6 Chapter 6: Navigating Difficult Conversations: Strategies for Equitable and Inclusive Engagement

Jacob DesRochers

Queen’s University

Setting the Context

My first difficult conversation in higher education occurred in a sexual violence prevention seminar. I was a new facilitator, and wildly unprepared for the high degree of misinformation that would be brought into the space by new students during” Frosh Week.” I quickly learned that I needed to equip myself with tools for “calling students in” versus “calling students out” when dispelling myths about survivorship. I arrived to sexual violence prevention work as a survivor of on-campus violence. However, my relationship to this work has been the foundation for larger questions about equity, diversity, inclusivity, and Indigeneity in higher education.

With the shift to remote teaching and learning, I began having larger conversations about navigating difficult conversations in remote learning and teacher education. I have developed resources for the Faculty of Arts and Science at Queen’s University that engage the topic; I have facilitated workshops in the Faculty of Education (where I presently work and learn), and the Centre for Teaching and Learning; and I have been an invited lecturer to Dominican University of California, where I’ve engaged both in-service and pre-service educators in self-reflexive exercises to help evaluate when a conversation may be difficult on the basis of identity, relationships, and our social positions.

This chapter offers strategies and perspectives that have been effective in my own teaching and learning. Having said that, I share these approaches not as “best practices” or “promising practices,” but rather considerations that may be useful in helping us develop our own approaches to difficult conversations and our own ethics of care.

Scenario

Ezra is a new assistant professor at a small university’s faculty of education in Ontario. Their semester is off to a busy start, as they are teaching three sections of a multi-term course, recently began supervising two new graduate students, and they serve as the faculties’ equity, diversity, and inclusion coordinator at the associate dean’s request. With a mounting workload and tight deadlines, Ezra is also worried about supporting meaningful learning in their remote classroom.

Ezra has just finished delivering a training module on universal design for learning (UDL) to their first section of second-year teacher candidates. They’ve made it a practice to spend 15 minutes reflecting on the course content, the students’ interactions, challenges that emerged during class, and teaching wins (practices they will continue to use in future lessons). Ezra notes that monitoring the classroom chat on Zoom was a challenge; they also observe that some students appeared more confident in sharing opinions that they perhaps would not have expressed in face-to-face instruction. As they begin to revise their lesson plan for their next section of students, they receive an email from a student. The student explains that they felt uncomfortable in their breakout sessions because one of their peers continuously monopolized the group discussion. Further, the student expresses concern about the safety of breakout sessions, as the same peer student shared damaging stereotypes about individuals with intellectual disabilities. As they begin to draft their response to the peer student, they receive a second email – a similar concern, but this time a student has identified that someone has posted a harmful comment in an asynchronous discussion thread intended for students to engage in further discussions after class. Ezra realizes they are struggling to navigate difficult conversations in the remote classroom.

Learning Outcomes

- Explain what makes an interaction or conversation difficult.

- Identify some practices for establishing an equitable learning community.

- Evaluate our own teaching strategies to identify instructional mediums that foster inquiry-based learning and encourage critical thinking.

- Appraise our syllabi for potential difficult conversations and prepare a plan for addressing these topics effectively.

Key Terms: planned discussion, unplanned discussion, misinformation

Self-Talk

Prior to the start of my first semester of teaching, a mentor asked me a seemingly innocuous question: “Why you and not someone else?” Anticipating my desire to respond in the moment, they added, “Sit with this question as you design your syllabus. How will you support your students in a way that another candidate can’t?”

Apart from degree qualifications, I was a unique candidate because of a lengthy history of instructional support and—at the time—I held a contract with the university in which I was advising instructors in developing learning outcomes and materials for remote delivery. My mentor’s question tossed me into an existential crisis. The question was not about being the “better candidate.” Rather, I was being asked to unpack my identities before I began to conceive of my students’ needs. This relationship to instructional design is self-reflexive. I am reminded of a print that hangs above a colleague’s desk: We teach who we are.

When thinking of my syllabus, or helping an instructor design or revise their syllabus, I sit with the list of questions represented in Table 1. Reflecting on our identities and experiences is the first step towards building a learning community where difficult conversations can be had. How we answer questions about our identities is a valuable exercise in evaluating what self-work needs to be done before the dialogue.

Table 1: Reflecting on our identities

| Self-Knowledge | Who are we, and how do our identities and positionalities inform our teaching practices? For example,

|

| Purpose Relationships |

|

Self-Knowledge

Identity work, as a reflexive practice, sets the groundwork for understanding how we will navigate a difficult conversation in our classrooms. For example, when facilitating workshops on sexual violence prevention, I often return to the following question:

Who am I, and how does my identity position inform my teaching practice?

I am a White, queer, cisgender male. I am a survivor. I am a settler.

As a White man, doing sexual violence prevention work within a university, I often think about the ways in which I occupy spaces where anti-violence work takes place. I have learned to sit with the process of White men’s anti-violence ally development – this often consists of a disclosure of my own survivorship, correcting myths about the sexual assault of men and boys, and navigating microaggressions that tend to arise through the discomfort of White men talking about sexual violence prevention as a compulsory workshop during Orientation Week, or as a requirement of Varsity Athletics. As a survivor, I have learned to recognize what topics are sensitive – I may avoid speaking on these topics, relying on didactic slides or other educational tools. As a White settler, I’ve also learned to take ownership of how I may be complicit in an ongoing system of racism and colonialism within the institution that I work. I am candid when I share about my roles and responsibilities, and open to feedback on areas for further learning as a facilitator.

Self-knowledge is developing an ethic of care for the community that we are engaging with. How we recognize our own social locations creates space for us to consider the identities of our students.

Purpose

How do we want to contribute to the people around us? Our abilities to support difficult conversations first begins with understanding either why they need to occur or what institutional conditions serve as an incubator for their potential occurrence. What is the purpose of the dialogue? Further consider, how does our teaching make connections that are context specific, and engage broader realities? Supporting difficult conversations requires using learning materials in which students see themselves. This learning material may celebrate the tacit knowledge that students have, creating space to recognize the learner as an expert.

Are we aware of the voices privileged within our syllabi and instructional materials? We need to seek out learning material that engages a myriad of identities to represent authentic experiences. We need to ask ourselves, “Do I need to speak here?” We can centre voices of other scholars/folks in our teaching, drawing on lived experiences rather than our interpretations of these experiences.

Finally, we need to ask ourselves if we are sensitive to individual students’ readiness to be receptive to sensitive topics? The remote classroom often does not permit the same observation of social dynamics. Affect and potential hostility are masked by blank screens, challenging our ability to evaluate how a topic is being received. We need to take time to build classroom competencies before engaging students in topics that elicit conflicting responses. When building our syllabi or workshops, we might ask ourselves:

- What information may students require before they can engage with the topic?

- If we anticipate gaps in students’ understanding, how can we supplement students’ learning with resources that can be accessed prior to, during, or after their learning?

- Is the information in question, “nice to know” or “need to know”? If it is “nice to know” information, consider offering this information as recommended reading. If it is “need to know” information, consider using learning materials that can build a foundation to more effective dialogue.

Relationships

Difficult conversations do not take place in isolation. After a difficult conversation, it is important for both us and our students to have a space to connect with/or access supports, and to continue learning. Who can we access as dependable supports? Think of colleagues, mentors, friends, a therapist. To the same end, who can our students access to debrief a difficult conversation? Think of student mental health services, interfaith chaplains, Indigenous Elders, and peer support systems.

Table 2: Relationship-building

| Anticipate | Assess | Commit |

| Who will be present in our learning communities? How can we accommodate their needs? What knowledges do they bring with them? | What ideological positions do we possess and how do they hinder our teaching? What spaces do we occupy? How do these positions and spaces impact the ways in which we communicate knowledge? | Check our emotions, biases, and the resources in our tool kits. What can we unpack before we enter our learning communities? |

How Difficult Conversations Emerge

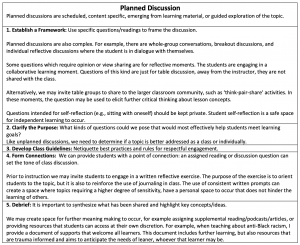

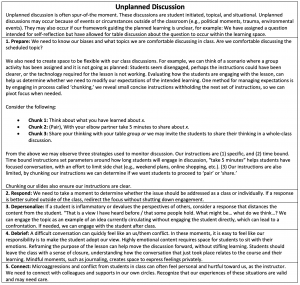

There are two forms of difficult conversations: the planned and the unexpected (see Table 3 and Table 4). Both occurrences require sensitivity to ensure conversations remain equitable, and the community continues to be a welcoming environment.

Table 3: Planned discussions

Table 4: Unplanned discussions

Now that we’ve established the difference between unplanned and planned discussions, let’s imagine what unplanned and planned discussions may look like in the context of Ezra’s universal design for learning (UDL) training module with second-year teacher candidates.

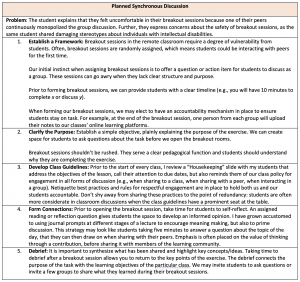

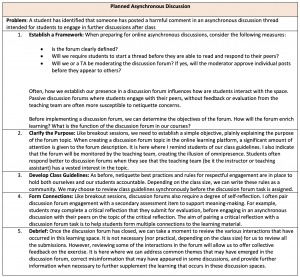

Ezra has received two emails from students that express concerns about the safety of online discussions. The first student addresses concerns that we will unpack below under the heading “Planned Synchronous Discussion.” The second student raises concerns that we will address under “Planned Asynchronous Discussion.” In both scenarios, I will share strategies that Ezra could have implemented to help mitigate the harms caused in both the synchronous and asynchronous discussion (see Table 5 and Table 6).

Table 5: Planned synchronous discussion in action

Table 6: Planned asynchronous discussion in action

Key Takeaways

Difficult conversations and controversial topics can be an important learning opportunity for students. These occurrences force us to confront our privilege, challenge our biases, and unpack the ways in which our beliefs and values shape our world view.

How Do We Set Students Up for Success When Navigating Difficult Topics?

We can model critical engagement with course material and give students the tools to scrutinize assumptions and biases. Encourage the use of appropriate language and terminology in reference to marginalized groups, from a strengths-based perspective.

What’s the Right Timing for a Difficult Discussion in a Remote Environment?

We can ensure that sensitive discussions are introduced after we have given sufficient time and space for community and capacity building .

The class’s ability to maintain an equitable learning environment can be assessed prior to a course discussion to mitigate potential harm.

Provide Content Warnings, Not Trigger Warnings

For example, “Next week we will be talking about residential schools and viewing a film that details the experiences of two survivors…” rather than trigger warnings such as “Some of you may find next week’s material distressing.”

This ensures we are providing an overview of the content without suggesting how students might feel about it. Rather than giving students an opt-out of content, we can provide our rationale for including content in the course and explain how it relates to the learning outcomes.

Misinformation

Misinformation often leads to “hot moments” in class discussions. Learning to evaluate a student’s response to difficult topics, and mediate contentious and potentially inequitable claims, is a challenge for all educators. Here are some suggestions on how we can handle these moments in the classroom:

- Establish a clear purpose.

- Include a statement in our syllabi about our commitment to equitable learning environments to pre-frame conversations.

- Uplift marginalized voices.

- Check our emotions and biases and lean on community supports when needed.

Reflecting Back on the Scenario

If we look back to our scenario, we will recall that Ezra has just finished delivering a training module on universal design for learning (UDL) to their first section of second-year teacher candidates. Let’s consider some of the strategies from above, that they could apply next time they teach:

- Ezra notes that monitoring the classroom chat on Zoom was a challenge.

Ezra may consider indicating at the beginning of class times during instruction in which students can make use of the chat feature to pose questions. Alternatively, Ezra may make use of a real time collaborative platform where students can pose their questions, and they will answer at designated moments during class time. These platforms are sometimes helpful for allowing students to ask questions that they otherwise would not ask for various reasons (e.g., worried about perceptions from the instructor or their peers).

- Ezra observes that some students appeared more confident in sharing opinions that they perhaps would not have expressed in face-to-face instruction.

Prior to the start of every class, Ezra can make use of a “Housekeeping” slide, in which they remind their students of the class policy for engagement in all forms of discussion. They may also open the class with reflexive journaling, which creates the space for thoughtful reflection before peer-sharing, or whole class discussion.

- Ezra receives an email where a student shares that they felt uncomfortable in their breakout sessions because one of their peers continuously monopolized the group discussion. The student expresses concern about the safety of breakout sessions, as the same peer student shared damaging stereotypes about individuals with intellectual disabilities.

Ezra may need to re-evaluate the instructions and types of questions they are using for breakout sessions. Some questions which require opinion or view sharing are for reflective moments. If it is anticipated that a question requires a high degree of sensitivity, Ezra should use this question as a prompt for solo-reflection. A breakout discussion should be specific and timebound, with a clear learning outcome.

Prior to the breakout session, Ezra may also hold space for students to engage deeply with a reflection question or assigned reading. This exercise gives students the space to develop an informed opinion. Before sending students away, Ezra may emphasize to the class the value of thinking through a contribution, before sharing it with members of the learning community.

- Ezra receives a second email; a student has identified that someone has posted a harmful comment in an asynchronous discussion thread intended for students to engage in further discussions after class.

Ezra may pair the discussion forum with a secondary assessment item, in which students are required to complete a critical reflection that they submit for evaluation before they are able to post in the asynchronous discussion forum. Signalling to students that discussion forums are a learning space and assessment item can help reinforce the types of dialogue we wish to see in this space. Further, Ezra may consider establishing their (and/or their TA’s) presence in the discussion forum by modelling contributions, but also by providing responses to students. Demonstrating an active presence within this space can often mitigate the netiquette concerns raised during Ezra’s UDL module.

While the strategies shared here have been helpful in my teaching practice, I think it is important to acknowledge that difficult conversations still emerge in my learning communities, despite the strategies shared above. With practice and time, we can learn to navigate difficult conversations in the (remote) classroom. I think there is humility in ‘navigating,’ as I recognize that we move through these spaces with care, and not without difficulty.

Author Acknowledgement

Thank you to Dr. Lee Airton for their continued support and mentorship. Thank you also to Wanda Beyer, Lindsay Brant, and Dr. Katherine Lewis for holding space to explore how we navigate difficult conversations in the (remote) classroom and in teacher education.