Blueprinting Technology-Enhanced Learner Experiences

L O'Neill

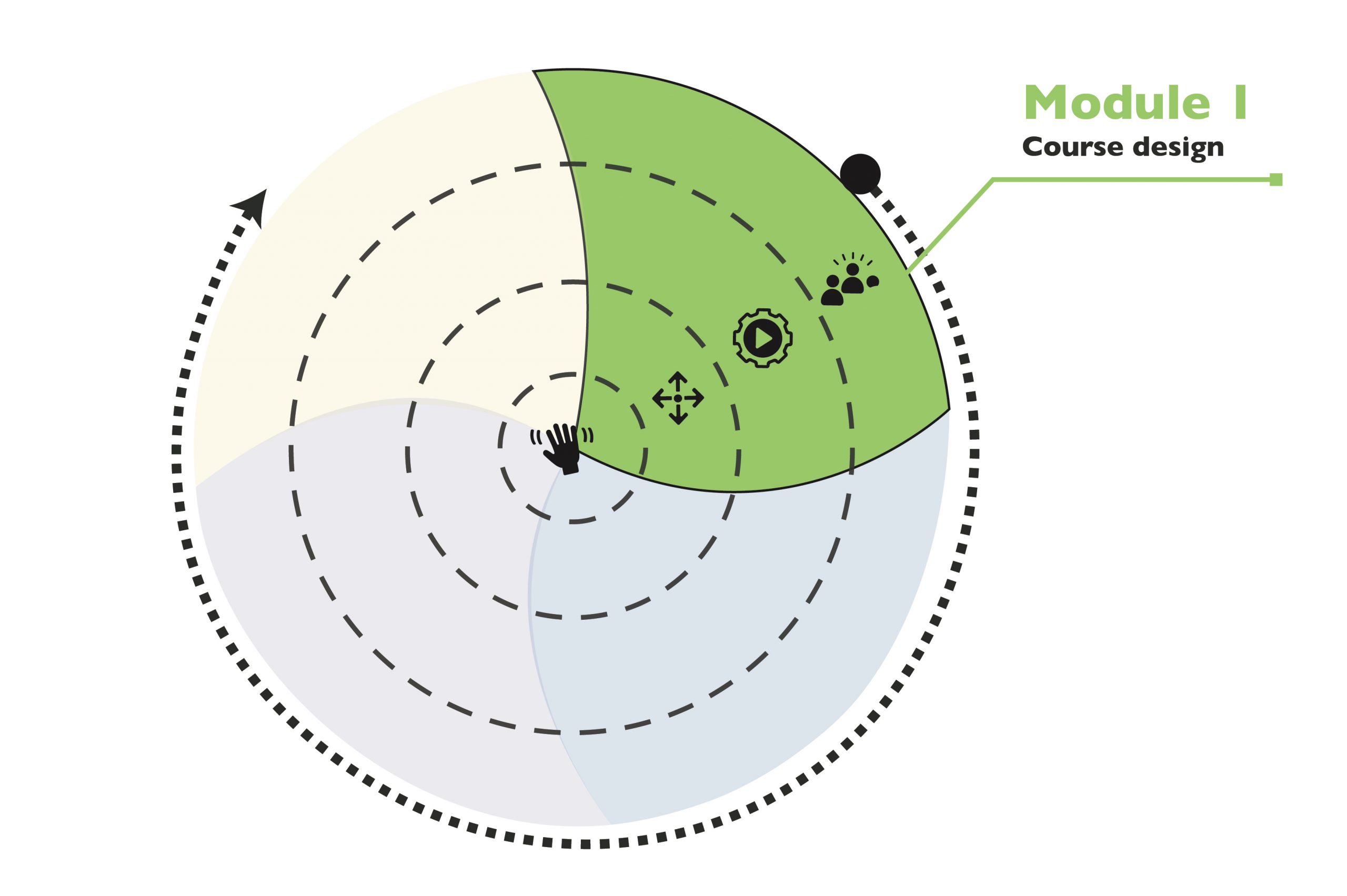

In this module, you will create and refine a draft blueprint for your course/workshop.

|

Key Takeaways Draft a thoughtful course design that will map the build of your online course space. Design opportunities in your course to give and get formal and informal feedback. |

This module has 4 parts:

Introduction![]()

Identifying the ‘location’ of this module within the course level learning will spark the introduction of module theories being considered (connectivism and flow). These process of design blueprinting is introduced at this point also. As a first method of working with these, in context, a template will be provided.

![]()

Expansion

A worked example is provided to show a blank versus a roughed in blueprint template for a post-secondary course. The concept of ‘flow’ is presented for consideration.

![]() Refinement/Application

Refinement/Application

Participants are asked to return to first drafts, to refine designs. Benefits and challenges are presented to close this phase.

![]() Reflective Practice

Reflective Practice

With a focus on flow approaches, participants are asked reflective questions about their own process/decisions in the design and adaptation activities presented.

Introduction

Introduction

| Download Video file | Download transcripts | Download slides |

![]() When choosing to incorporate technology-enabled spaces in teaching, it’s far too easy to return to learning experiences where learners

When choosing to incorporate technology-enabled spaces in teaching, it’s far too easy to return to learning experiences where learners

passively consume our course curriculum like one might binge-watch the latest season of [insert your favorite show here].

A learner-centred perspective on instruction presents knowledge management with its central challenge since “circulating human knowledge is not simply about search and retrieval” (Brown & Duguid, 2002, p. 124). The harvesting of information and intellectual capital are important to knowledge management but are “subordinate to the matter of learning for it is learning that makes intellectual property, capital, and assets usable” (Brown & Duguid, 2002, p. 124).

This unit supports the design of engaging blended and online learner experiences by aligning our designs to the ways people learn in activity and through technology. The first and overarching theory introduced in this unit is constructivism. Constructivism most importantly recognizes that learners are not passive recipients of knowledge but those who ‘construct’ knowledge.

In support of constructivism our second theory, connectivism, assists us in designing technology-enabled spaces, as it supports the distribution of knowledge across networks. Learners then traverse those networks to make connections. A connected perspective on learning which supports authentic learning is the idea that people enter a state of flow when learning. Because flow views learning as a process, it further supports the co-construction of knowledge, situated in contexts, embedded within environments (both physical and virtual)… but more about that later.

A constructivist primer

Constructivism and Social Constructivism are two similar learning theories that share a large number of underlying assumptions, and an interpretive research ‘position’.

Both approaches

- Deep roots in classical antiquity. Socrates, in dialogue with his followers, asked directed questions that led his students to realize for themselves the gaps in their thinking.

- Learning is perceived as an active, not a passive, process, where knowledge is constructed, not acquired.

- Knowledge construction is based on personal experiences and the continual testing of hypotheses.

- Each person has a different interpretation of’ and process for’ constructing knowledge based on past experiences and cultural factors.

Social Constructivism

- Emphasizes the collaborative nature of learning and the importance of cultural and social context.

- All cognitive functions are believed to originate in, and are explained as, products of social interactions.

- Learning is more than the assimilation of new knowledge by learners; it is the process by which learners are integrated into a knowledge community.

- Believes that individual constructivism overlooked the essentially social nature of language and so supports learning as a collaborative process.

Underlying Assumptions

Jonassen (1994) proposed that there are eight characteristics that underline the constructivist learning environments and are applicable to both perspectives:

- Constructivist learning environments provide multiple representations of reality.

- Multiple representations avoid oversimplification and represent the complexity of the real world.

- Constructivist learning environments emphasize knowledge construction instead of knowledge reproduction.

- Constructivist learning environments emphasize authentic tasks in a meaningful context rather than abstract instruction out of context.

- Constructivist learning environments provide learning environments such as real-world settings or case-based learning instead of predetermined sequences of instruction.

- Constructivist learning environments encourage thoughtful reflection on experience.

- Constructivist learning environments “enable context- and content- dependent knowledge construction.”

- Constructivist learning environments support “collaborative construction of knowledge through social negotiation, not competition among learners for recognition.

Becoming a Better University Teacher by UCD Teaching and Learning is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License.

A connectivist primer (… think distributed learning)

A network can be defined as connections between ‘things’. Computer networks, power grids, and social networks all function on simple principles that nodes (people, groups, systems, entities, etc.) can be connected to create a new ‘thing’. Altering elements of a network has a ripple effect on the whole, and nodes that increase their profile (through interaction with other nodes, by performing actions, etc.) will be more successful at acquiring additional connections and expanding further.

Applied to the context of learning, the likelihood that two concepts of learning can be linked depends on how well each is currently linked. Nodes can be fields, ideas, or communities that specialize and gain recognition for their expertise, have greater chances of recognition, thus resulting in cross-pollination of learning communities. Weak ties are links or bridges that allow short lived connections between information. Our small world networks are generally populated with people whose interests and knowledge are similar to ours. Finding a new job, as an example, often occurs through weak ties.

Underlying assumptions

Learning is a process that occurs within nebulous environments of shifting core elements – not entirely under the control of the individual. Learning (defined as actionable knowledge) can reside outside of ourselves (within an organization or a database), is focused on connecting specialized information sets, and the connections that enable us to learn more are more important than our current state of knowing.

Connectivism is driven by the understanding that decisions are based on rapidly altering foundations. New information is continually being acquired. The ability to draw distinctions between important and unimportant information is vital and critical to support. The ability to recognize when new information alters the landscape based on decisions made yesterday is also critical.

Principles

- Learning and knowledge rests in diversity of opinions;

- Learning is a process of connecting specialized nodes or information sources;

- Learning may reside in non-human appliances;

- Capacity to know more is more critical than what is currently known;

- Nurturing and maintaining connections is needed to facilitate continual learning;

- Ability to see connections between fields, ideas, and concepts is a core skill;

- Currency (accurate, up-to-date knowledge) is the intent of all connectivist learning activities; and

- Decision-making is itself a learning process. Choosing what to learn and the meaning of incoming information is seen through the lens of a shifting reality. While there is a right answer now, it may be wrong tomorrow due to alterations in the information climate affecting the decision.

Creating, preserving, and utilizing information flow should be a key organizational activity. Knowledge flow can be likened to a river that meanders through the ecology of an organization. In certain areas, the river pools and in other areas it ebbs. The health of any learning ecology depends on effective nurturing of information flow.

The starting point of connectivism is the individual. Personal knowledge is comprised of a network, which feeds into institutions, which in turn feeds back into the network, and then continues to provide learning to individuals. This cycle of knowledge development (personal -> network -> organization) allows learners to remain current in their field through the connections they have formed.

‘Connectivism: A learning theory for the digital age‘ by George Siemens is licensed under CC BY 4.0

John Seely Brown (2010) presents an interesting notion that the Internet leverages the small efforts of many with the large efforts of few. The central premise is that connections created with previously unconnected nodes supports and intensifies existing large effort activities. Brown provides the example of a Community College project that linked senior citizens with elementary school students in a mentorship program. The children “listen to these ‘grandparents’ better than they do their own parents, the mentoring really helps the teachers” – the seniors (small efforts of the many) – complement the teachers (large efforts of the few). This amplification of learning, knowledge, and understanding is accomplished by extending personal networks, and so is at the core of connectivism.

Application

Application

| Download Video file | Download transcripts | Download slides |

First things first: download a design blueprint template.

Starting in this module, you will create a draft design for your own module/workshop/course. We will return to your draft design throughout this course to help you refine your design based on new information introduced, and activities completed in Module 2, 3, and 4!

I’ve created and shared, below, an example of a completed design (based on how I have designed this module) for you! If you want to read details, in the upper right corner, you can ‘make fullscreen’.

Expansion

Expansion

A FLOW primer

The 9 dimensions of FLOW; from a learner’s perspective

| Balance between the degree of challenge and the current skill level (a learner feels engaged by the challenge, but not overwhelmed) | Action and awareness are merged without distracting thoughts (a learner feels completely immersed in the task at hand) | It is very clear what should occupy our attention (a learner has a good grasp of what to do next) |

| Reactions are adjusted to meet current demands due to timely feedback (a learner knows how well they are doing, all the time) | Absorbed in the activity, we are aware of what is task relevant (a learner has a high level of concentration) | An absolute sense of personal control (a learner is able to do what they feel is right) |

| Lack awareness of being self-conscious (a learner loses their need to protect their ego) | Time either slows down or flies by (a learner feels engaged ‘in the moment’) | An activity is done for its own sake (a learner feels ‘value’ in the activity regardless of reward system) |

As you can see from the table above, instructors must balance the complexity of quality learning experiences with the design of teaching. The Design Blueprint helps you to draft a flow of a module/week/course. Note in the table above that principles of flow assume the presence of ‘feedback loops’ (e.g., “a learner knows how well they are doing’). There are technology features that can automate this feedback loop but, for now, let’s say that you are in charge of this. Where in the chosen individual or group activity can you intervene to confirm that this is true? What might you say or do to achieve this? Is it noted in your design blueprint yet? Add this notation now while you are thinking about it.

Refining your draft to account for flow

The template provided will be used throughout this course in order to help you to embed practices which are known to create quality tech-enabled learning experiences. How will you refine your draft as a whole, in order to embed the dimensions of FLOW that benefit you and your learners in instruction, in activity, and/or in assessment?

Reflective practice

Reflective practice

This module allowed you space and a foundation to draft a design blueprint for your course/workshop. Further detail asked that you look back to your draft and refine it (where relevant) to support Flow.

What changes have you made to your draft, and why did you make these choices?

Save your refined map as a PDF by going to your ‘file’ pulldown menu, choosing ‘export’ and selecting PDF. Grab a colored pen and annotate areas of your draft design that support principles of Flow. Add detail to your annotation that state why this change was made.

Module References

Brown, J. S., & Duguid, S. (2000). The social life of information. Harvard Business School Press.

Hagel III, J., Brown, J. S., and Davison, L. (2010). The power of pull: How small moves, smartly made, can set big things in motion. Basic Books.

Herrington, J., & Oliver, R. (2000). An instructional design framework for authentic learning environments. Educational Technology Research and Development, 48(3), 23-48. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02319856

Rowe, K. (2006). Effective teaching practices for students with and without learning difficulties: Constructivism as a legitimate theory of learning AND of teaching? Australian Council for Educational Research: Student learning processes series. https://research.acer.edu.au/learning_processes/10

Vygotsky, L. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press.

Go Beyond the Module with These Readings and Resources

- A bit more about the Power of Pull with John Seely Brown

- Eight Tips for Fostering Flow in the Classroom. Greater Good magazine

constructivist learning is active, not passive; constructed, not innate; and personally experienced by each individual learner

Connectivism is the integration of principles explored by chaos, network, and complexity and self-organization theories.

A state of flow is very similar to what people mean when they say they are 'in the zone'. It is a state of immersion in learning and experience.