Section 1: Introduction to Data and Data Literacy

Dr. Sinéad McElhone; Sherri Hannell; and Noah James

Section Overview

This section aims to provide a ‘birds-eye view’ to understand how data, throughout its lifecycle, needs to be handled, maintained, stored, cleaned, analyzed, and disseminated properly, and how insights derived from data can be used in evidence-informed decision-making.

In the majority of post-secondary education, there will be discussions about data, statistics, and evidence, but often, what is missed is the “how” these aspects fit within the broader data literacy learning competencies. It is important that learners have a basic understanding of data literacy and how it pertains to their learning to be productive and successful health professionals in the future.

Section Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Define data literacy;

- Understand core data literacy competencies; and

- Identify the core steps in a data literacy plan to support the development of an organizational culture that embraces the use of data to inform decisions.

Test Your Knowledge

Complete the following activity to assess how much you already know about the content that will be covered in this section.

Now try out this Learning Primer to test your knowledge about data literacy! This primer quiz has ten questions and provides you with a score at the end. This is followed by a data learning pathway with resources and ideas on how to enhance your data literacy knowledge. This is a great resource to engage with in order to see where you are at and what you might need to do to enhance your understanding of data literacy.

What is Data?

As we get started, it is important to define a number of terms that you will continually see as you progress through this chapter.

Data is defined as facts and statistics in their raw form, collected for reference, analysis, or decision-making. Data is the foundation of information.

Information is data that is processed, interpreted, organized, structured, and presented to make it meaningful. Information is any documented representation of knowledge, such as facts, data, data assets, records, or decisions in any medium or form. Information is data with relevance and purpose.

What is a Data Asset?

An asset is described as a resource that has value that an organization either owns or is in control of. Like other organizational assets, data has value that can be leveraged. The value that can be derived from data can increase or decrease depending on how effectively it is managed. Data assets increase their value by ensuring that the data contained within them is of high quality, easily accessible, shared when possible, and efficiently managed and governed.

A data asset is defined as a named collection of related data elements that is formally managed as a single unit. They may be a collection of facts represented as text, numbers, graphics, images, sound, or video, and are the raw material from which information can be derived and decisions can be made.

Within organizations, data assets can come from a variety of providers, including internally, and if relevant, from external partners. For example, an external partner can be another group or organization that acts as a data provider, such as Home and Community Care Support Services (HCCSS) providing data to an agency that is conducting data analysis.

Data and data assets are the cornerstones that enable the creation of analytical insights. Data is a strategic asset to any organization, requiring a coordinated approach to management through the development and execution of authorities, accountabilities, and controls to ensure consistent practices that are effective and efficient.

For example, many organizations will have policies and procedures related to the collection, retention, and destruction of data, which must be adhered to, or else they risk being fined by various agencies. According to the Government of Canada Office of the Privacy Commissioner (2014):

Principle 5 of the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA) states that “personal information that is no longer required to fulfill the identified purposes should be destroyed, erased, or made anonymous. Organizations shall develop guidelines and implement procedures to govern the destruction of personal information.” (para. 3)

Please go to Section 5: Health Data Management and Privacy Legislation for more information on this topic.

Data Lifecycle

What is the Data Lifecycle?

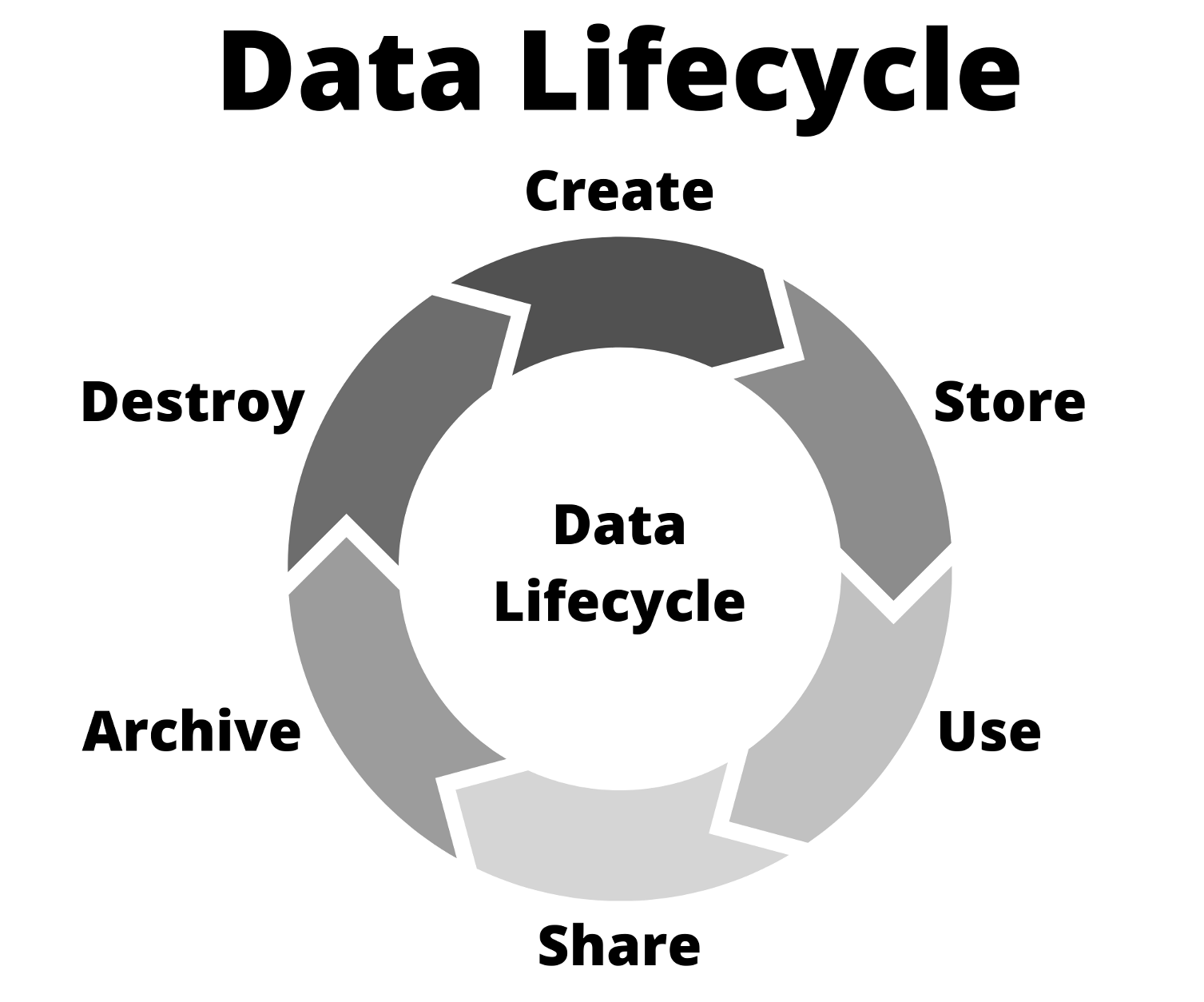

The data lifecycle refers to the sequence of events that data goes through from its initial creation or capture to its eventual archiving or destruction at the end of its usefulness.

Although the steps involved in the data lifecycle can vary slightly depending on the source referenced, there are usually six core stages in the data lifecycle. We will discuss this in greater detail in Section 4: The Data Lifecycle.

The Six Stages of the Data Lifecycle

The six core stages are as follows:

Data Literacy

According to Statistics Canada (2022):

Data literacy is a key skill needed in the 21st century. It is generally described as the ability to derive meaning from data. Data literacy focuses on the competencies or skills involved in working with data, including the ability to read, analyze, interpret, and visualize data, as well as to drive good decision-making. (para. 1)

Many learners will touch upon aspects of data literacy throughout their education, perhaps without even realizing it – some of you may collect data as part of a research project, some of you may undertake statistics on data as part of a course, and some may have the opportunity to work with data visualization tools such as PowerBI. These are all aspects of data literacy.

But data literacy is much larger than this. According to the Data Literacy Project (2015):

Data literacy is the ability to comprehend, create, and communicate data, and is the first level of the tri-level literacy, fluency, mastery scale. Data-literate individuals have the knowledge, understanding, and skills to connect people to data. Data literacy spans both qualitative and quantitative data, and is enabled by a broad range of data-related capabilities and learning outcomes, including but not limited to:

-

- Data collection and grounding in sound methodology; creating data sets with appropriate metadata;

- Data management — how to structure, store, preserve, harmonize, and enable sharing of raw data;

- Data analysis — how to transform raw data into usable information and/or knowledge; incorporates the process of approaching an unfamiliar data set, understanding it, and identifying core features or anomalies; performing appropriate summations, aggregations, highlights, etc.; reaching appropriate conclusions and insights; and achieving relevant results;

- Data visualization, and the honest, ethical, accurate, and compelling graphic representation of data;

- Data policy, regarding privacy, security, retention, organization, openness, integrity, metadata, data models, open data, and sharing;

- Data dissemination and sharing, metadata; how to make data open and interoperable;

- Creation, maintenance, and use of metadata, including measures of data quality; and

- Evidence-based decision-making, and in general the effective and ethical use of data to inform policy-making, decisions, or even personal opinions. (para. 6)

The Importance of Data Literacy

We live in a time where there is so much information and data available, and health data is no exception. It is important that we harness the strength of this data to make great decisions that will enhance the health services we provide.

The sheer volume of data now available from multiple sources such as electronic records (e.g., hospital-based electronic medical records (EMRs)), Ministry based systems such as mass immunization health data, data from internal and external public surveys, data gathered from apps (e.g., weather apps, GPS apps, etc.), website analytics (e.g., social media engagement analytics), data gathered from laboratories (e.g., water testing, biological specimens) in organizations – whether for- or not-for-profit – requires proper management to become useful data.

As previously mentioned, there will be specialists in the organization who will take the lead in areas such as the collection of health data within an electronic health record (EHR) (e.g., health informaticians). Data stewards are tasked with cleaning these data while epidemiologists would then be responsible for the analyses of such data to produce insights. However, the general workforce needs to be aware of their basic responsibilities (e.g., no inappropriate data sharing/storing or retaining data for an appropriate period) and have basic levels of comprehension of how to use data pertinent to their business area to inform decision-making.

QUICK SIDENOTE: Historical Context

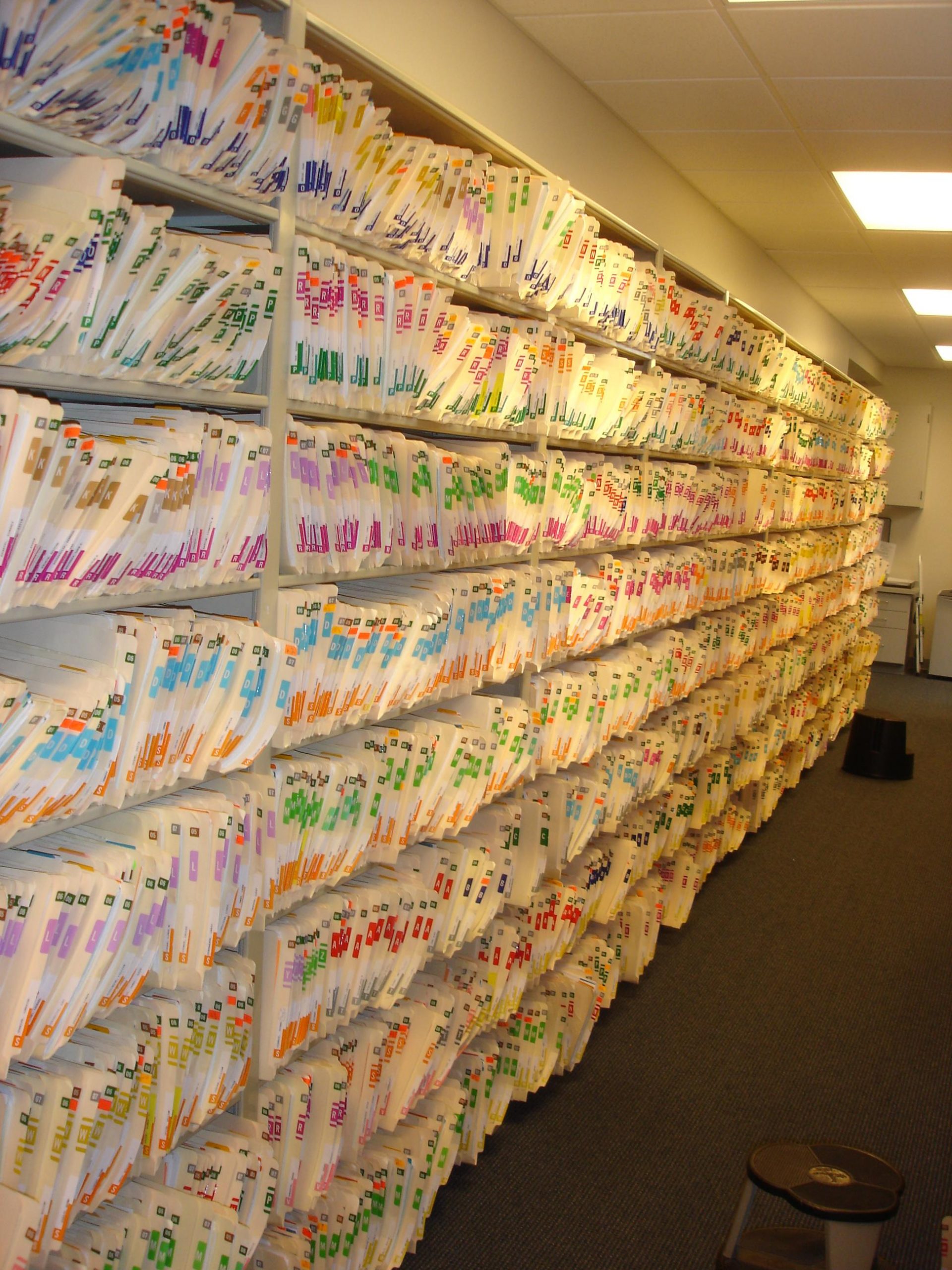

Historically, these types of health data/health records were only available on paper and would be filed, stored, and shredded, as there are very defined processes for dealing with paper.

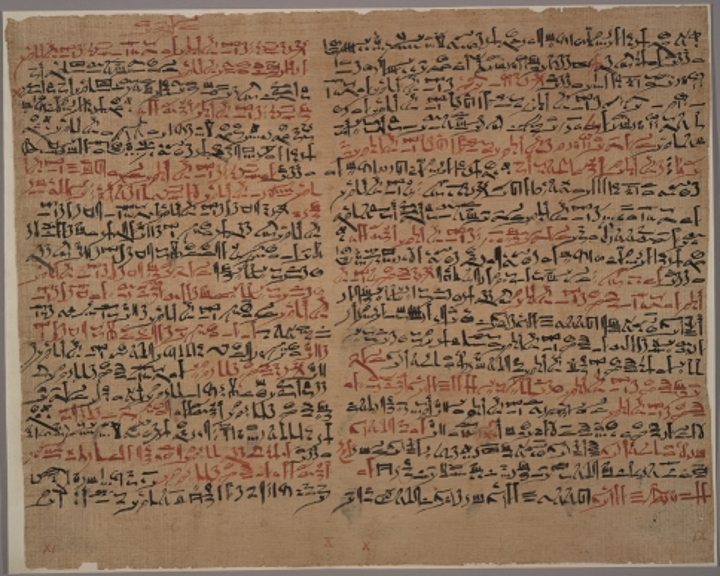

Did you know? Paper health records have been found back as far as Egyptian times (1600 BC). Here is a written document on papyrus describing war wounds:

Imagine trying to analyze the data from all these records on paper? How would you do this? How would you even start? Now think about the retention/storage and destruction of this kind of health information? Many of these types of health data need to be retained for long periods of time in a secure location. There are now many organizations across the world that safely store, retain, dispose, and shred paper records in accordance with various legislation, including medical records.

Now consider the principles and practice from a tangible product (i.e., paper health records) to an intangible product (i.e., health data in a database). In recent decades, there is even more information and data collected electronically by health and health-related organizations. For example, health information can be collected via 1:1 client interaction in a hospital, long-term care home, or mass immunization clinic, and documented within an EMR. Health and health-related information can also be gathered within health surveys by researchers at universities, governments (e.g., Canadian Community Health Survey), or private companies. Aspects of this information are extracted and stored as data for analyses while the remainder stay within the health record. In recent years, many organizations have the capacity to store terabytes of information and data, both on premise and in cloud format, so new strategies and policies need to be adopted to deal with the amount of raw data and information available digitally and how to collect, use, and dispose of this legally, ethically, and securely.

According to eHealth Ontario (n.d.):

An EHR is a secure lifetime record of your health history. It gives your health care team, including family doctor, nurses, emergency room clinicians, and specialists, real-time access to your relevant medical information, so they can provide the best care for you. eHealth Ontario has built the provincial system that gives thousands of health care providers at hospitals, family practices, long-term care homes, pharmacies, and more access to their patients’ EHRs so they can quickly look up lab results, publicly funded dispensed medications, digital images (like x-rays and MRIs), hospital discharge summaries, and more. (para. 1)

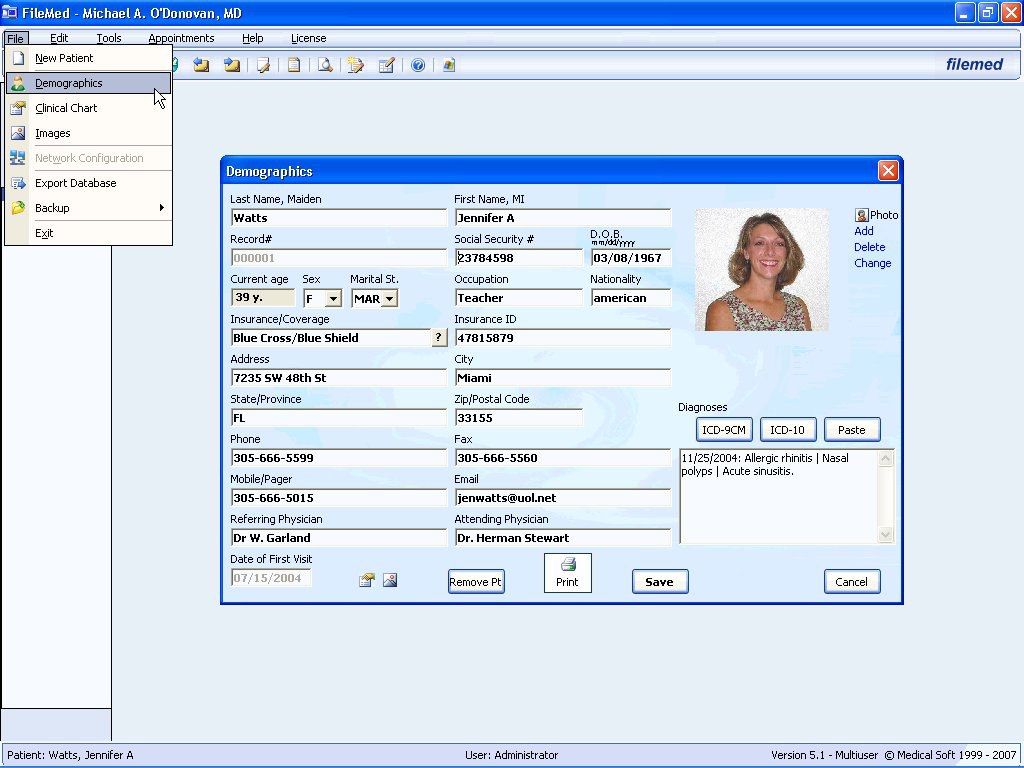

QUICK SIDENOTE: What is the Difference Between an Electronic Medical Record (EMR) and an Electronic Health Record (EHR)?

An EMR is a digital version of a patient’s chart. It contains the patient’s medical and treatment history from one organization. In contrast, an EHR contains the patient’s records from multiple providers/organizations and provides a more holistic, long-term view of a patient’s health. Bonderud (2021) states that “EHRs are multifunctional and used for everything from documentation and medication management to clinical decision support, reporting and analytics, and results management” (para. 10).

Technology can only do so much to integrate data-driven decision-making into everyday practice, unless it is backed by an organizational culture that understands and values it. Without a culture that values and understands the use of technology and data, the consequences can be crippling, leading to poorly informed decision-making, privacy breaches, litigation and penalties, reputational impacts, and loss of customer trust.

Data Literacy and Higher Education

From an institutional perspective, universities gather so much personal and personal health information from their staff and students from medical records, to home and student addresses, to car licence plates, to academic transcripts, so gathering, retaining, and using these data for decision-making is very important. Universities, just like hospitals, public health units, and other agencies, must abide by the various federal and provincial laws set to protect our data. Please go to Section 5: Health Data Management and Privacy Legislation for more information on this topic.

But from a student perspective, how does data literacy apply to you in higher education? A recent article by Testani and Zhou (2022) highlights how important this is from a research perspective:

“Effective data management is increasingly recognized as being critical for quality research,” says David Buckeridge, Professor in the Department of Epidemiology, Biostatistics and Occupational Health; Chief Digital Health Officer, McGill University Health Centre; Scientific Lead, Data Management and Analytics, COVID-19 Immunity Task Force. “A major reason is that ensuring the integrity and security of research data is necessary for reproducible and transparent research. Sound data management practices are also important for continued public trust and maintaining compliance with Canadian and international laws and regulations, as well as policies of funding agencies and publishers.” (para. 2)

The Canadian Tri-Agencies recently released a draft of the Tri-Agency Research Data Management Policy for Consultation, which will require institutions to create an institutional research data management strategy (Government of Canada, 2021). The agencies stated that research data collected through the use of public funds should be responsibly and securely managed, and be, where ethical, legal, and commercial obligations allow, available for reuse by others.

Test Your Knowledge

Complete the following activity to assess how much you learned about the content that was covered in this section.

The ability to understand and communicate data as information (Jackson & Carruthers, 2019).

Facts and statistics in their raw form, collected for reference, analysis, or decision-making.

Data that is processed, interpreted, organized, structured, and presented to make it meaningful.

A named collection of related data elements that is formally managed as a single unit. They may be a collection of facts represented as text, numbers, graphics, images, sound, or video, and are the raw material from which information can be derived and decisions can be made.

The knowledge and skills required to ask and answer a range of questions by analyzing data including developing an analytical plan, selecting and using appropriate statistical techniques and tools, and interpreting, evaluating, and comparing results with other findings (Statistics Canada, 2020).

The sequence of events that data goes through from its initial creation or capture to its eventual archiving or destruction at the end of its usefulness.

The knowledge and skills required to create meaningful tables, charts and graphics to visually present data (Statistics Canada, 2020). This also includes evaluating the effectiveness of the visual representation (i.e., using the right chart) while ensuring accuracy to avoid misrepresentation.

This is data about data, including the definitions and descriptions about the data, and makes finding and working with data easier.

The business function of planning for, controlling, and delivering data (Fircan, 2021b).

The knowledge and skills to assess data sources to ensure they meet the needs of the gatherer or organization (Statistics Canada, 2020). This includes both identifying errors and taking action to address the issues with the data.

The knowledge and skills required to use data to help in the decision-making and policy-making process (Statistics Canada, 2020). This includes thinking critically when working with data, formulating appropriate business questions, identifying appropriate datasets, deciding on measurement priorities, prioritizing information garnered from data, converting data into actionable information, and weighing the merit and impact of possible solutions and decisions.

A pattern of shared basic assumptions learned by a group as it solved its problems of external adaptation and internal integration, which has worked well enough to be considered valid and therefore, to be taught to new members as the correct way to perceive, think and feel in relation to those problems (Schein, 2010).