Module 2: Life Records

Lesson 2.1: Reading Censuses: Everyday life in Acadie

Introduction

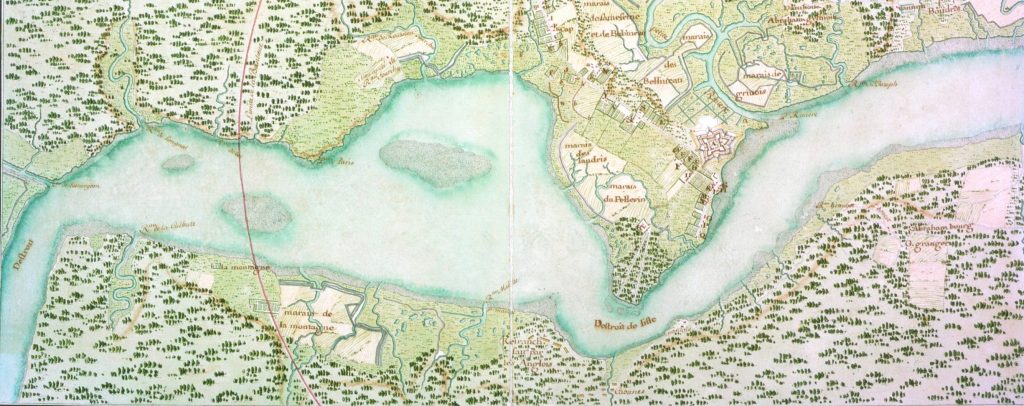

Settlers began arriving in Mi’kma’ki from France after 1632. For the most part, these people settled at Tewopskik, the Mi’kmaw name for the river presently known as Annapolis. The French called this place Port Royal and they labelled the river the Dauphin. As the population expanded, colonists built small settlements along the river rather than living more centrally around France’s fortifications. At its furthest extent, Acadian farms stretched for about 30 kilometres up river.

Rather than transforming forests into fields, the Acadians instead built earthen walls around the river’s extensive salt marshes. These walls – known as dykes – held back the tidal waters, which rise about 15 ft to 18 ft at this location. Once enclosed and drained, the marshes could dry out, desalinate, and then be used for growing crops.

In the settlement’s early days the population was small and grew slowly. By the early 1670s, the population had risen to about 350 people – around 67 families. It did not take long, however, for the population to outgrow their settlements. Within the decade, Acadian families expanded to other locations around the Bay of Fundy. Like Tewopskik, the places where the Acadians settled tended to have very high tides and large expanses of tidal salt marshes. By the 1680s, Acadians had built new homes along Jijikwtuk, Setnuk, Knektkuk, Maqmekwitk, Amaqapskiket, We’kopekitk, and Siknikt. These were Mi’kmaw places, that the Acadians renamed Minas, Pisiquid, Cobequid, and Beaubassin, along with several other smaller locations.

Concerned about the growing population and continued political turmoil, France increasingly sought to understand who was living in their isolated colony. The first census of the Acadian population was taken in 1671, after French administrators returned to the region following sixteen years of supposed English rule. From that point forward, censuses were taken of the French population in 1679, 1687, 1693, 1695, 1698, 1701, 1703, 1707, 1714, 1720, 1728, 1731, 1733, 1735, 1737, 1739, 1749, and 1752.

Censuses in the 17th and 18th centuries were not like they are today. Sometimes censuses provided only basic information about a community, such as the total number of residents, while at other times they collected considerably more information about the community itself. These more detailed censuses are good sources for important information about everyday life in Acadie. They must, however, be used cautiously.

There are three questions you must bear in mind when using this type of primary source:

- How reliable is the census? Today, censuses are collected following a rigorous methodology and set of procedures. This was not the case in the 17th and 18th centuries. In fact, it is clear that census protocols and results varied wildly during this period. At Port Royal, for example, censuses were taken in both 1700 and in 1701. Despite being taken only one year apart, there are significant differences between them. Their composition varies in both the names of the people enumerated and personal details, such as their ages or family structure. The reason for these discrepancies is unclear. We know, however, that some Acadians resisted being enumerated, and their disdain likely accounts for some of these problems.

- What assumptions determined the type of information recorded in the census? Different census takers organized their information differently. Some people chose to organize their censuses by household or residence, others were interested in nuclear families, while still others were just interested in men who could bear arms. Each style of organizing the census provides unique opportunities for understanding both the people being enumerated as well as the motivations of the census taker. This can, however, make comparing censuses challenging and sometimes impossible.

- What type of information mattered to census takers? Cultural factors also determined the type of information that census takers recorded. In Catholic communities, for example, it was common for census takers to be much more precise with the ages of younger members of the population than they were with older members. This is because the age at which someone was married was important in the Catholic church, but after marriage their ages were less important for record keeping purposes. As you will notice in Antoine Gaulin’s 1708 census, it was somewhat common for an older person’s age to be rounded to the fives or tens once they surpassed the typical age for marriage.

Despite these challenges, censuses can be incredibly useful tools for learning about and understanding a population. In the three activities in this unit, we introduce you to three different styles of census and some basic tenets of historical demography. As you work through each activity, create a single document that compares each census with the others. What does the structure of each census tell us about the purpose for which it was created?

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this lesson, you should be able to:

- Recognize patterns of everyday life in late 17th– and early 18th-century Acadie.

- Analyze census data to better understand and compare the worlds in which the Acadians and Mi’kmaq lived.

- Develop in-depth knowledge about three specific communities in Acadie.

Technologies used in this lesson

MS Excel

- Excel is one of the most common spreadsheet tools available. By using spreadsheets, we can organize information in ways that helps us better understand its meaning. We have built this activity using MS Excel but you can also use Google Sheets or another spreadsheet software, if you prefer.

- Download the digital spreadsheets, which you can find below in the documents section.

ArcGIS

- ArcGIS is a digital mapping tool that you have already explored in the story map in Lesson 1.1. In the second exercise in Activity 3 in this lesson, you will extend your learning by using the “sketch” function to make a basic map. To complete this activity, you will need to create a public account on ArcGIS’s online platform. We have also created a tutorial worksheet for you, which will help you begin to use ArcGIS.

Instructions

Documents

-

- Recensement General du Pays de la Cadie, 1685-1686, Dalhousie University Archives, MS-6–13.

- We know very little about Joseph de Gargas, the Écrivain du Roi in Acadie during the mid-1680s, aside from the census he took in 1687.

- An original copy of the Gargas census is held in the Dalhousie University archives and is available online, and a published transcribed copy can be found in “General Census of the Country of Acadie, 1687–1688,” in William Inglis Morse, ed., Acadiensia Nova, Vol. 1, (London: Quaritch, 1935), pp. 144–55.

- Download the transcribed material needed for this lesson:

-

Recensement Général fait au mois de Novembre mille sept cent huit de Tous les Sauvages de l’Acadie, 1708, Edward E. Ayer Digital Collection, MSS 4, 751.

- Antoine Gaulin was born in 1674 on Ile d’Orleans, an island located just downriver from the town of Quebec. He studied at the Quebec seminary and was ordained a priest in the Séminaire des Missions Étrangères in 1697. The following year, he moved to Pentagouet and in 1702 was appointed Vicar-General for the Acadian colony. As warfare between France and England brewed in the early eighteenth century, Gaulin became more involved with supporting France militarily, which was one of the reasons this census was taken in 1708.

- An original copy of the Gaulin census is held in the Newberry Library. This transcription is from the Bibliotheque et Archives Nationales du Quebec.

- Download the Age Pyramid example created from this document:

-

- Much like with Gargas, the biography of the Sieur de la Roque is relatively incomplete and we know little about him. We know from a letter about his work that la Roque was the son of one of the king’s musketeers and served France during the War of Austrian Succession, but the rest of his biography remains opaque.

- The original of this census can be found in the New France Archive while a transcription of this census can be found in the Public Archives of Canada’s annual report in 1905. Using the Internet Archives’ Optical Character Recognition, we have cleaned up the census to make it easier for you to use. This file is compatible with hypothes.is.

- Recensement General du Pays de la Cadie, 1685-1686, Dalhousie University Archives, MS-6–13.