Section 2: Health Systems, Equity, and Population Health Management

LLana James; Dr. Robyn K. Rowe; and Dr. Robert W. Smith

Section Overview

The purpose of this section is to unwind a thread of health policy history that may help explain where current interest in designing equitable health systems comes from. We spotlight Population Health Management as an approach being increasingly adopted within health systems in North America.

Section Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain a few important policy moments and ideas from which Population Health Management emerged;

- Describe the key components and aim of Population Health Management; and

- Identify strengths and limitations of Population Health Management as an approach to creating equitable health systems.

Background

Today, it is more common to see governments and health organizations include “health equity” or “population health” as key goals for their work.

This shift has catalyzed over many decades by civil rights and Indigenous Peoples’ rights activism, advocacy, and most recently by movements, such as Black Lives Matter and Every Child Matters, as well as tragedies, like the murder of George Floyd by police in Minneapolis and uncovering of children’s remains buried in unmarked graves at former Canadian Indian Residential School sites (Bailey et al., 2020; Hahn et al., 2018; Lavoie et al., 2016; Richardson & Boozary, 2021).

If we rewind 20 years, there were a few important health policy moments that also help explain how Population Health Management has emerged as a strategy for making health systems more equitable.

Population Health Policy Moments

Six Domains of High-Quality Health Care

In 2001, the Institute of Medicine published the “Crossing the Quality Chasm” report, which defined “equitable” as one of six core domains of high-quality health care (Institute of Medicine, 2001).

Unequal Treatment

In 2003, the Institute of Medicine published the “Unequal Treatment” report led by Drs. Brian D. Smedley, Adrienne Y. Stith, Alan R. Nelson, and colleagues (Institute of Medicine, 2003b). This report detailed the substantial and long-standing health inequities experienced by peoples made racialized in the United States due to racist beliefs, behaviours, law, and policy shaping peoples’ opportunities for optimal health, access to health services, and experiences receiving care. Among the report’s key recommendations for reducing inequities was collecting data on race and ethnicity and monitoring health system performance and population health outcomes in relation to these data.

Having data on patient and provider race and ethnicity would allow researchers to better disentangle factors that are associated with health care disparities. In addition, collecting appropriate data related to racial or ethnic differences in the process, structure, and outcomes of care can help to identify discriminatory practices, whether they are the result of intentional behaviors and attitudes, or unintended – but no less harmful – biases or policies that result in racial or ethnic differences in care that cannot be justified by patient preferences or clinical need. Data collection and monitoring, therefore, provides critically needed information for civil rights enforcement. (Institute of Medicine, 2003a, p. 215-216)

Accountable Care Organizations

Also in the early 2000s, interest was growing in health system reforms that bring hospitals, physicians, and non-physician health service providers together to work in collaboration with shared responsibility for financial and health service outcomes for a defined population; these would later become known as Accountable Care Organizations (Tu et al., 2015; Wilson et al., 2020).

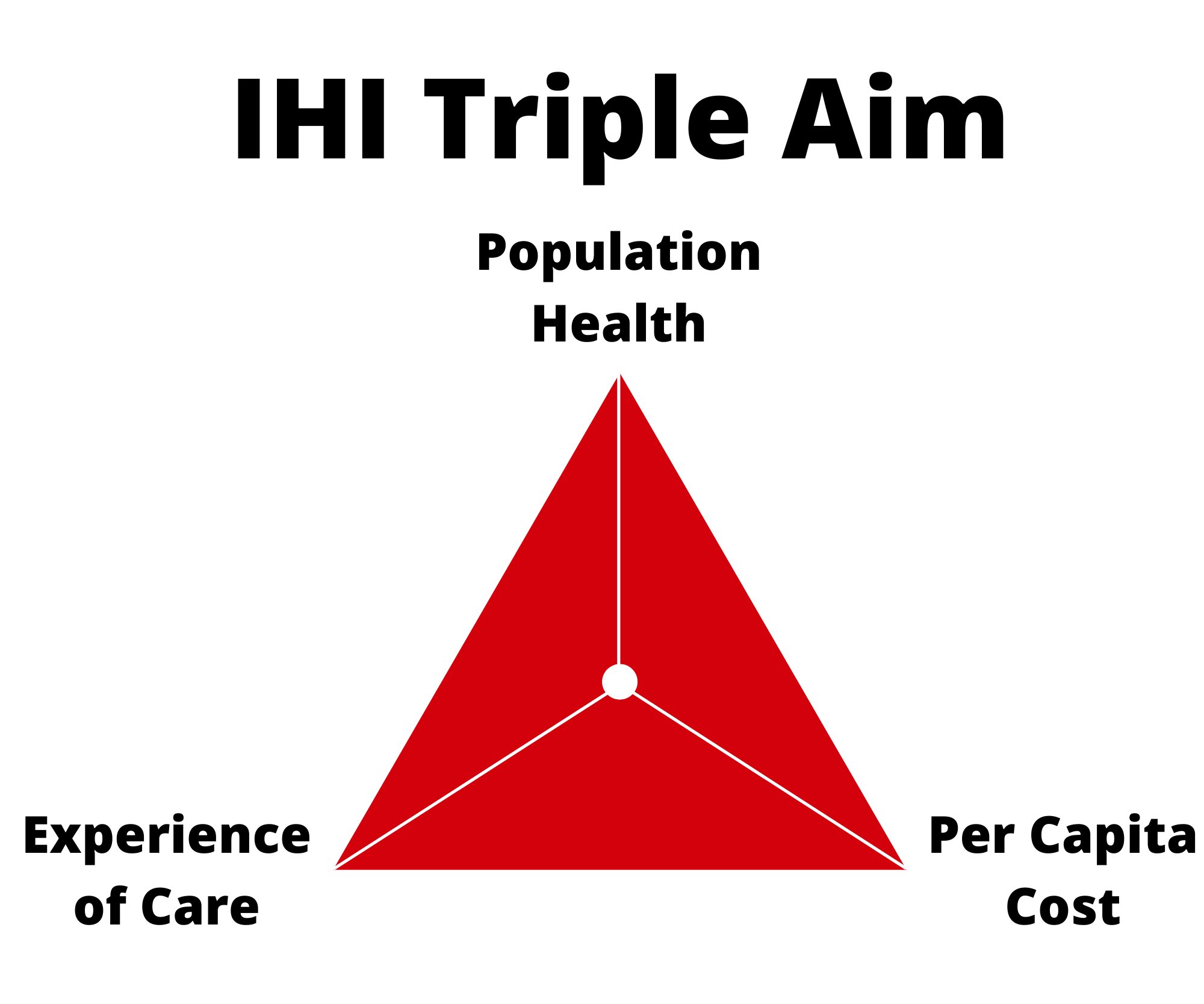

The Triple Aim

An issue with the six domains of high-quality health care was that it only applied to people already receiving services for their health concerns. This prompted reflection on what people who are not yet seeking health care should expect of their health systems.

In 2008, Dr. Don Berwick and colleagues (2008) coined “The Triple Aim.” This concept introduced three fundamental goals for health systems, to simultaneously:

- Promote and protect the population’s health;

- Improve the experience of health care; and

- Reduce the cost of health care.

QUICK SIDENOTE: Population Health Without Equity?

Some scholars suggest the aim of “population health” is problematically vague since the goal of equity is not explicitly included (Lantz, 2019; Nundy et al., 2022). Furthermore, “population” may be used to describe a narrow group of people (e.g., people living with heart failure) instead of every community member living in a geographic area, or whole societies (Lantz, 2019).

These distinctions are important because while a population’s health may on average be improving, health benefits may be concentrated among a privileged few. For example, a large study by Shahidi et al. (2020) recently found that:

Canada has made no overall progress toward the goal of reducing socioeconomic inequalities in premature and avoidable mortality. In fact, the strength of the association between socioeconomic status and mortality appears to have increased substantially between 1991 and 2016. (p. E1126)

Check out the video below from the Institute for Healthcare Improvement on the Triple Aim and the social determinants of health:

So, how does a health system achieve this population health aim?

Today, Accountable Care Organizations and health systems across North America are developing approaches to what the Institute of Healthcare Improvement call Population Health Management (Fraze et al., 2016; Hacker & Walker, 2013; Institute for Healthcare Improvement, 2022; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2019; Waddell, Reid, et al., 2019).

Population Health Management

There is no universal definition for Population Health Management, but it can be described as processes within health organizations that use data on the people they serve to:

- Measure health status, unmet health and social needs, and health care experiences and outcomes;

- Group patients or community members according to health and social and demographic characteristics, health care use, or likelihood of needing health care in the future;

- Proactively design and advocate for services and policies that promote health, prevent disease, reduce inequities, and improve health care outcomes; and

- Implement changes and evaluate whether they are leading to improved health or health care outcomes in a population (Primary Health Care Performance Initiative, 2018; Social Care Institute for Excellence, 2018; Waddell, Reid, et al., 2019).

Check out the video below, specifically between 8:22-21:00 minutes, where Dr. Rob Reid, Chief Scientist of Trillium Health Partners’ Institute of Better Health, describes core concepts of Population Health Management in Ontario:

QUICK SIDENOTE: Other Health Sectors Performing These Roles?

Population Health Management roles have similarities with what the World Health Organization call “Essential Public Health Operations”, such as population health surveillance and health promotion. These have traditionally been performed by Public Health Departments, local Public Health units, or public health professionals working in government and non-governmental organizations, municipalities, and health care organizations (Hacker & Walker, 2013; World Health Organization – Europe, 2022).

A key difference between public health and health care sectors is that public health tends to focus on promoting and protecting the health of society and preventing disease and injuries before treatment is required, whereas health care providers (e.g., primary care, hospitals, long-term care) primarily provide treatment in response to individuals’ immediate health needs.

A core idea within Population Health Management is that collecting better data on patients, community members, and the environments where they live (e.g., race and ethnicity, income, housing, food availability, transportation infrastructure, and policing), improving how this data is analyzed, and acting on the knowledge developed through analysis, will help health system leaders understand the populations they serve, and will equip them with tools for identifying and addressing health inequities.

To date, various Population Health Management approaches have been developed (Butler et al., 2020; Fraze et al., 2016; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2019). Health Care Hot-Spotting is one popular example.

Below is a short documentary describing how Dr. Jeffrey Brenner and the Camden Coalition of Healthcare Providers used hospital billing data, zip codes, and other social and demographic data to identify and respond to “hot-spots” or patterns of increased health care use by neighbourhood. Using information generated from the data, the Camden Coalition team, which includes social workers, doctors, nurses, and other service providers, developed a holistic model of health care. That means that patients receive services and support accessing services that address their physical and mental wellbeing as well as social conditions (e.g., financial support programs, affordable food and housing, legal aid). In this video, Dr. Atul Gawande interviews Dr. Jeffrey Brenner, Camden Coalition team, and community members supported with long-term health and social services at home in an effort to improve health and prevent avoidable hospitalizations:

Cautionary Notes

It is important to note that it remains unclear whether social and demographic data collection within health care organizations itself leads to actions that address health inequities (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2019).

Developing effective and equitable change within health systems is challenging not least because of the time, people, knowledge, funding, and equipment (e.g., data collectors, analysts, information systems) required for, and the complexity of:

- Collecting and collating robust health, social, and demographic data, then;

- Conducting rigorous analyses informed by seminal theory, ethics, and a comprehensive understanding of existing scientific evidence, then;

- Translating this knowledge into health service design, then;

- Implementing effective and equitable models of care.

Indeed, a major randomized controlled trial found no statistically significant effect of the Camden Core Model on risk of returning to hospital, length of hospital stay, or health care costs within six months of discharge (Finkelstein et al., 2020). Other models designed with similar intentions have also produced null or mixed results (Berkowitz & Kangovi, 2020; Iovan et al., 2019; Purnell et al., 2016).

Furthermore, whether or how action is taken among policy makers and health system administrators to address inequities also depends in part on the priorities, world views, and power relationships of individuals and organizations gathering and/or responding to inequities identified using data (Lorenc et al., 2014; McGill et al., 2015; Petticrew et al., 2004; Smith, 2014; Turner et al., 2013; Whitehead et al., 2004).

Finally, it’s important to remember that even the act of collecting social and demographic data in health settings and sophisticated analyses that follow can cause harm to community members.

Deeper Dive

- Harvard Data Science Initiative Bias^2 Seminar on racial bias coded into a machine learning algorithm used to determine who gets certain types of health care (Obermeyer et al., 2019): https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.aax2342

- Commentary on harms and opportunities to improve screening for unmet social needs in health care (Butler et al., 2020): https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.19.1037

- Medical apartheid: The dark history of medical experimentation on Black Americans from colonial times to the present (Washington, 2006)

Ethical Engagement of Black Communities in Data Collection and Evaluation Processes

To support community members, learners, health system workers, and researchers with avoiding harmful and unethical data collection, research, and evaluation with Black communities in Canada, LLana James and Dr. Ciann L. Wilson are launching the REDE4BlackLives Research, Evaluation, Data Collection, and Ethics Protocol for Black Populations in Canada (James & Wilson, 2020).

James and Wilson (2020) state that the objectives of REDE4BlackLives are to:

- Build upon our growing interdisciplinary and multi-sectoral collaborative partnerships;

- Craft and implement a research, evaluation, and data collection protocol to guide the ownership, control, access, and sharing of information about Black individuals and communities collected for the purpose of research, evaluation, and community engagement; and

- Assist Black communities in Canada, researchers, evaluators, data collectors, scientists, policy makers, funders, and donors in public, private, and public-private initiatives, partnerships, collaborations, and/or organizations to think through the nuances of conducting ethical and beneficial research, evaluation, and/or data collection with and for Black communities.

Ontario Health System Reform

In 2019, the Government of Ontario announced plans for substantial health system reforms that involve:

- Bringing six provincial health agencies and 14 Local Health Integration Network agencies under one roof–within the new Ontario Health “super agency” (Waddell, Wilson, et al., 2019);

- Creating Ontario Health Teams, which are networks of health, social, and other service providers that work together to deliver services that span the care continuum, and share responsibility for a defined patient population (Ministry of Health, 2019); and

- Consolidating 34 local Public Health Units into 10 regional public health agencies – however, these plans were subsequently put on hold due to the COVID-19 pandemic (Smith et al., 2021).

When fully up-and-running, Ontario Health Teams may look and function like Accountable Care Organizations (Waddell, Wilson, et al., 2019). Population Health Management is already being introduced to Ontario Health Teams as a mechanism for identifying and addressing health care and population health inequities (Waddell, Reid, et al., 2019).

When this is considered alongside Ontario Health’s mandate to “[improve] how the agency uses data in decision-making, information sharing and reporting, including by leveraging available and new data solutions…” (Ministry of Health, 2021, p. 3), it may be reasonable to suggest that data collection, analytics, and sharing are foundational components of the Ontario health system’s strategy for reducing health inequities.

Take a moment now to read the following case study, which gives a local example of some of the changes taking place in Ontario, Canada.

CASE STUDY: Trillium Health Partners and AI for Population Health

Born in 2012, Trillium Health Partners (THP) is among the largest community-based hospital systems in Canada serving a population of around two million people (Trillium Health Partners, 2019). It operates on the traditional territories of the Mississaugas of the Credit, the Anishinabek, Huron-Wendat, Haudenosaunee, and Ojibwe/Chippewa peoples in what is now called the Region of Peel, Ontario. Peel Region’s geography remains home to vibrant communities of Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples from many nations and speaking over 133 languages (Trillium Health Partners, 2019). However, many communities are also experiencing growing income insecurity (Dinca-Panaitescu et al., 2017).

In their 2019-2029 strategic plan, THP states: “Our mission to build a new kind of health care for a healthier community means discovering the potential of better health for all” and their strategic priorities are to:

- Deliver high-quality care and exceptional experiences;

- Partner for better health outcomes; and

- Shape a healthier tomorrow.” (Trillium Health Partners, 2019, p. 24)

To shape a healthier tomorrow, “THP will embark on several major investments…including: building capacity for the future; adopting new technology and sharing information across the community and beyond; and, strengthening the broader network, or ecosystem, that influences the health and prosperity of the community.” (Trillium Health Partners, 2019, p. 52)

The Institute for Better Health is THP’s innovation and research arm which is “focused on generating cutting-edge science and innovation in health service delivery and population health.” THP and the Institute for Better Health are making unprecedented changes to its information systems and leverage artificial intelligence technology with the goal of improving health care.

- October 2020: THP overhauls its electronic medical record (EMR) system purchasing the Epic EMR developed by a major American vendor called Epic Systems Corporation (Laugheed, 2019; Trillium Health Partners, 2022).

- October 2021: Institute for Better Health announces the adoption of cloud-based technology for predicting hospital bed occupancy developed in partnership with the University of British Columbia and Amazon World Services (Trillium Health Partners, 2021).

- November 2021: THP attracts a $1 million donation from TD Bank Group and establishes the Health Care AI Deployment and Evaluation Lab (Trillium Health Partners Foundation, 2021).

Hypothetical Scenario:

To realize its priorities and implement population health management, THP in partnership with Mississauga Ontario Health Team, explore ways to expand social and demographic data collection, to develop AI algorithms that can identify unmet social needs (e.g., income insecurity) from patient medical histories written in EMR notes, and collate data from various sources for analysis using its cloud-based platform.

Reflection Question:

What are some potential benefits and risks of using EMRs for sociodemographic data collection and AI and cloud-based analytics for population health management?

Summary

Wider recognition of the role that health systems play in preventing and perpetuating health inequities is a positive development for health policy in recent decades. There are many ways health systems can approach enacting espoused values of health equity. Population Health Management is a concept and evolving collection of approaches that emphasize data analytics as a tool for realizing health equity. As Population Health Management enters the Ontario health system, it is essential that health service providers, administrators, and policy makers carefully consider the complexities and potential harms of these approaches. Work involving the collection, analysis, and evaluation with communities made marginalized by racism and intersecting forms of oppression should be guided by ethical protocols developed through deep engagement with community members. Indigenous Data Sovereignty is another key area that learners need to understand firmly when approaching or being approached by this type of work. For more on this, proceed to Section 3: Indigenous Data Sovereignty.

Test Your Knowledge

- What are two strengths of having “health equity” as an explicit aim of health systems versus “population health” alone?

- What is Population Health Management?

- Does the collection of social and demographic data in health care settings guarantee action will be taken to address identified health inequities? Why or why not?

- What are three risks related to the collection and analysis of social and demographic data in health care settings?

Processes within health organizations that use data on the people they serve to:

1. Measure health status, unmet health and social needs, and health care experiences and outcomes;

2. Group patients or community members according to health and social and demographic characteristics, health care use, or likelihood of needing health care in the future;

3. Proactively design and advocate for services and policies that promote health, prevent disease, reduce inequities, and improve health care outcomes; and

4. Implement changes and evaluate whether they are leading to improved health or health care outcomes in a population (Primary Health Care Performance Initiative, 2018; Social Care Institute for Excellence, 2018; Waddell, Reid, et al., 2019).

The right of Indigenous Peoples to own, control, and use Indigenous data (Rainie et al., 2019).