2 Chapter 2: NOT busy work! The Benefits of New Literacies and Social Practices in Online Discussions

Lesley Wilton, Ph.D., OCT

York University

Setting the Context

After more than a decade of online teaching, I have come to appreciate the opportunities and possibilities that well-designed asynchronous discussions offer within a variety of communication modes. My experience with many learning management systems (LMS) and thousands of students has taught me that online discussions can support student learning in cognitive and social/emotional ways. In March 2020, when most K-12 and higher education teaching and learning moved fully online due to the COVID-19 pandemic, I was teaching in both higher education (pre-service and graduate) and elementary as a long-term occasional (LTO) teacher. I was thankful my students were somewhat familiar with using technology for learning – the kindergarten students through iPads and Seesaw and adult learners through the institutional LMSs. While most of us were unprepared for the magnitude of switching from in-class to fully remote teaching, I quickly learned that despite my comfort and experience in online teaching, what seemed most important to all levels of students was connection and a sense of belonging. The challenges faced by the teacher described in this chapter illustrate a compendium of issues that I have encountered and addressed (mainly) successfully, especially in the context of social isolation in and out of school. While I strive to create online learning environments that support a community of learners in safe and welcoming ways, there continues to be many challenges, especially as our lives outside of the formal learning context are affected by the rapidly evolving context of the pandemic. My experiences of what worked and what didn’t, and my evolving understandings of online literacies and social practices, guide my steps in this teaching journey. I hope this chapter provides some thoughtful insight for planning asynchronous online discussions in both fully online and blended learning environments.

Scenario

Ali, an educator who is experienced in designing in-person discussions to support rich learning and community-building experiences, recently began teaching online. Asynchronous learning formats can seem solitary and disconnected. After all, some students may never meet in-person. Some may see online learning as unsocial or lonely. How does one go about developing social relationships with others who are so distant and somewhat unseen? Educators, who believe that learning is a cognitive process influenced by social context, may see online discussions as an opportunity to enhance learning and facilitate community. Understanding that grades are an important incentive for student engagement, and recognizing that participation in authentic discussions requires an investment of time, Ali planned to design regular online learning discussions for a participation grade of 20%. While planning these asynchronous discussions, Ali began to grapple with these questions:

- Is this pedagogical approach simply busywork? That is, is the main goal of the activity and/or activities to validate some form of regular engagement or participation that justifies 20% of the students’ grade?

- Will the design of ongoing asynchronous discussions simply involve posing a few prompting questions related to required readings, and asking students to respond individually each week? Some might consider this approach to be self-study.

- Would students consider participating in online discussions as meeting a quota or completing a checklist – that is, meeting a required number of notes or words rather than engaging with the course content to learn?

- How can teacher time that is required to design, monitor, and grade online discussions be optimized?

- How can online discussions be designed to engage learners in reflecting and learning through authentic discussions with each other?

- How will students know how to engage in online discussions? What are the key literacies and social practices necessary for comfortable and positive engagement?

- How can asynchronous online discussions be designed to support a community of learners by fostering a sense of belonging and an environment of trust?

Learning Outcomes

- Explore how to design asynchronous online discussions to maximize student participation:

- Through clear and simple organization of the online environment;

- Through Start Here and About Week X explanations;

- By providing guidelines and modelling effective literacy and social practices; and

- By creating opportunities for students to engage in social interactions to build a sense of belonging.

- Consider ways to develop a safe and welcoming community of learners.

- Share a variety of best practices for practical and authentic design of asynchronous online learning discussions.

Key Terms: online learning communities, online learning literacies, online learning social practices, technology transience, learning management system (LMS)

Key Terms Defined

Online Learning Communities

An online learning community refers to a group of people who are learning together in a digital space. One framework that can guide our understanding of this space is the community of inquiry (CoI). More on the CoI framework can be found at https://coi.athabascau.ca/coi-model/.

Online Learning Literacies

Similar to competencies, online learning literacies facilitate effective digital ways of engaging related to communication. An example of these literacies would be creating or reading and interpreting an informative subject line for an online discussion note or entry.

Online Learning Social Practices

Contemporary online learning social practices require adaptation to the digital environment to facilitate learner interaction with course content, other learners, and the instructor. A pedagogical shift to fostering cultural ways of engaging literacy influenced by the social rules governing communication is important to designing productive online learning environments. An example of these practices would be modelling commonly adopted ways of interacting such as addressing others in an online learning environment. Frequency of posting, note content, and types of interactions are examples of social practices that learners will become familiar with in each class or course.

Technology Transience

Technology transience is described by Muilenburg and Berge (2015) as the “rapid proliferation of technology tools, the frequent update of such tools, and their ever-shortening lifespans” (p. 93). This term explains that we must constantly adapt to new ways of working with digital media. Teachers are looking to achieve pedagogical goals with evolving technologies. Our students are constantly navigating digital tools that are rapidly changing.

Learning Management System (LMS)

This term refers to the digital space in which online learning takes place.

Note: For the purposes of this chapter, the terms note, entry, or post are used interchangeably to refer to a contribution to an asynchronous online discussion.

Why Consider Literacy and Social Practices in Asynchronous Online Learning Discussions?

Many teachers and instructors find well-designed online learning discussions to be powerful pedagogical practices. Reading and writing in online discussions have been characterized as comparable to listening and speaking (Wise, Hausknecht & Zhao, 2013) . We know that reading and writing are literacy skills that have been developing since students’ early years. These literacy skills could align with the practices of listening and speaking in text discussions. Yet listening and speaking in online discussions do not necessarily involve the same set of literacy skills.

The following are some of the possible benefits related to literacy in online learning discussions.

From the instructor’s perspective, to:

- Encourage students to engage with course content and concepts in multiple ways as they build on and articulate their understandings.

- Motivate students to share their own contexts and learn from others.

- View the perspectives of students—that is, to consider if the understandings align with the course objectives, for example.

- Facilitate realignment in cases of misunderstanding.

- Create communities of inquiry and learners.

- Promote a sense of belonging.

- Foster a risk-taking environment.

- Revisit discussions and observe patterns of positive social practices.

From the student’s perspective, to:

- Engage thoughtfully in the composition of entries (not time dependent as in a face-to-face discussion) with time to revisit the content, the questions being asked and others’ responses.

- Participate in typically face-to-face classroom literacy practices considered important to learning such as exploratory talk, accountable talk, development of academic or contextual language, and transferring language forms across situations of use (Cazden, 2001, p. 169-176).

- Reflect on and articulate their understandings, and learn from others.

- Document their understandings, in a sense somewhat permanently, that can be revisited as learning is deepened.

- Develop an online identity and develop social practices with a community of learners.

Aligned with some of these benefits, an understanding of the literacy and social practices essential to online learning discussions can be helpful.

Clay’s (1991) model of literacy behaviours “respects the complexity, studies the cross-referencing of knowledge, expects different skills to be interactive, and assumes that control of this orchestration is something the [student] has learned” (p. 3). In a digital environment, literacy and social practices in discussions are enacted over distance and time by those who may not have experienced these practices previously. In an in-person classroom setting, it is possible to learn about these practices by observing others, but this process can take time. Some new online learners may not know what is expected or where to begin. It is best not to assume students know how to engage in our design of online learning discussions — the expectations should be modelled and explained.

Finally, the value of forming a community of learners must not be underestimated. Cazden (2001) believed that “as classrooms change toward a community of learners, all students’ public words become part of the curriculum for their peers” (p. 3). Well-designed asynchronous conversations can support students cognitively, socially, and emotionally.

Designing Asynchronous Online Discussions

The following recommendations guide us in the ways that Ali designs successful asynchronous online discussions to support a community of learners.

Organizing and Keeping It Simple

Ali’s goal was to organize the online discussions so that topics are clear and locating class activities is straightforward. If the online discussions are organized on a weekly basis, the title, forum, or folder can be labelled with the date and topic such as “Week 5: Oct. 12–17 – Assessment in a Digital Context.” A title like this helps students quickly identify the time frame and topic of the discussion.

Where to Begin

Introduction Space

Ali wants students to feel a part of this learning community. Ali planned to provide a place where students can introduce themselves to each other. Even if the students know each other in some way, an opportunity to share something at that moment can be created – invite them to say hello and to share something important to them. For example, students can be asked to share an image, video, or link to an important person (someone inspiring to them such as a family member, a famous person, or a popular culture reference). Encourage other students to respond in positive ways to show appreciation for the sharing that has begun. Avoid asking students to share something personal or sensitive, and sking them to invest a lot of time in this activity. It is meant to be a starting point. Offer a range of prompts and invite them to choose the ones that feel most comfortable to them. Ali will always aim to post a private response welcoming the students to the class.

Start Here

Ali knows that students may not know where to begin. Ali plans to provide a straightforward note that explains how to get started. Here are some examples of what to include in a Start Here note:

- Welcome the students with a reassuring comment – after all, some may be nervous about this new learning environment, even if it is just new in the sense of an unfamiliar teacher.

- Guide the students to the Introduction Space and encourage them to join in as they begin to create a sense of community.

- Refer to guideline notes that have been shared and explain how to locate assignments, a place to pose general questions, drop-in office hours, and other important information about the course.

Ali plans to record a video welcome message briefly introducing the course and demonstrating how to navigate the LMS. See this excerpt of a welcome message at https://youtu.be/rtm6mJAb_ss and this excerpt of a conceptual overview of another course at https://youtu.be/EInMaN0KSx0. It is important to keep these videos short – ideally two to five minutes. Multiple videos can be provided to address separate topics.

Organizing the Weekly Learning Spaces

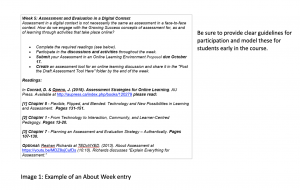

Within the weekly space, Ali created an entry that is easily visible to explain the weekly activities. For example, an About Week X entry, such as the one below, will guide learners.

The Power of Social Presence – Building Community and Having Fun with Icebreakers

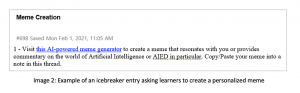

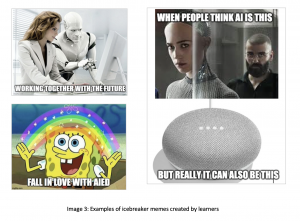

Social presence is described as the ability of online participants to project themselves socially and emotionally. In a computer-mediated environment (CME), such as an online discussion, this can be expressed through affective responses such as humour, self-disclosure, or the use of images of expression, such as avatars, emoticons, GIFs, and memes; through interactive responses by replying or referring to others; and through cohesive responses such as referring to our group, we, or us, and indicators of community building and belonging (Rourke et al., 2001). Within the weekly activities, Ali considered introducing learners to each week’s discussions by first engaging them in an icebreaker activity to facilitate social presence. Such an activity is not primarily intended to deepen learning but rather to facilitate community building. Icebreakers can involve engaging in a fun activity such as an avatar creator, meme creator, or sharing activity to help learners get to know each other in this digital space. The following is an example of such an activity.

Other icebreaker activities might include asking learners to share a picture of their ideal place to visit, a favourite meal, a most inspiring quote, two truths and a lie, an online resource, and even sharing the results of an activity such as https://quickdraw.withgoogle.com/. The possibilities are endless – as long as they are designed to be inclusive and welcoming. In addition, after modelling this activity, Ali intends to invite students to lead the icebreaker activities to increase participation and engagement.

Organizing the Discussion

When online discussions take place in large groups, students can become overwhelmed with many responses to read in one space. Discussions are best organized in small groups of six to eight. Ali created a separate section within these small groups for each discussion question. It is best if each week’s activities are organized in a consistent manner so that learners know where to look for the readings, the icebreakers, and questions to be addressed by their groups. Ali considered many options for dividing students into groups. Here are a few examples of groupings in playful forms:

- Favourite meal of the day (breakfast, lunch, dinner).

- Preferred times of the day to learn (early bird, midday, night owl).

- Favourite entertainment types (comedies, romance movies, documentaries).

- Ideal vacation place (home, a place with a beach, a place with lots of snow).

- Preferred season (summer, winter, shoulder seasons).

- Favourite weather (rainy, snowy, sunny).

- And even Harry Potter houses.

Creating Engaging Discussions to Foster Deep Learning and Engagement

Guiding us with three strategies for better online discussions, Sherry (2020) suggests we scaffold the discussion by encouraging informal language to allow our learners time to familiarize themselves with the language of our content. Ali will encourage multimodal engagement with visual, audio, and video responses but will also be mindful that these modes may be new to some, so simple text participation is valued, too. Ali will avoid asking “yes” or “no” questions and will “invite multiple, complex interpretations – open, high-order thinking (O-HOT) questions – they spark more responses and more substantive discussion” (p. 11 ). It is also helpful to prompt for elaboration — what made us think that or what does the author want us to think? We are aiming for conversation and engagement multiple times through the week.

Ali’s design of the discussions will be mindful of what Hewitt (2005) refers to as clunkers that shut down discussions, such as personally addressed responses like “Dear Zoe,” off-topic notes, superficial comments, and agreement without expansion. Ali will intentionally remain less visible in discussions since instructor responses can be perceived as clunkers, too, because they can appear to give the right answer, even if there isn’t necessarily one correct response.

Finally, Ali will invite small groups of students to conduct the weekly discussions to build engagement and raise learner confidence by reframing course content to others. This opportunity will allow the students to become subject matter experts (SMEs) to a limited degree, and will allow them to experience the processes involved in planning a weekly discussion. This opportunity may also improve their participation in other weekly discussions once they understand the underlying goals of designing a discussion to deeply engage with the content and other students.

Guidelines for Online Discussions

One way to help learners develop literacy and social practices in online learning discussions is to provide guidelines. This strategy is most important because many learners may be drawing on experiences aligned with social media, which are different from a formal learning environment or experiences with other courses or teachers.

Asynchronous discussions can be designed to encourage students to respond to a question and then engage with others by responding to another’s note. Ideally, an online learning discussion should have multiple interactions as students engage with the content, the instructor, and with other students. After reading an article, watching a video, or participating in an activity to become familiar with the intended content, students will engage with the instructor and their peers as they share their understandings, typically in text form.

Here is an example of Guidelines for Online Discussion Contributions that Ali plans to adopt while developing promising practices in online teaching:

What makes a good note?

These are some questions to ask yourself about your contributions, to check whether you are on the right track:

- Does the contribution advance the current topic?

- Is it concise?

- Are there connections or links to the course content or other students’ ideas to support your thoughts?

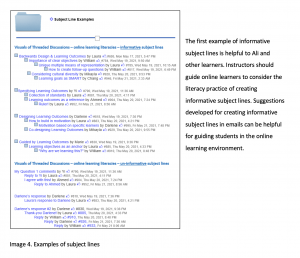

- Is there an informative title for the note or entry? Does it set the context, indicate its topic and or encourage engagement for example? It is best to avoid “Reply” or “Reply to” because this does not tell us what this entry is about. See below for more on this topic.

- Does it do one or more of the following: share knowledge, pose well-formulated questions, constructively criticize ideas, build on what others have contributed?

- Is it directed to the whole group and does it provide substance? Messages that are directed to an individual should be sent privately. Entries of general agreement without adding to the discussion should be minimized. If the LMS supports a like function, this can be used to encourage peers.

- Does it relate to the course content or offer new relevant resources?

- Are the contributions spread throughout the topic time period, rather than at the last-minute where it will be unlikely to receive responses from others? Is this contributing to a conversation rather than simply responding to a reading without drawing others into the conversation?

Ali will consider that the goal of “concise” in point 2 above could be guided by a word count, but it may be best to avoid assigning a word count so there isn’t a quota.

Guidelines for Creating Informative Subject Lines — a New Literacy of Online Learning Discussions

One example of a literacy practice that online students will not typically have imported from face-to-face discussions is developing subject lines. When participating in an in-person discussion, we would not typically announce what we are about to say, nor would we wait until the receiver of the information chooses to further engage. Yet in an online discussion, we expect that participants will design a succinct and informative subject line. The title of a discussion entry can help readers decide on the relevance or importance of the note’s content before viewing. Not every note by other students needs to be read. The subject line can also act as a way finder, to quickly identify a note one might want to revisit.

Subject Line Scenario

Ali has provided an article on backwards design and learning outcomes and has asked students to respond in an online discussion. Responses from students could be represented in one of these scenarios.

Some helpful suggestions for creating an informative subject line are:

- Be succinct.

- Avoid punctuation and unnecessary capitals.

- Consider leading the reader – for example, Learning theorists in this digital world would say…

Salutations in Discussion Posts as a Social Practice

Studies indicate that addressing a specific learner in a general note will affect engagement by other learners (Hewitt, 2005). In general, it is not necessary to include a salutation (or a closing) in a discussion note. If the same discussion was taking place in a face-to-face classroom, shared thoughts can be addressed to anyone in the discussion. Some suggest that addressing only one learner can indicate to others that the note is not intended for them and can discourage others from responding. To easily build on others’ opinions, many LMSs will allow links to notes written by others. Such links, embedded in a note, are ideal as the reader can revisit relevant ideas in other notes referred to by the writer.

Consideration of Student Participation Patterns and Social Practices

Finally, it is important for Ali to get to know the students and their patterns of participation. A study of participation patterns found that quiet participation does not necessarily indicate disengagement or lack of interest (Wilton, 2019). Some learners prefer to learn by reading what others have to “say” but are not comfortable posting a lot. This preference makes their participation less visible. English-language learners, for example, may require more time to compose and post a response. Participation measures should consider time spent reading others’ responses. Ali is mindful of the importance of getting to know all students.

Reflecting Back on the Scenario

Although inexperienced in online teaching, Ali designed an asynchronous discussion environment to be inclusive, to build a sense of community, and to foster a community of learners. Ali is not drawing on discussions to create busy work that students may not see as helpful to learning. Instead, online discussions are designed to deeply engage with the learning content, the teacher when needed, and each other. Here are a few key components of the design:

- Ali is supporting online literacies and social practices. Not all students will know what to do in this learning environment. Ali provides clear guidelines and organizes in a consistent and easy-to-navigate format using Start Here and About Week X explanations.

- Ali is fostering a sense of belonging in this community of learners through cognitive, social, and emotional supports. Ali is providing a space for student introductions, icebreakers, and discussions as conversations to engage all learners.

- Brief Introduction and Course Overview videos are being recorded and shared by Ali to enhance teacher social presence and provide information to learners in multimodal ways.

By supporting online literacies, social practices, and a sense of belonging in asynchronous discussions, Ali’s community of learners will engage with each other through online cognitive, social, and emotional supports. Now, more than ever, we must provide our students with comfortable and supportive digital spaces in which to learn together.

References

Cazden, C. B. (2001). Classroom discourse: The language of teaching and learning (2nd ed.). Heinemann.

Clay, M. (1991). Becoming literate: The construction of inner control. Heinemann.

Hewitt, J. (2005). Toward an understanding of how threads die in asynchronous computer conferences. The Journal of the Learning Sciences, 14(4), 567–589.

Muilenburg, L. Y., & Berge, Z. L. (2015). Revisiting teacher preparation: Responding to technology transience in the educational setting. The Quarterly Review of Distance Education, 16(2), 93–105.

Rourke, L., Anderson, T. Garrison, D. R., & Archer, W. (2001). Assessing social presence in asynchronous, text-based computer conferencing. Journal of Distance Education, 14(3), 51–70.

Sherry, M. B. (2020). Three strategies for better online discussions. A New Reality: Getting Remote Learning Right, 77(10), 36–37. https://www.ascd.org/el/articles/three-strategies-for-better-online-discussions

Wilton, L. (2019). Quiet participation: Investigating non-posting activities in online learning. Online Learning Journal, 22(4), 65–88. https://olj.onlinelearningconsortium.org/index.php/olj/article/view/1518

Wise, A.F., Hausknecht, S., & Zhao, Y. (2013a). Relationships between listening and speaking in online discussions: An empirical investigation. In N. Rummel, M. Kapur, M. Nathan, & S. Puntambekar (Eds.), Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Computer Supported Collaborative Learning Vol. I (pp. 534–541). Madison, WI.

Helpful Resources

Bates, A. T. (2019). Methods of teaching with an online focus. In Teaching in a digital age (2nd ed., pp. 121–165). OpenTextBC. https://opentextbc.ca/teachinginadigitalage/part/chapter-6-models-for-designing-teaching-and-learning/

Cleveland-Innes, M., & Wilton, L. (2018). Guide to blended learning. Commonwealth of Learning. http://oasis.col.org/handle/11599/3095

Conrad, D., & Openo, J. (2018). Assessment strategies for online learning. Athabasca University Press. https://www.aupress.ca/books/120279-assessment-strategies-for-online-learning/