Section 2: Frameworks for Improvement

Dr. Madelyn P. Law; Dr. Elaina Orlando; and Lidia Mateus

Section Overview

In this section, we present a breakdown of frameworks that are used to implement evidence-based changes in health organizations. Interestingly, these frameworks often overlap, are conceptually intertwined, and can be used together to inform processes to achieve the change that is desired.

Section Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Identify and critically assess frameworks and their application to various health sector contexts that support organizations and individuals in their efforts to make evidence-based changes;

- Differentiate between the formative and summative approaches to change and critically assess how they should be applied; and

- Understand the elements of these approaches and how they are operationalized in practice.

Test Your Knowledge

Complete the following activity to assess how much you already know about the content that will be covered in this section.

Overview of Formative and Summative Frameworks

There are many different frameworks that exist to support evaluation and the use of evidence to inform decision-making in the health sector and in other industries. To help streamline thinking and support one’s decision on what framework to choose and use, we have organized them into three groups: formative, summative, and guiding frameworks.

A formative framework is one that allows for formative evaluation to occur throughout a change effort in a rapid way. Real-time changes can then be incorporated into the project or intervention to respond to challenges or unintended outcomes that may be encountered throughout implementation. This approach relies strongly on data at baseline, constant measurement, and use of data to understand and modify the approach. For example, using the formative approach of the Model for Improvement (described below), we would develop a patient discharge form together with practitioners and patients which is then trialed and reviewed after being implemented on one unit with a few patients. The information from this trial is then used to improve the processes related to the implementation and then trialed again. This cycle would continue until it has been refined and reaches a stable state that is achieving the desired improvements. This constant use of data helps to direct the next steps, all with the goal of enhancing the processes to affect the outcomes. These formative evaluation features, in theory, would help to support more effective and successful implementation of health innovations (Elwy et al., 2020), given the ongoing attention and iterative approach to improvement.

Summative frameworks, on the other hand, are those that allow for evaluation at the end of an implementation. This summative evaluation allows one to understand if something did or did not work at the end of a specified time or the end of the implementation. Often the focus is to examine the impact or efficacy of a program once it is in a stable condition. If you are a student, one example of this is the end-of-term course evaluation that you fill out. In a health setting, this could come in the form of an evaluation of data related to smoking rates after the implementation of the Smoke-Free Ontario Act, which prohibits smoking and vaping in enclosed workplaces in Ontario (Public Health Sudbury, 2021). Reviewing data on how this helps to reduce smoking rates would be an example of a summative evaluation.

Both approaches are important. They are not mutually exclusive. For example, there were numerous changes to processes, because of formative evaluations, to the roll-out and implementation of strategies to help organizations align to the Smoke-Free Ontario Act (e.g., improving awareness campaigns, enhancing signage, etc.), with the summative evaluation being smoking reduction. That said, relying only on one is not ideal. Simply evaluating a project in the end can be a waste of resources and effort if within a week or month the intervention is simply just not working. Why wait for the program funding at the end of 6 months to make changes? Having a formative mindset is important at the outset of a program, service, or policy creation to ensure that things are working throughout.

There are numerous formative and summative frameworks that have been developed and described in the literature and mainstream reading to support this complex notion of making change. As the purpose of this book is to provide a foundational understanding of the use of evidence to drive health sector improvements, we have summarized some of the main frameworks and approaches that we have encountered in practice and in the literature. Next, we provide you with an overarching understanding of guiding frameworks, including the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) and the Practical, Robust Implementation and Sustainability Model (PRISM). These are two commonly used frameworks that outline factors to think about before, during, and after implementing a change.

Guiding Frameworks

Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR)

When looking to implement novel changes into any organization, including health care, it is important to truly understand the context in which these changes will be made. The CFIR is a conceptual framework based on previous literature that has identified aspects that influence the implementation of interventions. This framework can be used by individuals to assess potential issues so that mitigating strategies can be developed, used as a framework to assess current barriers within implementation, or to evaluate the contextual reasons for successes or failures in a particular intervention.

From an implementation science lens, this framework can be used to study and understand common factors that influence uptake and adoption of the interventions to help further the science while organizations can examine their own context and data to understand how to foster quality improvement.

The CFIR includes five broad categories that are said to influence implementation (CFIR, 2022). These include:

Now that is a long list! It is important to consider these five domains at any level of implementation.

Deeper Dive

- Check out the CFIR website to see how each of these domains is defined. This website provides an overview of the foundational work that was used to create the CFIR, together with definitions, recent articles, and tools and templates: https://cfirguide.org/constructs/

Using the CFIR allows an organization to think about the factors that are influencing their change efforts and subsequently address these factors through change strategies.

This video interview below provides a great overview of the CFIR from Laura Damschroder, one of the authors of the framework. She outlines what implementation science is in relation to quality improvement as well.

An example of where the CFIR has been used in a way to support rapid-cycle evaluation for improvement is found in this article by Keith et al. (2017). Keith and colleagues incorporated the CFIR into the launch of a Comprehensive Primary Care initiative in the United States, which was a four-year program with the goal of strengthening primary care to improve health, lower costs, and enhance the patient and provider experience. The project team interviewed core personnel and asked about their experiences of how components of Comprehensive Primary Care were operationalized in practice, as well as challenges and support for implementation. They also engaged in direct observations with a checklist that was based on the five CFIR domains. This was a large-scale change project spanning multiple years and areas in the United States, and the CFIR was effective at supporting the identification of areas for improvement, making refinements, and sharing this information across sites to enhance learning.

Formative Evaluation

Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance (RE-AIM) Framework

RE-AIM is the acronym for Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance. As one of the most widely used implementation frameworks (Glasglow et al., 2019), the RE-AIM framework has a long-standing 20-year history in health care and health promotion. The framework was first published in 1999 by the American Journal of Public Health, reflecting the importance placed on understanding issues related to implementation and the lack of adoption of effective interventions by organizations (Gaglio et al., 2013). The framework was initially developed to understand the internal and external validity of interventions and programs with a more summative type of approach. The RE-AIM framework is somewhat like the CFIR in that it can be used to evaluate an existing program, or in the planning stages of an intervention, to highlight aspects that should be considered. Authors have suggested that it should be considered for a more iterative application to support the work done at the implementation phases of an intervention (Glasglow et al., 2019).

Below is an overview of each of the dimensions of the RE-AIM framework:

The video below of Dr. Russ Glasgow provides an overview of the history and the next steps of the RE-AIM framework:

Many examples of the use of the RE-AIM framework can be found in the literature. One recent paper describes the summative use of RE-AIM to evaluate a collaborative care intervention to treat primary care patients with comorbid obesity and depression (Lewis et al., 2021). This project incorporated qualitative interviews at various time points of the project with core stakeholders, which were then compared back to the dimensions of the RE-AIM framework to identify the programs’ translational potential for public health impact in future implementations. Using RE-AIM, the project leads identified the importance of more flexible scheduling and the need for more diverse and broad recruitment in the clinical setting (Reach), a need to tailor the program components (Effectiveness), the importance of focusing on creating buy-in across the clinical settings to enhance uptake (Adoption), the need to map workflow and align communications (Implementation), and the need to address concerns about cost-effectiveness (Maintenance). The authors anticipated that by addressing these areas for improvements, the program would achieve its intended health outcomes for patients.

Practical, Robust Implementation and Sustainability Model (PRISM)

PRISM is yet another model that helps to support thinking related to moving research to practice. This framework allows for the understanding of the impact of internal (organizational characteristics) and external influences on the implementation of a change with consideration of these aspects at various times throughout the implementation. As outlined by McCreight et al. (2019), this framework has a multi-level lens that combines the Diffusion of Innovation, the Model for Improvement, and the RE-AIM framework. The extension of this theory is that it emphasizes fit within the context and understanding of strategy and outcomes and their importance to implementation and sustainability. McCreight et al. (2019) have provided an excellent overview of this model and a figure that describes the interacting layers of the intervention, recipients of the change, and the internal environment – all with a lens on how this interacts to support the achievement of outcomes with the RE-AIM framework.

Model for Improvement

Check out the video below from the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) about quality improvement in health care:

The Model for Improvement is a quality improvement model developed in 1996 by Associates in Process Improvement following the work of Joseph Juran, W.E. Demming, and Philip Crosby (Courtland et al., 2009). The model is a method that can be implemented effectively across organizations regardless of size and is centered on producing results that are measurable and specific. The Model for Improvement includes three core questions and a change cycle that are used together with measurement tools and processes to enact change (IHI, 2022a). The focus of this model is formative and is to be used iteratively to effect change during implementation.

The Model for Improvement asks the following questions, which provide direction and focus for the improvement effort (IHI, 2022a; Boland, 2020):

- What do we want to accomplish?

- How do we know that a change is an improvement?

- What change can we make that will result in improvement?

The first question, “What do we want to accomplish?”, is addressed by creating an aim statement. This is a statement that outlines the expected outcomes of the change effort. It should be time specific, measurable, and define the population or system that will be impacted (IHI, 2022a; Boland, 2020).

The second question, “How do we know that a change is an improvement?”, is addressed by defining the measures to be used for the change effort. Outcome, process, and balancing measures are commonly used to quantify change in the Model for Improvement. Outcome measures reflect the expected outcome(s) and should reflect how the system impacts users (e.g., patients, staff, stakeholders, community members) (IHI, 2022a; Boland, 2020). Process measures reflect the actions being taken to bring about change. They should address the functioning of various parts of the system being changed – if they are performing as planned and if changes are occurring according to schedule (IHI, 2022a; Boland, 2020). Finally, balancing measures reflect the potential impact of the change effort on other parts of the system. They should address potential problems being caused in other parts of the system as a result of the change effort (e.g., inefficiencies, increased workload or strain, patient outcomes, etc.) (IHI, 2022a; Boland, 2020). Data from each of these measures should be plotted over time on a run chart, thereby allowing the team to visualize the pattern of change (IHI, 2017).

The third question, “What change can we make that will result in improvement?”, is addressed by implementing small-scale change concepts. Change concepts are general approaches to change that are specific, actionable, and testable. Commonly used change concepts in a health care setting include improving workflow, managing time, changing the work environment, error proofing, and eliminating waste (IHI, 2022a; Boland, 2020). Change ideas can be identified through current research, best practices, or expertise within the team.

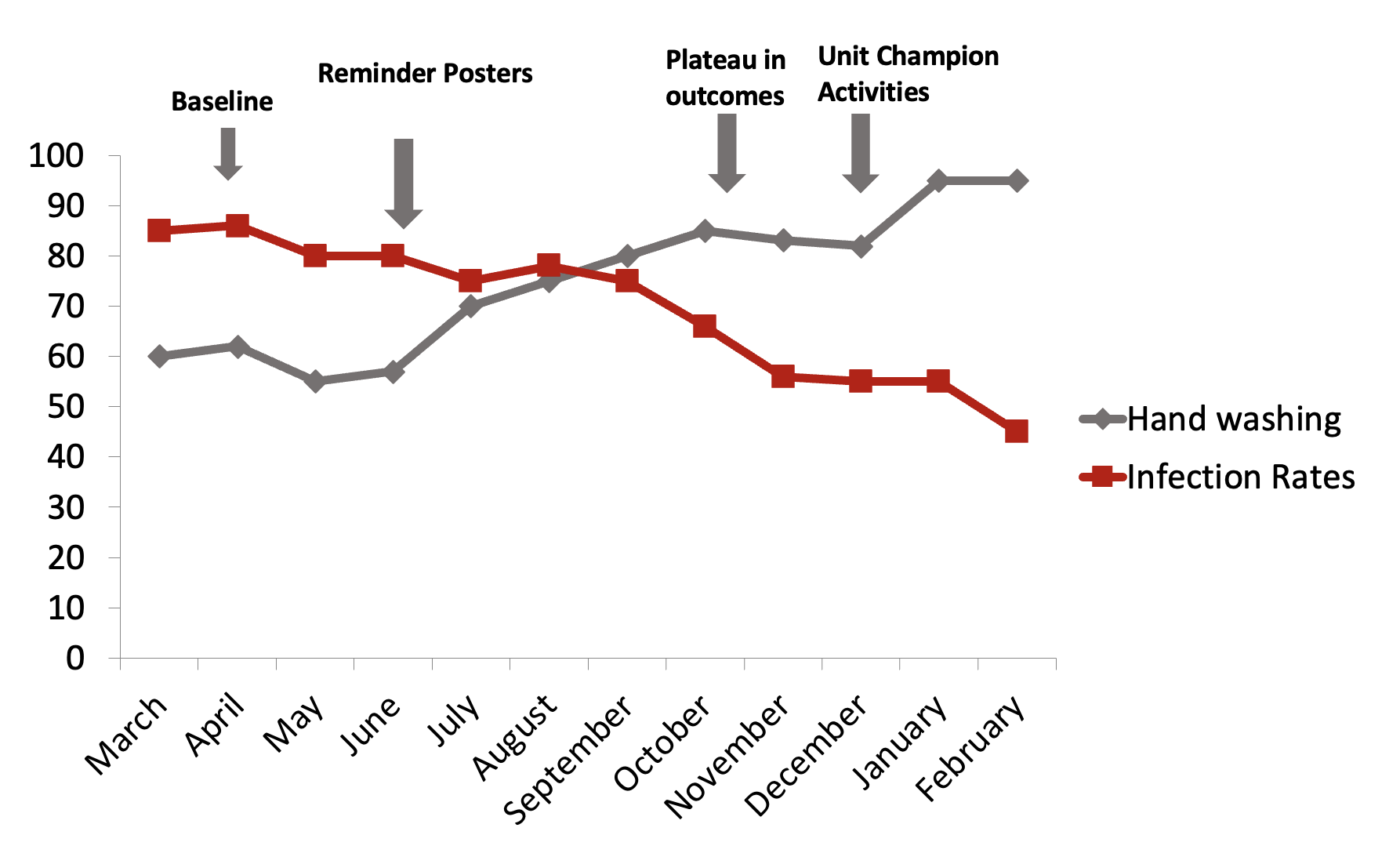

CASE STUDY: Tracking Improvements in Hospital Acquired Infection Rates Over Time

A team of quality improvement specialists at a local hospital is tasked with reducing the rates of hospital-acquired infection and determined that the best way to do this would be to examine and influencing handwashing behaviours. After forming a team, defining the expected outcomes of the change effort (i.e., increased observed hand washing and decreased infection), and developing a plan for change, the team implemented two small-scale changes. First, posters were created to encourage frequent hand washing and placed in high-traffic areas within the target hospital unit (Change 1). Initially, this change resulted in improvement in hand washing and infection rates decreasing over time, but as the team continued to measure infection rates, a plateau was observed. Following this, a second change was implemented, whereby the team used a targeted communications with unit champions through staff huddles and shift change overs (Change 2). The effects of this change on infection rates were tracked over time. Each plot point on the run chart represents data related to the change effort at a specific point in time. Annotations are used to indicate when change efforts were initiated as well as to make note of any external factors that may have affected the change.

Deeper Dive

- For more information about run charts, check out this website: A-guide-to-creating-and-interpreting-run-and-control-charts.pdf (england.nhs.uk)

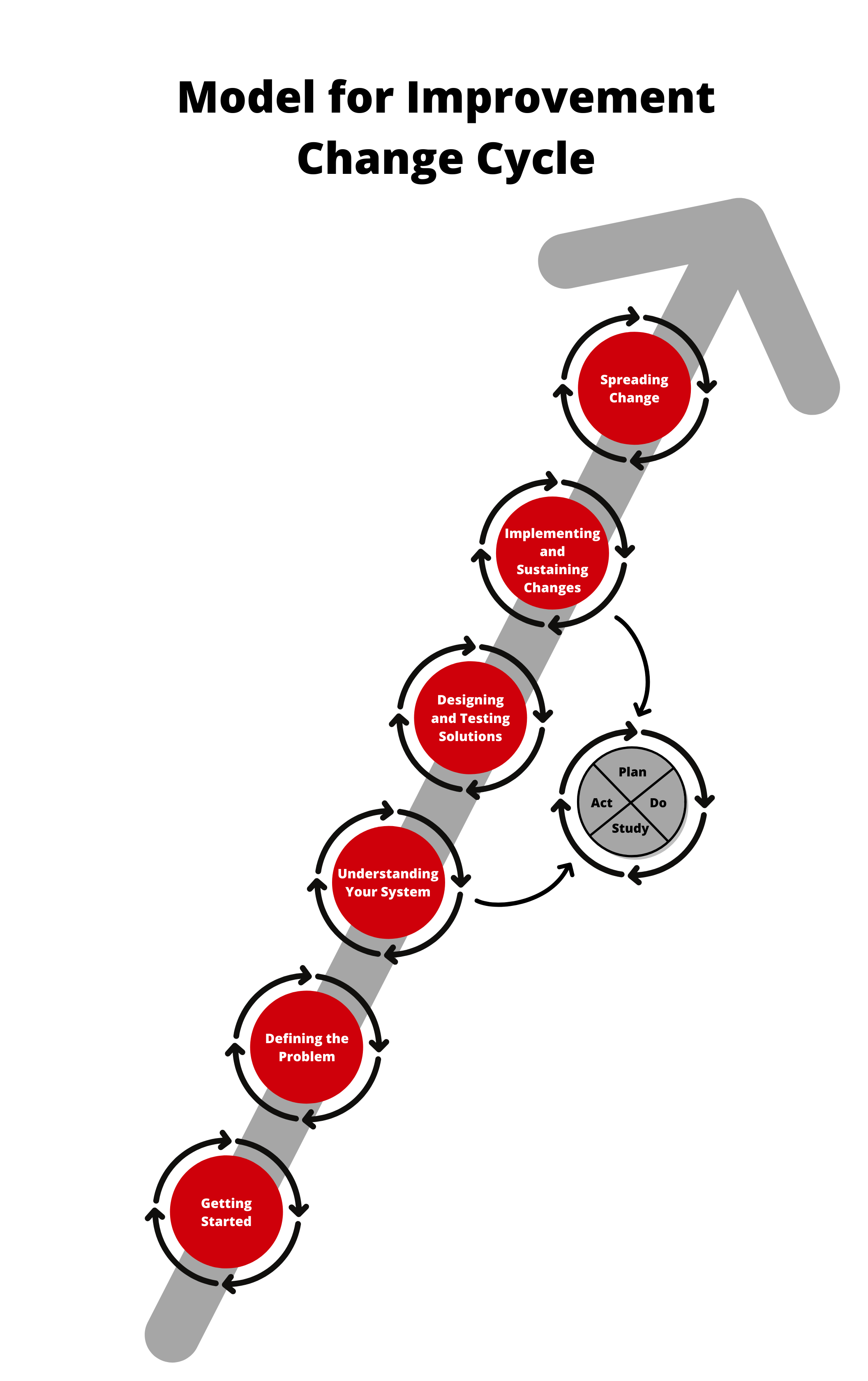

The Model for Improvement Change Cycle is a six-phase iterative process. The “Getting Started” phase involves a team being brought together, identifying areas for improvement, and defining how success will be measured and sustained throughout the process. “Defining the Problem” is the phase in which current processes and underlying problems are clarified. Tools such as the fishbone diagram can be used to identify specific areas for improvement and identify target outcomes. “Understanding Your System” is the phase in which data related to the improvement effort is collected and analyzed. This stage allows for a better understanding of how the system is performing and may further highlight opportunities for improvement. “Designing and Testing Solutions” is an action phase in which change efforts are enacted on a small-scale using Plan Do Study Act (PDSA) cycles. “Implementing and Sustaining Changes”, as the name suggests, is concerned with the long-term uptake and maintenance of a change effort. This phase occurs when the change effort is integrated into daily practice or workflows. Finally, “Spreading Change” involves expanding the change effort between systems, departments, or organizations.

The Model for Improvement Change Cycle relies on PDSA cycles to inform changes in real-time to ensure that the aims of the work are being achieved. This continuous cycle of focusing on the PDSA work ensures that the change is optimized after improvements are made before looking to spread the change more broadly.

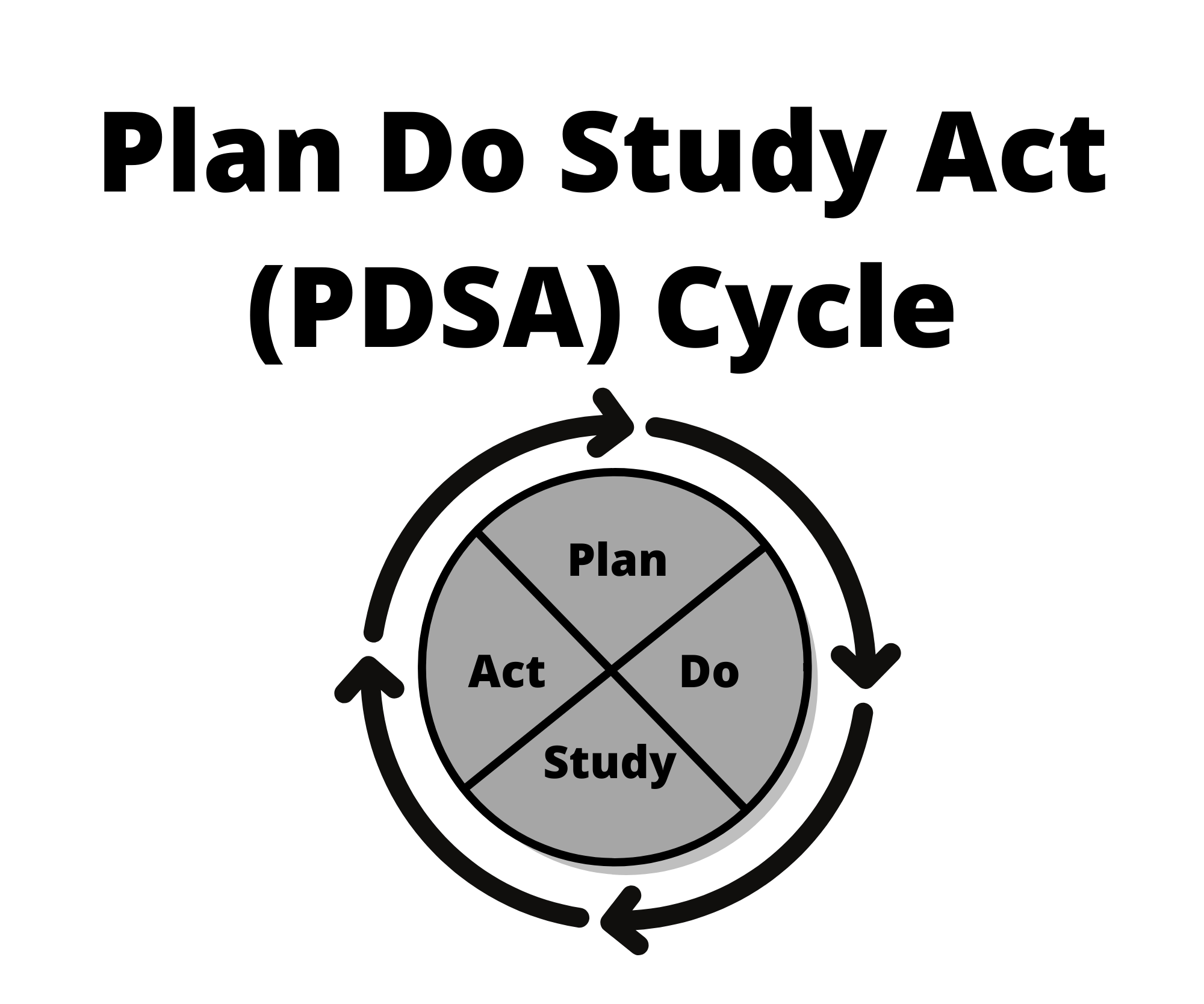

The PDSA cycle is a four-stage rapid cycle used to test a change effort (IHI, 2022b). In the Plan phase, the team should clearly outline the objective of the test (using an aim statement is beneficial), make predictions about the outcome, create a plan to test the change, and determine the data that will be collected. In the Do phase, the team will carry out the test on a small scale – this is important as it is unwise to implement a large-scale change without understanding how it will impact the system (remember the balancing measures!). Documenting observations about the process and beginning to analyze data are key components of the Do phase. In the Study phase, the team will complete data analysis, compare their expected outcomes with the observed outcomes, and outline what was learned from their attempt(s) to implement the change. Finally, in the Act phase, the team will modify the change based on what was learned. A single change effort often goes through numerous PDSA cycles to refine the change being made before applying it on a larger scale.

Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve, Control (DMAIC)

DMAIC is a process improvement methodology that was developed out of the Six Sigma approach to quality improvement (American Society for Quality, 2022b). Six Sigma is a statistical approach to process improvement that is focused on finding the root cause of the variation in a process when the variation is outside what would be considered normal. The name Six Sigma gives you a hint as to what is considered “atypical variation”: anything more than three standard deviations from the mean. If you’re thinking “this sounds technical”, you would be correct! Six Sigma, and for our purposes here, DMAIC, are highly structured and rigorous improvement processes that require both statistical knowledge and accessible, timely, and reliable data. Each letter in the acronym outlines a step in the five-phase improvement process and is associated with specific tools to facilitate improvement. Consult Table 3.1 to learn about the steps and improvement tools that are central to the DMAIC methodology.

| Phase | Definition | Tools |

|---|---|---|

| Define | Define the problem, opportunity for improvement, improvement effort, and specific goals of the project. |

|

| Measure | Measure the current process and identify measures necessary for the improvement effort. |

|

| Analyze | Determine the root causes of non-optimal performance or defects in the process. | Activities

|

| Improve | Eliminate or minimize the root causes identified in previous steps and introduce adjustments to improve the process. | Activity

|

| Control | Manage the newly improved process to sustain performance. |

|

Improving patient flow and efficient access to care is a challenge faced by many Canadian health care organizations. While the solutions are immensely complex in nature, especially for patients needing an inpatient bed, for patients who never get admitted to hospital, perhaps there are opportunities to take a systematic approach to making their emergency department visits more efficient. One of the contributors to a longer emergency department visit is the time a patient may spend waiting for a diagnostic test such as a computerized tomography (CT) scan. This can help determine the plan of care.

If we use DMAIC as our guide, to define the opportunity, we might say our goal is to reduce the turnaround time for a CT scan for non-admitted emergency department patients. We may create a project charter identifying key stakeholders, including physicians, nurses, managers, medical imaging technologists, patients, and families. In this charter, we could also take the time to define some of the nuances to our focus by specifying a type of CT scan (e.g., non-head CT scans only), how frequently we will measure (e.g., weekly), what the specific outcome measure will be (e.g., time from CT scan ordered to CT scan taken), what type of measure we will use (e.g., 90th percentile), and whether we need to divide our measure based on known differences in the context that will knowingly cause atypical variation (e.g., day shift, evening shift, night shift due to different staffing models).

When our interdisciplinary team that is outlined in our project charter has defined some of these specifics, we are ready to go ahead and measure our indicator, plotting it on a control chart that gives us a visual representation of our variation and helps to identify a realistic goal to work toward. By using a control chart, we are also setting up the process of monitoring both improvements and the control process as we work towards our goal.

In the analyze phase, we have multiple options for tools to support us in identifying the contributors to our variation. Using a root cause analysis would help us to uncover if there is a delay in turnaround time because requisitions are not always fully completed before sending them to the medical imaging team. In this case, the requisition gets sent back to the ordering health care professional to be revised and then sent back to medical imaging. As you might have guessed, in a busy emergency department, someone might not always be readily available to make changes to their paperwork, which can lead to notable delays.

In the improvement phase, the interdisciplinary team has the task of determining what actions could be taken to ameliorate some or all the “defects” in the process that were identified in the analyze phase. In this case, we might look to adjust the requisition form to make it easier to complete the necessary components, or in the case of electronic forms, we could institute mandatory fields that would prevent the requisition from being sent until the fields are complete.

The final phase is to control, which is the monitoring phase. Once our improvement(s) have been implemented and identified as effective in achieving our outcome (i.e., reducing turnaround times), we would then monitor our outcome indicator regularly to ensure the change is sustained. Some variation is expected but our control chart will signal to us when the variation is no longer in an expected range. This can indicate that our intervention or change is no longer working or may be a symptom of a new contextual factor that has influenced the process.

Realist Evaluation

Within the context of implementation science, we can consider applying process evaluation methods, formative evaluation methods, or summative evaluation methods. There is however another perspective that researchers and evaluators can consider, and it has relevance in the context of health care: the realist evaluation, which can be applied both in the contexts of the formative and summative evaluations.

Pawson and Tilley (2004) describe the realist evaluation as an approach that considers what works for whom, in what circumstances, in what respects, and how? In essence, the realist evaluation approach contributes to our understanding of the contextual factors impacting the success of an intervention. Salter and Kothari (2014) specifically note that the realist evaluation is best described as a “logic of inquiry” rather than a method or evaluation technique. In health care, when we so often focus on removing all confounding variables, including the participant variability from the equation when testing evaluations, the realist evaluation adds to the literature on implementation science by urging us to acknowledge, embrace, and measure the disruption of an intervention. This can make it challenging for some to embrace or a breath of fresh air in terms of approaches to understanding complex interventions. We’ll use an example of implementing a medication reconciliation process in an acute care organization to depict approaches to a realist evaluation.

The starting point of the realist evaluation approach is the theoretical foundation on which the program or intervention being evaluated has been based (Pawson & Tilley, 2004). This is a common starting point among many types of formal program evaluations. The distinctive feature of the realist evaluation method at this phase is the act of refining program hypotheses using interviews with practitioners about successes and failures of the program or intervention to begin uncovering more contextual hypotheses about what works, for whom, and when. Taking a realist evaluation approach to the implementation of a medication reconciliation process, we would use our intuition to assume that the theory behind the program is that by systematizing the way in which home medications are documented in hospital, we reduce the potential for adverse drug events. We would also interview stakeholders from Safer Healthcare Now! or Accreditation Canada to understand the theoretical bases for the program.

Once you have an understanding of the theory driving your program or practice change, it is important to understand all the activities contributing to your intervention and how they link together (Pawson & Tilley, 2004). When you detail the activities and links, you will start to be able to conceptualize your evaluation questions based on the hypotheses of how the program works in its ideal state. In our example, the activities associated with the intervention of medication reconciliation are numerous, however, we include a couple of them here: developing the standardized home medication documentation form (Best Possible Medication History), educating staff on the roles of the interprofessional team in the process, and aligning practice changes with external partners, such as home and community care, who will support the final transition phase home. The activities all connect through key linkages, such as documentation, education, communication, practice change, and finally, outcomes.

The realist evaluation then moves to a data collection phase, where the multiple hypotheses uncovered and the plethora of evaluation questions linked to your activities begin to be tested (Pawson & Tilley, 2004). Quantitative and qualitative measures are both used. When data has been collected, the researcher or evaluator must then systematically test the initial group of hypotheses, testing various combinations of hypotheses in order to help find patterns that determine successes and failures. This can be an in-depth process when there are multiple activities and evaluation questions to answer regarding the effectiveness of your intervention. In our example, let’s take one specific activity in the intervention and break it down: If we ask, “Is the completion of the best possible medication history on admission to hospital being accurately completed”? To answer just this question, we have several secondary questions linked to it, including: Were more than two sources of information used to determine the medication list?; Was the patient consulted to verify medications (as possible)?; Were dose, strength, and frequency documented for all medications on the list?; Was the list documented accurately (e.g., no missing medications, no duplicate medications, current medications only)? This data might be collected via an audit and tells us a great deal about whether we need to modify the approaches to implementing this aspect of the intervention.

The final stage of the realist evaluation is cyclical as the analysis is interpreted and the hypotheses about mechanisms of program or intervention functioning are assessed and revised (Pawson & Tilley, 2004). The cyclical nature allows continued revision of hypotheses to understand the complex interplay of factors, including context, individuals, and processes, all of which are seen to influence the intended outcome.

As you can see, the realist evaluation requires many considerations, however, the complex nature of health care interventions may warrant approaches like this which offer opportunities to appreciate and adjust for the complex environment and how it interacts with our complex interventions rather than simply trying to control for the inherent messiness!

Summary

You are the practitioner or the researcher and now you are wondering…which of these frameworks and approaches should I consider!? The answer is – it depends! If you are looking to evaluate an existing program or service that you did not create but are tasked with understanding if it is effective – then you can apply a CFIR lens, the RE-AIM framework, or conduct a realist evaluation. If you would like to implement a new change based on new evidence or make an improvement to an existing service or program, then perhaps starting with an analysis of the context with the CFIR followed by the implementation strategies and tools set out by the Model for Improvement would be ideal next steps. The point here is that the framework you choose will depend on your situation, question, and requirements for actions. We hope that this section has provided you with a set of frameworks that resonate with you and a toolkit of information that will enable you to make sure that data can be realized in practice and not simply sit on a shelf for another 17 years.

Test Your Knowledge

Complete the following activity to assess how much you learned about the content that was covered in this section.

Deeper Dive

- For more about CFIR: https://cfirguide.org/

- For more about Six Sigma: https://asq.org/quality-resources/six-sigma

- For more about the RE-AIM framework: https://www.nccmt.ca/knowledge-repositories/search/70

- The following website provides practical and user-friendly information about RE-AIM and PRISM. There is a guide for step-by-step use: https://re-aim.org/

- For more about the Model for Improvement: How-to-Design-Implement-a-QI-Project.pdf (pedsanesthesia.org)

A framework that allows for formative evaluation to occur throughout a change effort in a rapid way.

A rigorous assessment process designed to identify potential and actual influences on the progress and effectiveness of implementation efforts (Stetler et al., 2006).

A framework that allows for evaluation at the end of an implementation.

A process of evaluating a program’s or intervention’s impact or efficacy through careful examination of program design and management (Frey, 2018).

The interrelated conditions in which something exists or occurs (Merriam-Webster, 2022).

The scientific study of methods to promote the systematic uptake of research findings and other evidence-based practices into routine practice, and, hence, to improve the quality and effectiveness of health services and care (Eccles & Mittman, 2006).

Graphs of data over time and one of the most important tools for assessing the effectiveness of change (Institute for Healthcare Improvement, 2017).

A tool for analyzing process dispersion (American Society for Quality, 2022a). It is also referred to as the “Ishikawa diagram" and "cause and effect diagram". The diagram illustrates the main causes and subcauses leading to an effect (symptom).

A four-step process for quality improvement (American Society for Quality, 2022a). In the first step (Plan), a way to effect improvement is developed. In the second step (Do), the plan is carried out. In the third step (Study), a study takes place between what was predicted and what was observed in the previous step. In the last step (Act), action should be taken to correct or improve the process.

The knowledge and skills required to ask and answer a range of questions by analyzing data including developing an analytical plan, selecting and using appropriate statistical techniques and tools, and interpreting, evaluating, and comparing results with other findings (Statistics Canada, 2020).

A method that provides organizations tools to improve the capability of their business processes (American Society for Quality, 2022b). This increase in performance and decrease in process variation helps lead to defect reduction and improvement in profits, employee morale, and quality of products or services.

A scan that combines a series of X-ray images taken from different angles around your body and that uses computer processing to create cross-sectional images (slices) of the bones, blood vessels, and soft tissues inside your body (Mayo Clinic, n.d.).

An approach that considers what works for whom, in what circumstances, in what respects, and how (Pawson & Tilley, 2004).

A formal process in which health care providers work together with patients, families, and care providers to ensure accurate and comprehensive medication information is communicated consistently across transitions of care (Institute for Safe Medication Practices Canada, n.d.). It requires a systematic and comprehensive review of all the medications a patient is taking to ensure that medications being added, changed, or discontinued are carefully evaluated. It is a component of medication management and will inform and enable prescribers to make the most appropriate prescribing decisions for the patient.