Section 1: Introduction and History of Knowledge Translation/Mobilization

Dr. Karen A. Patte; Jayne Morrish; and Megan Magier

Section Overview

In this section, you will be introduced to the what, who, and why of KTE/KMb. You will learn about the concept and goals, who is involved, why KTE/KMb is important, and how it has evolved over time.

Section Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Define KTE/KMb and identify the key characteristics;

- Identify who is involved in KTE/KMb;

- Describe the goals and importance of KTE/KMb; and

- Outline the history of KTE/KMb and how the field has evolved.

Test Your Knowledge

Complete the following activity to assess how much you already know about the content that will be covered in this section.

The Many Terms for KTE/KMb

Knowledge Translation and Exchange (KTE) and Knowledge Mobilization (KMb) are umbrella terms that refer to the many activities that contribute to the relational, iterative, and context-sensitive process of moving of knowledge to action, including the synthesis, dissemination, exchange, and application of knowledge. Numerous terms are often used interchangeably to refer to the concept as a whole or to specific components of the process, such as knowledge dissemination, knowledge translation, knowledge transfer, knowledge exchange, and research utilization. Over 100 different terms were used to describe KMb in health literature in 2006 alone (McKibbon et al., 2010). The varied terminology and definitions partly reflect the emergence of the field from varied roots and the evolution of practices over time, with the choice of term sometimes dependent on the discipline. Research utilization was long used in nursing, while KMb is generally used in social sciences and humanities fields, and Knowledge Translation (KT or KTE) are common in health research. In this chapter, we will use the umbrella terms KTE/KMb.

The Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (2019) uses the term KMb and specifies co-creation or co-production of knowledge in the definition:

An umbrella term encompassing a wide range of activities related to the production and use of research results, including knowledge synthesis, dissemination, transfer, exchange, and co-creation or co-production by researchers and knowledge users. (para. 4)

KT or KTE are commonplace terms today in health and medical fields. First coined in 2007 by Graham et al., KT gained prominence when adopted by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), Canada’s national funding agency for health research. CIHR (2012) defines KT as:

A dynamic and iterative process that includes synthesis, dissemination, exchange, and ethically sound application of knowledge to improve the health of Canadians, provide more effective health services and products, and strengthen the health care system. (p. 1)

Similarly, adapting CIHR’s definition, the World Health Organization (2005) defines KT as:

The synthesis, exchange, and application of knowledge by relevant stakeholders to accelerate the benefits of global and local innovation in strengthening health systems and improving people’s health. (p. 2)

These definitions share a multifaceted conceptualization of KTE/KMb, including activities spanning the synthesis of knowledge to its application. KT has evolved to KTE over time, in order to recognize the importance of exchange within the process and emphasize that rather than a unidirectional process, effective KTE/KMb involves a bi-directional flow of information, rather than a unidirectional process (Graham et al., 2006). Knowledge exchange is a collaboration involving regular sharing of information, ideas, and experience between those who generate knowledge and those who might put the knowledge to use (Reardon et al., 2006).

Knowledge dissemination is considered to be an active “make it happen” process to communicate knowledge by targeting, tailoring, and packaging the message for a particular target audience. Traditionally, dissemination was primarily used to refer to sharing research with academic audiences through peer-reviewed research journals and scholarly conferences, but it is now understood to include any activity that enables the use of knowledge by making it accessible, understandable, and useful to individuals, groups, and organizations. Knowledge dissemination differs from the diffusion of knowledge – a passive and unplanned “just let it happen” process, in which the potential user of knowledge needs to seek it out – which was more often used in early KTE/KMb approaches.

Overlap between KTE/KMb and related fields has also caused confusion. Translational research is the transition from basic laboratory research (e.g., animal and basic research to identify disease mechanisms), to applications to human health and clinical settings (e.g., human clinical and efficacy studies), and finally, to evidence-based practice guidelines (e.g., effectiveness, dissemination, and implementation research) (Zoellner et al., 2015). As outlined in Chapter 3: Implementing Change – Easier Said Than Done, implementation science is “the scientific study of methods to promote the systematic uptake of research findings and other evidence-based practices into routine practice, and, hence, to improve the quality and effectiveness of health services and care” (Eccles & Mittman, 2006, p. 1). As opposed to the practice of implementing evidence, the objective of implementation science is to discover the processes, barriers, facilitators, and strategies to improve implementation, and to develop, test, and refine implementation theories and methods (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2016).

Regardless of the term used, KTE/KMb is a proactive process to ensure the right information is available to the right people, at the right time, and in the right format. Definitions emphasize that the goal goes beyond simply sharing or transferring knowledge, to its implementation and impact on health care and systems. To do so effectively, relationship building and collaboration are critical. Next we discuss who is involved in this process.

Who is Involved?

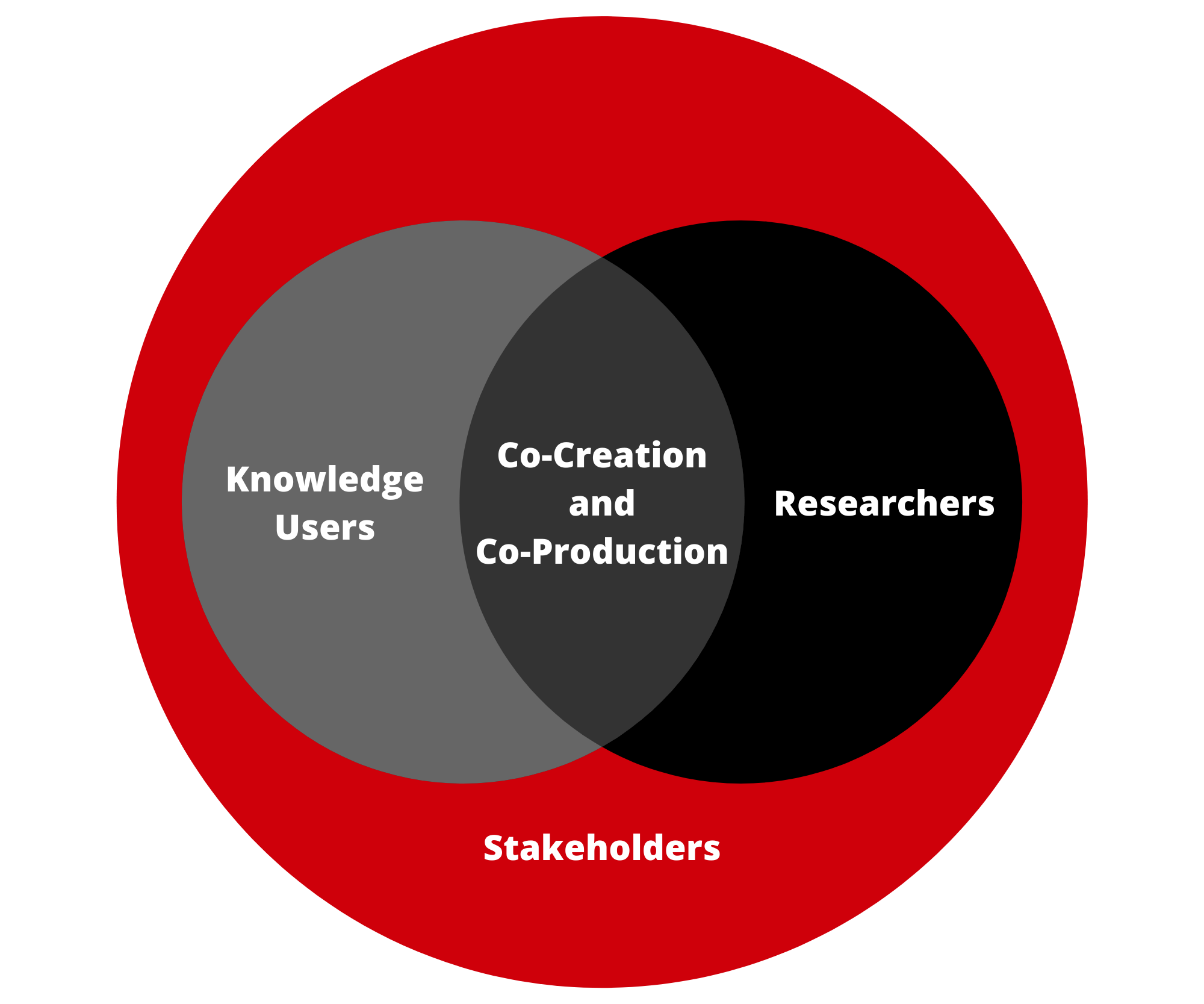

When planning and evaluating KTE/KMb strategies, it is important to ask a priori, which audiences are involved, when, how, and in what context? Similar to the many terms for the process of KTE/KMb or its components, several labels are applied to the different parties concerned, and these too have continued to evolve with the move to more inclusive conceptualizations of knowledge and the “co-production” of knowledge. There are three key groups to consider in KTE/KMb: knowledge creators, users, and stakeholders. KTE/KMb may also employ knowledge brokers.

Knowledge creators or producers are individuals who create new knowledge. Most commonly, knowledge creators are researchers.

Knowledge users or end users are the potential audience of created knowledge. Knowledge users may be people who will receive the care or practice that is based on the knowledge (e.g., patients, the general public) or have the capacity to implement the knowledge (e.g., health decision-makers, practitioners, policy makers). However, knowledge users also hold important knowledge and can actively participate in the process of creating knowledge. Rather than just a reactive audience to already created knowledge, engaging knowledge users throughout the research process helps to ensure the knowledge created is relevant and useful, and therefore, more likely to be applied to practice. Researchers can also be the primary end users of knowledge. Not all research has direct implications for practice, or is ready for external KTE/KMb, but it should be mobilized to other researchers to advance future research in the field, either theoretically, methodologically, or empirically.

Recognizing that knowledge user and creator groups are not mutually exclusive, there has been a move towards terminology such as next users and knowledge holders. Similarly, the terms content experts and context experts have emerged from community engagement literature (Attygalle, 2017). Content experts are individuals with “formal power who have knowledge, tools, and resources to address the issue” (p. 3) – often professionals, service providers, and leaders, whereas context experts have lived experience of the situation or issue at hand, which may include children, youth, and patients (Attygalle, 2017).

There is a continuum of engagement of groups around KTE/KMb, from end users who play a more passive role at the end of a research project, to partners at the most engaged end of the continuum. Research partners agree to participate throughout the research process, as they have specific knowledge to contribute to the creation of knowledge and its dissemination and uptake.

The term stakeholders typically refers to individuals, organizations, or communities in which next users and researchers are situated and that may be indirectly affected by research (Jull et al., 2019). That is, stakeholders may have a direct interest in the knowledge and its use – the process and outcomes of a project – but are not anticipated to directly influence or use the knowledge (Boaz et al., 2018; Jull et al., 2019). Effective KTE/KMb needs to consider the context in which the knowledge is to be applied, which includes the local opinion leaders, given the many political, social, organizational, and environmental influences on change. Tugwell et al. (2006) characterized candidate stakeholders central to the implementation of health science knowledge as the ‘‘6Ps”, including patients, public (community), press, physicians, policy, and the private sector. Larkin et al. (2007) later proposed “8Ps”, adding public health and third-party payers as important parties for successful KTE/KMb.

Knowledge brokers are the middle people or intermediaries who facilitate interactions between knowledge creators and next users – or researchers and decision makers. A knowledge broker works to understand the culture, goals, and needs of knowledge users, and identifies, synthesizes, interprets, and translates research evidence into context appropriate recommendations for them (Dobbins et al., 2009).

Why Do We Mobilize?

When evidence is mobilized to other researchers, KTE/KMb may serve to inform and advance research agendas, theory, and/or methods. Funding agencies now require clear and detailed KTE/KMb plans to ensure timely research uptake, to demonstrate impact, and to justify expenditures. Beyond academic audiences, mobilizing evidence can draw awareness to issues, prompt changes in perspectives or behaviour, and inform policies, processes, and practice. In the case of health, this impact may be defined as informing health care and policy, and ultimately, improving health outcomes.

Attempts have been made to categorize the purposes or types of knowledge use, including instrumental or knowledge-driven use, political or symbolic use, tactical use, and conceptual use (Davies et al., 2015). In a review of KTE/KMb models, Ward (2017) developed 5 outcomes of mobilizing knowledge:

- To develop local solutions to practice-based problems;

- To develop new policies, programs, and/or recommendations;

- To adopt or implement clearly defined practices and policies;

- To change practices and behaviours; and

- To produce useful research or scientific knowledge.

Health research is often conducted under the assumption that it will advance knowledge and eventually translate into improved policies, practices, resources, or programs, and in turn, health. However, despite a strong emphasis on evidence-based practice – in which practitioners make practice decisions based on the integration of research evidence with clinical expertise and the patient’s unique values and circumstances in health care fields (Straus et al., 2005) – the transfer of research evidence to practice continues to be “slow and haphazard” (Graham et al., 2006). As outlined in Chapter 3: Implementing Change – Easier Said Than Done, it is estimated to take approximately 17 years for evidence to be fully adopted in practice (Morris et al., 2011). The failure or lag in evidence uptake means many patients are denied the best possible care (Graham et al., 2006), and the persistent use of outdated approaches represents missed opportunity, potential harm, and wasted human and financial resources (Powell et al., 2017).

Recognition of this “knowledge to action” or “know-do” gap has led to a growing emphasis on KTE/KMb. In a bulletin of the World Health Organization, Pablos-Mendez et al. (2005) state:

Research, we believe, has to be a component of a strategic process rather than an end in itself. Ill-health and premature deaths from preventable causes persist… in spite of available cost-effective interventions in part because there is a gap between what is known and what gets done in practice, i.e., the ‘know-do’ gap. This gap between available evidence and its application in policy and practice is not new, but strategic approaches to address it are urgently needed. To bridge the know-do gap, knowledge must be leveraged effectively to achieve better health. The generation and sharing of knowledge are necessary steps in its effective application. (para. 1)

Knowledge must be heard and understood by people in a position to bring about change, but the process of KTE/KMb must also consider the complex systems and contexts in which decisions are made, with political, organizational, economic, and social influences.

The sheer amount and rapid production of evidence now further complicates implementation and necessitates effective KMb. The challenges and importance of KTE/KMb have become even more apparent in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, which has been referred to by some as a crisis of misinformation following a larger trend of “truth decay” (Kavanagh & Rich, 2018). The Pan American Health Organization (2020) has warned about an “infodemic”, defined as “an overabundance of information – some accurate and some not – that makes it hard for people to find trustworthy sources and reliable guidance when they need it” (p.2).

Deeper Dive

To take a deeper dive on what KTE/KMb is and how it functions within the research process, use these resources:

- Lavis, J., Robertson, D., Woodside, J., McLeod, C., & Abelson, J. (2003a). How can research organizations more effectively transfer research knowledge to decision makers? Millbank Quarterly, 81(2), 221-248. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/pmc2690219/

- Lavis, J. (2003, March 13). How can research organizations more effectively transfer research knowledge to decision makers? [Presentation]. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/50c5/429ce338c7a9f2e69d080f1cfdaf96ab74b4.pdf

- Reardon, R., Lavis, J., & Gibson, J. (2006). From research to practice: A knowledge transfer planning guide. http://www.iwh.on.ca/from-research-to-practice.

- Graham, I. D., Logan, J., Harrison, M. B., Straus, S. E., Tetroe, J., Caswell, W., & Robinson, N. (2006). Lost in knowledge translation: Time for a map?. Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions, 26(1), 13-24.

- Canadian Institutes of Health Research. (2015). A guide to researcher and knowledge-user collaboration in health research. https://cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/44954.html

- Canadian Institutes of Health Research. (2012). Guide to knowledge translation planning at CIHR: Integrated and end-of-grant approaches. https://cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/documents/kt_lm_ktplan-en.pdf

- The University of British Columbia. (n.d.) IKT guiding principles. https://ikt.ok.ubc.ca

- Boland, L., Kothari, A., McCutcheon, C., & Graham, I. D. (2020). Building an integrated knowledge translation (IKT) evidence base: Colloquium proceedings and research direction. Health Research Policy and Systems, 18(1), 1-7.

- Bowen, S., & Graham, I. D. (2013). Integrated knowledge translation. In S.E. Straus, J. Tetroe, & I.D. Graham (Eds.), Knowledge translation in health care.

History of KTE/KMb

From Passive Diffusion to “Science Push” Strategies in the Era of Evidence-Based Medicine

As we can see from the above sections, there is clearly a need for equitable and authentic KTE/KMb. You might wonder how this field emerged in the first place. Looking to history, we can see that after the second World War, in “the golden era of modern research”, the publication of research in scholarly journals and reports was considered sufficient and followed by passive diffusion (Landry et al., 2006). The movement of knowledge-to-action was approached as linear, fixed, and transferable (i.e., one directional and one-size fits all, irrespective of context and next users), with change occurring at the end of the research process.

The 1980s saw the birth of evidence-based medicine, which served as the basis for other evidence-based movements. Researchers and medical professionals aimed to improve clinical decision-making by promoting the use of the latest scientific knowledge, as opposed to practice based on the status quo, individual habits, or pharmaceutical marketing efforts. Gordon Guyatt, a professor of medicine and clinical epidemiology from McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada, first coined the term "evidence-based medicine" in 1990 (Guyatt, 1991). Sackett et al.’s (1996) definition of evidence-based medicine is one of the most frequently cited: “the conscientious, explicit, and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients” (p. 71).

The failure to effectively disseminate evidence was believed to account for the “know-do gap”, and as such, active “push” dissemination approaches emerged to ensure evidence made it into knowledge users’ hands. KTE/KMb strategies remained primarily unidirectional, from researchers to practitioners, and included the preparation and dissemination of systematic reviews, practice guidelines, and research reports, along with educational workshops to assist with interpretation (Landry et al., 2006). In the 1990s, a global network of researchers and health professionals established the Cochrane Collaboration, producing systematic reviews and databases on specific medical issues with the goal to inform health care decisions.

The legacy is that academic researchers are primarily trained and rewarded for scholarly books, peer-reviewed journal articles, and conference presentations, for which the intended audience is typically other scholars. While this system involving rigorous peer-review has important strengths in ensuring the research disseminated is of high standard, it has also contributed to the division between academic researchers and practitioners (Gaetz, 2014). In what has been called a “trickle down” view of the knowledge chain, the researcher’s role was seen as creating and testing knowledge, with dissemination and implementation largely handled by someone else (Van de Ven & Johnson, 2006). While potentially sufficient for basic science, this model has limitations for more applied health research that has direct implications for health policy and practice. For example, many barriers in access exist for non-academic audiences, including the use of technical language, required knowledge to interpret research, and paywalls and copyright restrictions. Also, the one-way flow of information impedes implementation, as the research may not be readily applicable to practice, whether failing to account for the ‘real-world’ context and many barriers to change, or not fitting the next users’ priorities.

The Emergence of the KTE/KMb Field

Despite initial success of evidence-based medicine, the knowledge-to-action gap persisted into the 1990s and today (Graham et al., 2006). An extensive evidence base had developed but it was not being implemented into new or improved health policies, products, services or outcomes (Landry et al., 2006). Further, the knowledge-to-action problem was now conceived as more complex and beginning upstream, in which research was not meeting the needs of knowledge users. That is, the failure to bridge the knowledge-to-action gap is argued to not be a knowledge transfer problem but a failure of knowledge production (Bowen & Graham, 2013; Van de Ven & Johnson, 2006). The research was not addressing questions seen as relevant or of interest to end users, thwarting its use and application (Gaetz, 2014).

In addition to the research-to-practice gap, a practice-to-research gap exists in the mobilization of evidence gained from practice to inform more relevant research. Knowledge is often conceived exclusively as research evidence (Van de Ven & Johnson, 2006). However, beyond promoting the relevance and likelihood of uptake, practice-based knowledge also advances research, providing valuable lessons to promote innovative theories and models to be tested in a discipline (Smith & Wilkins, 2018; Van de Ven & Johnson, 2006).

The former Canadian Health Services Research Foundation (CHSRF) was established in 1996 “to support evidence-informed decision-making, management and delivery of health services through funding research, capacity building and knowledge transfer,” which promoted awareness of the concept of “linkage and exchange” among policy/decision-makers into the early 2000s (Nguyen et al., 2020, p. 2). The CHSRF had set the scene for the CIHR’s initial mandate to advance both the creation of new knowledge and the translation of this knowledge from research into “real-world applications”. Meanwhile, the CHSRF drafted new strategic priorities by 2009 to focus on the identification, spread, and scale of proven health care innovations, in response to the ongoing failure to transfer and apply research findings by scaling up approaches that have already been shown to work, and instead funding new research in what they referred to as “a country of perpetual pilot projects.”

Over the past two decades, there has been a rapid growth in the KTE/KMb literature, including a plethora of definitions, models, and frameworks (Powell et al., 2017). The growth of KTE/KMb has expanded and changed the traditional roles of researchers, moving from an ‘independent’ and detached scientist to becoming an ‘interdependent’, other-focused collaborator and communicator (Gaetz, 2014).

Several shifts are said to have occurred from the era of evidence-based medicine to the KTE/KMb movement. First, the complexity of KTE/KMb as a relational and iterative process was recognized, as opposed to a linear, rational, and one-size fits all event. Second, with increased recognition that evidence is often bound to context and not universal, context-sensitive knowledge grew to be preferred over context-stripped evidence (Reimer-Kirkham et al., 2009). Third, researchers in universities and knowledge users in public or private sector institutions became less siloed with university and community or clinical partnerships. Lastly, there is a move toward more inclusive views of knowledge, with the growing recognition of the diverse ways of generating knowledge beyond formal research. According to Reimer-Kirkham et al. (2009):

From a postcolonial feminist perspective, these concerns extend to name narrow interpretations of evidence that marginalize certain types of knowledge. By relying primarily on knowledge generated through randomized controlled trials that typically do not involve non-English speaking patients, do not account for the social context of people’s lives, and historically have not included representation from women, incomplete non-representative knowledge is applied. (p. 160)

KTE/KMb Timeline

The Current Context of KTE/KMb

Recent literature increasingly recognizes KTE/KMb as “relational and political”, with knowledge “value-laden”; change is complicated by the scope, scale, and number of actors involved, and a range of political, contextual, personal, interpersonal, and organizational influences (Bate et al., 2012; Powell et al., 2017). Acontextual KTE/KMb and reductionists’ views of health and illness are critiqued as not considering the “messiness of everyday” practice, the “complicated power relations shaping any exchange” and the social conditions that determine health (Gaetz, 2014; Powell et al., 2017). To impact change, research evidence needs to be integrated with “informal” knowledge, such as the experiences of health professionals, patients, and carers (Bowen & Graham, 2013; Powell et al., 2017). Thus, effective KTE/KMb must also be “relational and contextually sensitive” (Powell et al., 2017). Further, it must take into account inequities in access to information, the ability to evaluate its quality, and the capacity to apply evidence. KMb/KTE often favours audiences already “information privileged” and fails harder to reach audiences. As explained by Gaetz (2014):

Effective approaches to KMb must not only reimagine how research content is produced and distributed but also address barriers that users face in accessing and utilizing research knowledge, including lack of time, resources, skills, organizational support, and perception that research is not valuable, timely, or relevant. (para. 12)

Newer models of KTE/KMb emphasize the value of going further than simple engagement of next users to developing true and authentic partnerships at an early stage and collaborating throughout the research process (Smith & Wilkins, 2018). Community-engaged collaborative research has long been used in social sciences, unlike the medical sciences where practical applications have historically been developed based on researcher-created evidence (Gaetz, 2014). While less relevant for basic sciences, for health care, policy, and practice research, partnership approaches are said to enhance the relevance, uptake, and impact of research (Oborn et al., 2013; Skipper & Pepler, 2021).

More recently, the integrated knowledge translation (iKT) approach was developed in medical and health fields, in recognition of the values of collaborative research and with more similarities than differences to existing models, such as Engaged Scholarship, Co-Production or Co-Creation, and Participatory Action Research (Nguyen et al., 2020). iKT is defined by ongoing and authentic partnerships where researchers and knowledge users are equal partners in a mutually beneficial research project. The collaboration occurs from start to end, including priority setting and identifying problems, refining research questions, deciding on design and methods, collecting data, analysis and interpretation of results, and dissemination of findings.

Lavis and colleagues (2003a) make note of the knowledge exchange model, which posits that KTE/KMb requires mutually beneficial relationships to be built, developed and maintained across a project between knowledge creators and knowledge users. They explain that “over long periods of time, two-way ‘exchange’ processes that give equal importance to what researchers can learn from decision makers and what decision makers can learn from researchers can produce cultural shifts” (p. 227).

Likewise, Bowen and Graham (2013) describe the broad history behind KTE/KMb and, discussing the strengths and limitations of various approaches to KTE/KMb work, note that “there is increasing evidence that simply disseminating knowledge to potential users of that knowledge after the research has been completed is likely to be of limited effectiveness even if multiple and creative methods are used” (p. 5). The authors further state that “this evolution, from transfer to engagement, in KT theory and practice is occurring alongside, and in response to, other challenges to traditional research approaches, and reflects increasing societal expectations that knowledge must not only be scientifically valid, but also socially robust” (p. 5).

Goodman and colleagues (2017) comment that from a public health and community engaged research perspective “engaging community members in the research process is often the missing link to improving the quality and outcomes of health promotion activities, disease prevention initiatives, and research studies” (p.18).

Applying various collaborative models, knowledge is co-created with and not on or for individuals, groups, or organizations. These approaches necessitate positive and trusting relationships, based on principles of respect, co-learning, openness, support, reciprocity, and shared decision-making (Bradbury-Huang et al., 2010; Nguyen et al., 2020; Skipper & Pepler, 2021). Both researchers and knowledge users are considered experts bringing complementary skills and knowledge to the team. Ideally, some of the typical barriers between researchers and users are broken down, and they learn from each other. Researchers bring research methodological skills and content expertise, while next users bring expertise related to the research topic and context and are well-positioned to move results into practice. Ultimately, their diverse perspectives can foster a more complex understanding of issues, the challenges and opportunities for change, and innovative solutions. However, despite recognition of the values of collaboration, the difficulties initiating and sustaining such work (e.g., in terms of issues and politics around sharing power, resources, and credit) prevent widespread engagement (Lozano et al., 2012; Plamondon & Pemberton, 2019). You will learn more about knowledge exchange in terms of selecting KTE/KMb strategies in Section 3: Knowledge Translation/Mobilization Strategies.

Deeper Dive

Community engagement and equitable knowledge exchange are complex and involve long-term relationship building and collaboration (Goodman et al., 2017). Understanding the principles and complexities of community engagement with the KTE/KMb context goes beyond this chapter, but to take a deeper dive, use these resources:

- Attygalle, L. (2020). Understanding community-led approaches to community change. Tamarack Institute. https://www.tamarackcommunity.ca/library/paper-understanding-community-led-approaches-community-change-lisa-attygalle

- Cazaly, Lynn. (n.d). Levels of participation [Video]. Vimeo. https://vimeo.com/93902630

- Chin, S. (2019). Best practices for community engagement (Doctoral dissertation, University of British Columbia). https://open.library.ubc.ca/soa/cIRcle/collections/graduateresearch/66428/items/1.0386712

- Clinical and Translational Science Awards Consortium Community Engagement Key Function Committee Task Force on the Principles of Community Engagement. (2011). Principles of Community Engagement (2nd ed.). https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/communityengagement/

- Gonzalez, R. (2020). Spectrum of community engagement to ownership. Facilitating Power. https://www.facilitatingpower.com/spectrum_of_community_engagement_to_ownership

- Neufeld, S. D., Chapman, J., Crier, N., Marsh, S., McLeod, J., & Deane, L. A. (2019). Research 101: A process for developing local guidelines for ethical research in heavily researched communities. Harm Reduction Journal, 16(1), 1-11. https://harmreductionjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12954-019-0315-5

- University of South Florida, Office of Community Engagement and Partnerships. (n.d.). Community-engaged scholarship toolkit. https://www.usf.edu/engagement/faculty/community-engaged-scholarship-toolkit.aspx

Summary

KTE/KMb is a multidimensional concept encompassing the many activities that aim to close the knowledge-to-action gap. It is a proactive and iterative process comprising all steps between the creation of new knowledge and its application and impact, including knowledge synthesis, dissemination, exchange, implementation, and sometimes, co-production. To be effective, KTE/KMb must be tailored with an understanding of the audience and context in which the knowledge is to be applied. For this reason, building relationships and ongoing collaboration are central to the process.

Test Your Knowledge

Complete the following activity to assess how much you learned about the content that was covered in this section.

The many activities that contribute to the relational, iterative, and context-sensitive process of moving of knowledge to action, including the synthesis, dissemination, exchange, and application of knowledge.

An active “make it happen” process to communicate knowledge by targeting, tailoring, and packaging the message for a particular target audience.

A dynamic and iterative process that includes synthesis, dissemination, exchange, and ethically sound application of knowledge to improve the health of Canadians, provide more effective health services and products, and strengthen the health care system (Canadian Institutes of Health Research, 2012, p. 1).

The synthesis, exchange, and application of knowledge by relevant stakeholders to accelerate the benefits of global and local innovation in strengthening health systems and improving people’s health (World Health Organization, 2005, p. 2).

A collaboration involving regular sharing of information, ideas, and experience between those who generate knowledge and those who might put the knowledge to use (Reardon et al., 2006).

The potential audience of created knowledge.

Individuals, organizations, or communities in which next users and researchers are situated and that may be indirectly affected by research (Jull et al., 2019).

A passive and unplanned “just let it happen” process, in which the potential user of knowledge needs to seek it out.

The transition from basic laboratory research (e.g., animal and basic research to identify disease mechanisms), to applications to human health and clinical settings (e.g., human clinical and efficacy studies), and finally, to evidence-based practice guidelines (e.g., effectiveness, dissemination, and implementation research) (Zoellner et al., 2015).

The scientific study of methods to promote the systematic uptake of research findings and other evidence-based practices into routine practice, and, hence, to improve the quality and effectiveness of health services and care (Eccles & Mittman, 2006).

The interrelated conditions in which something exists or occurs (Merriam-Webster, 2022).

Individuals who create new knowledge. Most commonly, knowledge creators are researchers.

The middle people or intermediaries who facilitate interactions between knowledge creators and next users - or researchers and decision makers.

Individuals with formal power who have knowledge, tools, and resources to address the issue (Attygalle, 2017, p. 3).

Individuals with lived experience of the situation or issue at hand (Attygalle, 2017).

An overabundance of information – some accurate and some not – that makes it hard for people to find trustworthy sources and reliable guidance when they need it (Pan American Health Organization, 2020, p. 2).

The conscientious, explicit, and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients (Sackett et al., 1996, p. 71).

Ongoing and authentic partnerships where researchers and knowledge users are equal partners in a mutually beneficial research project.