4 Chapter 4: Authentic Assessment in Online Learning

Brenda Stein Dzaldov, Ph.D., OCT

Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, University of Toronto

Setting the Context

As a former Ontario teacher and principal, I began working at a large Ontario university after receiving my PhD in 2012. During my 25 years in Ontario schools, I spearheaded and supported many successful school improvement plans, and one idea was foundational in all my work: Assessment practices that were transparent to students inspired promising instruction and meaningful learning. I quickly remembered that, in the university world, assessment of learning (or evaluation/grading) was the main means of assessing students, often through major papers, assignments, or exams. Bringing my own experiences with assessment to university teaching, I integrated ongoing feedback into my assessment practices, making success criteria clear and providing opportunities for students to co-construct assessment criteria and use peer and instructor feedback to improve their own learning. I also used my students’ classroom discussions and work samples to guide my instruction, to the extent that a 12-week, 36-hour course allowed.

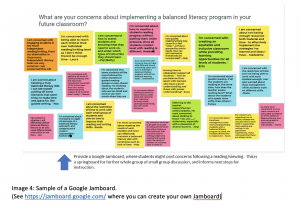

In March 2020, when our courses moved fully online due to the COVID-19 pandemic, I was suddenly presented with the challenge of using synchronous and asynchronous environments simultaneously in my courses but had no prior experience with online teaching. Yes, I had used a learning management system to post assignments, PowerPoint slides and articles, but that was the extent of my expertise with using technology in my teaching. At first, I spent most of my time just trying to figure out how to run my classes on Zoom; however, I soon joined a community of instructors and, together, we learned how to modify our typical in-person learning practices to support intentional online discussion, teaching, and learning. As 2020 turned to 2021, we moved into other supportive technologies such as pre-recording and editing lectures, using apps like Google Jamboard, Google Slides with add-ons and investigated various ways to understand, promote, and assess online discussions. The obvious challenge of meaningful and authentic assessment that supported learning became my own focus for improvement. Obviously, not everything I tried worked, but what follows is what I learned and some of the applications that worked!

Scenario

BSD is a university instructor with more than 10 years of experience. When she began teaching courses online in March 2020, she made many assessment errors, including trying to grade asynchronous discussion threads without clear success criteria or judging participation by counting the number of times a student posted a response or spoke in the whole-group Zoom meeting. She realized she was assigning marks and judging her students through general impressions and attendance. Her students began asking, “What counts for this part of the mark?” or “What if I’m not comfortable speaking in a whole group on Zoom?” BSD’s goal was to focus on authentic assessment, to create opportunities for her students to use the “skills, knowledge, values and attitudes they have learned in the performance context of the intended discipline” (Conrad & Openo, 2018, p. 5; Goff et al., 2015, p. 13 ). She put a lot of effort into avoiding the common pitfalls of assessment and evaluation she had already experienced while teaching university courses (e.g., too much marking/grading, unclear expectations that were difficult to explain to students, lack of opportunities for learners to act on feedback, discussions and lectures that were disconnected from the learning objective). This new online learning environment gave her the chance to implement many ways to engage with authentic assessment using online discussion that she would strive to implement in a way that would neither privilege nor exclude any of her post-secondary learners.

Through an examination of some of the tools used in BSD’s 36-hour online course, this chapter will seek to support university educators to challenge conventional assessment processes and leverage the online environment to create authentic assessment and learning opportunities for post-secondary students, without having to “mark” every task to make it relevant or meaningful for learning.

Learning Outcomes

- To consider the various types of assessment (assessment for, as, and of learning) that can be used for online discussion in synchronous or asynchronous learning environments.

- To share a variety of practical, authentic approaches to assessment through examples of online discussion and interactions.

- To challenge current conceptions of participation, engagement, and professionalism in assessing learning online.

Key Terms: asynchronous, synchronous, assessment as/of/for learning, apps, learning management system

Understanding Online Assessment

Guiding Principles for Assessment

It is imperative that we consider the fundamental principles and research that guide assessment and evaluation. Assessment must be viewed through an intersectional lens in order that we may assess students while considering the impact of their backgrounds and experiences on learning.

To ensure that assessment, evaluation, and reporting are valid and reliable, instructors must consider practices that are:

- Fair, transparent, and equitable for all students; assessment must be implemented with a consideration of your own underlying beliefs/biases about the nature of assessment, tools for assessment, and “acceptable” standards (Montenegro & Jankowski, 2017).

- Supportive of all students, including those with special education needs, those who are learning the language of instruction (English or French), students who are gender diverse, Black, people of colour, and/or Indigenous peoples.

- Carefully planned to relate to learning goals and, as much as possible, to the interests, learning styles and preferences, needs, identities, and experiences of all students.

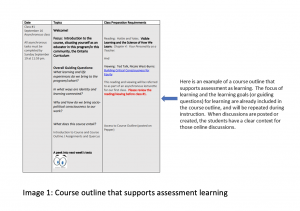

- Communicated clearly to students at the beginning of the course and at other appropriate points throughout the course (creating redundancies that support learning).

- Ongoing, varied in nature, and administered over a period of time to provide multiple opportunities for students to demonstrate the full range of their learning (Government of Ontario, 2020-21).

Promising Assessment Practices

As you assess in the post-secondary environment, it is imperative that some promising assessment practices be included in online teaching, even though it might create the necessity for additional instructor organization at different times (e.g., not all the “marking” is at the end of a learning cycle). Promising assessment practices include:

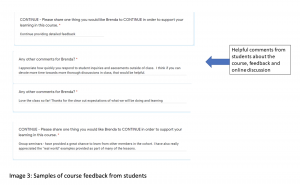

- Providing ongoing descriptive feedback that is clear, specific, meaningful, and timely to support improved learning and achievement.

- Supporting students to develop these self-assessment skills to enable them to assess their own learning, set specific goals, and plan next steps for their learning.

- Providing multiple means of participation and engagement in learning, considering your own underlying beliefs about the nature of participation and what factors inform your beliefs.

Three Types of Assessment: Assessment for Learning (guiding instruction), Assessment as Learning (student-involved assessment), and Assessment of Learning (grading)

In Ontario schools and across post-secondary institutions, assessment is no longer understood simply as grading. Instead, it is the process of gathering information that accurately reflects an individual’s learning (Ontario Ministry of Education, 2010, p. 28).

There are three types of assessment that support learning, whether in online or in-person environments:

Assessment for learning “is the process of seeking and interpreting evidence for use by learners and their teachers to decide where the learners are in their learning, where they need to go, and how best to get there” (Assessment Reform Group, 2002, p. 2).

Some tools used for “assessment for learning” that are related to online discussion include:

- Descriptive feedback on assignments provided by peers and/or the instructor prior to submission for grading, which can be shared in a synchronous or asynchronous online discussion.

- Tickets in the door/out the door (i.e., mini reflections at the beginning or end of the lecture) based on text read/viewed or lecture given, which could be shared in an online discussion format.

- Small/large discussion groups (e.g., breakout groups) to support application of skills and knowledge learned through reading/viewing and applied to authentic situations relevant to the discipline.

Assessment as learning “focuses on the explicit fostering of students’ capacity over time to be their own best assessors” (Western and Northern Canadian Protocol for Collaboration in Education, 2006, p. 42). Information gathered is used by students to monitor their own progress towards a learning goal, make adjustments, reflect on their learning, and then set their own goals for new learning.

Some tools for “assessment as learning” that are related to online discussion include:

- Access to clear learning goals and success criteria/rubrics for a particular learning goal/objective/assignment, which can be discussed and clarified in online discussion with peers or the instructor.

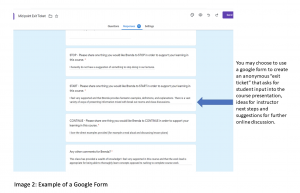

- Students’ written reflections on their own learning and progress towards goals (e.g., responding to prompts such as, “What would you stop, start, continue?” “What did you learn?” “How do you know?” “How will this new learning impact your understanding of real-world problems?”).

Assessment of learning “is the assessment that results in grades which are intended to reflect how well a student has learned. It often contributes to pivotal decisions that will affect students’ futures. It is used to summarize learning at a given point in time, and make judgments about the quality of student learning, based on established criteria, to assign a value to represent that quality” (Ontario Ministry of Education, 2010, p. 31).

Some tools for “assessment of learning” that are related to online discussion include:

- Tests/exams that can include time for collaborative discussion of questions in synchronous or asynchronous discussion groups.

- Graphic representations of learning (e.g., mind maps, simulated environments, slide shows, audio or video files), which can be shared/discussed and given feedback before final submission.

- Short, written reflections that focus on application of ideas worth small portions of an overall grade and that include feedback to support future reflections.

- Students discussing and co-constructing/sharing criteria to guide grading.

Authentic Assessment Practices that Promote Online Discussion

Although university educators may default to grading essays and tests or conceptualizing participation in a particular way that privileges or excludes certain learners, assessment can be made more authentic by using one or more assessment for/as learning practices. Instructors can provide explicit and varied criteria for engagement in their instructional practices. Discussion and feedback along the way can support students to move forward and complete a graded assignment more meaningfully.

Authentic assessment through discussion for learning can occur in both/either synchronous or asynchronous online environments.

We can place students into small group breakout rooms (synchronous) or into pre-created small groups (asynchronous) with a particular discussion question or prompt. If this is done synchronously, assign a reporter who will share specific highlights of the discussion back with the whole group.

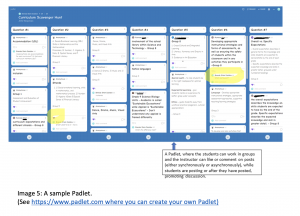

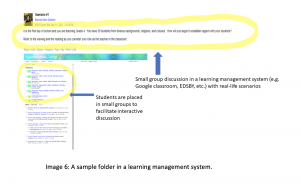

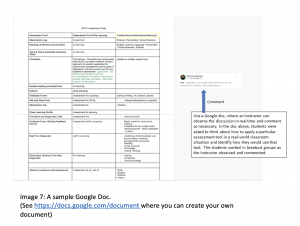

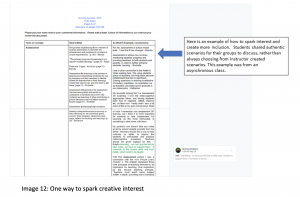

We can provide interactive documents or formats for students to “discuss, comment, or add ideas” when discussing information. We can choose any of the following tools: a Google Jamboard (Image 4), a folder in a learning management system (Image 5), a Padlet (Image 6), or a Google Doc (Image 7) to accomplish this task. When we use these tools, we will have a permanent record of discussion to support our planning and instruction.

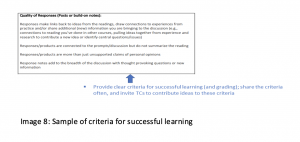

There are many ways for our students to participate actively in the assessment process. One way is to ensure that the criteria for assessment are clear (see Image 8). We can be open to adding/clarifying criteria if students make a reasonable case to consider.

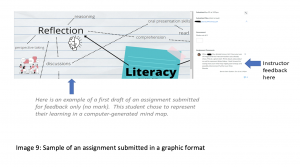

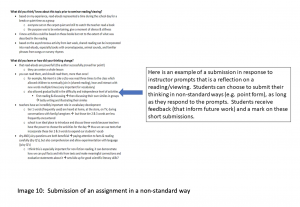

In order to make assessments available to a wide range of learners, we can lean away from always expecting/privileging one type of submission (e.g., usually written). We can give students the opportunity to share their thinking in multiple ways (e.g., point form, audio or video submissions, graphic submissions). See Images 9 and 10 below.

Make sure to provide supports for students who might require them (e.g., live transcripts, closed captions, notes, slides) in order to improve access to discussion and learning, and make assessment more authentic.

Give choice and feedback along the way, even when grading, to support students to assess their own learning and plan/share their own next steps.

Grading Participation, Engagement, and Professionalism in Online Discussions

Engagement and professionalism, or participation, are challenging areas to assess or evaluate fairly.

Some instructors use:

- Attendance lists.

- Number of times a student speaks in a whole group discussion.

- Number of times a student posts in an online, threaded discussion.

- Quality of posts and add-on notes in online, threaded discussion.

- Whether a student leaves their camera on or off during discussion (e.g., large or small group).

If you choose to use any of the above criteria for assessing professionalism, remember:

- Be proactive and prepared to share your rationale for students’ grades.

- Consider ways your understanding of professionalism may exclude some students (e.g., whole-group participation).

- Think about which students might be privileged or excluded by how you conceptualize participation in the online environment.

- A participation mark might benefit those learners who are more ready to get online and post their first thoughts, while disadvantaging folks who prefer to take the time to reflect more deeply before sharing their ideas (Openo, p. 165).

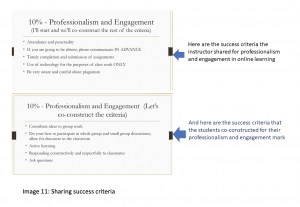

- Students must be aware of the criteria for success; once you have decided on the success criteria, ask the students what other criteria they believe would be important for their professionalism/engagement grade (see Image 11 for an example).

- Equity issues will impact some students more than others (e.g., poor Wi-Fi, people in the background, discomfort with sharing in a whole group, discomfort with writing in a chat based on writing skills).

- Students can be very engaged in learning, but not comfortable participating orally; provide choice and communicate the right to pass.

- When asking students to engage in discussion, we can repost success criteria to create redundancies and provide support.

- We can provide exemplars (samples or models for expected responses), but allow for choice of format.

- We can read the notes/discussion created by our students, to give some specific and some general feedback along the way. As students respond to comments/questions from us and others, you can use these as examples of their thinking, participation, and engagement.

- We can give students opportunities to comment on another student’s questions/responses with constructive ideas that are informed by their own experiences and/or learning in our courses.

- We can support online discussion by sharing links between students’ ideas in various discussion groups (either synchronously or asynchronously).

- We can allow students to participate anonymously at times; at other times, we can have students include their names, so we can use the information as assessment for learning.

- We can allow students to have input into assessing their own participation, based on the criteria set at the beginning of the course (Conrad & Openo, 2018, p. 165).

Reflecting Back on the Scenario

Online discussions and assessments have changed significantly in BSD’s courses. She can use a variety of online tools to track and engage with online discussions. She organizes small groups, sometimes randomly and sometimes based on the assessment information she has gathered. Students are given the opportunity to submit assignments for descriptive feedback, from peers and from herself. As she gives feedback on discussions and assignments, she uses many redundancies, repeating information in various places (reposting learning goals and success criteria, assignment expectations). She uses authentic scenarios from both students’ lives and her own experiences to create opportunities for students to apply new learning to authentic situations. She still finds herself doing a lot of reading and commenting during her students’ discussions, as well as marking their final products, which are submitted based on choice of format. For BSD, assessment of learning is much clearer and much more aligned with goals for the course. Clearly, the opportunities to discuss and act on feedback makes a difference for her students’ online learning.

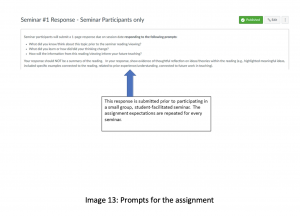

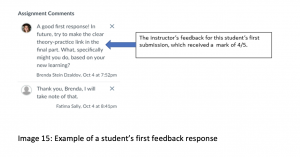

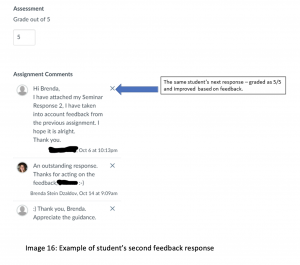

Finally, here is an interaction that sums up assessment that guides instruction and supports students’ own next steps towards learning (follow Images 13 to 16). Take a small step, try one idea, and challenge conventional assessment processes in the online environment to create authentic assessment and learning opportunities for your own post-secondary students.

Students were given a reflection assignment to complete asynchronously for each reading/viewing prior to the class for that content area. They must complete four out of five over the time in the course. First, students are given prompts for the assignment.

The student submitted their first response and received a mark as well as actionable feedback.

The student’s next response was excellent, and addressed issues shared in the feedback.

References

Assessment Reform Group. (2002). Assessment for learning: 10 principles. Research-based principles to guide classroom practice. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/271849158_Assessment_for_Learning_10_Principles_Research-based_principles_to_guide_classroom_practice_Assessment_for_Learning

Conrad, D., & Openo, J. (2018). Assessment strategies for online learning: Engagement and authenticity. Athabasca University Press.

Goff, L., Potter, M.K., Pierre, E., Carey, T., Gullage, A., Kustra,E.,…& Van Gastel, G. (2015). Learning outcomes assessment: A practitioner’s handbook. Toronto, ON: Higher Education Quality Council of Ontario. Learning Outcomes Assessment A Practitioner’s Handbook (uwindsor.ca)

Government of Ontario. (2020–21). Assessment and evaluation. Curriculum and Resources. https://www.dcp.edu.gov.on.ca/en/assessment-evaluation/fundamental-principles

Montenegro, E., & Jankowski, N.A. (2017). Equity and assessment: Moving toward culturally responsive assessment. National Institute for Learning Outcomes Assessment.

Ontario Ministry of Education. (2010). Growing success: Assessment, evaluation and reporting in Ontario’s schools covering grades 1 to 12. https://www.dcp.edu.gov.on.ca/en/assessment-evaluation/fundamental-principles,

Western and Northern Canadian Protocol for Collaboration in Education. (2006). Rethinking classroom assessment with purpose in mind: Assessment for learning, assessment as learning, assessment of learning. https://open.alberta.ca/publications/rethinking-classroom-assessment-with-purpose-in-mind