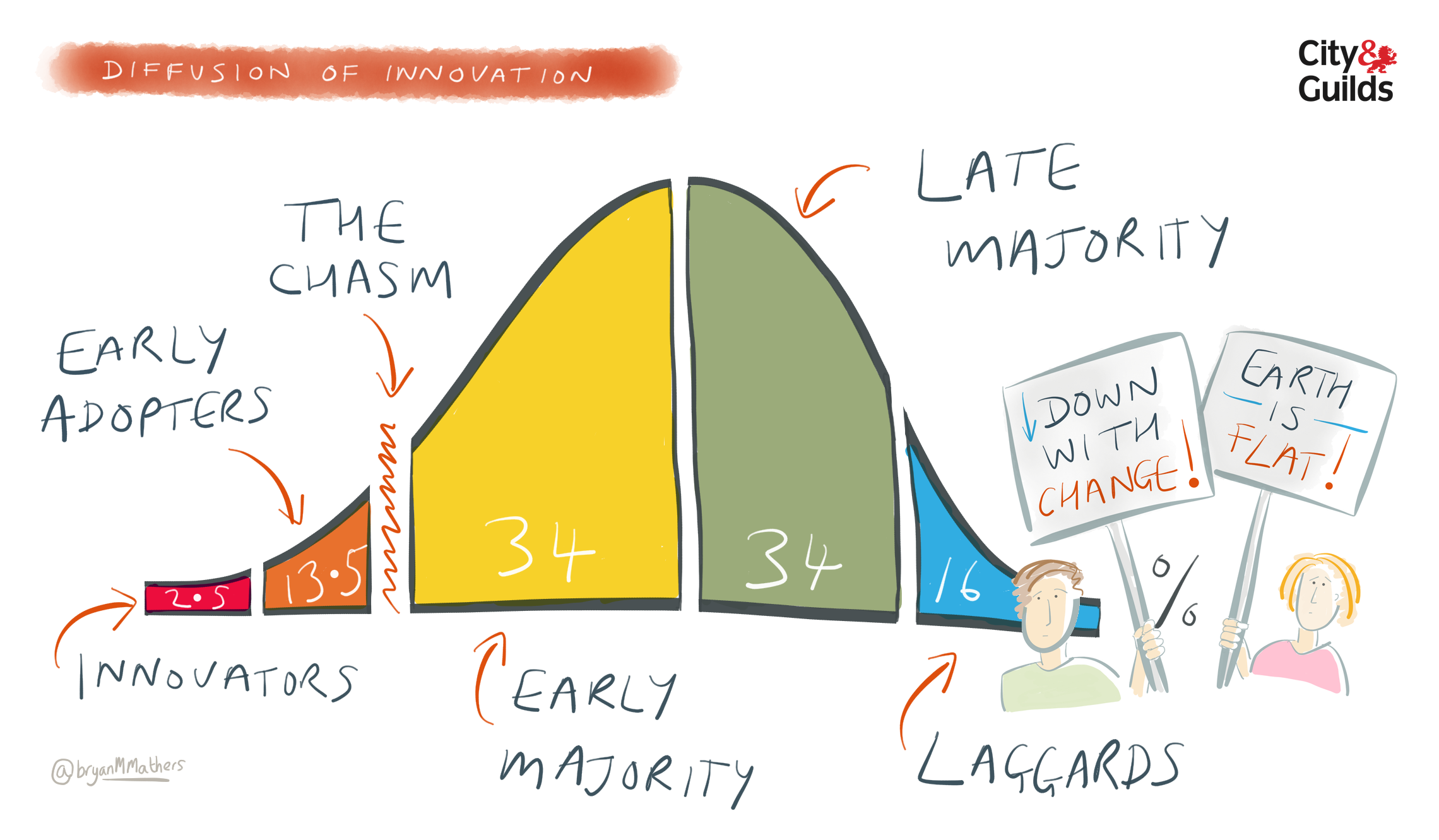

Diffusion of Innovation Theory (Everett Rogers, 1962)

Everett Rogers (1962) was a Professor in Communication Studies who theorized how new ideas or behaviours gain momentum and spread through a social system over time. As outlined in Chapter 3: Implementing Change – Easier Said Than Done, Rogers established the Diffusion of Innovation Theory, which outlines five segments of the population that adopt new ideas or behaviours at different times:

Rogers (1962) proposed that adoption occurs in five stages:

- Awareness: An individual becomes aware of the idea, behaviour, or product;

- Persuasion: An individual develops a favourable or unfavourable attitude toward the idea, behaviour, or product, and are compelled to seek out information;

- Decision: An individual decides to adopt or reject it, weighing the pros and cons;

- Implementation: An individual tries it but is still deciding whether to continue; and

- Continuation: An individual evaluates the results and comes to a final decision about whether to continue with the idea, behaviour, or product.

The Diffusion of Innovation Theory was not developed explicitly to apply to new health behaviours or innovations, although it has been applied in multiple fields, including public health. Several limitations of the theory have been noted, including that it does not foster a collaborative partnership or participatory approach to adoption of health programs, it works better with the adoption of new behaviours rather than the cessation or prevention, and it does not account for individual’s resources or social support for adoption.

Deeper Dive

To take a deeper dive, try this resource:

- Green, L. W., Ottoson, J. M., García, C., & Hiatt, R. A. (2009). Diffusion theory and knowledge dissemination, utilization, and integration in public health. Annual Review of Public Health, 30, 151–174. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.031308.100049

Lavis et al. (2003b) “Push, Pull, Exchange, Integrated KT” Model

Developed for health care decision-making, but widely applicable, Lavis and colleagues (2003b) described four general categories of KTE/KMb strategies:

Lavis and colleagues (2003a) have also presented a KTE/KMb framework that highlights 5 questions for research teams to consider when working to mobilize knowledge:

- What should be transferred to decision makers (the message)?

- To whom should research knowledge be transferred (the target audience)?

- By whom should research knowledge be transferred (the messenger)?

- How should research knowledge be transferred (the knowledge-transfer processes and supporting communications infrastructure)?

- With what effect should research knowledge be transferred (evaluation)?

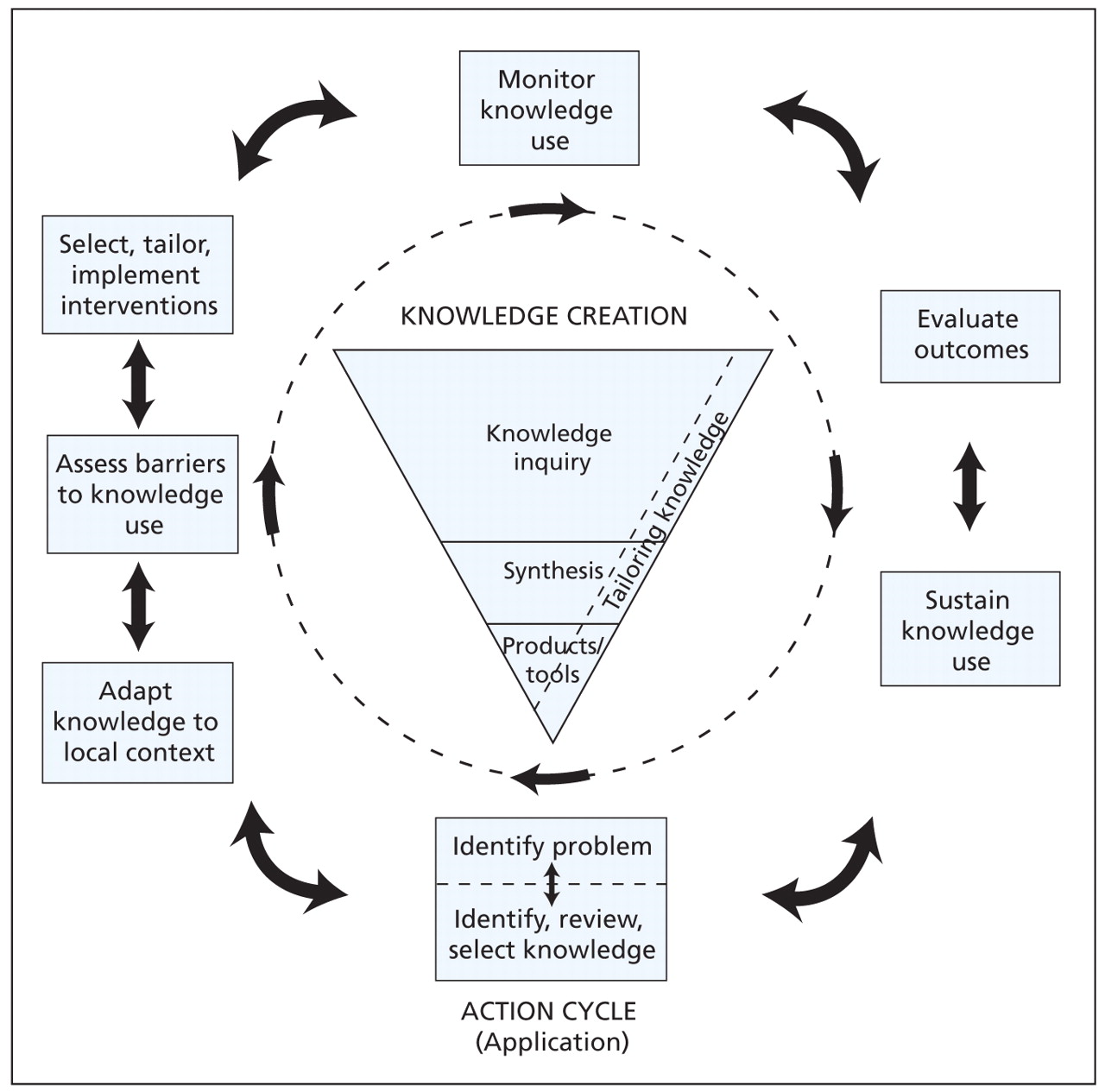

Knowledge-to-Action (KTA) Cycle (Graham et al., 2006)

One of the most highly cited frameworks for guiding KTE/KMb is the Knowledge-to-Action (KTA) cycle. The framework was originally developed by Dr. Graham and colleagues in 2006, and later adapted by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) and other organizations globally.

The KTA cycle consists of two larger components:

The KTA cycle takes a systems perspective, which Graham et al. (2006) describe as “situating knowledge procedures and users in a system of knowledge that is responsive, adaptive, and unpredictable”. Phases are connected by bidirectional arrows to emphasize that the KTA process is iterative and dynamic; one can start at any phase, and the steps do not necessarily occur in sequence. The action cycle components can also inform knowledge creation.

permission from Straus et al. (2009)

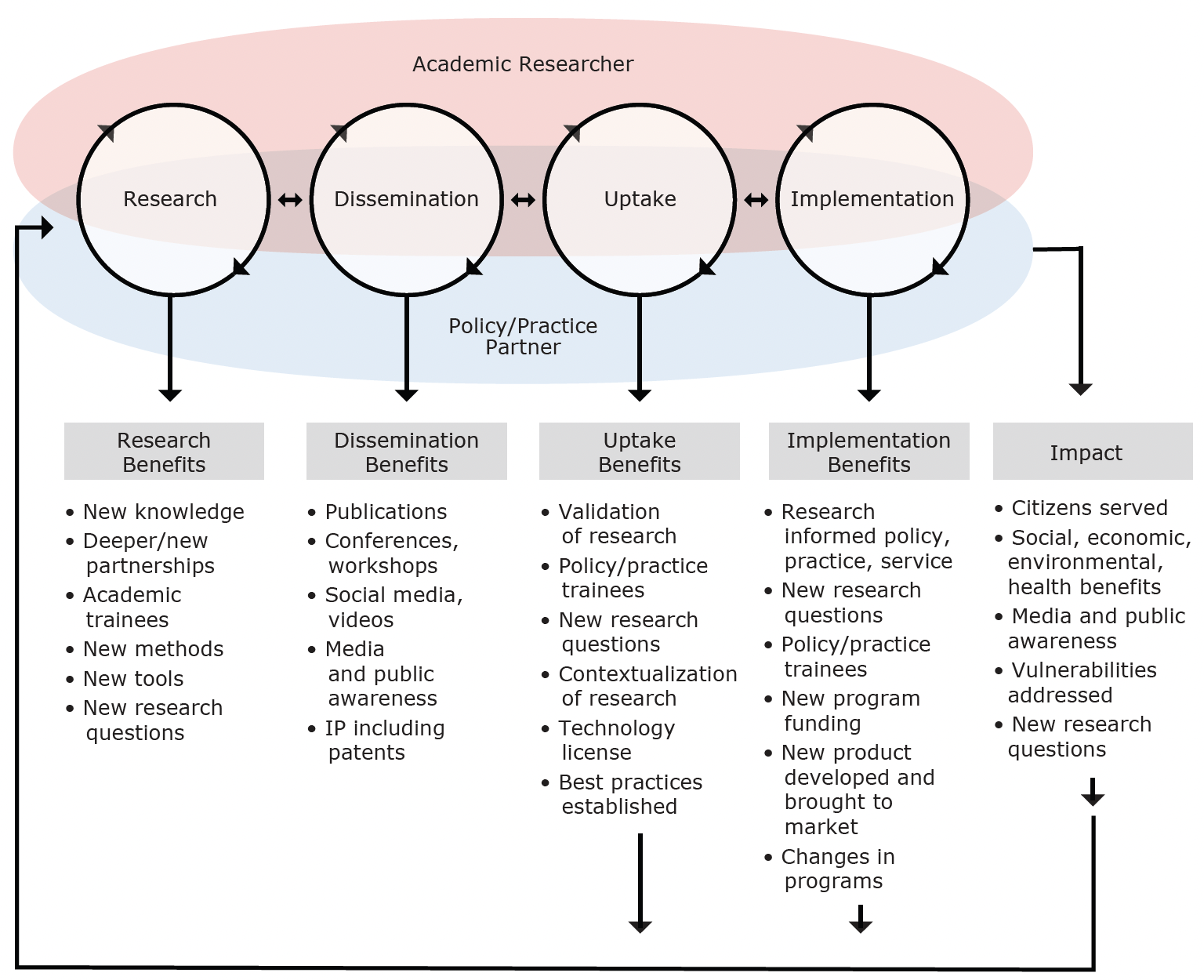

Co-Produced Pathway to Impact (Phipps et al., 2016)

More recently, the Co-Produced Pathway to Impact was developed by Phipps and colleagues (2016) to address the difficulty of using existing complex KTE/KMb models to monitor the impact of large collaborative research networks involving multiple partners and research institutions. To illustrate, the team applied the framework to Promoting Relationships and Eliminating Violence Network (PREVNet), a pan-Canadian community-university network that mobilizes knowledge on bullying prevention and the promotion of healthy relationships among children and youth.

The framework draws on a logic model and incorporates the iterative aspects of prior circular and cyclical KTE/KMb models to show sustained engagement between researchers and partners. The central overlapping space is where co-production occurs throughout the process with illustrated benefits for both researchers and partners at each stage. Engagement is maintained from research development to impact, as well as to inform new research questions and knowledge. The logic model allows for metrics at each of the 4 stages for evaluation:

- Dissemination moves research into practice and policy settings where it can progress towards impact (e.g., press releases, clear language summaries, social media, meetings);

- Uptake occurs when an organization looks to determine whether the research knowledge is useful for informing decisions. Activities may include staff meeting presentations, internal evaluation, and comparisons to literature and existing practices;

- Implementation is when the knowledge is used to inform decisions, such as improved policies and practices; and

- Impact refers to the effect that the research-informed policies or practices have on end users as measured by the partner (e.g., improved health).

permission from Phipps et al. (2016)

Ward (2017): “I Want to Help [WHO] to Mobilize [WHAT] by [HOW] in Order to [WHY]”

To help guide knowledge mobilizers and increase clarity and understanding amongst the diverse and fragmented literature, Dr. Vicky Ward (2017) created a simple framework for thinking about KTE/KMb based on a review of 47 KTE/KMb models. The framework consists of four questions, with common potential responses based on the literature:

- Why mobilize knowledge?

- To develop local solutions to practice-based problems

- To develop new policies, programs and/or recommendations

- To adopt/implement clearly defined practices and policies

- To change practices and behaviours

- To produce useful research/scientific knowledge

- Whose knowledge?

- Professional knowledge producers (e.g., researchers, academics, evaluators)

- Frontline practitioners and service providers (e.g., health and social care professionals, teachers)

- Members of the public and people in receipt of services (e.g., community groups, charities, service user groups)

- Decision makers responsible for commissioning services and/or designing policies and strategies (e.g., policy makers, commissioning managers)

- Product and program developers responsible for designing, producing, and/or implementing products, services, or programs (e.g., service providers, operational managers)

- What type of knowledge?

- Scientific/factual knowledge (i.e., research findings, quality and performance data, population data and statistics, and evaluation data)

- Technical knowledge (i.e., practical skills, experiences, and expertise)

- Practical knowledge (i.e., professional judgements, values, beliefs, and intuition)

- How is knowledge mobilized?

- Making connections (e.g., establishing networks, brokering relationships between users and producers)

- Disseminating and synthesizing knowledge (e.g., online databases, communication strategies, evidence synthesis services)

- Facilitating interactive learning and co-production (e.g., participatory research, action learning)

Health Equity and KTE/KMb Models

Davison et al. (2015) conducted a scoping review to identify KTE/KMb models and evaluate their usefulness for promoting health equity. They identified a total of 48 unique models or frameworks published between 1997 and 2015. Each model was assigned a rating based on 6 characteristics identified as important for supporting health equity:

- A specific focus, mention or consideration of equity, equality, justice, disadvantaged or vulnerable groups;

- An inclusive conceptualization of knowledge (beyond scientific research) that ensures that different types of knowledge and/or ways of knowing might be considered in the evidence base;

- Community members are represented and/or community participation is an explicit part;

- Interactions are supported across disciplines or sectors;

- Specifically refers to the social, physical, political, and/or economic context of knowledge generation and use; and

- Has an applied, proactive, or problem-solving focus.

None of the included 48 models scored perfect on all six characteristics. Low scoring models were most often lacking attention to a multisectoral approach. However, there were some promising approaches identified that could be enhanced to further support equity.

The highest scoring model was the Knowledge Brokering Frameworks by Oldham and McLean (1997), which proposed 3 frameworks for thinking about Knowledge Brokering:

- The Knowledge System Framework relates most closely to private sector knowledge managers, in which knowledge brokers facilitate how knowledge is created, diffused, and used by various institutions and their interactions;

- The Transactional Framework views knowledge brokers as linkage agents, focused on the interface between “creators” of knowledge and organizations that are “users” of knowledge in the context of specific “transactions” (i.e., relevant to specific decisions or projects); and

- The Social Change Framework focuses on building capacity and potentially leading to positive social outcomes, where knowledge brokers enhance access to knowledge by providing training, such as when the users of knowledge are members of the general public.

From an equity perspective, strengths of this model were that it supported an inclusive conceptualization of knowledge, prioritized engagement of a variety of stakeholders, had a strong emphasis on contextual factors as important health and health equity determinants, and discussed how the use of a social change framework could help address power differentials.

The second highest scoring model was the KTE with Northern Aboriginal Communities by Jardine and Furgal (2010). Noted strengths of this model included the establishment of partnerships and trust with and among community members, an inclusive conceptualization of knowledge, the undertaking of capacity development activities, meaningful and prolonged engagement of communities in all research stages, and a sensitivity to contextual factors. In two participatory action research projects, Jardine and Furgal (2010) reconfirmed the importance of spending time developing relationships and trust among all research partners through regular face-to-face, interpersonal contact in order to instill confidence in the researchers and projects, and address the suspicions fostered by previous inappropriately conducted research in the north. They identified five components as fundamental to the KTE/KMb in their study:

- Establishing partnerships and trust with the communities;

- Using trained community field workers/researchers for all stages of the research;

- Holding regular workshops for all members of the research team, which enabled a true two-way exchange of knowledge and mutual learning environment;

- Making a commitment to return the research results to the participants and communities first, for verification and validation; and

- Translating the research results for government decision-makers so that they might be used to inform policy and practice.

Please go to Chapter 2: Data for Equity? for more information about this topic.

Summary

The examples presented in this section represent a select sample of the numerous KTE/KMb models, theories, and frameworks in what has been referred to as a “KT swamp”. Common across many models and frameworks is the understanding of the KTE/KMb process as a collaborative one that involves multiple, dynamic, and iterative steps. They emphasize the importance of tailoring and targeting messaging to audiences, adapting knowledge and strategies to the context, and engaging and establishing partnerships with next users. Many models also highlight the importance of evaluation, which is covered in Section 4: Other Key Considerations. Next, we will discuss specific strategies for disseminating and exchanging knowledge.

Test Your Knowledge

Complete the following activity to assess how much you learned about the content that was covered in this section.

The many activities that contribute to the relational, iterative, and context-sensitive process of moving of knowledge to action, including the synthesis, dissemination, exchange, and application of knowledge.

Situating knowledge procedures and users in a system of knowledge that is responsive, adaptive, and unpredictable (Graham et al., 2006).

A common tool used in program and intervention planning, implementation, and evaluation to visually depict processes, or chains of events, including activities and expected outcomes.

The potential audience of created knowledge.

Achieving parity in policy, process, and outcomes for historically and/or currently underrepresented and/or marginalized people and groups while accounting for diversity (The University of British Columbia, n.d.).

The interrelated conditions in which something exists or occurs (Merriam-Webster, 2022).

The middle people or intermediaries who facilitate interactions between knowledge creators and next users - or researchers and decision makers.

Individuals, organizations, or communities in which next users and researchers are situated and that may be indirectly affected by research (Jull et al., 2019).

A dynamic and iterative process that includes synthesis, dissemination, exchange, and ethically sound application of knowledge to improve the health of Canadians, provide more effective health services and products, and strengthen the health care system (Canadian Institutes of Health Research, 2012, p. 1).

The synthesis, exchange, and application of knowledge by relevant stakeholders to accelerate the benefits of global and local innovation in strengthening health systems and improving people’s health (World Health Organization, 2005, p. 2).