3 Chapter 3: Cultivating Mental Health, Well-Being, and a Culture of Care in Online Teaching and Learning Environments

Shelley Murphy, PhD

Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, University of Toronto

Setting the Context

Just two short years ago, I was decades into my teaching career and finally beginning to feel as though I might have a grip on what it means to be a skillful educator. I research, study, write about, and teach on the topic of mindfulness in education and supporting both educator and student well-being. In my role as a former elementary teacher and now as a teacher educator at the University of Toronto, I have been steadfast in my commitment to ensuring well-being is front and centre in the learning environments I co-create with my students. Enter the COVID-19 pandemic and the lightning speed that was needed to move to online teaching and learning. In truth, with absolutely no experience teaching virtually, this tested my basic ideas about instruction and what was possible in the online teaching environment. I wondered how on earth I would compensate for the lack of immediate physical infrastructure that had always supported my practice of foregrounding belonging and connection, well-being, and meaningful discussion. Pre-pandemic, I would not have elected to teach virtually. I realize now this thinking was, in part, because I felt sorely ill-equipped to do so and because I wasn’t confident that I could establish the same connection with my students or support them to cultivate connection and meaningful dialogue with and amongst each other. To my surprise, as I began to stumble my way through learning how to teach online, I also figured out ways to continue to forefront student and educator well-being. I adapted tried-and-true in-class strategies for use in the online environment and I also developed and learned new strategies that I had not considered before. I understand now that as I entered this uncharted territory of online teaching, I was not starting from scratch. Instead, I have been leveraging my experience and understanding and using them as guides for enacting caring, inclusive, and responsive pedagogy in a different teaching and learning terrain. This chapter outlines some of what I have leveraged and learned along the way toward this end.

Scenario

Kelly has just finished a virtual meeting with a student who has reached out for support because they are having a difficult time coping with increasing levels of stress and anxiety; they have concerns about its impact on their well-being and their academic responsibilities, including their ability to feel comfortable participating in discussions in online environments. Particularly, over the last few years, Kelly has noticed an increased need and demand for responding to students’ mental health and well-being. The number of students reaching out to her has increased exponentially given these challenging times. She recognizes that because of her frequent interaction with students, she is uniquely positioned to offer both proactive and responsive support, yet she feels sorely ill prepared to do this work. Kelly, like many of her students, has also been experiencing stress and anxiety herself. Some of it is related to the rigours and expectations of her role, some of it resulting from systemic barriers, and some of it related to meeting the range and complexity of the well-being needs of students in the changing teaching terrain of an ongoing pandemic. Beyond responding to mental health-related accommodation requests and the obvious step of referring her students to the university mental health centre, Kelly is wondering how her new online teaching environment can be set up in a way that is more conducive to centering a pedagogy of care, helping her students feel more comfortable engaging in online dialogue and, more generally, helping them thrive. She would also like to know how to better attend to her own well-being needs before reaching the burnout stage.

Learning Outcomes

- Consider mechanisms of the stress response.

- Understand the importance of promoting and protecting our own well-being as online instructors.

- Promote student well-being and learning through a pedagogy of care in online environments.

- Enact on-line tools and strategies to support and resource our students and ourselves.

- Cultivate an inclusive learning environment that supports greater social-emotional ease for students engaged in online discussion (synchronous and asynchronous).

Key Terms: educator well-being, student well-being, stress, pedagogy of care, tools and strategies, online teaching environment, online discussion

Introduction

We may ask ourselves why there is a chapter focused on faculty and student well-being within a book focused on designing meaningful discussion in online courses. Good question. This chapter pulls back the lens for a broader perspective on how we might support our students and ourselves through a compassionate and restorative approach to teaching and learning. This type of approach allows us to support student-centred learning and discussion in our classrooms more skilfully while also resourcing ourselves in, for, and through this work. This chapter will outline some considerations for paying attention to our own well-being as an entry point for greater resilience and thriving in our roles as instructors and beyond. It also outlines strategies for enacting a pedagogy of care for supporting the mental health and well-being of our students; by doing so, it has the potential to open a portal to meaningful dialogue, learning, and well-being in our classrooms.

Equity Lens

It is important to note that while the stress and anxiety discussed within this chapter are framed as wellness issues, they are also deeply influenced by harmful institutional, social, and political conditions. When we view mental health and well-being through an intersectional lens, we recognize the ways in which racism, sexism, ableism, poverty, homophobia, lack of BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, People of Colour) representation, and so on can negatively impact well-being. Additionally, the COVID-19 pandemic has underscored discriminatory and unjust structures that have disproportionately impacted marginalized communities. To ignore these realities does a disservice to both ourselves as educators and to our students. The strategies found within this chapter are not offered as a means of helping faculty and students adjust to experiences of stress, anger, and discontent in response to systems of oppression. They are offered with the hope that they are counterbalanced with a commitment by educational leaders to critically analyze how the conditions that contribute to these experiences in students and faculty can be transformed.

Understanding Mechanisms of the Stress Response

There are myriad ways we can help our students and ourselves build resilience to and better manage stress. This begins with understanding the mechanisms of our own stress response. When we have a greater understanding of how stress and our nervous systems work, it can help us to manage our stress much more skillfully. Let’s begin by distinguishing between a stressor and stress itself. The American Psychological Association (n.d.) defines a stressor as a force or condition that results in physical or emotional stress. Put simply, a stressor is an event that causes us stress. Stress, on the other hand, is our physiological and psychological response to one or a combination of stressors.

It is often assumed that stress is always associated with negative experiences. In fact, it’s not the case. There are two different kinds of stress: positive stress (eustress) and negative stress (distress). Starting a new job or relationship, learning a new skill, or giving a presentation are all examples of when we may experience stress as positive. This type of experience often provides us with a surge of energy, motivation, focus, and flow; it typically evokes positive feelings in us. In contrast, negative stress is experienced when a current situation or future event is interpreted as threatening or harmful. Experiencing a breakup, waiting for medical test results, or facing a pandemic can lead to distress and overwhelm when we are not physically, mentally, or emotionally equipped to manage the demand we are faced with.

Our personal experience of stress (i.e., how it lands in our bodies and minds), depends on myriad factors, including genetic, social, cultural, physical, psychological, environmental, and behavioural. The same stressor will impact different folks in different ways depending on our interpretation of the stress, our lived experiences and how well our nervous systems are equipped to handle the stress. Each of us has a threshold, so to speak, of how much stress we can metabolize or manage before it negatively impacts our daily lives. Luckily, we are not passive recipients of stress; we and our students can learn to mitigate and respond effectively to the challenges of a stressor through cognitive, physical, and environmental considerations. This chapter will outline a few of these considerations.

Instructor Well-Being

Though instructors are ultimately responsible for their own well-being, it is the employer’s responsibility to provide the conditions that support and not detract from thriving in the workplace. So, it is important to note that a focus on well-being and self-care for faculty in this chapter is not an attempt to bypass the primary need to ensure our work environments are alleviating or avoiding the causes and conditions that give rise to emotional and physical distress in the workplace. Workplace culture is often a major roadblock to health and well-being. It is right to expect that work environments provide the conditions necessary to support the mental health and well-being of its instructors. It is equally important to recognize our need and responsibility to focus on our own wellness.

As educators, we likely give a lot of ourselves in service of supporting the learning, growth, and well-being of others. By focusing on our own wellbeing, we enact an essential counterbalance. The importance and benefits of intentionally focusing on our own well-being are often overshadowed by feelings of guilt for doing so. However, there are myriad reasons why prioritizing our own well-being is of benefit to us and our students. Think of your role as an instructor in an online environment as being at the helm of the nervous system of the classroom. Research bears out the impact of what is called stress contagion and the ripple effect of educators’ levels of stress, fatigue, and burnout. When we are at ease, our students are more likely to be at ease. Reciprocally, it is also true that when our students feel less stressed and more at ease, we are likely to feel less stressed as well. Focusing on our well-being and the well-being of our students is mutually beneficial.

Here are a few recommendations:

Reach out to colleagues for support: Since many faculty members work independently, they often lack embedded structures through which they can engage in mutual support. Almost immediately after the pandemic began and my teaching work switched to online education, I was invited to join an informal bimonthly meeting with colleagues. Our intention was to support each other through a new and uncharted territory of teaching through the pandemic – with half of us being completely new to the online environment. These meetings, which continue today, have led to meaningful professional development and instructional improvement for all of us. Perhaps as crucial is that they have positively contributed to a sense of connectedness, collegiality, and well-being.

Avoid saying yes on the spot: This is somewhat different from “just say no.” As educators, we are often confronted with the never-ending stream of requests for service. At times, tenure and promotion are highly dependent on this service. Rather than being caught off guard, it can be helpful to intentionally plan and prepare a process for taking time to evaluate and respond to these requests ahead of time. This process may begin with giving ourselves time to think about whether the “ask” is feasible, important, or of interest to us. If the answer is no, it can help to remember the words of economist Tim Harford, who said, “Every time we say yes to a request, we are also saying no to anything else we might accomplish with the time” (Harford, 2015).

Recognize when we are moving into a stress response: How well-equipped we are to manage stress before it escalates to unhealthy levels influences its impact. A certain level of stress acts as a natural protector. It guides our behaviours in ways that are meant to help keep us safe. For this we can thank the natural intelligence and wisdom of our minds and bodies. At the same time, we need to be intentional about making sure that we are not getting caught in an ongoing and constant loop of stress in ways that are no longer protective. Chronic activation of the stress response can take its toll on our physical and psychological health. So, we need to learn how to turn the alarm bells off when they are not needed (Murphy, 2019).

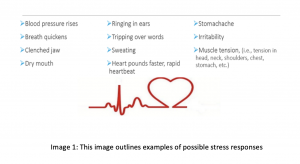

One of the first steps of learning how to manage stress is recognizing our unique expressions of stress. Each of us has a different early signal or indicator for when our levels of stress are about to escalate beyond what we can manage. For some folks, these early warning signals may come in the form of shallow breathing, irritability, muscle tension in the chest or belly, or feelings of heat and tingling in the extremities. Image 1 includes examples of stress cues shared by fellow educators.

When we become attuned to our unique signals of early stress, we are more able to interrupt a larger cascade of stress responses with coping tools and calming strategies.

Have a plan for inviting our nervous systems to calm or downregulate as we prepare to enter our online teaching environments: Consider the difference between offering ourselves a much-needed reprieve and resourcing our nervous systems through calming strategies. A reprieve activity is something we choose to do in service of avoiding, distracting, or procrastinating. Folks will sometimes attempt to find comfort in things like binge watching, social media, comfort foods, etc. None of these are inherently negative, however, they do little or nothing to resource us to better manage our stress in the long run. An example of how we might resource ourselves as we prepare for and teach synchronously is to take just one or two minutes before logging onto our online platforms to activate the calming or parasympathetic response in our bodies. Over time, the repeated action of intentionally calming or downregulating our nervous systems helps us to move into more of a default state of calm. If we are comfortable with focusing on our breathing, we might take just a few intentional, deep, and slow breaths in and out. We may try to gently extend our out-breath just a few seconds longer than the in-breath. This helps to activate the parasympathetic nervous system, which controls the body’s ability to relax. Click here for an online breathing tool. We may also activate the relaxation response by engaging through one or more of the senses we have available to us. We can stop for 30-60 seconds and listen to the sounds in our environments, or look around the room and bring attention to the different shapes and colours before us, or bring curious attention to our bodies and the points of contact as we sit, stand, or lie where we are. Each of the above activities invites us to tap into a greater state of presence, which often helps us to activate the calming response. We can choose a relaxation activity that is most comfortable for us.

Student Well-Being

Study after study has found a majority of university students report anxiety as one of their primary health concerns (e.g., American College Health Assessment, 2019). In fact, research on students from over 34 campuses across Canada has shown that 89% of Canadian college and university students experience high levels of psychological stress (Rashid & Di Genova, 2020). Aside from the rigours and expectations of their education programs, a number of adverse conditions have been found to contribute to these rising levels of stress and anxiety. These include a lack of critical resources, illness, childhood trauma, and/or ongoing experiences of interpersonal, systemic, and structural racism, discrimination, oppression, and injustice both within and beyond the education system itself. Not surprisingly, the pandemic has added additional stressors as most students have had to adjust to ongoing uncertainty, shifts in and out of remote learning, and a loss of support systems that previously buffered them from social isolation and disconnection. BIPOC communities have been disproportionately impacted in all aspects of the above, which has created further barriers to access, opportunity, and success.

Additionally, many students report experiences of stress and anxiety in response to being asked to engage in online dialogue, either synchronously or asynchronously. Most instructors would agree that dialogue is an essential tool in the classroom. However, research suggests that one in five speakers experience high levels of communication apprehension (Richmond et al., 2013). This apprehension can be influenced by a number of factors including introversion or shyness, and stress or anxiety. With an increase in online learning through platforms that offer opportunities for dialogue, speaking apprehension can be exacerbated by the inability to notice or respond to nonverbal cues, and so on (Rombalski, 2021). So, how do we create an online learning environment that engenders feelings of comfort and relative safety and promotes well-being?

As educators, we are uniquely positioned to be well-being advocates for students because of our regular contact with them. Many students will approach their instructors for advice and support before reaching out to formalized services, which is likely why instructors have increasingly voiced their need for guidance in this area. While specialized training and concrete resources offered by our institutions are crucial, there are ways to draw on student resilience and embed support through the implementation of our teaching work.

Research shows we can do this by enacting a pedagogy of care that prioritizes cultivating experiences of safety and inclusion within our classrooms. A culture of care is created when education systems and educators are responsive to students’ need for holistic well-being (e.g., academic, emotional, and social development) and when educators prioritize developing caring relationships with and amongst their students (Noddings, 1992). This whole person and restorative approach to education contributes to the conditions necessary for our students to learn, comfortably engage in online discussion, and thrive. Click here to watch educator Rita F. Pierson’s TED Talk about the importance of care.

Here are a few ways each of us can cultivate a culture of care within our online classroom environments:

Prioritize our own well-being: There are myriad downstream benefits for the classroom environment and student well-being when we prioritize our own. (Refer to Section 2: Instructor Well-Being).

Communicate and enact equity-minded pedagogy:

- Review the course syllabus for representation of contributions by BIPOC, people with disabilities, LGBTQ+, and other populations that have been historically excluded (i.e., readings, viewings, guest speakers). Click here for an example of a university syllabus review guide focused on equity.

- State how our positionalities influence our pedagogies. Understanding and acknowledging our own levels of power, rank, and privilege (racial, economic, social, ability etc.) and our understanding of the dynamics of systemic barriers help to create a climate of trust, connection, and inclusion.

- Create a diversity or inclusion policy to include within the syllabus.

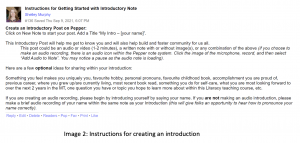

- Acknowledge and attune ourselves to the diverse identities, cultures, contexts, histories, backgrounds, abilities, and needs of students by inviting introductions before the course begins or within the first week (refer to example below). Share our introductions as a model. This gives us an opportunity to get to know our students better and build community with and amongst students from the outset (see Image 2).

Offer an introductory message to students that explicitly communicates your commitment to care: As education philosopher and care theorist Nell Noddings (2009) has argued, organizing education around themes of care, “does not work against intellectual development or academic achievement. On the contrary, it supplies a firm foundation for both” (p. 7). The following message, written during the time of the pandemic, comes from Social Work Professor, Dr. Gita Mehrotra:

Since we have varied levels of experience with online education, different levels of comfort with technology, diverse challenges related to the pandemic and beyond, and varied things going on in our personal lives at the moment, in this space, I ask us to practice self and community care. I ask us to meet each other with flexibility, grace, and compassion as we find our way forward. We will have glitches, we will likely change plans as the course goes on, and we will make mistakes. But, we will also show up, care for one another, read some cool stuff, ask ourselves hard questions about social work and social justice, do our best, and continue to learn and grow. I am committed to doing my best to support you. I care about you and your learning. We are in this together. (Mehrotra, 2021, p. 539)

Become familiar with markers of distress and how to respond: Particularly over the last few years of the pandemic, many of our students have experienced trauma, grief and overwhelm. Instructors play a central role in supporting student mental health because they are often in a direct position to be aware of changes or markers of student distress, or students reach out to us directly. While we may not be trained to offer counseling, we can play a critical role in helping students get the support they need. We can do this by reaching out to students in distress, offering a listening ear, and/or, when it’s called for, referring students to university mental health services.

Survey our students: By asking questions, we can gain a better understanding of their experiences and how to better support their academic and well-being needs. With just a few simple questions, we can gain important information about their lived experiences, strengths, challenges, and needs.

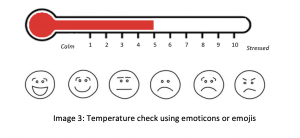

Begin each class with a check-in/temperature check: Particularly in online environments, students’ emotional experiences are not easily apparent to instructors – even with cameras on. As it turns out, they are not always apparent to the students themselves, either. By inviting students to pause and consider and share how they are feeling at the start of class, we send a signal of care and of valuing more holistic ways of knowing. Research also suggests that when we invite students to attune to their nervous systems and name what they are feeling, it helps to ease the stress response (Lieberman et al, 2007). Additionally, it gives instructors valuable information about what might be influencing students’ online classroom experience. A brief temperature check at the start of class can come in the form of inviting students to take 30 seconds or so to gauge and share their current emotional and/or physical state. Students may be invited to share a word or two in the chat (either publicly or privately), respond to a poll, or use emoticons or emojis (see Image 3). It turns out that the use of emoticons or emojis in online environments help to reduce transactional distance in virtual learning spaces by providing students with opportunities to feel a greater sense of interaction and psychological proximity with and from their instructors (Zhou & Landa, 2020). By inviting students to stop for a moment and orient themselves to their current mood or physical state, it also invites them to get out of the busyness of their worried minds. This invites a moment of mindfulness and a greater sense of ease as they transition into online discussion and learning.

Invite discussion through online dyads, triads, and small groups: Particularly in the midst of the pandemic, students have experienced rising levels of stress and anxiety that have resulted, in part, from social isolation and experiences of disconnection. This has a negative impact on attention, cognition and overall well-being. When we offer opportunities for collaboration, interaction, and small group discussion, this can help mitigate students’ experiences of stress and anxiety while also building community and connection. This, in turn, can help support thinking, reasoning, and wellness.

Incorporate movement breaks: Research conducted over the past 25 years has shown the positive impact of short, frequent movement breaks on positive affect, learning and student well-being (e.g., Donnelly & Lambourne, 2011; Rhoads et al., 2020). An effective movement break can come in the form of simply inviting students to stand for a moment and stretch, or through a brief guided movement practice. Inviting students to move and take a break from looking at their screens also provides a much-needed break for their eyes. Click here for three-minute guided movement break videos that can be incorporated in both synchronous and asynchronous learning environments.

Model calming or grounding strategies in class: Research shows that very brief mind-calming practices at the start of class improve the quality and depth of student learning and provide useful skills to help them cope with stress both in and outside of the classroom (Murphy, 2018). Additionally, when students are invited to tap into their parasympathetic nervous systems (a state often called rest and digest), they are more likely to feel at ease when engaging in both synchronous and asynchronous online discussion.

Examples of strategies:

- Arrive at least 10 minutes early to the virtual classroom. Consider playing a calming visual or sound for when the students arrive. Click here for online options (also refer to Create a Virtual Wellness Room below).

- Invite the students into very brief breathing or mindfulness activities. Keep in mind that we should have some general understanding of these practices before offering them to others (i.e., our own experiences of practising mindfulness and/or breath exercises). These practices should be offered in trauma-sensitive ways. For example, students should be invited into practice rather than compelled; students should have a choice in whether to have eyes opened or closed or cameras on or off during this time. It is important to note that not everyone is comfortable focusing on their breath. Click here for guided trauma-sensitive mindfulness practices recorded by the author.

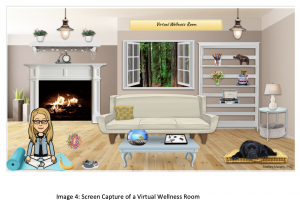

- Create or co-create a Virtual Wellness Room. A Virtual Wellness Room is designed to be an interactive experience through which we and our students can participate in brief calming or energizing activities. These activities can be done either synchronously or asynchronously. Each link embedded within an object within the Virtual Wellness Room leads directly to an on-the-spot tool, strategy, or activity for students to participate in. These approaches come in the form of online calming videos or audio recordings, breathing techniques, guided mindfulness practices, guided movements, calming art activities, and so on. I have created a template of a Virtual Wellness Room to explore, try out, and, if preferred, adapted to create a more personalized space. Click here for the template and click here to learn how to build a personalized Bitmoji. Alternatively, click here for instructions on how to create a Virtual Wellness Room from scratch. Image 4 shows an example of a Virtual Wellness Room.

Reflecting Back on the Scenario

As we will recall from our opening scenario, Kelly was interested in learning how to cultivate an online learning environment that could support her students’ mental health and wellness needs and be conducive to care, connection, meaningful dialogue and learning. Kelly was also interested in attending to her own well-being needs. Here are a few essential ideas that Kelly considered and implemented:

- As a start, Kelly began to focus on her own well-being. She learned that the most powerful strategy in her classroom is her commitment to her personal well-being practice. She recognized that her capacity to support her students’ well-being is limited by her own. Once she committed to focusing on her own well-being, there started to be a palpable ripple effect in the classroom. Additionally, by intentionally committing to her own well-being, she began to build the tools and skills necessary to better manage the inevitable stressors in her work life and beyond.

- Kelly surveyed her students at the beginning of her course and throughout to gauge their strengths as well as their academic and well-being experiences and needs (i.e., through surveys, polls, regular temperature checks and check-ins, etc.). This approach helped to co-create a culture of care and responsiveness.

- Kelly became familiar with resources offered through her university’s mental health services and became familiar with recognizing markers of distress in her students.

- Kelly committed to inviting students into brief calming practices and movement breaks at the start and/or middle of each class as a way to center a pedagogy of care, more holistic ways of knowing, and well-being.

- Kelly increased the number of opportunities for students to engage in dyad, triad, and small group discussions.

- Kelly co-constructed well-being support in the online classroom environment by enacting strategies that were responsive to her students’ interests, strengths, backgrounds, prior experiences, and needs.

By promoting and protecting our own well-being and by cultivating an online learning environment that honours and develops student wellbeing, we offer the conditions necessary to build a culture of care, to invite meaningful discussion, and support resilience and thriving in our classrooms and beyond. As bell hooks [sic] (1994) wrote, “To teach in a manner that respects and cares for the souls of our students is essential if we are to provide the necessary conditions where learning can most deeply and intimately begin” (hooks [sic], 1994).

References

American College Health Assessment. (2019). National College Health Assessment, Spring 2019: Executive Summary. https://www.acha.org/documents/ncha/NCHA-II_SPRING_2019_US_REFERENCE_GROUP_EXECUTIVE_SUMMARY.pdf

American Psychological Association. (2022, January 30). APA Dictionary of Psychology. https://dictionary.apa.org/stressor

Donnelly, J., & Lambourne, K. (2011). Classroom-based physical activity, cognition, and academic achievement. Preventive Medicine, 52(Suppl 1), S36–S42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2011.01.021

Harford, T. (2015, January 20). The Power of Saying “No.” TimHartford.com. https://timharford.com/2015/01/the-power-of-saying-no/

Hooks, b. (1994) Teaching to Transgress. New York: Routledge

Lieberman, M. D., Eisenberger, N. I., Crockett, M. J., Tom, S. M., Pfeifer, J. H., & Way, B. M. (2007). Putting Feelings Into Words. Psychological Science, 18(5), 421–428. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01916.x

Mehrotra, G. (2021). Centering a pedagogy of care in the pandemic. Qualitative Social Work, 20(1–2), 537–543. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473325020981079

Murphy, S. (2019). Fostering Mindfulness. Markham, ON: Pembroke.

Murphy, S. (2018). Preparing Teachers for the Classroom: Mindful Awareness Practice in Preservice Education Curriculum. In Byrnes, K., Dalton, J. & Dorman, B. (Eds.), Impacting Teaching and Learning: Contemplative Practices, Pedagogy, and Research in Education (pp. 41-51). Lanham, Maryland: Rowman and Littlefield.

Noddings, N. (2009). A Morally Defensible Mission for Schools in the 21st Century. Teachers College Press. (Reprinted from Clinchy, Evans, ed. Transforming Public Education: A New Course for America’s Future. (New York: Teachers College Press, 1997, pp. 27-37). https://jotamac.typepad.com/files/a-morally-defensible…noddings.pdf

Noddings, N. (1992). The challenge to care in schools: An alternative approach to education. Teachers College Press.

Rashid, T., & Di Genova, L. (2020). Campus mental health in times of COVID-19 pandemic: Data-informed challenges and opportunities. Campus Mental Health: Community of Practice (CoP), Canadian Association of Colleges and University Student Services. https://campusmentalhealth.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Campus-MH-in-Times-of-COVID-19_Rashid_Di-Genova_Final.pdf

Rhoads, M. C., Kirkland, R., Baker, C. A., Yeats, J. T., & Grevstad, N. (2020). Benefits of movement-integrated learning activities in statistics and research methods courses. Teaching of Psychology, 48, 197–203. doi:10.1177/0098628320977265

Richmond, V. P., Wrench, J. S., & McCroskey, J. C. (2013). Communication apprehension, avoidance, and effectiveness. Pearson.

Rombalski, B. (2021). Communication apprehension: A pressing matter for students, a project addressing unique needs using communication in the discipline Workshops [Doctoral dissertation, California State University]. Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations, 1304. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd/1304

Zhou, S., & Landa, N. (2021, July 5-8). Using emoticons to reduce transactional distance in virtual learning during the COVID-19 crisis [Conference presentation]. Fifteenth General Conference: The Future of African Higher Education, East Legon, Accra, Ghana. https://event- mgt.aau.org/event/50/contributions/84/contribution.pdf