1 Chapter 1: Preparing to Integrate Discussion into Your Online Course

Kim MacKinnon, Ph.D., OCT

Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, University of Toronto

Do we really need a whole handbook about online discussions? Yes, we do. Integrating online discussions into one’s courses, like any other approaches to meaningful instruction, requires careful and intentional planning.

When instructors take a haphazard approach to integrating online discussions in their courses, they run the risk of causing confusion for their students, contributing to undue stress and, in some cases, inadvertently enabling harmful conversations to take place.

This book is intended to support instructors who are newer to online teaching (or newer to using online tools for supporting in-class teaching), but it may also be helpful for those who have already been teaching online and/or integrating online discussions into their courses for a number of years and are looking for ways to improve their practice.

The inspiration for this book emerged from the work of a small professional learning group at the University of Toronto that began early into the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020. This group of faculty members were grappling with the unexpected realities of having to shift their entire instruction to a remote learning context. Some had been teaching online for many years. Others had no prior experience with online teaching, and minimal experience with integrating online tools into their in-class teaching. In working through the challenges of adapting to remote teaching, this group quickly came to the realization that this kind of professional learning support was not only beneficial to them but also greatly needed on a broader scale across other programs and institutions. And so, work on this book began with the intent of sharing what was learned in an easily digestible and practical format for other instructors.

It should be acknowledged that online learning – and within that, the subset of computer-supported collaborative learning (CSCL) – has a decades-long research history that existed long before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and long before ”remote teaching” became of such large-scale interest. This book is not an attempt to distill that research into a short handbook. However, it does draw from this depth of expertise.

Defining What We Mean by Online Learning (also Known as “E-Learning”)

It’s essential to start this book with a brief overview of some core terminology around online learning (or to be more precise, e-learning). Having shared definitions of what we mean by e-learning can help to clarify the roles and expectations for students and instructors, and – more specific to the topic of this book – it also allows us to think about how to organize online discussions within courses in different ways.

You may find that some of these terms do not align with the ways that you notice them being taken up in your own teaching contexts. Some of that difference has to do with the fact that there is a lack of clear consensus in the field about how we ought to be conceptualizing approaches to e-learning.

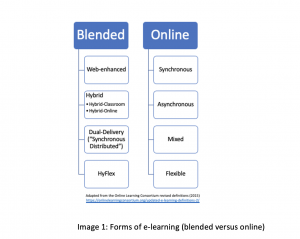

The following terms and definitions have been adapted from the Online Learning Consortium’s revised definitions for e-learning. See Image 1 for a basic visual organizer of the various terms.

Blended Forms of E-Learning

Although blended learning is sometimes treated as synonymous with hybrid learning, for the purposes of this book, blended approaches to e-learning are understood to be any approach to instruction in which there is an intentional combination of web-based learning with in-class learning. There are four basic types of blended learning: web-enhanced, hybrid, dual delivery, and hyflex.

Web-Enhanced Learning

In the case of online-enhanced learning, the assumption is that students are expected to attend their class in-person and that learning is primarily taking place through the use of in-class pedagogies. There is some uptake of web-based tools in the classroom, but they tend to be used more as an add-on than as a primary means through which learning happens.

Examples of Discussions in Online-Enhanced Courses:

- Students posting comments in a chat box or to social media while in-person instruction is taking place (referred to as “back-channeling”).

- Making allowances for students who are more comfortable sharing their ideas in a text-based format rather than aloud and in-person to post their comments in a discussion folder within the course learning management system (LMS).

- Making use of polling tools to elicit broader student engagement and sharing of ideas within in-person whole-class discussions.

Hybrid Learning

In a hybrid teaching approach, a portion of learning for all students is devoted to in-person experiences and a portion of their learning is devoted to online experiences. Students typically move simultaneously between in-person and online sessions as a class. There is some debate as to the exact proportion of online time that has to take place in order to qualify a course as truly hybrid versus online-enhanced. Rather than trying to come up with an exact formula to quantify the balance of in-person versus online, a good rule of thumb is to ask how consistently online sessions are taking place relative to in-person learning (e.g., on a fairly regular basis for all students), how intensively those online sessions are experienced relative to the overall learning experience within the course (e.g., students might describe that a significant portion of their learning is happening online), and how integral participating in those online sessions are to achieving the overall learning outcomes in the course (e.g., students would say that the online portions of their course naturally build on and/or lead into their in-person experiences). The Online Learning Consortium distinguishes between a “hybrid classroom” (in which the emphasis of course activity is on in-person learning, with some online learning) and “hybrid online” (in which the emphasis of course activity is on online learning, with some in-person learning).

Note: A “flipped classroom” approach can be considered a form of hybrid learning.

Examples of Discussions in Hybrid Courses:

- Students work in small synchronous breakout groups in Zoom early in the week to identify the main ideas for one of the class readings, which they come prepared to share in-person later in the week in mixed-reading discussion groups (this is called a “jigsaw” learning format – see for example, University of Michigan’s resource page on Jigsaws).

- Students engage in shared annotation of an assigned chapter in their course textbook (using an application such as Perusall or Hypothes.is) prior to coming to in-person learning to work on the assigned problems in collaborative groups.

- Students come to in-person learning to participate in a hands-on lesson or lab, and then spend the remainder of the week extending on their learning in the form of an asynchronous threaded discussion.

Dual Delivery (also Referred to as “Synchronous Distributed”)

In a dual-delivery course (also referred to as “synchronous distributed” by the Online Learning Consortium), each class runs in-person and online simultaneously. Students may opt-in or be assigned to conduct their learning in one mode or the other. In some cases, students may experience both in-person and online learning within the same course, but not necessarily at the same time as their class peers (e.g., in the cohort model used in many Ontario secondary schools during the pandemic, half the students were learning in-person while the other half were learning online at the same time for the same class; groups then switched between modes on scheduled days). Instructors who teach their course in a dual-delivery mode intentionally plan for instructing both students who are learning in-person and students who are learning online at the same time with the goal of creating equivalent learning experiences for both. In a true dual design, in-person learning is not prioritized over online learning (and vice versa); rather, both support a fulsome and meaningful learning experience despite the fact that students may be engaging in the learning in different ways.

Examples of Discussions in Dual Delivery Courses:

- Small group learning in which students who are in-person are engaging in conversation with others who are also in-person, in addition to students who are joining the group through videoconferencing (e.g., Zoom).

- A whole-class discussion combining in-person and online students; the online students are participating via a video-conferencing system projected at the front of the room and a camera in the classroom, which allows students who are online to see/hear those who are in-person.

- Both in-person and online students are logging into the class video-conferencing system at the same time so that there is a sense of a shared space, and so that all students have the option to interact using a shared set of web tools (e.g., the chat box).

Hyflex Learning

In a hyflex course delivery, students have the option to participate in any given class in-person, synchronously online, or asynchronously online. Students opt-in to the learning mode that work best for their individual needs at any given time throughout the course. In some cases, students may opt to conduct their learning entirely through one mode, or they may switch between modes from one class to the next. Similar to a dual-delivery mode, instructors who teach their course in a hyflex format intentionally plan for instructing both in-person and online students (though some are online at the same time, and some are online at their own pace), with the goal of creating equivalent learning experiences in all situations. In a true hyflex design, in-person learning is not prioritized over online learning (and vice versa), and synchronous learning is not prioritized over asynchronous learning (and vice versa). Rather, both in-person and online, as well as synchronous and asynchronous participation, support a fulsome and meaningful learning experience despite the fact that students may be engaging in the learning in different ways.

Example of Discussions in Hyflex Courses:

- In a hyflex learning environment, students may be working in synchronous groups that combine students that are in-person with students that are joining via a video-conferencing tool. Students participating synchronously are also referring to notes contributed asynchronously by some of their classmates. There is a commitment in these classes to documenting synchronous discussions in the class learning management system so that it builds on what has already been shared asynchronously, and so that students who are working asynchronously can likewise continue to build on what was shared from the synchronous discussions.

Fully Online Learning

In a fully online course delivery mode, the entire learning experience for students is intended to happen remotely. There are generally no in-person learning experiences for these courses.

Synchronous Online

In synchronous online courses, classes run on fixed days and times, and all students participate in remote learning at the same time (typically via a video-conferencing tool, such as Zoom or Google Meet).

Examples of Discussions in Synchronous Online Courses:

- Whole-class discussions is held within a Google Meet session.

- Small-group (“breakout”) conversations are held on Zoom.

- Students work in small groups to discuss a question posed by the instructor; each group has its own unique question. The groups are asked to document their key discussion points related to their question on a Jamboard slide using a yellow sticky note. After 10 minutes, the groups are asked to scroll through the Jamboard slides to see the other questions and group responses (this is called a “gallery walk” – see Penn State’s resource page on Gallery Walks) and add any further points the group might consider using a green sticky note.

Asynchronous Online

In asynchronous online courses, all students are permitted to carry out their learning at their own pace within a set timeframe. Typically, asynchronous courses that involve a collaborativist learning approach (Harasim, 2017) will have students move through topics together within a shared, extended timeframe to allow for self-pacing but still with the sense of having a collective learning experience.

Examples of Discussions in Asynchronous Online Courses:

- Ongoing, weekly threaded conversations are held in a shared discussion forum.

- Students add digital annotations (e.g., highlighting important sections, posting comments) to a shared reading, at their own pace within a specified time range (e.g., using Perusall or Hypothes.is).

- Students co-construct an assignment or curate a set of class resources, at their own pace within a specified time range (e.g., using Google Workspace tools).

Mixed Online

A mixed online course runs similarly to a hybrid course, where a portion of learning for all students is devoted to synchronous online experiences and a portion of their learning is devoted to asynchronous online experiences. Students typically move simultaneously between synchronous and asynchronous online sessions as a class. While there is no general consensus on the appropriate amount of time that ought to be apportioned to synchronous versus asynchronous online learning, it is advisable for instructors to consider how much consecutive time students are expected to be engaged in synchronous learning (i.e., screen time) and the workload intensity involved in asynchronous online learning activities (i.e., the volume of work relative to its benefit and given time constraints). It is not uncommon to hear students describe some asynchronous learning as “busywork” when time and workload haven’t been appropriately addressed in an instructor’s overall course planning.

Examples of Discussions in Mixed Online Courses:

- In a mixed online learning environment, one might observe opportunities for online discussions that combine those listed under the sections above for synchronous and asynchronous learning.

- Synchronous and asynchronous discussions may be designed to build off one another (e.g., a conversation begins synchronously but then continues asynchronously throughout the week).

Flexible Online

A flexible online course is primarily asynchronous by default but integrates opportunities for synchronous meetings, as needed by students. Students work at their own pace through assigned online materials and activities, and can opt to take advantage of synchronous supports that are available (e.g., booking one-to-one meetings with an academic advisor or course instructor, attending scheduled drop-in sessions with the instructor). Students are not required to meet at set scheduled synchronous times with their class peers.

Examples of Discussions in a Flexible Online Courses:

- In a flexible online learning environment, one might observe opportunities for online discussions that include those listed under the section above on Asynchronous Online learning.

- From time to time, students may meet one-to-one with an instructor or advisor, and/or in small groups that include other class peers via a video-conferencing tool.

A Special Note About “Emergency Remote Learning’” (ERL)

During the pandemic, the term “emergency remote learning” (ERL) (also called “emergency remote teaching”) emerged in response to calls from experts to make a distinction between e-learning that takes place under emergency versus non-emergency circumstances. In that sense, ERL is intended to describe a situational response to supporting academic continuity rather than a unique approach to e-learning. Over the pandemic, ERL took on many of the forms of e-learning mentioned above, and in some cases shifted between approaches as local health advisories changed. It is also important to consider that approaches to ERL may not look as “true” to the definitions listed above due to the extreme circumstances under which e-learning was taking place (e.g., in dual-delivery courses, in-person and online learning may not necessarily have been able to fully achieve experiential equivalency).

Other Considerations When Planning for Online Discussions

Aside from thinking about instructional delivery modes (see descriptions of blended and fully online learning above), there are a number of additional factors that instructors ought to consider when planning to integrate online discussions into their courses. These include:

- How will I assess an online discussion? Have I clearly communicated my expectations for the online discussion?

- How much am I asking my students to do as part of an online discussion, and how realistic is it (e.g., workload)?

- Do my students have any prior experience with engaging in online discussions as part of their learning? What do they need to know in order to engage meaningfully?

- What is my role as the instructor in the online discussion? Have I made my role clear to my students?

- How will I create an online space that is conducive to engaging in meaningful online discussions?

- How have I taken into account any potential learner needs or learning impacts (e.g., exceptionalities, language learners) such that all students are able to participate equitably and meaningfully?

Many of these topics are addressed in the remaining chapters of this handbook. In Chapter 2, Lesley Wilton shares some of the important digital literacies that are critical to student success in courses that adopt online discussions. In Chapter 3, Shelley Murphy discusses ways to be proactive and responsive to educator and student stress that can occur within learning environments and beyond. Chapter 4 by Brenda Stein Dzaldov shares insights into how to use various types of authentic assessment to support student learning through synchronous and asynchronous online discussions. In Chapter 5, Dania Wattar offers some ideas for anticipating and supporting various learner differences that can impact online discussions. In Chapter 6, Jacob DesRochers provides recommendations for managing planned and unanticipated challenging conversations that emerge in online discussions. Finally, in Chapter 7 Alison Mann offers some suggestions for ways that instructors can consider integrating alternative forms of communication into online discussions.

Chapter Format in This Handbook

Each chapter has been designed to be read on its own, as its own starting point, and/or in conjunction with other chapters. Each chapter begins with “Setting the Context,” a personal narrative that describes why the topic is important to the author; a “Scenario” that provides an example situation on the topic being discussed in the chapter; “Learning Outcomes” and “Key Terms.” Throughout the balance of the chapter, a number of self-directed learning prompts (e.g., ”Pause and Consider”) encourage readers to consider their own understandings and individual teaching contexts in relation to the ideas and examples being shared. The final section of each chapter provides a short reflection on the original scenario that allows the authors to propose what could have been done differently at the outset.

References

Harasim, L. (2017). Learning Theory and Online Technologies. London: Routledge.